Not everyone has eye-popping deductibles: How one union kept medical bills in check

BOSTON — Even as soaring insurance deductibles wreak financial havoc on millions of American families, some workers have managed to dodge the affordability crisis.

In Boston, a labor union representing the city’s hotel workers offers its members health coverage with no deductible and family premiums just a tenth of the U.S. average.

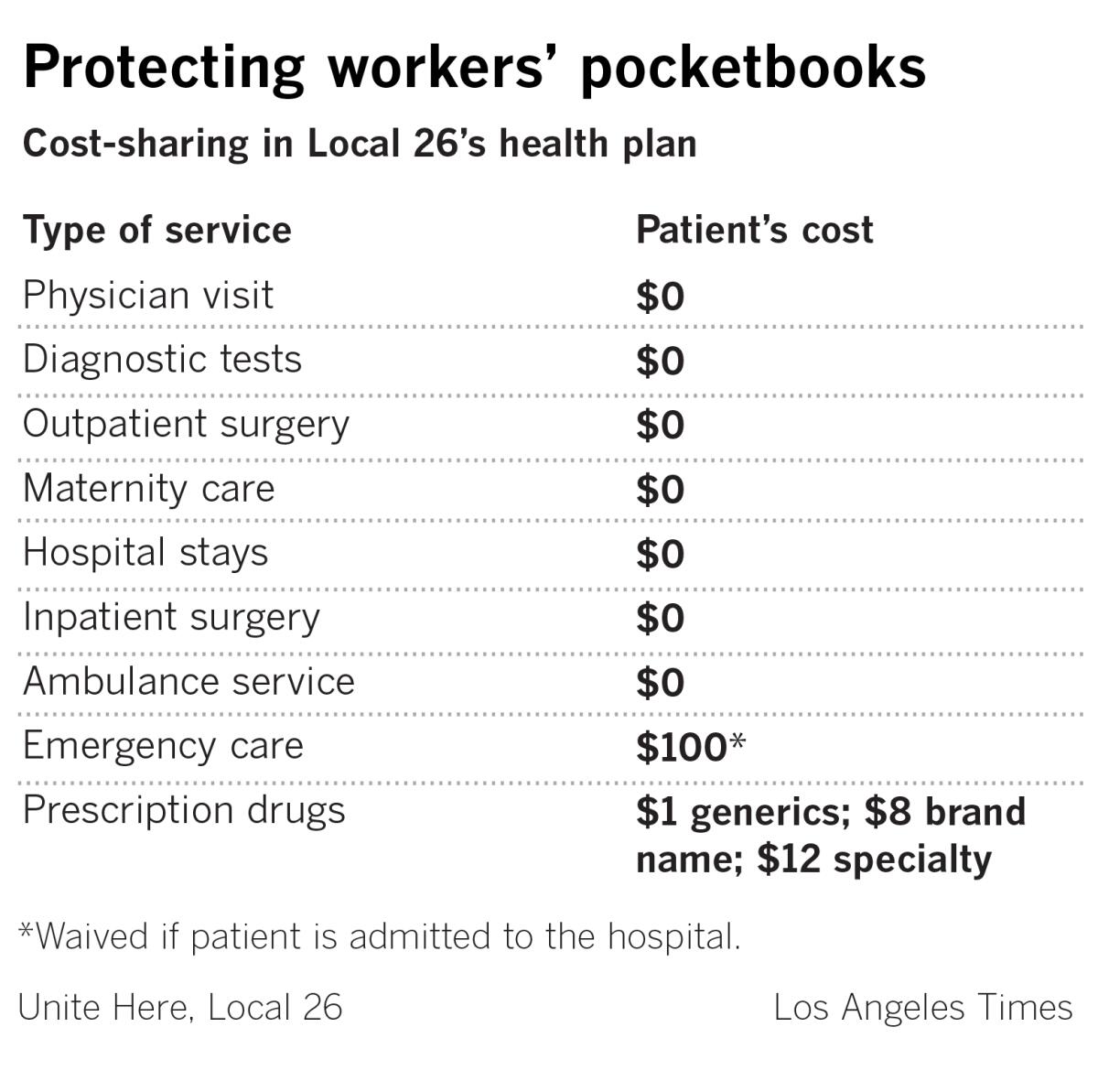

Workers and their families pay nothing out-of-pocket for doctor visits, tests and hospital stays. Even the most expensive specialty drugs cost just $12 per prescription. Generics are $1.

The push by Unite Here, Local 26, to protect Boston hotel workers highlighted the challenges of protecting patients from medical bills, as workers were forced to make difficult choices. But the union’s success — in one of the most expensive healthcare markets in the country — also suggests that Americans may not have to settle for huge deductibles that have put medical care out of reach for millions.

“Everyone says we can’t do anything about costs, or we just have to get patients to put more ‘skin in the game,’” said John Brouder, a longtime health benefits consultant who worked with Local 26 to develop its health plan. “This union showed that’s not true.... It’s a very profound and important message.”

Delivering that peace of mind wasn’t easy. Starting in 2013, when the new health plan debuted, Local 26, which provides coverage for roughly 9,000 union members and their families, had to confront the biggest cause of soaring insurance premiums and deductibles: the high price of U.S. medical care, particularly at hospitals.

It required union members to make a trade-off that many, at first, found unpalatable — giving up access to some of the city’s best known, and most expensive, hospitals.

In return, however, workers not only kept their insurance premiums under control, they saved so much money that housekeepers like Rajae Nouira saw their hourly pay increase from $16.98 to $23.60 in five years, a 39% jump.

Over the same time period, hourly wages for all U.S. workers increased by less than 15%, according to federal data.

“This insurance has been a godsend,” said Nouira, who works at a downtown hotel. Nouira, who is 40, spent much of the summer juggling her job with frequent trips to the obstetrician and the hospital as she navigated her fourth — and most complicated — pregnancy. Unlike most American workers, though, she didn’t have to worry about medical bills.

Six years after implementing the plan, the union is still paying less in medical costs per member than it was in 2013, even while healthcare costs nationally have steadily increased faster than overall inflation.

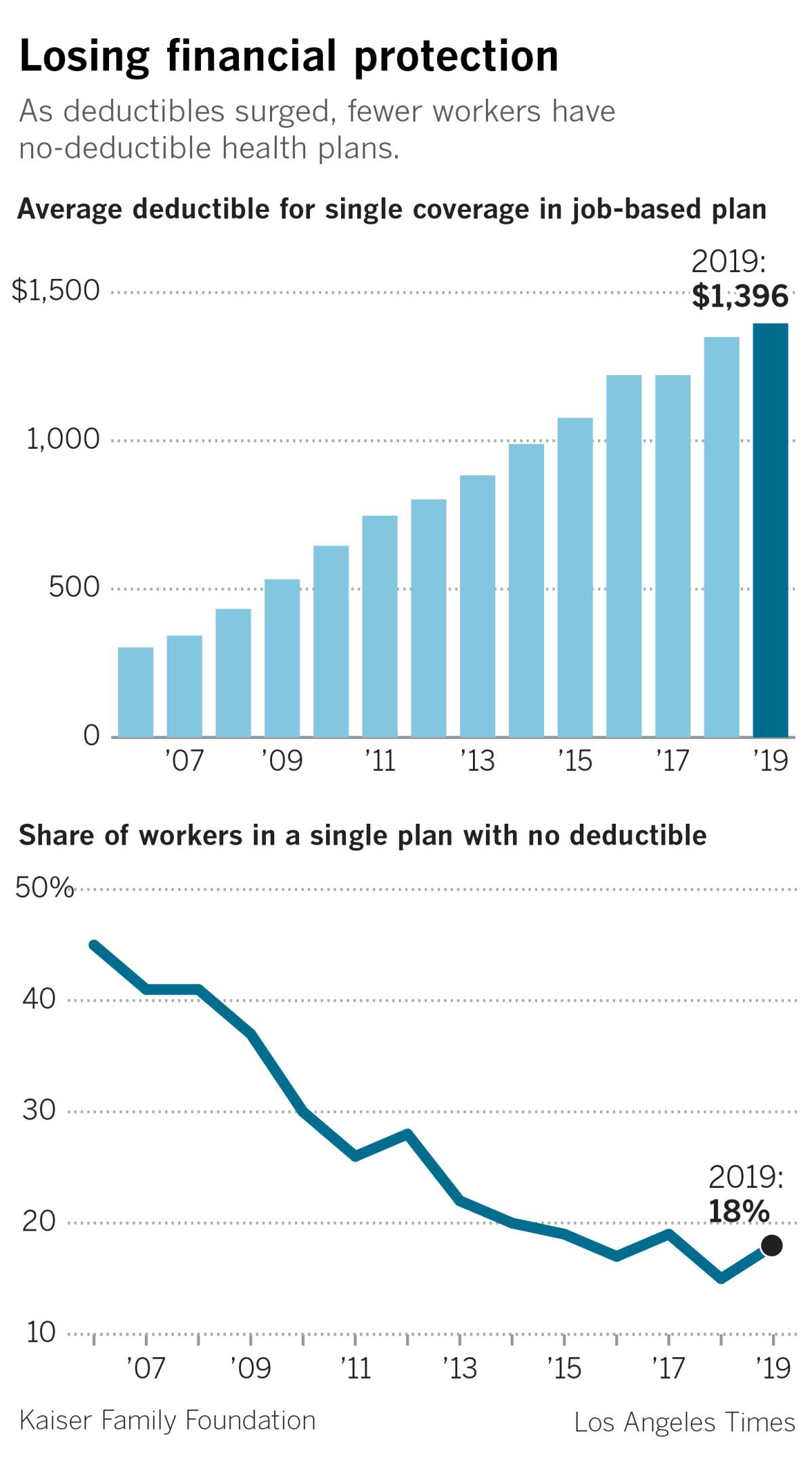

Over the last decade, employers have systematically shifted healthcare costs onto employees, requiring workers to pay higher premiums and pushing the average deductible on a single job-based plan to almost $1,400, nearly three times what it was a decade ago.

The run-up has saddled Americans with medical bills they can’t afford, even with insurance, a Times examination of job-based coverage found.

Half of U.S. workers with job-based coverage say they or a close family member have delayed care in the last year because of cost, according to a nationwide poll conducted for this project in conjunction with the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.

Seven years ago, the leaders of Local 26 feared their members were destined for the same fate.

The union, which traces its roots to the late 19th century when bartenders in the city voted to organize, was facing a crisis.

Local 26, like many unions, had long offered members a health plan, which was largely funded by the hotels that employed its members. Such Taft-Hartley plans, as they are called, are prized by unions, as they typically offer good benefits and have preserved workers’ health protections, even when wages have stagnated.

But Local 26’s plan had a history of struggling, as rising medical costs sapped the plan’s reserves and jeopardized coverage for workers and their families, many of whom are immigrants from Latin America, Africa and East Asia.

Several times, the plan nearly went bankrupt.

In 2003, confronted by one financial crisis, the plan experimented with deductibles, though union leaders pulled them back when the crisis passed. A few years later, with another crisis upon them, members had to give up a 25-cent-an-hour wage increase to prop up the plan.

“We had to do something to change this cycle,” said Brian Lang, a pugnacious former meatpacker who took over leadership of Local 26 in 2011. “I didn’t know what it would be, but I knew it had to be big.”

As union leaders began digging into the medical bills the plan was paying, the problem became starkly clear: The Local 26 health plan — like most health insurance plans across the country — was being crushed by skyrocketing prices for hospitals and other medical services.

Between 2013 and 2017, the average price nationally for an inpatient hospital admission rose more than 15%, almost three times the rate of general inflation, according to an analysis of commercial insurance data by the Health Care Cost Institute, a Washington think tank. The average price for outpatient services jumped almost 19%.

In some metropolitan areas, inpatient hospital prices increased by more than 30% in just five years.

“Price is the elephant in the room,” said Niall Brennan, the institute’s president. “People don’t like to talk about it … but patients in many places are being subjected to basically predatory pricing practices.”

The price problem has been most acute in communities with dominant hospital systems, studies show.

In California, for example, hospitals that were part of Sutter Health and Dignity Health, the state’s largest hospital systems, increased prices almost 50% faster than other hospitals in the state between 2004 and 2013, researchers found.

“Everybody knows that when you go to the airport, a $2 bottle of water is $8 because there is no competition,” said Glenn Melnick, a health economist at the University of Southern California. “Consumers pay the higher price because they have no choice. The same thing is happening in healthcare.”

In Boston, the 1994 merger of two of the city’s premier academic medical centers — Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital — created a powerhouse known as Partners HealthCare with unparalleled ability to demand high prices.

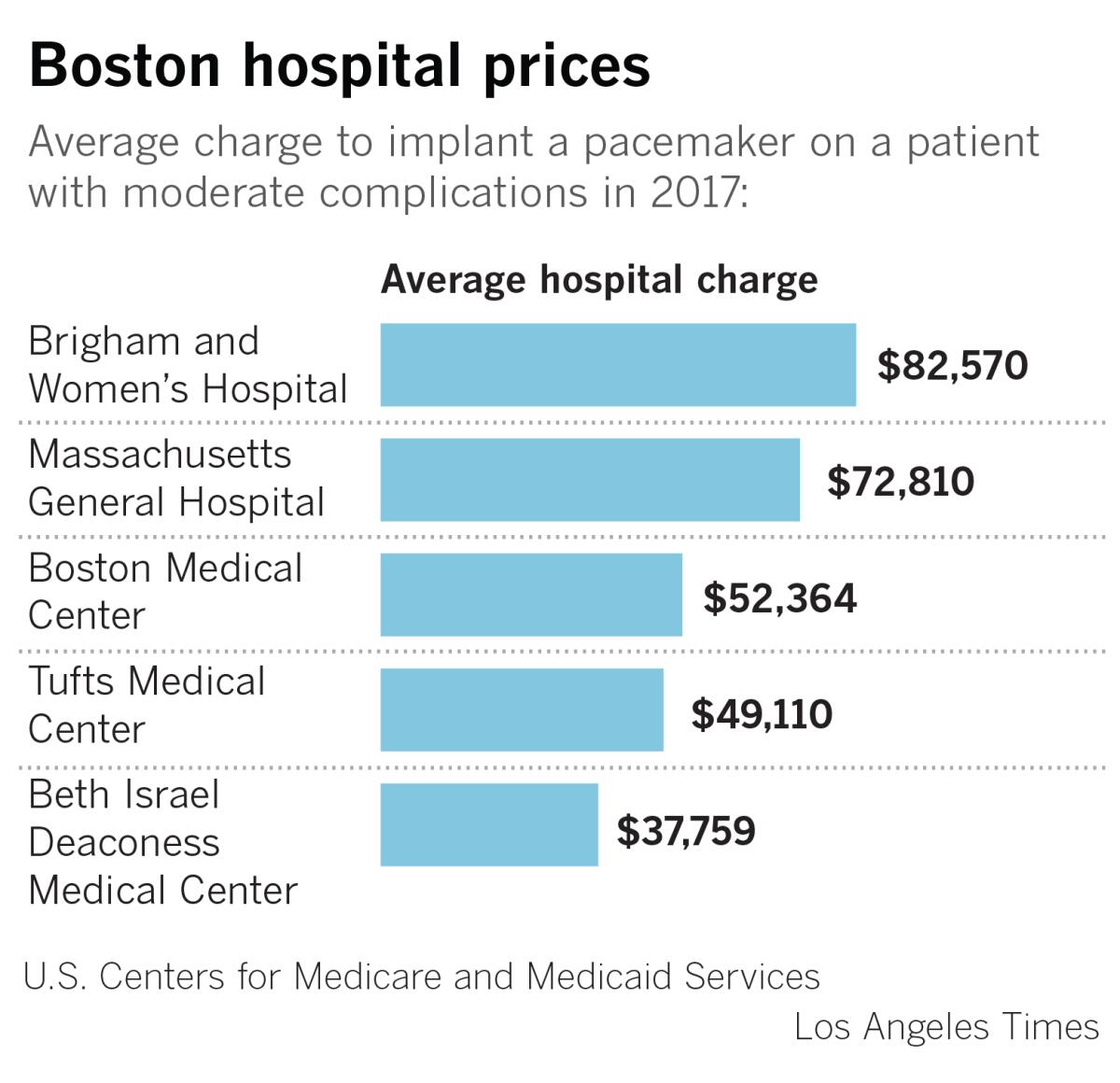

When Local 26 officials began their research, they were stunned to see that the Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s charged two or in some cases even three times as much as other academic medical centers in Boston.

For example, a hip replacement at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center — which, like Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s is a teaching hospital for Harvard Medical School — cost $28,359, according to federal data.

Massachusetts General charged $55,362 for the same procedure, and Brigham and Women’s charged $65,073.

“I resented what Partners was doing,” Lang said. “I thought, ‘This is such a rip-off. They are taking our money.’”

Hospital charges represent the list price for a procedure, which is typically higher than the price insurers negotiate with hospitals. Nevertheless, the charges illustrate price disparities.

Partners, which has been under pressure in Massachusetts for years to moderate its prices, declined to comment for this story.

Confronting these prices, union leaders and officials from Tufts Health Plan, which administers Local 26’s insurance, urgently searched for new ways to keep their plan afloat.

From the start, the union ruled out high deductibles. “They were very clear that they wanted to reduce costs, but not by shifting costs onto their members,” recalled Marisa Fusco, a Tufts official who works with the union.

“We had this idea that if we could put more money in our members’ pockets, that would do more for their overall health than anything we could do in the health plan,” explained Joey Mokos, a senior official at Unite Here Health, which helped develop the plan.

That put the focus on the high costs of Boston’s most expensive hospitals.

Mokos, Lang and other union officials knew telling workers they could no longer go to world-renowned medical centers like Massachusetts General or Boston Children’s would be difficult, even if equally high-quality options existed.

So, Local 26 put the question to a vote: Should members get a narrower network of medical providers and guaranteed wage hikes? Or should they keep access to all Boston hospitals, but give up raises for 2 ½ years to keep the health plan from going bankrupt?

It was a bruising campaign.

Many union members fiercely resisted having to give up care at places they knew, recalled Ingrid Almonte, a housekeeper at one of Boston’s big hotels.

“Every day, we would try to tell them it was our money, and we should keep it,” she said.

Seven candidates qualified for Thursday’s Democratic presidential debate in L.A. Here’s where they stand on Medicare for all, abortion, the opioid crisis.

In the end, two-thirds of the membership backed the switch to the new, limited network plan.

It rolled out in late 2013. Workers got a raise the next year.

Around the country, most employers have been reluctant to try to control costs by restricting where workers can seek medical care. Many recall the backlash against HMOs in the 1990s.

Just 2% of employers have eliminated hospitals or health systems from their insurance networks, as Local 26 did, according to a nationwide employer survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Employers, particularly large ones such as Walmart, have shown more interest in what is called tiering. Tiered plans offer workers a discount to seek care at lower priced or more efficient hospitals.

But this strategy also remains rare, in part because most companies don’t have the resources to design a health plan that sets prices based on the quality and value of individual hospitals and doctors.

Sensitive to the bruised feelings of workers who opposed the more limited network, Local 26 focused on showing members that the new plan would have benefits besides just lower overall health costs.

Because Local 26 controlled the health plan, the union was able to translate healthcare savings into higher wages. And when union leaders rolled out the plan, they mounted an intense campaign to connect workers with primary care physicians to help manage their care.

The union estimated it reached more than 95% of the 4,000 or so members at open enrollment.

The effort paid off almost immediately, as workers’ use of high-cost emergency rooms at Boston hospitals dropped significantly in the first year.

Six years later, insurance premiums remain in check. This year, workers pay just $16 a month for a single plan and $48 a month for a family plan.

By contrast, the average job-based health plan nationally required workers to pay $104 a month for a single plan and $501 a month for a family plan, according to the latest Kaiser Family Foundation survey.

For the Boston hotel workers, the payoff has been even greater, as the steady wage increases have helped fill rainy-day funds, save money for college and buy homes.

Nouira and her family, who had been squeezed into a small apartment, used the extra money from her raises to get a modest house in a working class suburb north of Boston.

“Try living in an apartment with three kids,” she joked. “It wasn’t much fun.”

Nouira’s three-bedroom home backs up on a commuter line, and she and her husband, who is an accountant, rent out the downstairs to help pay the mortgage.

But the children now have a small backyard where they can play. There is even a swimming pool.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.