ALLENSWORTH, Calif. — Last week, when it rained for days and floodwaters poured onto roads, the people of Allensworth grabbed shovels and revved up tractors.

The makeshift barriers they built with sandbags, gravel and loose sand kept the water back.

Now, the town of nearly 600 people northwest of Bakersfield faces another threat — a broken levee, along with yet another storm expected to hit in a few days.

On Saturday morning, the residents were back at work, shoveling sand onto a 3-foot high berm.

Allensworth, the state’s first town to be founded by Black Americans, is now a predominantly Latino community. Some residents work on nearby farms, planting and harvesting almonds, pistachios, grapes and pomegranates.

Local leaders say they need help from county, state and local officials to protect their town.

“It is becoming a major crisis for our community,” said Kayode Kadara, 69, who has been working with neighbors to defend against the floodwaters. “We have a lot of concerned people in this community. And we all rally to help each other.”

The low-lying unincorporated community lies in the Tulare Lake watershed, which was drained for agriculture in the early 1900s. The latest storms have sent floodwater coursing through canals and ditches and flowing across farmland toward the old lake bottom.

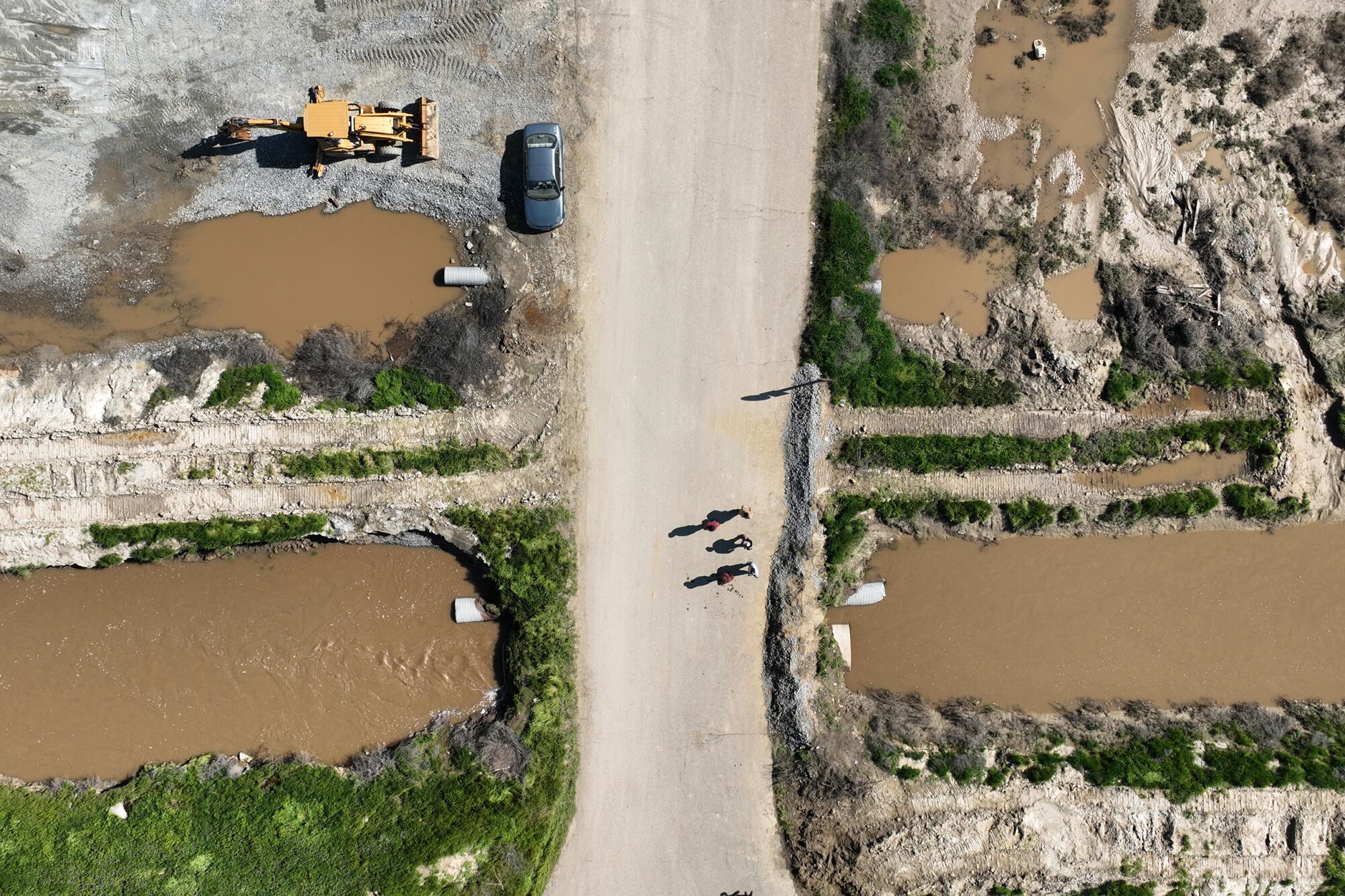

On Saturday, a helicopter flew over the broken levee and was dropping loads of sand to plug it, while a crew was using machinery to help close the leak, said Jack Mitchell, head of the Deer Creek Flood Control District.

He said the levee was almost fully repaired but that flooding was still a huge concern.

Mitchell said he believes the levee breach was caused by someone intentionally cutting through the earthen barrier with machinery.

“They did it with a backhoe with a big skip-loader. We tracked it down,” Mitchell said. “We know who’s done it.”

Mitchell said he hopes the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers or other authorities will come in to “take charge” and help the area “start getting rid of this floodwater.”

“We need some help from higher up because out of another creek, the water is just getting there, and it’s going to hit us hard,” he said.

Some landowners have been trying to keep floodwaters off their acreage, Mitchell said, including one that used a large piece of equipment to block a channel.

“They just don’t want to give up any ground, but they’d rather flood everywhere except where it’s supposed to go,” Mitchell said.

More than a dozen residents stood talking beside a runoff-swollen ditch. Beside them was a gravel berm they had scrambled to build two days before near the entrance to Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park.

In the distance, a red emergency helicopter flew back and forth, apparently dropping loads of sand to repair the broken levee.

The churning brown water had sunk a few feet below the berm, but residents said they are worried they might have to evacuate when the next surge of floodwater comes. They said a couple of families have already packed up and left low-lying homes.

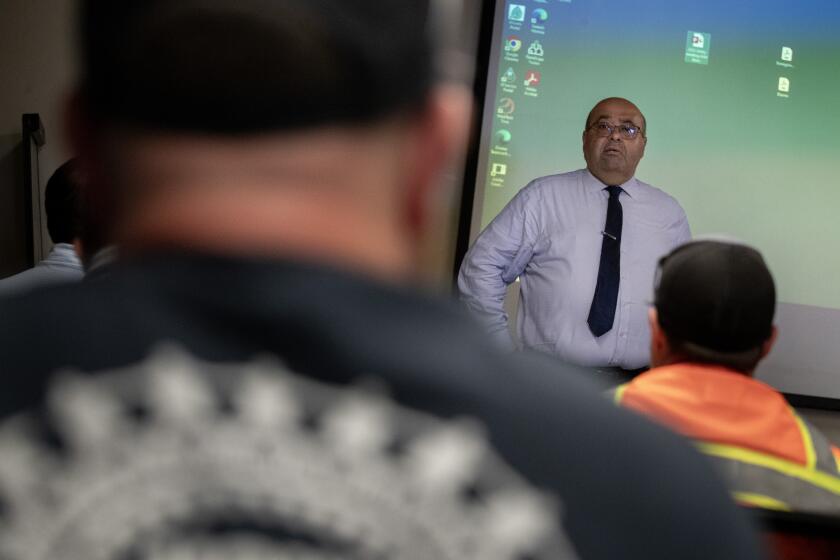

Kadara’s son, Tekoah, said more than 100 residents met at the elementary school Friday night to discuss plans for preventing disaster.

A California Historic Park commemorates life in Allensworth, a Central Valley town founded after the Civil War where Black residents could prosper.

“We’re just talking about how we can save our community, because nobody is coming to help us,” said Kadara, 41, executive director of the Allensworth Community Development Corp.

“We need temporary armoring right now,” Kadara said. “We need to stop the water from coming into the town.”

Floodwaters from the White River have been coursing past the town, and Kadara said people are also concerned about water spilling from Lake Success.

When residents saw water surging toward the community on Thursday, they said, they used sandbags, rocks and plywood to plug the flow through two culverts along Highway 43 beside the BNSF train tracks.

“We actually did a good job of temporarily solving a problem. But for whatever reason, the railroad unblocked it,” Kadara said.

Kayode Kadara said BNSF Railway sent contractors who came with machinery and removed the sandbags and plywood.

He said he’s concerned that the community’s residents haven’t gotten the help they need to protect themselves.

“They wouldn’t allow this water to come into a white town,” Kadara said, standing beside the flood-swollen ditch, where water flowed through the culvert under the road.

Residents said that when they were initially working to plug the culvert, they had taken some rocks that were piled beside the railroad tracks, but a crew told them to stop. So they brought their own sandbags and plywood to erect the barriers.

Days after the rain stopped, communities across Central California, including Porterville and Visalia, are still under evacuation orders and flood warnings.

Lena Kent, a spokesperson for BNSF, said that the residents had come onto railroad property and that their actions had put the railway infrastructure at risk. “That wasn’t the right approach,” Kent said.

She said railway officials were concerned that plugging the culverts would send water scouring the railway property, “and we could have had a track give way there.”

“I just think that they put a lot of people in danger by doing what they did that evening,” Kent said. “I completely sympathize and understand what they’re trying to do, but perhaps they should focus on protecting, sandbagging around their property.”

She said BNSF is open to hearing ideas from the community and is also working with the county and the state to protect the railway infrastructure.

“It slowed water flow to their tracks, for heaven’s sake. How could that be dangerous?” Kadara said.

Kadara, a retired regional facilities director for the U.S. Postal Service, works as an adviser with a local nonprofit called the Allensworth Progressive Assn., which leads community projects.

He said Allensworth urgently needs help from county, state and local flood-control officials. Farm landowners also need to be part of the discussion, so they can help direct floodwaters away from the community, he said.

The community has a long history of coping with floodwaters.

Jose “Chepo” Gonzales, 50, said he remembers the flooding in 1979, when he was 7.

His father wore rubber boots and waded through the water, lifting him up to join others on the bed of a dump truck.

His father had stayed behind to try to protect their home, ramming an old Plymouth to stop a leak in the canal bank, where men piled rocks and dirt, Gonzales recalled.

Gonzales said those repairs are still visible as a bulge in the levee.

“I got to do like my dad did then,” said Gonzales, who moved sand with a small tractor to help build a berm.

He said he planned to load his cattle onto a trailer and take them to a sister’s house on higher ground. Other people in the community have goats, pigs and chickens.

Raymond Strong, a resident who once played in the NFL for the Atlanta Falcons, also remembers 1979, when his grandfather died in the floodwaters along with another man.

“It’s real scary,” Strong said. “If the water really comes, it’s going to uproot people.”

He said he plans to stay, and he hopes the town will get the resources it needs.

“Thank God that we have our neighbors,” Strong said. “It’s amazing to see the way they are coming together.”

As the residents stood talking by the flowing ditch under a clear sky, Kayode Kadara pointed to the snowcapped Sierra Nevada in the distance.

In the spring, the historically deep snow will melt and come rushing down to the valley floor.

“Once it gets warmer and starts flowing, we have a major challenge on our hands,” he said. “We’re looking at two to three months more of what we’re facing right now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.