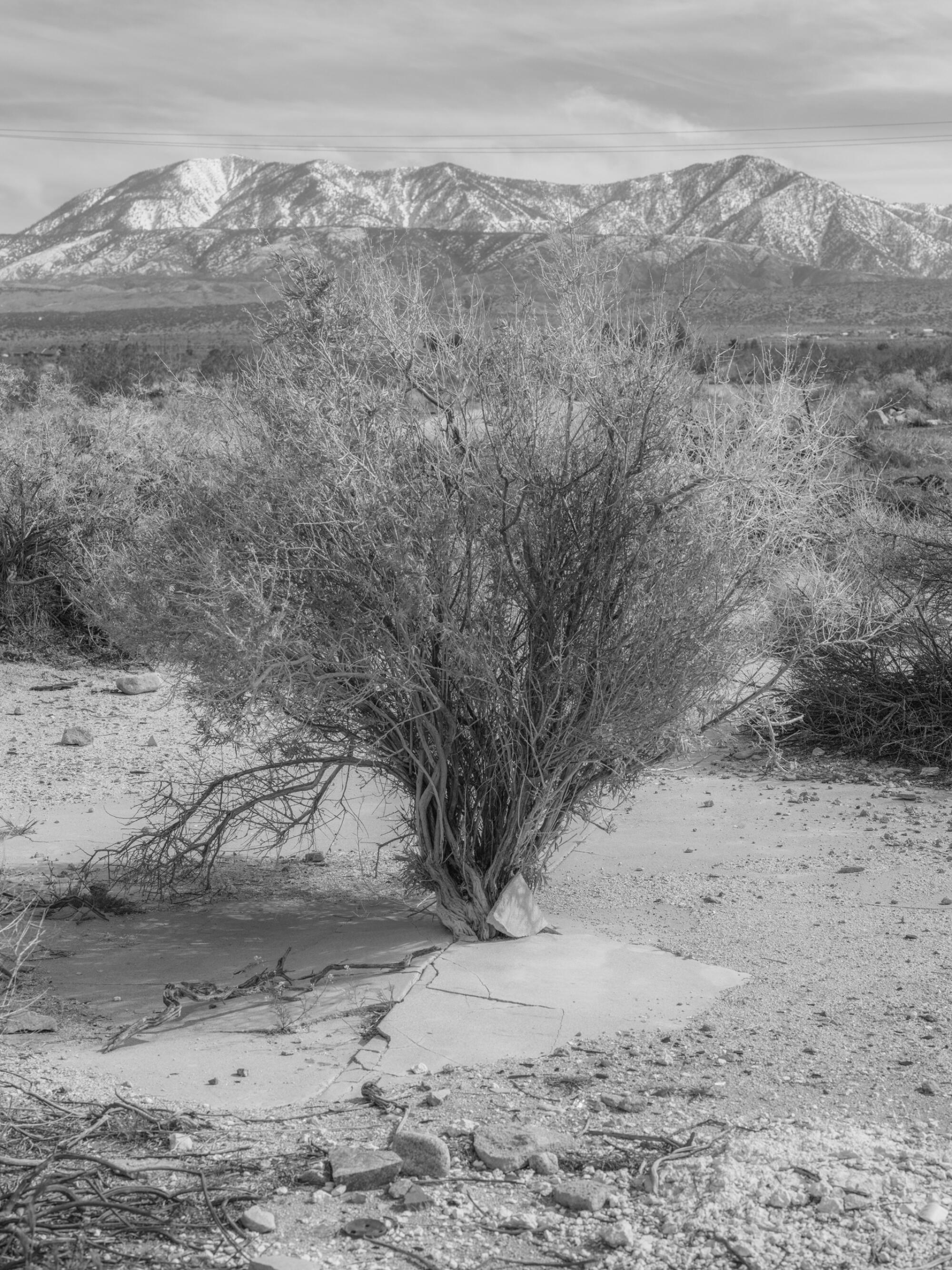

If Los Angeles is a dream factory, then the High Desert is one of its abandoned backlots, where old props are warehoused, waiting to be reused.

Five miles east of Pearblossom, in the southeastern corner of the Antelope Valley, lie the ruins of a town that wanted to change the world. Drive too fast and you might miss them. As you slow to a crawl, a couple of chimney stacks come into view, the final remnants of a large building a few feet from the road’s shoulder. Standing atop its foundations, you will begin to notice rocky outlines through the greasewood and creosote, revealing the outlines of hundreds of structures, including houses, storage tanks and open-air aqueducts, stretching into the distance. The orchards that once lent the area its name are gone, but it is a stunningly beautiful setting. If you look south, you can see the road to the alpine resort of Wrightwood wind its way into the San Gabriels, and if you turn north, you’ll glimpse the purplish Tehachapis at the end of a flat, desert expanse.

At 3,500 feet, the air is clean and sound pollution a distant memory, but the atmosphere is charged. It’s a place of extremes: blazing summers and freezing winters, droughts and floods. In the nearest diner, portraits of John Wayne sit next to shots of Raptors and Nighthawks in mid-flight and a sign above the door reads: “Lockheed Retirees Meet on Tuesdays.” Although there’s no plaque in sight, these ruins are supposedly registered as California Historical Landmark No. 933, and for a brief while, this was the location of the Llano del Rio colony, which styled itself as “the world’s greatest co-operative community.”

It all began on May Day 1914, when a handful of romantics arrived to establish the colony. The valley was more isolated then. The first road connecting it to Los Angeles was built in the 1920s, and the aerospace industry didn’t arrive until the 1940s. Nevertheless, word of mouth spread rapidly throughout L.A.’s progressive circles, luring many curious idealists to the valley. The pitch was simple: Here was the chance to put socialist ideas to the test on fertile soils, taking advantage of the perfect weather and plentiful water. The plan was equally straightforward: Community-owned farms would feed everyone and fund additional industries, including apiaries, hatcheries, canneries, smithies, brickyards and even a film studio. The colony’s numbers grew, peaking at 1,500 in late 1917, but by the following spring, only three years after its founding, “the ultimate socialist city” was dead, sowing confusion and disappointment among its most fervent believers.

Poet Christopher Soto unpacks how the history of policing has shaped and scarred the urban fabric of Los Angeles.

The desire for communal living has always been warmly welcomed by Angelenos, and throughout its history, L.A. County has hosted many intentional communities, from the Christian communards of Pisgah Grande near Simi Valley to the Krotona Theosophists in Beachwood Canyon, as well as the Manson Family’s Spahn Ranch, creating a constellation of dreams and nightmares around the city’s fragmented self. Even today, millennials favor communal living. That widely reported trend might be rooted in financial instability, but it also speaks of a desire to break with past patterns and take further steps toward a more equitable world.

Despite the earnest enthusiasm, the reality is that many of Los Angeles’ utopian experiments have failed over the years. And although it is typically argued that communes often collapse due to infighting, the majority of Californian utopian projects failed for another reason altogether: disputes over water rights.

Llano was a uniquely American sort of commune. Its founder, Job Harriman, was a Lincolnesque preacher and lawyer from Indiana. Heir to the itinerant preachers of the Great Awakenings, he went West in his youth, carrying his potent mix of religious morality and political idealism all the way to the Pacific, where he swapped Christianity for socialism. As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, Harriman began a 15-year quest for public office, which saw him run for governor of California (1898), vice president on Eugene V. Debs’ ticket (1900) and mayor of Los Angeles (1911 and 1913). Harriman came within inches of his goal in 1911, securing close to 40% of the vote before his campaign fell apart when he decided to represent the McNamara brothers, who were later convicted of perpetrating the Los Angeles Times building bombing in 1910. Pushed out of electoral politics by L.A.’s robber-baron elite, Harriman decided he would devote himself to establishing his shining city on the sandy hill.

Backed by private investors, Harriman bought huge tracts of land and sold each new member a share, the proceeds of which were reinvested in operations. Most communes don’t have a board of directors, a secretary or a treasurer, but Llano did. The colony was born as the Mescal Water and Land Co., a corporation that raised capital from banks and issued stock. Each fresh arrival wishing to join the colony would be asked to buy 500 shares at $1 apiece, with the option to buy more, although all shareholders were capped at $2,000. As Harriman put it, this effectively made the colonists “stockholder-employees.”

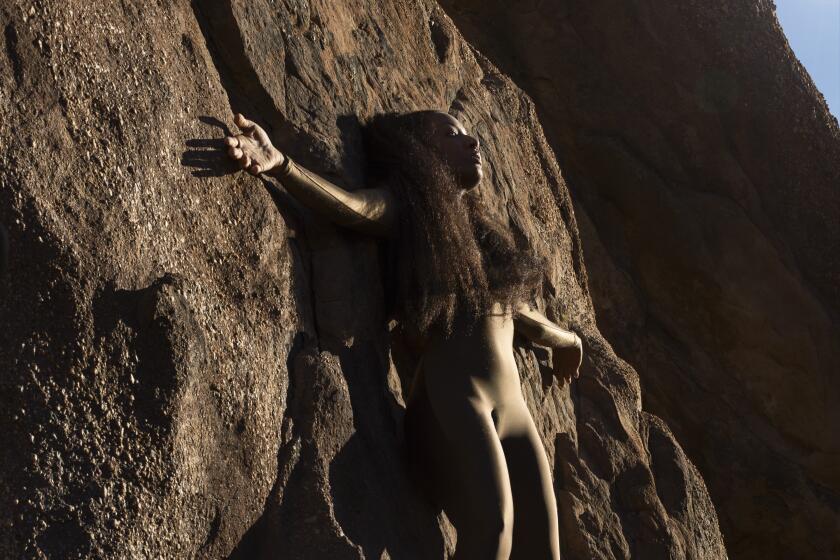

Experimental filmmaker and photographer Sophia Nahli Allison shows you what’s possible when you allow yourself to be led by spirit.

Whatever their designation, photographs from the time show smiling colonists in white overalls with “Llano” sewn across their chests. The colony attracted a wide variety of residents, including farmers, actors, entrepreneurs, musicians and clerks, and by all accounts, life in Llano was lively. Children played outdoors and attended Southern California’s only Montessori schools. Medical care was free, landlords and mortgages didn’t exist, and colonists could attend college tuition-free in exchange for four hours of labor a day. There was a band and a baseball team, and the great hall had a large dance floor. The colonists’ diets were monotonous, with a heavy emphasis on pulses, but a sense of shared purpose electrified the air.

Many of the children born there would carry memories of the colony for the rest of their lives, and some would leave significant legacies behind: the dancer Bella Lewitzky was born in Llano, and if you’ve ever stumbled across a Modernist low-income housing unit somewhere in the city, it was probably modeled after ideas laid out by Gregory Ain, who spent his early years in Llano and later designed Avenel Homes in Silver Lake, among other projects.

Harriman had his own starry-eyed architectural aspirations when he called on Alice Constance Austin, a radical feminist architect, to design a plan for Llano. Austin’s drawings show a circular city on a radial grid with kitchenless houses, freeing women from domestic servitude. All houses were to be connected to communal daycare areas via underground passages wide enough for electric cars, reducing congestion on the surface. Borrowing from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern traditions, Austin planned for houses made of solid concrete, with thick walls to keep them cool, and flat roofs where urban gardens would be planted. Although she built a scale model of her “city of the future,” she never got to put her ideas into practice. Unbeknownst to Austin, Llano’s experiment was already nearing its end.

An exhibition at REDCAT is built on Octavia E. Butler’s “Parable of the Sower.” Its creator, American Artist, talks with Tananarive Due.

The colony’s chief water source, Big Rock Creek, couldn’t satisfy the demands of both Llano and nearby cattle ranches, and so the ranchers sued, and the colony lost the rights. Harriman was also betrayed by some collaborators who speculated on Llano stock and defrauded investors. Unfortunately, it was obvious that Llano Del Rio had failed to live up to its ideals from the very get-go. An unsigned advertisement in the Western Comrade, the colony’s in-house publication, read as follows: “Only Caucasians are admitted. We have had applications from Negroes, Hindus, Mongolians and Malays. The rejection of these applications are not due to race prejudice but because it is not deemed expedient to mix races in these communities.” The ad, ironically titled “The Gateway to Freedom Through Co-operative Action,” was reprinted in several issues. Utopia was the exclusive preserve of white people.

Although by 1917 colonists tended over 2,000 acres of alfalfa, corn and grains, thereby growing 90% of Llano’s food only two years after it was established, the community’s size quickly outgrew what farming conditions could support. By March 1918, the fantasy of Llano died of thirst, owing to a perfect storm of decreased rainfall and vastly increased irrigation needs. Realizing the location he had chosen could not support stable foundations for his increasingly ambitious project, Harriman and his collaborators began laying plans to relocate the colony to a new site in Louisiana. The end came quickly and unceremoniously. Homes were abandoned, lawsuits filed and accusatory fingers wagged in all directions. Neighbors ransacked the colony for every brick, plank and nail, and the desert slowly reclaimed Llano.

Twenty-three years later, Aldous Huxley, one of the era’s greatest novelists, left his apartment in Santa Monica in the wake of Pearl Harbor and moved to a 40-acre ranch across the road from the colony’s ruins. Huxley spent his time there adapting Charlotte Brontë’s “Jane Eyre” for 20th Century Fox and meditating on the lessons of the Llano experiment. These thoughts bore fruit in his essay “Ozymandias, the Desert Utopia That Failed,” named after Shelley’s poem about a traveler in the desert who chances across a half-buried statue whose inscription warns that all human efforts are doomed to oblivion. “All that the history of Llano teaches,” Huxley wrote, “is a series of Don’ts. Don’t pin your faith on a water supply, which, for half the time, isn’t there. Don’t settle a thousand people on territory which cannot possibly support more than a hundred.”

Llano is not the only utopian experiment that died of thirst. Allensworth, an hour north of Bakersfield, was another. Founded in 1908 by Lt. Col. Allen Allensworth (1842–1914), who was born into slavery in Kentucky and served as an army chaplain during the Civil War, it was the first community in California entirely built and run by and for African Americans. Allensworth aimed to become the “Tuskegee of the West,” and if white farmers and the water company hadn’t conspired against them by denying their requests for wells and contaminating their supply, the community might have achieved its aims.

Utopia is a thirsty dream, especially here in California, where water shapes not only our physical realities, but our dreams and visions of the future. The idea of an equitable, ecologically balanced society encapsulated by the word “utopia” (meaning “no place”) stands at sharp odds with the unstoppable metastasis of real estate capitalism and its speculative suburbanization of all available space on this planet. In fact, of the two ideas, it is the latter and its belief in the power of endlessly subdividable plenty that is truly utopian, for there is no rational basis to believe in its long-term sustainability.

In her final article for the Western Comrade, Austin opined on the life cycle of the modern city: “If the money that is wasted on this constant process of tearing down and rebuilding were put into carefully planned permanent construction, there would be plenty of money to house the poor as comfortably, if not as extravagantly, as the rich. We may yet learn that it is more blessed to know that our neighbor is not suffering want, than to elaborate luxurious ‘cottages’ and ‘bungalows’ for ourselves.” Meanwhile, Job Harriman’s call to “build a city and make homes for many a homeless family” still rings urgently necessary, especially in Los Angeles, where poverty is compounded by the same environmental apartheid that murdered Allensworth’s dream.

This conversation between activist Theo Henderson and scholar Ananya Roy foregrounds the endeavors and collaborations that seek to challenge such erasure.

Visiting these real-life, would-be utopias is a necessary education for anyone interested in how human idealism often accounted for everything except for the natural environment around it. Don’t wait too long. Some may not survive the twin forces of environmental devastation and property development much longer. Earlier this year, Allensworth endured record floods, while the dusty, forlorn site of Llano remains sandwiched between expansion plans for the Pearblossom Highway, on whose edge it sits, and the encroaching suburban sprawl of Palmdale and Lancaster. You don’t need to look very far to see what Los Angeles might look like in the not-so-distant future.