Health insurance deductibles soar, leaving Americans with unaffordable bills

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

Reporting from Washington — Soaring deductibles and medical bills are pushing millions of American families to the breaking point, fueling an affordability crisis that is pulling in middle-class households with health insurance as well as the poor and uninsured.

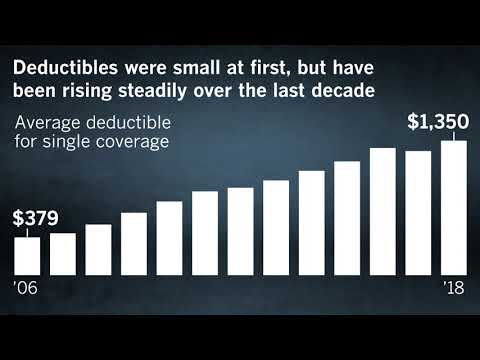

In the last 12 years, annual deductibles in job-based health plans have nearly quadrupled and now average more than $1,300.

Yet Americans’ savings are not keeping pace, data show. And more than four in 10 workers enrolled in a high-deductible plan report they don’t have enough savings to cover the deductible.

One in six Americans who get insurance through their jobs say they’ve had to make “difficult sacrifices” to pay for healthcare in the last year, including cutting back on food, moving in with friends or family, or taking extra jobs. And one in five say healthcare costs have eaten up all or most of their savings.

Those are among the key findings of a Los Angeles Times examination of job-based health insurance — the most common form of coverage for working-age Americans — which has undergone a rapid transformation, requiring patients to pay thousands of dollars out of their own pockets.

The conclusions are based in part on a nationwide poll The Times conducted in partnership with the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation, or KFF. Two Washington-based think tanks — the Health Care Cost Institute and the Employee Benefit Research Institute — provided supplemental analysis.

How the L.A. Times/Kaiser Family Foundation poll was conducted »

The Times also interviewed doctors, business leaders, researchers and dozens of Americans with high-deductible coverage and reviewed scores of studies and surveys of health insurance in the U.S.

At a time when healthcare is poised to be a central issue in the 2020 presidential election, these sources provide a comprehensive look at changes that have profoundly reshaped insurance.

The explosion in cost-sharing is endangering patients’ health as millions, including those with serious illnesses, skip care, independent research and the Times/KFF poll show.

The shift in costs has also driven growing numbers of Americans with health coverage to charities and crowd-funding sites like GoFundMe in order to defray costs.

And it is feeding resentments and deepening inequalities, as healthier and wealthier Americans are able to save for unexpected medical bills while the less fortunate struggle to balance costly care with other necessities.

“It feels like the system isn’t working,” said Andrew Holko, a 45-year-old father of two who is facing $5,000 in outstanding medical bills because of diabetes medications, cortisone injections his wife needs for pelvic pain, a recent trip to the emergency room for his 9-year-old daughter and other services.

Holko’s information technology job puts his household income above $80,000, close to the median for a family of four. But with a mortgage, student loans and two growing children, Holko says he has little extra to cover a $4,000 annual deductible.

“We shop at discount grocery stores. My wife is couponing. We are putting every single bill we can on the credit card,” Holko said, noting that even a family meal at McDonald’s seems like a luxury. “We’re drowning.”

In the poll of working-age adults with job-based insurance, a quarter said they had put off vacations or major purchases in order to pay for healthcare. A quarter have curtailed spending on clothing and other basic household goods.

Half said costs had forced them or a close family member to delay a doctor’s appointment, not fill a prescription or postpone some other medical care in the previous year. That is higher than some other national surveys, but a study published Thursday by American Cancer Society researchers found that in the last year, 56% of all U.S. adults had problems paying medical bills, delayed care or worried about affording care.

Hardest hit in the cost shift are lower-income workers and those with serious medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer — who are more than twice as likely as healthier workers, according to the Times/KFF poll, to report problems paying medical bills and to say they’ve cut back on spending for food, clothing and other household items.

“There has been a quiet revolution in what health insurance means in this country,” said Drew Altman, the longtime head of the Kaiser Family Foundation. “This happened under the radar while everyone was focused on the Affordable Care Act.”

The 2010 healthcare law — often called Obamacare — provided landmark protections to Americans once shut out of health coverage. But as Democrats and Republicans fought over the law, Altman said, neither focused on the rapid run-up in costs for people covered through work.

Are you facing high medical costs because of a high-deductible health plan? Tell us your story »

“We forgot that most people get their insurance through an employer, and for them, the issue is medical bills that they increasingly cannot afford,” Altman said.

As recently as 2006, nearly half of workers had a health plan with no deductible at all: Their insurance began immediately covering medical costs, often requiring them to pay, at most, a small percentage of their bills.

The average deductible for a single worker with a job-based insurance plan in 2006 was just $379, adjusted for inflation, according to an annual employer survey that KFF has conducted for more than two decades. By 2018, that figure had more than tripled to $1,350. Four in 10 U.S. workers have at least a $1,500 deductible — the threshold the poll used for high-deductible coverage for individuals.

Over the same time, insurance premiums also increased, rising at more than double the rate of inflation and outpacing wage gains.

“People are trying hard to do the right thing, but care is being priced out of their reach,” said Dr. Barbara McAneny, president of the American Medical Assn., the nation’s largest physicians’ organization.

Like many doctors, nurses and hospital leaders, McAneny, an oncologist in New Mexico, can tick off stories of patients who have health insurance yet delayed critical care, fearing the bills.

“The original idea of deductibles and co-pays theoretically might have made sense — if patients have more responsibility for how they spend medical dollars, they would be more careful,” McAneny said. “But it is just shifting costs to the patients, and people are forgoing care they need.”

Feeling the strain are people like Sandy Westbrook, a 55-year-old nurse’s assistant at an Ohio nursing home.

Westbrook, who earns less than $12 an hour, says she cut back on trips to the grocery store as she scrimped to pay off nearly $1,000 in medical bills after she broke her wrist and had to see a cardiologist for stress. “I get fed at work, thank God,” she said.

Shanona Nichols, a 26-year-old office assistant in Michigan, moved back in with her mother to save money to pay medical bills from treatment for endometriosis.

Tomas Krusliak, a 27-year-old chef in western Virginia, took on two extra jobs, working some days from 5 a.m. to 11 p.m., to pay medical bills after his wife had a miscarriage as the couple tried to have their first baby. They had a $5,000 deductible.

“I was used to having insurance where I could go to the doctor and get the treatment I needed,” said Krusliak, who is originally from Slovakia. “It was definitely a shock when I got to the U.S. and learned that even when you are working and getting insurance, you have to spend even more money to get treatment.”

Many other industrialized nations rely on private health insurance, but few of their citizens face the kind of medical bills Americans routinely do. Fewer than one in 10 patients in Germany and Holland, for example, reported problems getting medical care because of cost, the New York-based Commonwealth Fund found in a 2016 survey.

By contrast, four in 10 U.S. workers had difficulty paying a medical bill or insurance premium in the previous 12 months, according to the Times-KFF poll conducted last fall.

The challenges are most severe for people with the highest deductibles, according to the poll: Nearly half of those in a plan with at least a $3,000 individual deductible or a $5,000 family deductible reported problems affording healthcare.

Even Americans with chronic conditions such as diabetes use less medical care if they have a high-deductible plan, according to an analysis conducted for The Times by the Health Care Cost Institute, which examined three years of insurance data for 10 million workers.

Other academic studies show patients with cancer, epilepsy, arthritis, multiple sclerosis and other serious diseases also delay care or skimp on vital medications when they are required to pay more out of pocket. Doctors typically recommend patients with such conditions get regular care to control the disease and prevent complications.

This wasn’t how the high-deductible revolution was supposed to play out.

Twenty years ago, amid a backlash against HMO restrictions on people’s ability to choose their doctors, high-deductible plans were billed as a way to empower patients and free them from the unpopular constraints of managed care.

Healthcare costs have been an issue for decades. Deductibles were meant to give patients skin in the game, but have risen steadily.

Even then there were red flags: As far back as the 1970s, a landmark study by the California-based Rand Corp. had found that requiring people to pay more out of pocket caused them to cut back on medical care they needed as well as on unnecessary services.

Backers of the high-deductible strategy nevertheless argued that patients, given “skin in the game,” would become active consumers who would force drugmakers, hospitals and other medical providers to rein in prices.

“The thing that caught people’s imagination was this idea of unleashing American patients as consumers,” said Dr. Arnie Milstein, medical director of the California-based Pacific Business Group on Health, an organization of large companies, including Boeing, Safeway, Walmart and Wells Fargo.

Employers, desperate for a way to control healthcare spending, saw an opportunity to hold down costs.

Many of the first companies to offer high-deductible plans gave employees seed money for medical savings accounts, with the idea that the cash would help workers pay their deductibles. Within a few years, the George W. Bush administration — backed later by Congress — carved out tax benefits for the accounts.

As high-deductible plans caught fire, however, many employers saw they could save even more by not contributing to their employees’ accounts.

“The idea was hijacked,” said Tony Miller, a Minnesota healthcare entrepreneur who developed some of the first high-deductible plans for large employers like medical device giant Medtronic, but who has since grown disenchanted with how companies shifted costs onto patients.

The change left workers responsible for saving for healthcare on their own.

Yet government data show that most workers haven’t had extra money to set aside.

In 2016, the most recent year with available data, just half of single households and six in 10 multi-person households had even $2,000 in available savings — including cash, non-retirement stocks, mutual funds and other liquid assets — according to a KFF analysis of government data conducted for The Times.

“In the real world, average people are living paycheck to paycheck,” said Helen Darling, the former head of the National Business Group on Health, a leading employer organization focused on health benefits. “Unfortunately, that never got through to the policy debate.”

Moreover, the vision of legions of patients becoming engaged shoppers pushing down prices has turned out to be a mirage.

Only 17% of workers say they have attempted to shop around to find the best price for a medical service in the previous year, according to the Times-Kaiser poll.

And doctors, hospitals and clinics continue to make costs nearly impossible for patients to determine, according to consumer advocates, independent research and the Times/KFF survey. Two-thirds of surveyed workers said finding out the cost of a medical treatment or procedure was somewhat or very difficult.

Today, most Americans with a job-based health plan still give their insurance good marks. Two-thirds call their coverage excellent or good, according to the Times/KFF poll, which found that workers are primarily grateful to have any coverage.

But those with the highest deductibles are substantially less satisfied, with fewer than half giving their plans high marks.

Americans with chronic illnesses are more likely than healthy workers to say their insurance has gotten worse in recent years and less likely to feel the system works well for people like them, the poll found.

Across the board, large numbers of U.S. workers are looking for relief.

In a major reversal from 15 years ago, six in 10 Americans with job-based coverage now call affordability the most important feature of a health plan, outranking previous top concerns such as a broad choice of doctors and hospitals and a wide range of benefits.

“The whole situation drives me nuts,” said Bryan Shirley, a lawyer in Minnesota who said in the past he would question whether he needed to take his children to the doctor because he worried about paying the deductible. “It’s the worst feeling as a parent.”

Shirley, 46, said he put off medical attention for his sports injuries and at one point put thousands of dollars of medical bills on credit cards.

“I know we are better off than most,” he said. “But I feel like there must be a better way.”

He’s not alone.

A growing number of healthcare officials, and even some corporate leaders, say it’s time to reassess the cost-sharing revolution.

“I would love to see us reevaluate the whole purpose of co-pays and deductibles,” said McAneny, the American Medical Assn. president. “It makes no sense to put a barrier in front of care patients need to get.”

Even former Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt, a Republican who supported the move to higher deductibles as Health and Human Services secretary in the George W. Bush administration, acknowledged that adjustments may be needed, even if returning to the days of no-deductible coverage is not the solution.

“There needs to be a way to relieve the pressure,” Leavitt said. “Otherwise, people will feel like they have no insurance at all.”

More stories from Noam N. Levey »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.