Trying to shop for medical care? Lots of luck with that

WESTFIELD, Ind. — Rebecca Grimm tried to be a smart shopper when her second pregnancy ended in a miscarriage last year.

Grimm, who has a high-deductible health plan, first tried a $10 pill to clear the fetal tissue. When that didn’t work, she checked her insurance company website to compare the cost of a surgical procedure at several local medical centers.

All were around $900, she recalled. Grimm went to a center a few miles from her house. The procedure took 20 minutes.

The Grimms got a bill for $5,948.69.

“We thought something had to be wrong,” said Grimm, who is 29 and lives in a small house in the northern suburbs of Indianapolis. “Having a miscarriage was hard. Having to deal with medical bills for months afterwards was like salt in the wound.… It made no sense at all.”

High-deductible health plans, which are fast becoming the dominant form of coverage for U.S. workers, were supposed to empower patients. Backers said the plans would create engaged shoppers who would check prices and compare providers, forcing hospitals, doctors and drugmakers to control costs.

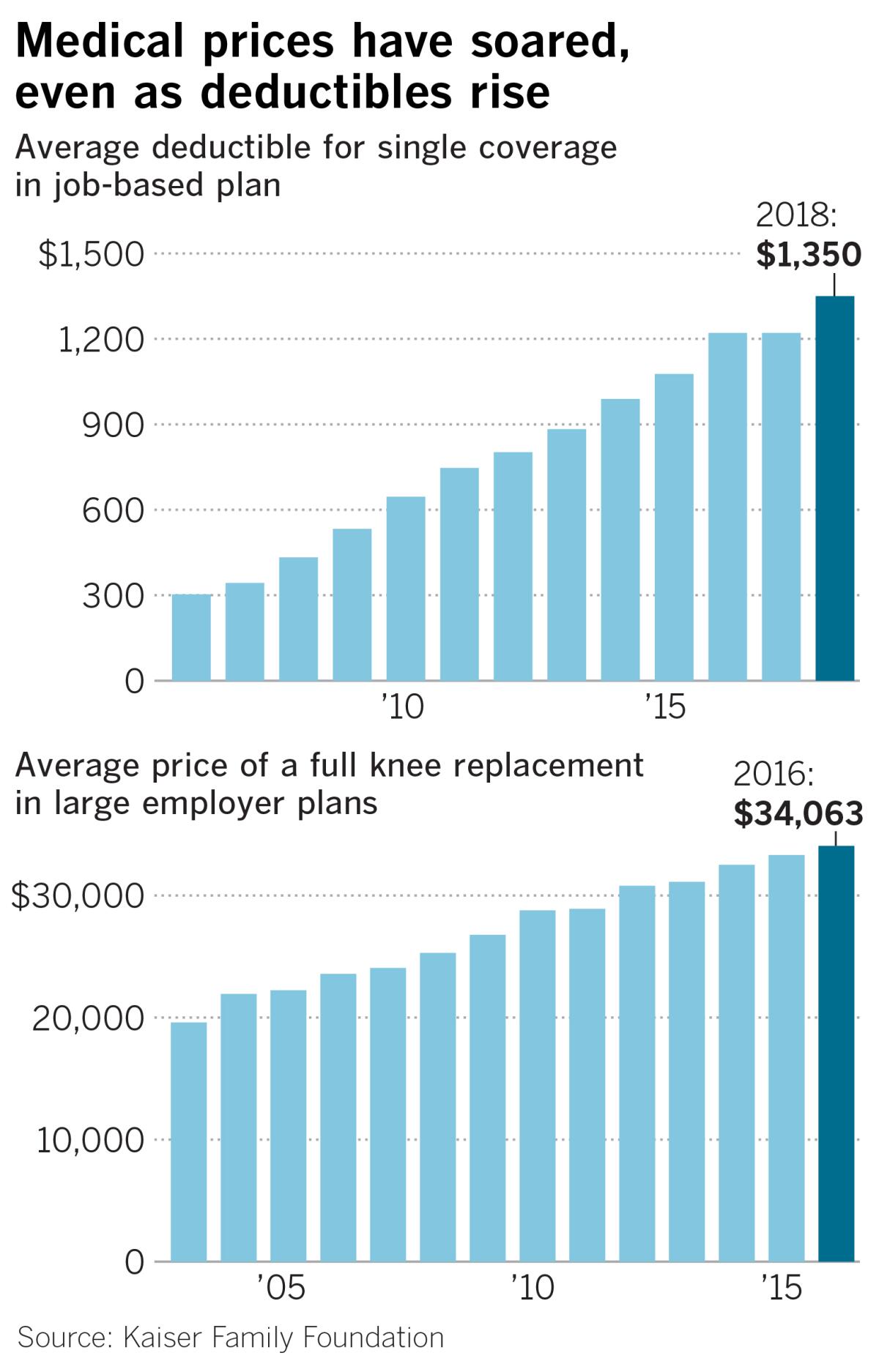

Deductibles have more than tripled over the last decade for people who get insurance through their jobs, but the promised consumer revolution never materialized. Instead, Americans have been left shopping in the dark and increasingly struggling with medical bills they can’t afford, a Times examination of job-based health insurance shows.

“This idea that we were going to give patients ‘skin in the game’ and a few shopping tools and this was going to address the broad problems in our healthcare system was poorly conceived,” said Lynn Quincy, former healthcare advocate at Consumer Reports now at Altarum, a nonprofit research and consulting firm.

“It’s clear now that the idea definitely hasn’t borne fruit,” Quincy continued. “It hasn’t made people feel more confident seeking care. It hasn’t led to better value. And it’s had terrible consequences on patients’ ability to afford care.”

With healthcare costs topping the list of Americans’ anxieties, the Times undertook a comprehensive examination of the nation’s affordability crisis and the toll it’s taking on working Americans and their families.

Although Americans are willing to seek out lower-priced generic medications, few are comfortable shopping for medical care, studies and surveys show. Patients like Grimm who do try are often frustrated by incomplete or inaccurate information from insurers, hospitals and other medical providers.

Just 1 in 6 covered workers even tried to shop for the best price for a medical service in the previous year, according to a nationwide poll conducted for this project by The Times and the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. Two-thirds of workers with job-based coverage said finding the cost of a medical treatment or procedure was somewhat or very difficult.

Meantime, prices for medical care and prescription drugs haven’t moderated, as advocates of high-deductible insurance predicted. Instead, they have soared.

The average price of a knee replacement, for example, shot up nearly 80% between 2003 and 2017, increasing at more than double the rate of overall inflation, a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of commercial insurance data found.

These price hikes are crushing insured Americans: 1 in 6 workers with job-based benefits in the Times/Kaiser Family Foundation poll reported that they had to make a “difficult sacrifice” in the past year to pay for healthcare, such as cutting back on food and other essentials.

“We overestimated the ability of consumers to be good stewards of their healthcare dollars in a system that is very unfriendly to consumers, and underestimated the support they would need from us,” said Dr. Marcus Thygeson, a former Blue Shield of California executive who worked on early efforts to develop so-called consumer-directed health plans.

Early champions of high-deductible health insurance — including benefit consultants, conservative health-policy advocates and Republican politicians such as former House Speaker Newt Gingrich — promised something very different when they sold employers on shifting more costs onto workers in the early 2000s.

“When consumers apply pressure on an industry, whether it’s retailing or banking, cars or computers, it invariably produces a surge of innovation that increases productivity, reduces prices, improves quality and expands choices,” Harvard Business School professor Regina Herzlinger wrote in an influential 2002 essay. Herzlinger became a leading proponent of having patients put more “skin in the game.”

By some measures, healthcare markets appeared ripe for an intervention.

Then and now, prices for the same medical service can vary dramatically from one hospital or doctor’s office to another.

In Philadelphia, for example, the price of a colonoscopy ranges from less than $1,000 at some hospitals to nearly $4,000 at the most expensive, researchers at the Health Care Pricing Project found by analyzing commercial health insurance data from around the country.

Similarly, the lowest-priced hospitals in Houston billed as little as $15,000 for a knee replacement, while the costliest charged more than $35,000.

That kind of price variation — which has little relationship to quality, according to a growing number of studies — spawned online tools that were supposed to help patients find the most economical place to get care.

“There was this notion that if people could figure out where to buy the cheapest Kleenex, they could pick doctors and hospitals, too,” said Dr. Arnie Milstein, medical director of the California-based Pacific Business Group on Health, an organization of large companies including Boeing, Safeway, Walmart and Wells Fargo.

Finding medical care is more complex than choosing facial tissue, however. And few workers ended up using these tools.

In one study of nearly 150,000 people covered by two large national employers, only about one in 10 who could shop for price information did, even if they had a high-deductible plan. And use of the tool was not associated with lower healthcare spending.

In the Times/Kaiser Family Foundation survey, only about a quarter of workers with job-based coverage reported using an online cost tool.

Americans show little inclination to find the best deal even for a basic medical service like an MRI scan, which can be as much as five times more expensive in one facility than in another, another recent study found.

Researchers analyzing commercial insurance data from tens of millions of Americans reported only 14% of patients went to the lowest-cost MRI within a 30-minute drive of their house. Patients on average passed six lower-priced MRI facilities on their way from home to the place where they had the imaging, the study found.

Many Americans don’t want to have to shop for healthcare, preferring to let their physicians guide their care.

“We pretty much go where we’re comfortable. We’re not looking for the cheapest doctor,” said Jim Morrissey, 39, a food service manager who lives near Harrisburg, Pa. “I’m loyal to the doctors I trust.”

Americans’ lack of enthusiasm for medical shopping also reflects how little information is available about prices.

The wildly inaccurate estimate that Grimm got for her procedure in Indiana is hardly unique.

When researchers in 2011 and 2012 called a sample of 122 hospitals across the country to get a price for a hip replacement, a common and usually straightforward elective surgery, only 19 were able to provide a complete estimate, including the hospital and physician costs.

Even when the researchers called a physician’s office separately to get doctors’ fees, they could get a full estimate less than half the time.

Four years later, when a second group of researchers repeated the exercise with the same hospitals, the results were worse: Only eight gave a complete estimate.

Information on the quality of medical services, which patients would need to be informed shoppers, is even harder to come by.

Hospitals that can provide a single price for something like a hip replacement typically “bundle” all the services required for the procedure, including the surgeons’ fees, the anesthesia, the use of any medications and the cost of using hospital facilities such as the operating and recovery rooms.

But that’s not the way most medical care in the U.S. is billed. Rather than a single price, hospitals, doctors and other medical providers rely on approximately 10,000 individual billing codes to charge for services. A consumer who wanted to shop would have to price each service separately.

When Grimm finally succeeded in getting an itemized bill from the surgical center, she and her husband were floored by the 23 individual charges, including: $65.23 for Lidocaine, an anesthetic; $133.28 for two injections of Ondansetron, a drug to prevent nausea and vomiting; $413 for oxygen; $132.80 for a liter of sterile water.

There were two charges for the surgery itself of $2,380 and $9,782. Grimm’s brief stay in the recovery room cost $720.

“How in the world were we supposed to know how to shop for all that?” she said.

Herzlinger, the Harvard Business School professor, said in a recent interview that the consumer revolution she envisioned didn’t occur because hospitals and doctors resisted efforts to make healthcare pricing more transparent.

“There are a lot of people who don’t want this information revealed,” she said, adding she never believed consumer-directed healthcare required high deductibles. “I personally think deductibles are too high,” she said.

Shopping becomes even more unrealistic for a person with an emergency — chest pain, for example, or an automobile accident.

Nor would a patient have either the ability or much incentive to compare costs for a complex disease like cancer that may require months of chemotherapy, radiation and other expensive and often-unpredictable medical services, the price of which would likely exceed even the highest deductibles.

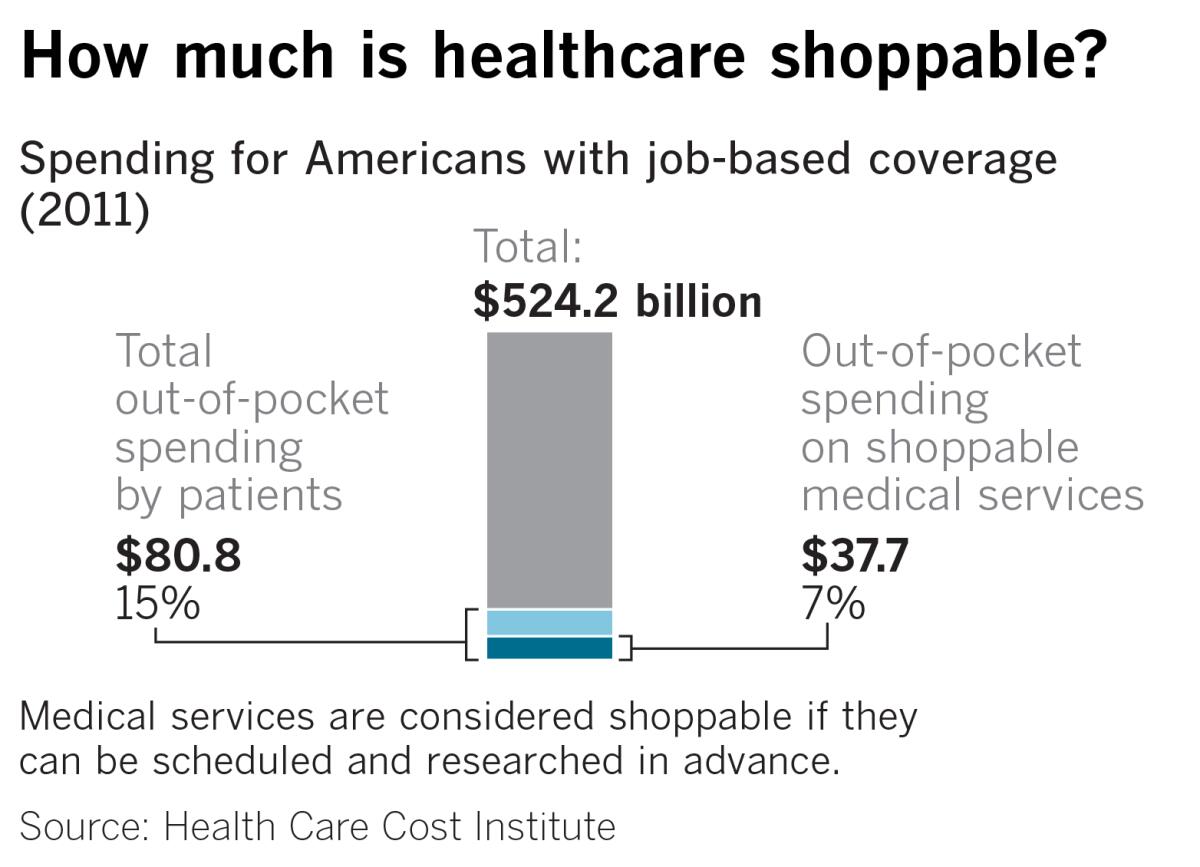

By one estimate by the Health Care Cost Institute, just 7% of total healthcare spending for Americans with job-based coverage was on medical services that could be considered “shoppable” because the service required an out-of-pocket payment and the procedure could be researched in advance.

“The fact is very little medical care is shoppable,” said David Newman, the institute’s former director, noting that medical care is not like other services that Americans typically buy.

“We become good shoppers when we are repeat shoppers,” he said. “If you buy a new car every three years, you can become an informed shopper. There is no way to become an informed shopper for your appendix. You only get your appendix out once.”

Julie Hernandez, a 61-year-old graphic designer in Oregon, discovered the limits of medical shopping the hard way when she went to a dermatologist earlier this year to get a small cancerous growth removed from her nose.

Sensitive to costs, in part because she had a high-deductible plan, Hernandez tried to get estimates from several medical offices in her area around Medford. She selected what seemed to be the lowest-cost option, even though she was told the procedure might cost $3,000 to $8,000.

Midway through the surgery, after the doctor had removed several layers of skin from Hernandez’s nostril to take off the cancerous tissue, the doctor asked Hernandez as she lay on the operating table whether she wanted to have the wound closed with skin from her cheek or from another part of her nose.

“I had a gaping hole the size of a dime in my nose,” she said. “At that point, money didn’t come into play. I went with the option the doctor said was best.”

Hernandez later got a bill for $5,568.

As for the Grimms, they ultimately got a discount for Rebecca’s procedure after she spent months filling out forms and negotiating with the surgery center. They ended up paying $2,300.

But as she prepared to have a second baby this summer, the couple didn’t even try to shop for the best price, though they knew they’d have to pay thousands of dollars for the delivery.

“It’s basically impossible to do,” Grimm concluded.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.