This story is part of Image issue 8, “Deserted,” a supercharged experience of becoming and spiritual renewal. Enjoy the trip! (Wink, wink.) See the full package here.

I haven’t really even told this story to anyone. I still do have dreams of flight.

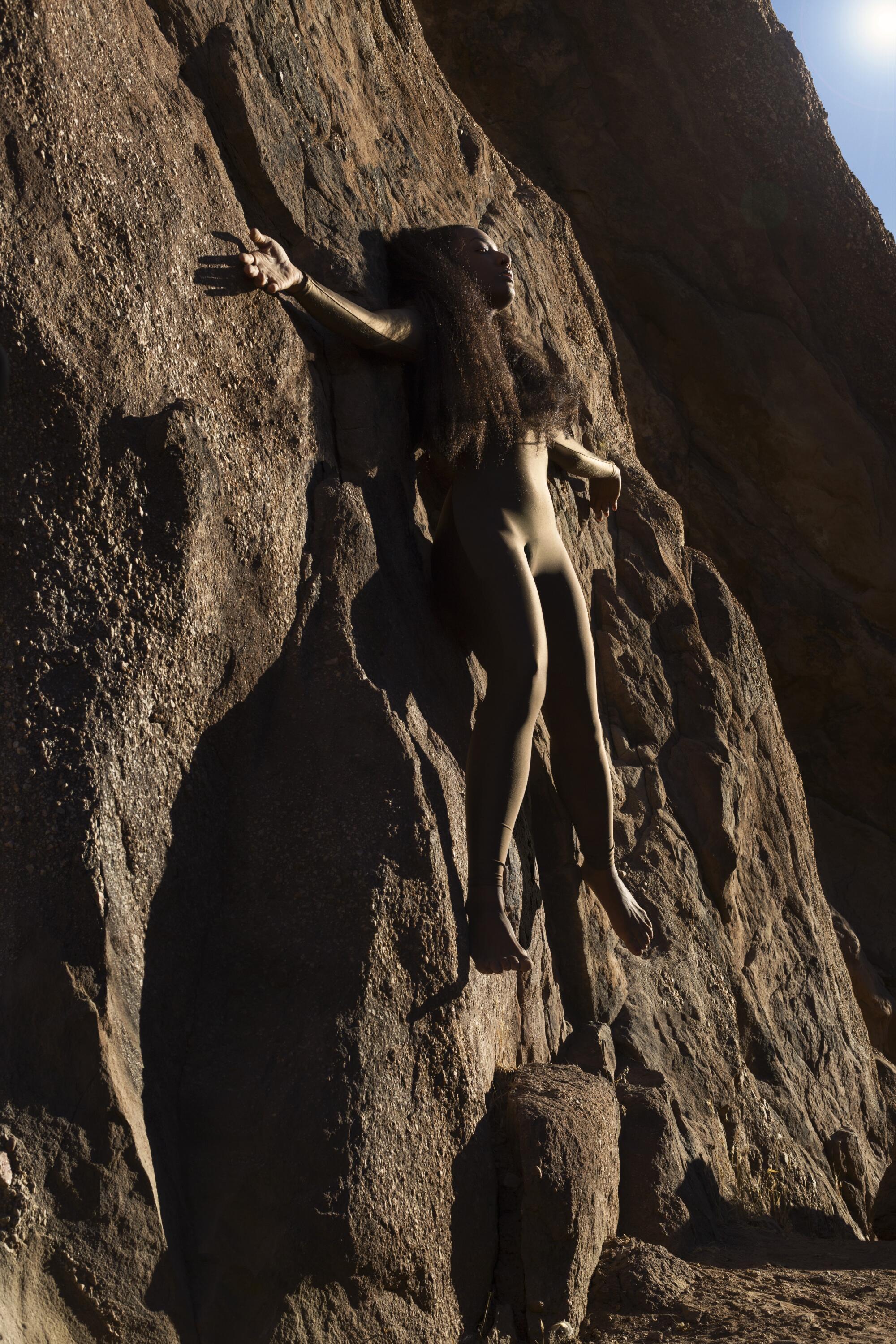

I don’t think I would have had that language as a kid to describe how it happened exactly. It was more about a sensation. A mental concept. I had to be concentrated and focused. I had to be in this deep meditative state. The moment I lost focus, it would completely disappear. It was like an astral projection, you know. Our sphere of being able to leave our body for some time. I would just be able to create this sensation of my bed completely taking off the floor.

Me, just flying.

It’s not like that anymore. There was an age when it completely stopped. And I was never able to do that again. Still, I remember how my dreams of flight were how I discovered that I could exist in a way that I wasn’t allowed to in my everyday life. Dreams felt like this place where I could be safe, where I could be who I wanted to be, where I could be my full self. I could remove all these barriers that kept me confined and be as free and as adventurous as I wanted to be.

In my dreams, I’m able to fly away when I am in a situation that I need to get out of, a situation that does not feel safe, that I don’t enjoy. When I don’t want to be around, I am able to completely release my body and fly away. That’s what I’ve discovered in dreams. How to liberate myself. How to free myself.

I think it probably was hearing stories of flying as a young girl. Knowing the story of flying Africans, being familiar with them through Toni Morrison and Virginia Hamilton. Octavia Butler starts off “Parable of the Sower” with the lead character, Lauren, talking about herself flying in dreams. It made me so happy to discover that whenever a Black woman talked about flight, she was using flight as a coded language for self-liberation. Realizing it was a conversation woke me up in a way.

Inside issue 8: ‘Deserted’

Kenturah Davis and Alice Smith have a supercharged self-care retreat.

Justin Torres remembers those visits to the clothing-optional hotels in Palm Springs.

Julissa James explores why so many people head to Joshua Tree to do shrooms.

Dave Schilling gets to the bottom of why chest hair is the desert’s No. 1 accessory of choice.

How do I do it? How do I fly? Toni Cade Bambara once told fellow writer Akasha Gloria Hull: “It’s only air.” Honestly, I don’t tell anyone how I do it. I’ll say my body is the site of memory. I’m allowing myself to be led by spirit. I’m a conduit.

::

I‘ve often found that adding little bits and pieces of magic in my own life is really healing for me. It’s how I envision the world. It’s how I see. I want spirit to be an element of my documentary work because there is no tangible proof that this type of realm can exist to some people. Black folks, Black woman, Black queer folks — in our oral history, we have always incorporated these elements of spirit, these elements of radical imagination. As the filmmaker, I always want these elements to be a part of the story.

I am curious what the spiritual realm looks like. I just want people to question:

What does it look like to exist in multiple realms at once?

What happens when we don’t have evidence of the story?

How do we reimagine what that story looks like?

How do we reimagine what the spiritual archive is?

How do we engage with ancestors?

How do we engage with memories?

How do we engage with our dreams?

What does the nontangible look like?

What does healing look like and feel like?

How do we allow our imagination to be expansive?

Am I in a dream or am I in reality?

If it feels like a dream, why can’t it be a truth as well?

I consider myself an experimental filmmaker and photographer because I am always exploring how to blur the lines between reality and fiction. In a lot of my film work, I want to break down conventionality and explore new ways to tell stories. What does that moment look like between waking and sleeping? I always want my work to feel a bit ethereal. It is a process of conjuring. It is taking moments of the everyday, of the mundane, and finding those magical and spiritual elements that exist and live around us.

I’m really inspired by the work of writer Zora Neale Hurston, who often blended these lines — Here’s folklore. Here’s our truth. Here’s my history: This is what I’m going to withhold; this is what I’m going to tell. I grew up hearing a lot of folklore and realized that it was something that spoke to me deeply. It spoke to who I was in my private moments. It spoke to how my imagination would run wild, what things I wished were true, what things I wished I could experience. As a filmmaker or a photographer, I don’t have to compartmentalize what people think is truth and what people think is folklore. I can let both exist in the real world with us. It’s not like I’m at all altering the truth — the recorded truth is there. But I’m also adding a new truth to the archive that hasn’t been there before.

I don’t know how to do it any other way.

::

I remember when I was starting off. I taught myself photography. I went to school to study photojournalism as an undergrad at Columbia College Chicago, and then I studied documentary filmmaking in grad school at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I found myself trying to emulate what I saw everyone else doing. This is how documentary should exist, I thought. This is what qualifies as photojournalism. I always wanted to be an artist, but I just didn’t feel I had the time or the proper training to call myself one. It was safer to call myself a documentarian, or a visual journalist, because I didn’t have the qualifications to be considered an artist. That was my own work concept that I had to unlearn and grow out of.

I realized I was not a photojournalist when I was doing an internship. I was sitting in my car, deciding if I should take time off from grad school, move back to L.A. and take this job working in film. I had a panic attack. I was like, I do not enjoy photojournalism. There is no freedom. It’s rooted in the white gaze. I am really surrounded by white supremacist ideology. I really need to be free from this.

In documentary, you’re supposed to remain objective, but objectivity is not something I really believe in. As a Black, queer woman, there’s no way I can disconnect myself from my experience and the experiences of those who look like me and who move through the world like me. In two of my documentary projects — “A Love Song for Latasha” and “Eyes on the Prize: Hallowed Ground” — I started to understand that I needed to put myself into the work, both physically and spiritually. It’s so important to make sure that the way in which I tell stories through documentaries is authentic. As a Black woman, it’s crucial that I’m archived.

I grew up around artists in Leimert Park and Jefferson Park. My dad was a musician; my mom, a storyteller. My mom would perform in Leimert — at the library, at museums and schools — and I would join her and her group of storytellers every now and then. Alice Walker, in her seminal essay “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens,” asked: “What did it mean for a Black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? It is a question with an answer cruel enough to stop the blood.” So often Black women don’t have the resources, the support, the agency, the freedom, to be an artist. My mom made all of her own props and costumes. I often witnessed her in the house, performing and practicing. It was so inspiring to me to see a Black woman keeping art alive for herself.

A lot of her stories primarily were stories of the diaspora, stories of the Black South and Black life, stories of her memories from childhood. Primarily, it was a lot of folklore. I remember learning “Anansi the Spider,” which enchanted me as a young girl.

My mother opened up a world of folklore, an oral tradition, that piqued my curiosity. One such story I learned was Virginia Hamilton’s “The People Could Fly.” “The People Could Fly” is so digestible for a story that’s actually rooted in trauma. I love how it depicts some Black folks who are left on the plantation and others who are able to fly away. Just because a person is Black doesn’t mean they can fly. That’s really important to note — what does it mean to fly? Well, you have to wake up to a certain consciousness. There’s a form of rebirth in it; there’s a form of We are going to reclaim this agency over our life. I love how it’s presented for Black children to understand this folklore, to understand this possibility and this history. That was my earliest understanding of storytelling — that there are these worlds that exist that are not documented as our waking world, but there is a truth contained in those worlds.

::

Summer 2020: My girlfriend and I drove across the country from North Carolina to L.A. I had been living in North Carolina for a couple of years and was extremely homesick. And we were like, “Let’s go back.” On the drive, I remember seeing the landscape change. The desert, the mountains — I started getting the feeling, This is my return home.

The desert represents rebirth. It’s a landscape that you don’t expect to see be fertile. You don’t expect to see things grow from it. But that’s what’s so beautiful. It’s not dead. There’s so much life here. I always think, What are these Joshua trees saying? I wonder about these voices — the sounds the mountains of the desert make, the spirits that exist. I love how quiet the desert is. The wind has such a personality.

A weekend of self-care in the desert with Alice Smith gets supercharged thanks to a lunar eclipse and a trip to the sound bath.

I like to speak to the universe when I’m in the desert. I like to just speak out loud. No one can hear you. No one. I can just say the words I need to say. I talk to myself. I talk to my ancestors. I love to collect rocks and dirt. I love to have a piece of that. To know that I was here. To know that was real.

You can leave your secrets in the desert. Whatever you give to the desert — when you come back, it’s going to be there. The energy you brought with you. The collections of memories of each experience. Whenever I return to the desert, I think about the last time I was there or the time before that.

The desert just keeps going on and on and on, and there’s no barrier, there’s nothing stopping you. Zora was always talking about horizons and I love that about the desert. I often have to remind myself that there is so much life beyond what I can see, what my present is. The desert allows me to feel small, but it also allows me to know that I have a purpose. When I allow myself to feel and see the vastness of the universe, I am able as an artist to reconnect with my purpose.

When I’m in the desert, time is nonexistent. Or rather, when I’m in the desert, I feel connected to time in a way that I don’t get to experience often. When I’m in L.A., I feel time always. And I’ve been really working at having a more collaborative relationship with, and a better understanding of, time.

Time might not feel the same in the desert. But you see traces of it everywhere. You witness the shadows that the sun casts; you see the slightest changes in light — tweaks to sunrise, sunset, midday. You think: I can’t believe I get to witness this beauty. I can’t believe I get to look at and be near these mountains that have such a history. My last trip to Joshua Tree, the sunset was so divine that I didn’t want it to end.

In the vastness of the desert, everything feels aligned. Everything feels right in the cosmos and right within myself. The desert opens up a psychic space for me to be honest about my deepest dreams, to just daydream about things that maybe I don’t even think are possible. At that moment, it feels like there are no limitations. You can imagine anything. There are no distractions. It’s really healing for Black folks to experience a place where there are no barriers. It feels like nothing can stop you.

There are so many different ways to fly in the desert. How you choose to fly is a conversation between you and air.

Sophia Nahli Allison is an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker and photographer. As a Black queer radical dreamer, she reimagines the archives by excavating hidden truths. A meditation of the spirit, her work conjures ancestral memories to explore the intersection of fiction and nonfiction storytelling. She is a South Central L.A. native.