Bread for the poor, SALT for the rich: Why some affluent Californians would get a big break from Democrats

WASHINGTON — One of President Biden‘s proudest boasts is that his legislative package reflects a “blue-collar blueprint” for prosperity.

The $1.2-trillion infrastructure bill he signed into law on Monday aims to produce a lot of jobs over the next 10 years for plumbers, pipe fitters and construction crews — work that doesn’t require a college degree.

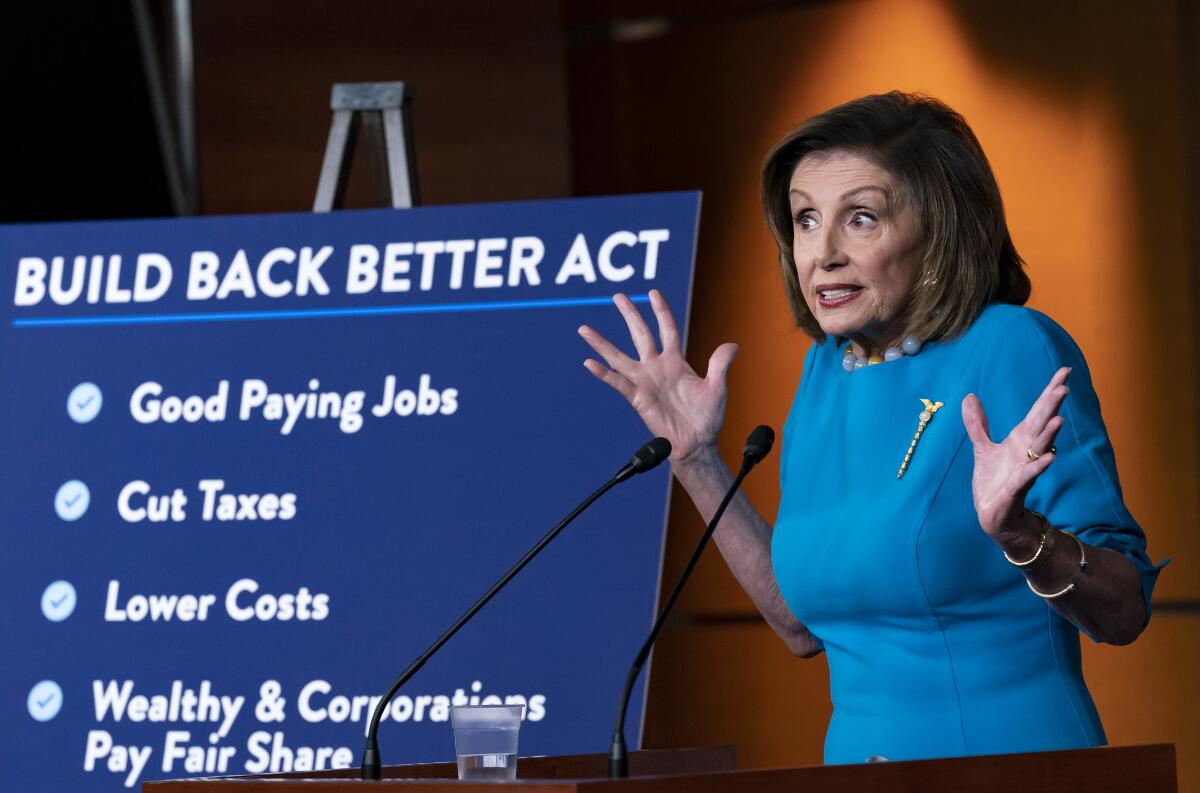

The even larger Build Back Better legislation, on which Democrats hope to complete work before Christmas, will also produce a lot of jobs for Americans who didn’t go to college. Its benefits would go especially to fields such as childcare, which, unlike construction, has a mostly female workforce.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Both bills reflect a core Democratic belief in actively using government to improve the lives of less-affluent Americans. They also reflect Biden’s conviction that Democrats need to do more for blue-collar Americans after years of stressing the benefits of getting more Americans to go to college.

There’s another part of the picture, however, which says something else important about the Democrats: One of the biggest parts of the Build Back Better bill delivers the lion’s share of its benefits to the affluent.

SALT rollback irks progressives

The Build Back Better law aims to accomplish a lot — so much so that its scope has become one of the administration’s biggest communications problems. Officials have had trouble coming up with a way to summarize the bill beyond its price tag, about $2 trillion over 10 years in the version that the House passed Friday, with all but one Democrat voting in favor.

The bill would help seniors by cutting the cost of some prescription drugs and expanding Medicare to cover hearing aids; it would help young children and their parents by expanding subsidies for childcare and creating widely available pre-kindergarten programs for 3- and 4-year olds; it would extend the universal child tax credit for another year and make it permanently refundable, a move that scholars believe would cut the child poverty rate nearly in half; and it would devote some $555 billion to expanding clean energy and combating climate change.

It would also greatly increase the tax deduction that families can take to offset state and local taxes, known in legislative jargon as SALT. In the House-passed bill, 94% of that benefit would go to families in the top fifth of American incomes, with almost three-quarters flowing to those in the top 6%, according to the Washington-based Tax Policy Center.

The SALT deduction was limited to $10,000 a year in the Republican tax bill in 2017. The House bill would raise that limit to $80,000, which would reduce federal revenue by about $300 billion over the next five years.

The price tag makes SALT one of the biggest single elements of the package, a fact that has galled some progressive lawmakers. In the zero-sum game of legislative trading, covering the cost has meant leaving out money for other social programs that benefit low- and middle-income households.

Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.), who has seen his proposals to permanently extend the child tax credit whittled back, denounced the House plan Thursday as “preposterous.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont issued a statement earlier this month in which he blasted the then-current version of the increased SALT deduction.

“At a time of massive income and wealth inequality, the last thing we should be doing is giving more tax breaks to the very rich,” he said.

“I am open to a compromise approach which protects the middle class in high-tax states,” Sanders added. “I will not support more tax breaks for billionaires.”

How much of the benefit from raising the SALT limit will go to top earners has roiled Democrats for weeks. A heavy skew to upper-income taxpayers is inevitable with any SALT expansion since only about 10% of American taxpayers still itemize their deductions, mostly those with incomes well above average. But progressives have pushed to phase out the benefit for people at the top of the ladder.

Sanders’ call for a compromise was the key part of his statement. A savvy legislator, he knows that restoring some form of the SALT deduction is a political necessity for many of his Democratic colleagues. And he can be pretty sure the Senate will pare back what the House passed.

Democrats of all factions also know that the relatively well-off suburban and urban voters who benefit most from the SALT deduction have become a key part of the Democratic voting base.

Over the last generation, as Republicans have made more and more gains among blue-collar, white voters, Democrats have gained among the college-educated. As a result, Democratic electoral successes rest on two pillars that aren’t always aligned — college-educated liberals, mostly white and often relatively affluent, and voters of color, many of whom have much lower incomes.

The two join in the belief that government should do more to solve problems. The Pew Research Center’s recent political typology study found that belief to be one of the core views that unites all Democratic factions and clearly separates them from Republicans.

But while they share an ideology, the economic interests of the Democrats’ affluent and working-class constituencies sometimes diverge. And while Americans of all stripes often vote in ways that conflict with their pure economic interests, there are limits.

The SALT deduction appears to be one of those. As a result, it highlights one of the tensions in the Democratic coalition.

Republicans have exploited that tension, pummeling Democrats for their “tax cut for the rich.”

Democratic leaders have tried to rebut that by arguing that the SALT deduction protects public services.

“It’s not about tax cuts for wealthy people. It’s about services for the American people,” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) said Thursday.

“This isn’t about who gets a tax cut. It’s about which states get the revenue that they need in order to meet the needs of the people,” she said.

Democrats also note that while the affluent would be winners from restoring the SALT deduction, their legislation in total would still sharply raise taxes at the very top. The House-passed bill would increase taxes by an average of $55,000 for those in the top 1%, who make about $885,000 or more, the Tax Policy Center estimates. Those in the top 0.1%, who make about $4 million or more, would be hit with an additional $585,000 on average.

The SALT deduction has long roots — stretching back to the earliest days of the federal income tax. In recent years, it became the center of political battle.

The GOP’s campaign against it features the mirror image of Pelosi’s argument: Allowing Americans to deduct state and local tax payments makes it too easy for liberal state governments to raise taxes, Republicans say.

In 2017, Republicans finally had the votes to put their campaign argument into law. The $10,000 limit they enacted was high enough to ensure a full deduction for the vast majority of taxpayers in red states while slapping a big tax increase on many Americans in high-cost blue states like California, New York and New Jersey.

Of course, while income distribution tables show that the vast majority of the taxpayers affected by the limit enjoy incomes in the top 10%, those hefty earnings don’t necessarily make people in high-cost areas feel rich — or even extremely affluent. The tax increase generated a sharp backlash that probably played some role in big Republican losses in 2018 in places like Orange County and similar high-cost suburbs in the New York and Philadelphia regions.

Republicans from those areas, like Orange County Rep. Michelle Steel, made restoring the SALT deduction a top priority. But because expanding the deduction forms part of the overall Biden spending bill, they’re against it.

California’s state Finance Department estimates that about 2.3 million taxpayers in the state could benefit from raising the cap to $80,000. That’s a lot of voters.

And that provides the final twist in the SALT saga: Republicans nationally can enjoy taking shots at Democrats for restoring the deduction, but for their colleagues in hotly contested suburban districts, no SALT could prove, well, unappetizing.

Biden hits the road

Having signed the infrastructure bill into law, Biden has hit the road to sell Americans on its benefits. Wednesday brought him to Detroit, where he took an electric SUV for a test drive and said, “We’re going to make sure that the jobs of the future end up here in Michigan, not halfway around the world,” Arit John and Erin Logan reported.

On Thursday, Biden held his first in-person meeting as president with his Mexican counterpart, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. One big issue for the two countries is climate change — Washington would like Mexico to begin moving away from fossil fuels. But Biden may not be in a position to press that case because he desperately needs López Obrador’s cooperation in reducing migration across the border, Kate Linthicum and Chris Megerian wrote.

Our daily news podcast

If you’re a fan of this newsletter, you’ll love our daily podcast “The Times,” hosted every weekday by columnist Gustavo Arellano, along with reporters from across our newsroom. Go beyond the headlines. Download and listen on our App, subscribe on Apple Podcasts and follow on Spotify.

United States of California

When the San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District ignored community members and activists and voted to exempt four refineries from new rules requiring high-tech air monitoring equipment, California’s attorney general weighed in on the side of the residents, joining environmental groups to sue the air regulators.

The tough legal stand showcases California’s model for protecting communities that have borne more than their share of environmental hazards.

That’s a model that other states and the Biden administration are working to replicate, Evan Halper and Anna Phillips wrote. The piece is the latest in The Times’ series exploring California’s impact on national policy.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest from Washington

Last year, when Biden chose Kamala Harris as his running mate, many Democrats saw her as an eventual successor — perhaps as soon as 2024. Now, as Noah Bierman and Melanie Mason report, the idea of Harris replacing Biden is giving a lot of Democrats anxiety. Growing worries over Harris’ political stature are colliding with concerns that any move to sideline her would alienate voters the party needs.

The House voted 223-207 to censure Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.) and strip him of his committee assignments as punishment for a social media posting of a violent animated video showing himself killing a Democratic colleague. Two Republicans joined the Democrats in censuring Gosar.

The vote further worsened the tense relationship between Pelosi and Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield), Nolan McCaskill wrote. Pelosi questioned McCarthy’s leadership, while McCarthy threatened that House Republicans would retaliate if they regain control of the chamber after next year’s elections.

The Supreme Court on Dec. 1 is scheduled to take up a high-profile abortion case from Mississippi, testing whether a state can ban most abortions after 15 weeks — something not permitted since the high court’s 1973 Roe vs. Wade decision, which legalized abortion up through the second trimester. As David Savage reported, a new nationwide poll finds that by a 2-1 ratio, Americans said Roe vs. Wade should not be overturned, but when asked about a 15-week limit, the public was closely divided, with 37% saying they favored it and 32% opposed.

Progressive Democrats aggressively used their clout in battles over the past couple of months on the Build Back Better bill. But, McCaskill reported, many within their ranks are uncertain about which other legislative battles they should engage in.

The latest from California

The state’s legislative analyst projects a huge budget surplus — some $31 billion. As John Myers reported, that good news brings a bunch of headaches for state lawmakers, in part because of the state’s extremely complex spending rules.

Kevin Faulconer, the former San Diego mayor, flopped as a candidate for California governor, winning just 8% in the recall election. But he’s gearing up to try again, Mark Barabak wrote. The recall campaign became all spectacle and no substance, he says. In a substantive debate, he thinks his brand of relatively moderate Republican policies might stand a chance against Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Mayor Eric Garcetti is still awaiting a hearing in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on his nomination to be ambassador to India. As Dakota Smith reported, Garcetti’s been on hold for four months, with no immediate signs of a reprieve. In part that’s because Democratic leaders have made other nominations a priority, including former Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel‘s bid to be ambassador to Japan. But the Senate panel’s staff is also continuing to look into whether Garcetti knew about alleged sexual harassment by a former top advisor.

California expects to receive a lot from the infrastructure bill, Logan reported, with a rundown of major provisions.

Sign up for our California Politics newsletter to get the best of The Times’ state politics reporting.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.