New look at political groups explains rancor between Democrats and Republicans — and within parties

WASHINGTON — The widening and increasingly bitter divide between Republicans and Democrats defines American politics, but in recent weeks, it’s the divisions inside each of the two parties that have dominated headlines.

Democratic progressives have fumed at moderate lawmakers who have insisted on cutting the size of President Biden’s social spending plans.

Republicans have denounced 13 of their House colleagues who sided with Democrats earlier this month to pass Biden’s $1.2-trillion infrastructure bill. After conservative Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.) posted their phone numbers on social media, some of the 13 reported getting death threats.

What issues create the deep fissures within the two parties, and which Americans make up the conflicting factions?

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

For some 30 years, many of the best answers to those questions have come from a project of the nonpartisan Pew Research Center — a long-running effort to analyze the political groupings into which Americans cluster, which Pew refers to as a political typology.

Pew released its latest typology on Tuesday, the eighth in the series. The results are key to understanding why American politics works the way it does.

Parties driven by their extremes

For this latest effort, Pew surveyed 10,221 American adults, asking each of them a series of questions about their political attitudes, values and views of American society. Researchers took the results and put them through what’s called a cluster analysis to define groups that make up U.S. society.

The new typology divides Americans into nine such groups — four on the left, which make up the Democratic coalition, four on the right, making up the Republican coalition, and one in between whose members are largely defined by a lack of interest in politics and public affairs.

Nearly all the Democrats agree on wanting a larger government that provides more services; nearly all the Republicans want the opposite.

And nearly all Democrats believe that race and gender discrimination remain serious problems in American society that require further efforts to resolve. On the Republican side, the belief that little — if anything — remains to be done to achieve equality has become a defining principle.

On other issues, however, the parties have deep internal splits. In each, the most energized group — the people who most regularly turn out to vote, post on social media and contribute to campaigns — stands at the edges.

On the right, that would be an extremely conservative, religiously oriented, nationalistic group which Pew calls the Faith and Flag conservatives. At the other end of the scale stands a socialist-friendly, largely secular group it calls the Progressive Left.

On several major issues, those two groups have views that are “far from the rest of their coalitions,” yet they’re “the most politically engaged groups, and they’re driving the conversation,” said Carroll Doherty, Pew’s director of political research.

The Faith and Flag conservatives, who make up about 10% of American adults and almost 25% of Republicans, have shaped the party’s policies on some social issues such as abortion, but have even more strongly affected its overall approach to politics. A majority (53%) of the group, for example, says that “compromise in politics is really just selling out.”

That has strongly shaped the GOP’s approach to legislation and helps explain the bitter, angry response to the Republicans who voted for Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure compromise.

The group is overwhelmingly white (85%), relatively old (two-thirds are 50 or older) mostly Christian (4 in 10 are white, evangelical Protestants) and heavily rural.

Their mirror image, the Progressive Left, is a significantly smaller group, only about 6% of Americans and 12% of Democrats. Despite their smaller size, however, they have had a strong impact, moving their party to the left, especially on expanding government and combating climate change.

That group is in several ways the opposite of the Faith and Flag conservatives: urban, secular and significantly more college-educated than the rest of the country.

Like the Faith and Flag group, however, the Progressives are mostly white (68%) — the only Democratic faction with a white majority.

The groups have one other trait in common — each has a deep, visceral dislike of the other party.

While those two set the parameters of a lot of American political debate, it’s the other groups in each party’s coalition that explain why the Democratic and Republican approaches to government have diverged so widely.

On the Democratic side, the two biggest blocs, which make up just over half of Democratic voters, fit comfortably into the party establishment.

The Establishment Liberals (think Vice President Kamala Harris or Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg) are a racially diverse, highly educated (one-quarter have post-graduate degrees), fairly affluent group that is optimistic in its outlook, liberal in its politics and strong believers that “compromise is how things get done” in politics.

The Democratic Mainstays (think House Democratic Whip James E. Clyburn of South Carolina or President Biden) are more likely to define themselves as political moderates and are significantly more likely than other Democrats to say that religion plays a major role in their lives. Roughly 40% of Black Democrats fit into this group.

The Mainstays are more likely than other Democrats to favor increasing funds for police in their neighborhoods and somewhat less likely to favor increased immigration, but are extremely loyal to the Democratic Party.

Together, those two groups give Democrats a strong orientation toward cutting deals, making incremental progress and getting the work of government done.

Virtually the opposite is true of Republicans, whose two largest groups, the Faith and Flag conservatives and what Pew calls the Populist Right, dislike compromise and harbor deep suspicions of American institutions. Together, those groups, which make up nearly half the GOP’s voters, have produced a party that revels in opposition but has often found itself stymied when trying to govern.

The Populists group, the one most closely identified with former President Trump‘s style of politics, has a negative view of huge swaths of American society — big corporations, but also the entertainment industry, tech companies, labor unions, colleges and universities, and K-12 schools.

Nearly 9 in 10 of them believe the U.S. economic system unfairly favors the powerful, and a majority support raising taxes on big companies and the wealthy. Both of those views put them at odds with the rest of the GOP, helping explain why the party struggles to come up with economic proposals beyond opposition to Democratic plans.

The Populist Right also overwhelmingly says that immigrants coming to the U.S. make the country worse off. That puts them in conflict with the party’s smaller but still influential business-oriented establishment.

About half the Populist group say that white people declining as a share of the U.S. population is a bad thing, more than in any other group.

The Republican establishment faction (think Majority Leader Sen. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky or Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah) is what Pew calls the Committed Conservatives, pro-business, generally favorable to immigration and more moderate on racial issues.

A lot of Republican elected officials fall into that group, but unlike the very large establishment blocs on the Democratic side, relatively fewer voters do — 7% of Americans and 15% of the GOP. That creates a pervasive tension between GOP elected officials and many of their constituents.

Unlike the two larger conservative blocs, in which majorities want to see Trump run again, most Republicans in this group would prefer him to take a back seat.

Each of the coalitions also has a group that is alienated from its party.

A significant number in the Ambivalent Right, a younger, socially liberal, largely anti-Trump group within the GOP, voted for Biden in 2020.

On the Democratic side, the mostly young people in the Outsider Left are very liberal, but frustrated with the Democrats and not always motivated to vote. When Democratic political figures talk about the need to boost voter turnout, those are the potential voters many of them picture.

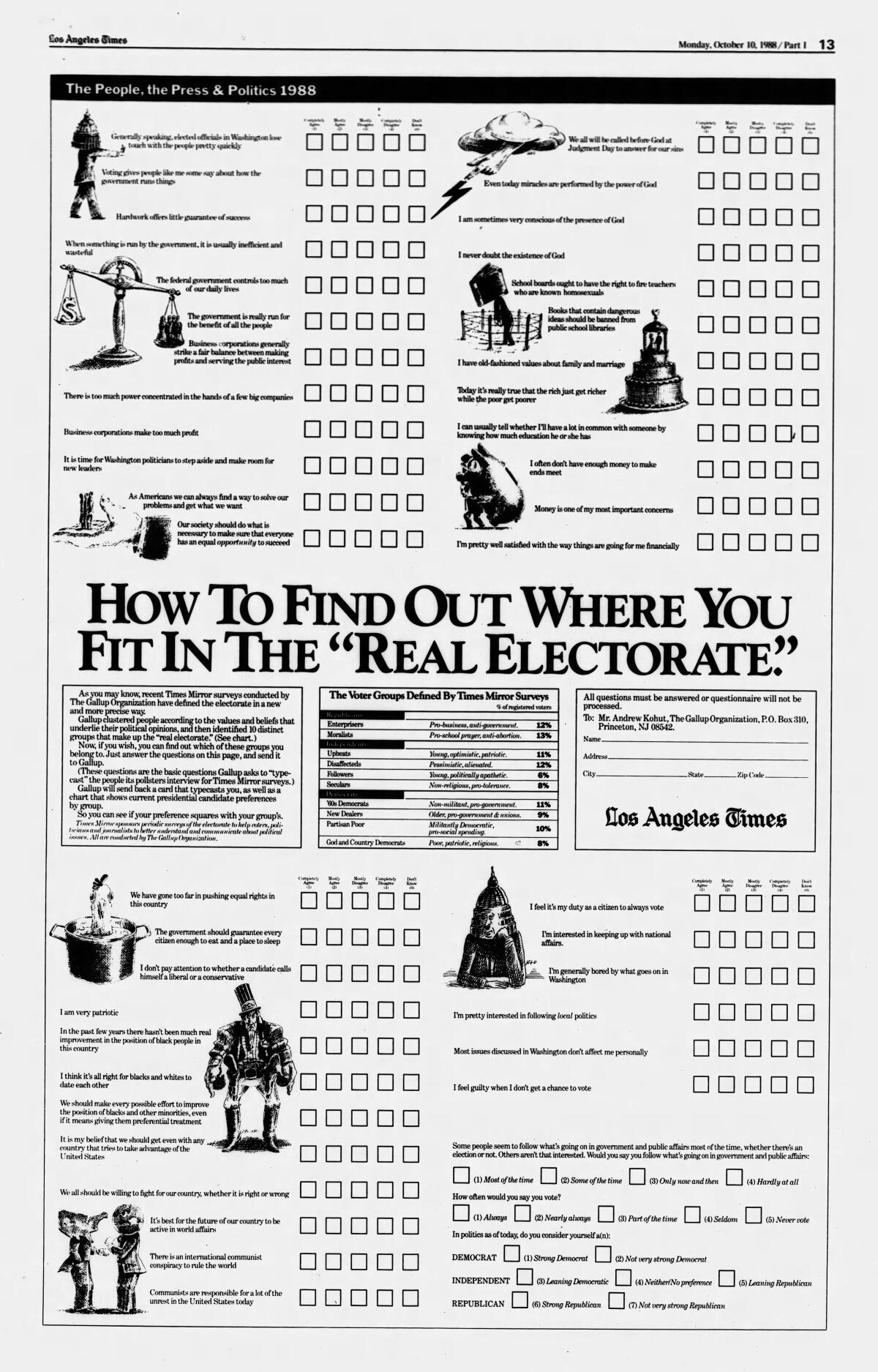

By the way, there’s a long connection between the Los Angeles Times and the political typology project. The first version of the political typology dates back to 1987 and was developed by the long-ago Times Mirror Center for the People and the Press, a research organization founded by the company that owned The Times.

To allow readers to see how they compared to the political types in that era, The Times published the typology quiz as a full-page in print, inviting people to fill it out, mail it in and get a letter back telling them what group they belonged to. Today, you can do it all online.

Where do you fit?

From the hard-right Faith and Flag Conservatives to the socialist-friendly Progressive Left, with seven stops in between, Pew’s political typology describes nine groups into which Americans can be divided. The typology comes along with a quiz that allows you to see which group most closely matches your views on major issues.

The vice president abroad

On a trip this week to France, Harris is introducing herself to the world in personal terms, Noah Bierman wrote. The trip, he said, has given Harris a chance “to reveal herself on the world stage — highlighting her status as the first woman and the first woman of color to serve in such high office — after 10 months of focusing on responding to the COVD-19 pandemic and other crises,” which have taken a political toll.

Part of Harris’ goal in the trip is to further mend relations with France, which were strained when the administration struck a deal with Australia to help build nuclear submarines, which wiped out a major French contract to build boats for the Australian navy. In her speeches, however, Harris has also tried to make the case that the U.S. has moved past the Trump era and once again can be relied upon as an ally, Bierman wrote. That’s met with some skepticism from Europeans, who wonder what will happen in the next election.

Meantime, Mark Barabak looked at how Harris has adopted a much lower public profile of late. As past occupants of the office, including George H.W. Bush and Al Gore have found, the number-two job is an “inherently diminishing one,” he wrote.

Our daily news podcast

If you’re a fan of this newsletter, you’ll love our daily podcast “The Times,” hosted every weekday by columnist Gustavo Arellano, along with reporters from across our newsroom. Go beyond the headlines. Download and listen on our App, subscribe on Apple Podcasts and follow on Spotify.

The continued racial impact of freeway projects

The U.S. has largely stopped building new freeways, but projects to widen or extend existing roads continue to displace thousands of Americans, with a particularly harsh impact on communities of color, Liam Dillon and Ben Poston reported.

Their investigation, based on thousands of documents and Transportation Department data, shows that more than 200,000 people have lost their homes nationwide to federal road projects over the last three decades. In many cases, predominantly Black or Latino communities that were torn apart by freeway construction a generation or more ago have been dislocated once more by new projects.

The new data show that the U.S. has not entirely moved beyond the racist history of freeway development.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

The latest from Washington

Inflation has seriously damaged several presidencies in the last half century; now, rising prices threaten Biden, Chris Megerian and Erin Logan wrote.

At the international climate conference in Glasgow, the U.S., Britain and 17 other countries agreed to reduce emissions from the shipping industry, which is one of the largest sources of greenhouse gases, Anna Phillips reported. Large container ships use fuel that is dirtier by far than the diesel that powers cars. Ships can also be a major source of air pollution in port cities, including Los Angeles.

Phillips also wrote this look at what the international climate conference has achieved, including pledges to phase out gasoline-powered cars and stop building new coal-fired power plants — and what it hasn’t done.

As Democrats continue to haggle over the details of their big social spending proposal, Jennifer Haberkorn took a look at one of the plan’s largest elements — a major increase in money for early childhood education. The bill would devote about $390 billion over the next 10 years to providing preschool access to all 3- and 4-year-olds. That would mark the largest expansion of free education since high school was added about 100 years ago.

The latest from California

The state’s independent Citizens Redistricting Commission has come up with a draft map of new congressional and legislative districts, and it’s already causing heartburn for a number of incumbent lawmakers, Seema Mehta and John Myers reported.

The new maps may strengthen Latino political clout in California overall, but the most heavily Latino district in the state would be eliminated. The 40th District, represented by Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard, covers parts of East and South L.A. and would be parceled out among neighboring districts, Mehta reported. Roybal-Allard, 80, has raised very little money amid speculation that she has plans to retire next year. The state is losing one congressional district after last year’s census, and the loss was widely expected to come in the Los Angeles area, which has grown more slowly than other parts of the state.

The redrawn boundaries may force some incumbents to run against each other or run in districts that have suddenly become less politically secure. The Central Valley districts of GOP Rep. Devin Nunes of Tulare and Democratic Rep. Josh Harder of Turlock would both be significantly altered, according to redistricting analysts in both parties. Reps. Mike Garcia of Santa Clarita, Michelle Steel of Seal Beach and Darrell Issa of Bonsall would all find their districts becoming less secure.

But there’s a good chance the maps will change again after a two-week public comment period, which began with the commission’s approval of the maps on Wednesday night.

The Biden administration will extend a major homelessness initiative that has allowed Los Angeles and other cities to rent hotel rooms as temporary housing for thousands of people. As Ben Oreskes reported, the administration will extend the program through March. It was slated to expire at the end of the year.

In another development related to homelessness, a group looking to oust Los Angeles City Councilman Mike Bonin says it has submitted more than 39,000 signatures on recall petitions. If the signatures hold up to scrutiny, that would qualify the measure for the ballot. Bonin’s opponents have accused him of failing to take seriously the impact of crime that they say is connected to homeless encampments.

Sign up for our California Politics newsletter to get the best of The Times’ state politics reporting.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.