Democrats’ bill plans the biggest expansion of public education in a century

Democrats are seeking to provide universal preschool and subsidized child care in one of the largest pieces of the Build Back Better social spending bill.

WASHINGTON — Largely overlooked amid the fights on Capitol Hill over immigration, drug pricing and paid family leave, Democrats’ plan to transform how the nation provides early child care stands out as one of the most expensive and sweeping provisions of their $1.85-trillion social safety net bill.

Costing $390 billion, the proposal would provide universal preschool access for 3- and 4-year-old children — the largest expansion of free education since public high school was added about 100 years ago. It would also subsidize the cost of child care for the vast majority of parents with a child under 6.

Together, the provisions would convert early childhood education and child care in the U.S. from a private, disparate network that favors the wealthy into a taxpayer-funded system that could ease the burden for millions of working parents and low-income families. Democrats are beginning to focus on the child-care provisions as a generational change that will resonate with voters.

“This is the stuff of legacy,” said Melissa Boteach, a vice president at the National Women’s Law Center. “When you reconceive of child care as a public good, which this bill does, you understand that it’s unaffordable for parents. And providers are already earning poverty wages. The way you crack that nut is by large-scale public investment.”

Democrats argue that parents — typically mothers — cannot be full participants in the workforce if their children are not in affordable, high-quality care programs.

They also point to a significant disparity between the U.S. and other developed Western countries that provide preschool. As of 2019, only about half of American 3- and 4-year-olds were enrolled in preschool, according to federal statistics.

“I have had kindergarten teachers tell me that, on the first day of school, they have kids who do not know how to turn a page in a book or pick up a pencil. They automatically start way behind,” said Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), a former preschool teacher who has been advocating for the policy for decades. She introduced the legislation alongside Rep. Robert C. Scott (D-Va.).

Republicans counter that the proposal allows the government to take control of decisions better left to parents. With next year’s midterm election in mind, they say it fits into a broader narrative of Democrats interfering in education, such as pandemic closures and school mask mandates.

“The Biden administration wants to insert itself into the most intimate family decisions and tell parents how to care for their toddlers,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). “Democrats want to sweep the first five years of children’s lives into a new set of top-down, one-size-fits-all, Washington-knows-best regulations.”

Several Republicans have complained the policy would exclude faith-based preschool or day-care programs.

But under the plan, any program would be able to participate as long as it meets state and federal requirements, and child-care centers and parents could choose not to participate.

Republicans say those federal parameters would still leave out some people, such as child-care centers that don’t want to comply with the new rules or families in which grandparents provide child care or one parent chooses to not work outside the home.

Murray said the change is long overdue and is particularly needed during the pandemic.

“We have a country where women can’t be at work. We have employers who are looking for qualified workers,” she said. “The way we support families, the way we value families, and the way that we make sure that families are secure in this country is by eliminating barriers that keep [women] from being able to do what they need to care for their families.”

The child-care and preschool policies will take time to fully implement and would be in place only through 2027 — a constraint that will make successful and early implementation politically important to Democrats, who will want to ensure a future Congress will feel political pressure to renew it.

“You’re not going to be able to take your kid to pre-K next week or next year even,” said Rep. Jackie Speier (D-Hillsborough). “It’s the nature of doing something that is that transformative. We’re going to have to prepare everyone, but it’s so far past time for us to do these things.”

In a bill that has been substantially cut from what Democrats had originally hoped to enact, the child-care policies have been relatively well protected and noncontroversial among Democrats.

Under the proposed policy, all 3- and 4-year-old children, including those without legal status, would be guaranteed access to preschool regardless of their parents’ income, the largest expansion of universal and free education since localities established public high school a century ago, according to the National Women’s Law Center. However, attendance at preschool would be voluntary.

In addition, parents of a child under 6 who make up to 2.5 times the state median income — or about $233,760 for a family of four in California this year — would be provided assistance on a sliding scale to help cover the cost of child care, capped at 7% of their income.

The result would be lower child-care costs for more than 90% of families with young children, according to a group of child advocacy organizations that support the bill.

States would decide whether to participate in the program. A state or region that accepts would shape the policy within federal parameters.

In general, policy experts expect states would set up systems in which parents could choose from a list of participating child-care centers. Subsidies would go directly from the federal government to the child-care center on behalf of the eligible parent. Alternatively, parents could get a voucher to pay their child-care provider directly.

A spokesperson for Gov. Gavin Newsom said he “looks forward to utilizing federal dollars to build on California’s child-care program.”

Earlier this year, California approved a universal program for 4-year-oldsthat relies predominantly on public schools, as opposed to the federal plan, which would rely on a mixed-delivery system of various kinds of schools.

The combination of the state and federal programs could provide Californians with access to many different pre-K venues, according to Linda Asato, executive director of the California Child Care Resource & Referral Network, an educational policy organization.

“It helps California expand its vision of preschool to include more community-based organizations,” Asato said. It would allow the state to expand preschool in a way it isn’t able to now, she said.

Mindful that many Republican-led states opted against participating in Obamacare’s expansion of Medicaid, Democrats said that if a state refuses to use the program, a locality could still do so.

Child-care centers that participate — whether they are day-care centers, public schools, faith-based institutions or Head Start programs — would have to operate within federal parameters, which would be spelled out more explicitly by the Biden administration.

Federal and state regulations would determine details such as the length of a preschool day and year, and academic requirements for certain teachers.

In an attempt to address the severe shortage of workers, employers would also have to provide living wages comparable to those of elementary school workers with similar credentials.

Due to the worker shortage, full implementation would take time, and parents’ child-care costs could increase before the subsidies are in full effect as providers hire more staff and meet new educational requirements.

If the program is launched next year as planned, only families making under the state median income — $93,504 for a family of four in California this year — would be eligible for subsidies. The plan’s supporters expect that additional costs for parents would be made up for when subsidies are rolled out to all income levels.

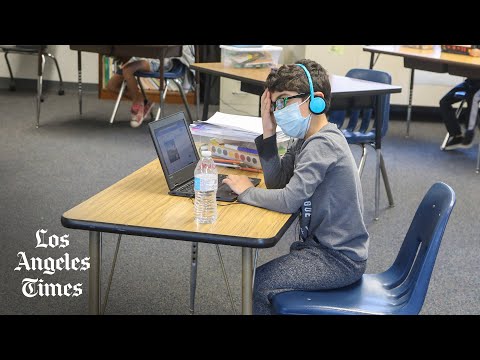

The pandemic’s closure of schools and day-care centers brought the child-care industry’s problems into sharper focus, particularly low wages that have driven people from the profession.

The national median wage for an early childhood worker was between $11.65 and $14.67 per hour before the pandemic, according to the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at UC Berkeley. The industry still has not recovered.

Child-care centers haven’t increased wages because doing so could raise prices out of reach of many parents.

“What this bill does is solve this market failure,” said Julie Kashen, a director and senior fellow at the Century Foundation. “The government is coming in and saying we are going to solve this problem by putting the money in to raise wages for the early educators and lower costs for parents.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.