This story is part of Image Issue 14, “Elevation,” where we examine beauty as a state of being, a process of realization. Read the whole issue here.

I was just a boy with the crooked hairline.

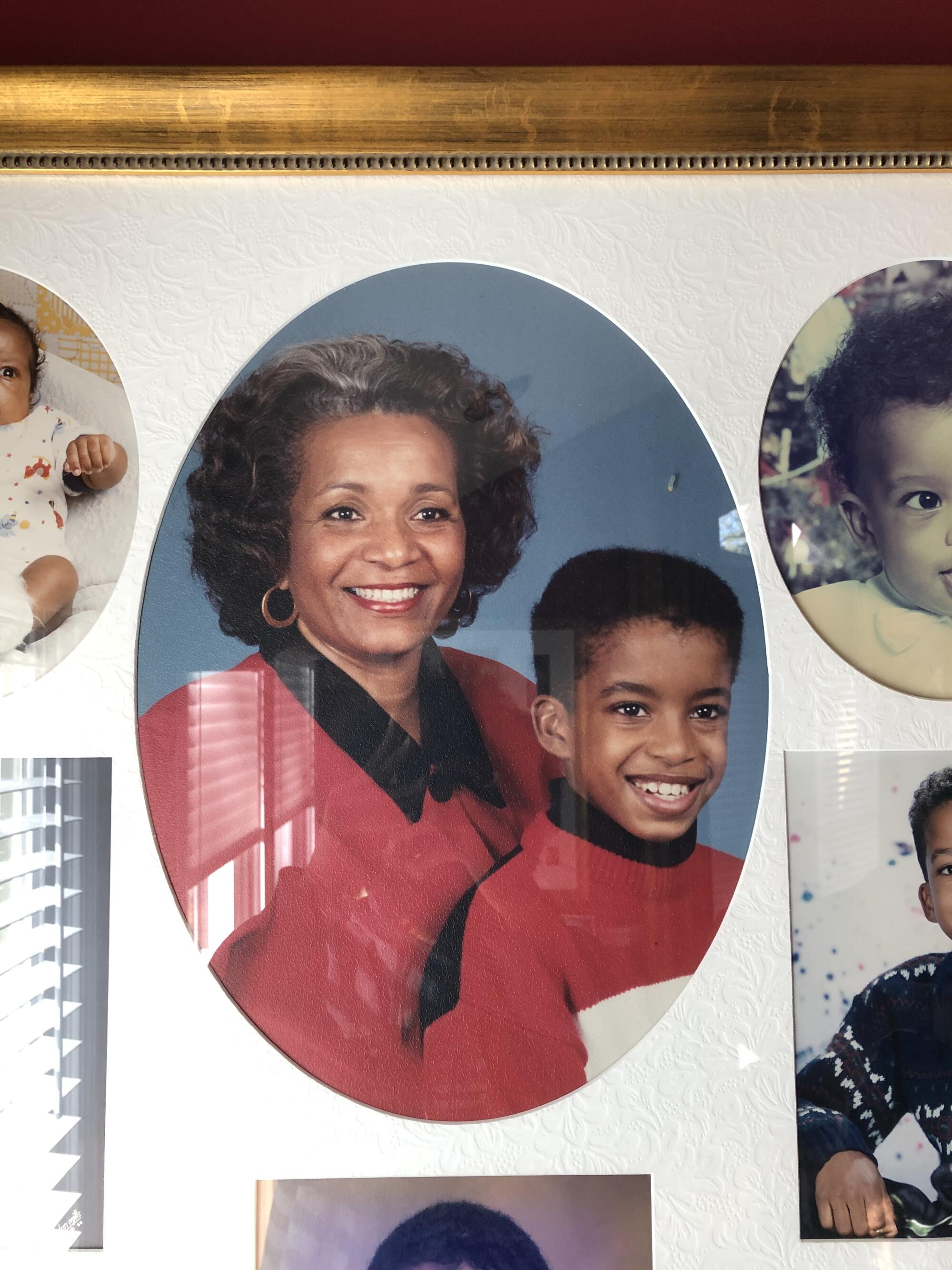

To say that my younger years were without shape-ups, line-ups and edge-ups would be misinformation. There was some curved precision buzzing that made its way to the nape of my neck, as well as trimmed right angles around my ears and mini-sideburns. But for the most part, it was the curls that covered my head — not the line atop my forehead — that were in charge of the framing of my face.

The look, as I remember it, was all natural. And, because boys can be cruel and girls can give glares, to some too natural. My hairline wasn’t reckless, but it did wind. Starting at one ear, it’d veer up straight for a while, then jut in, run a route back, making it to my forehead, where it would parkour to the other side and then semi-symmetrically do the same thing, headed to my other ear. If I turned my head to the left, the path of my hair looked like Florida. Miami down by my ear, Tampa by my temple, and my hairline resembling the panhandle running up against the Gulf of Mexico.

When Rembert Browne is overtaken by the sudden onset of strange ailments, all he knows is that something’s off. Is it anxiety? A serious illness? He’s not sure.

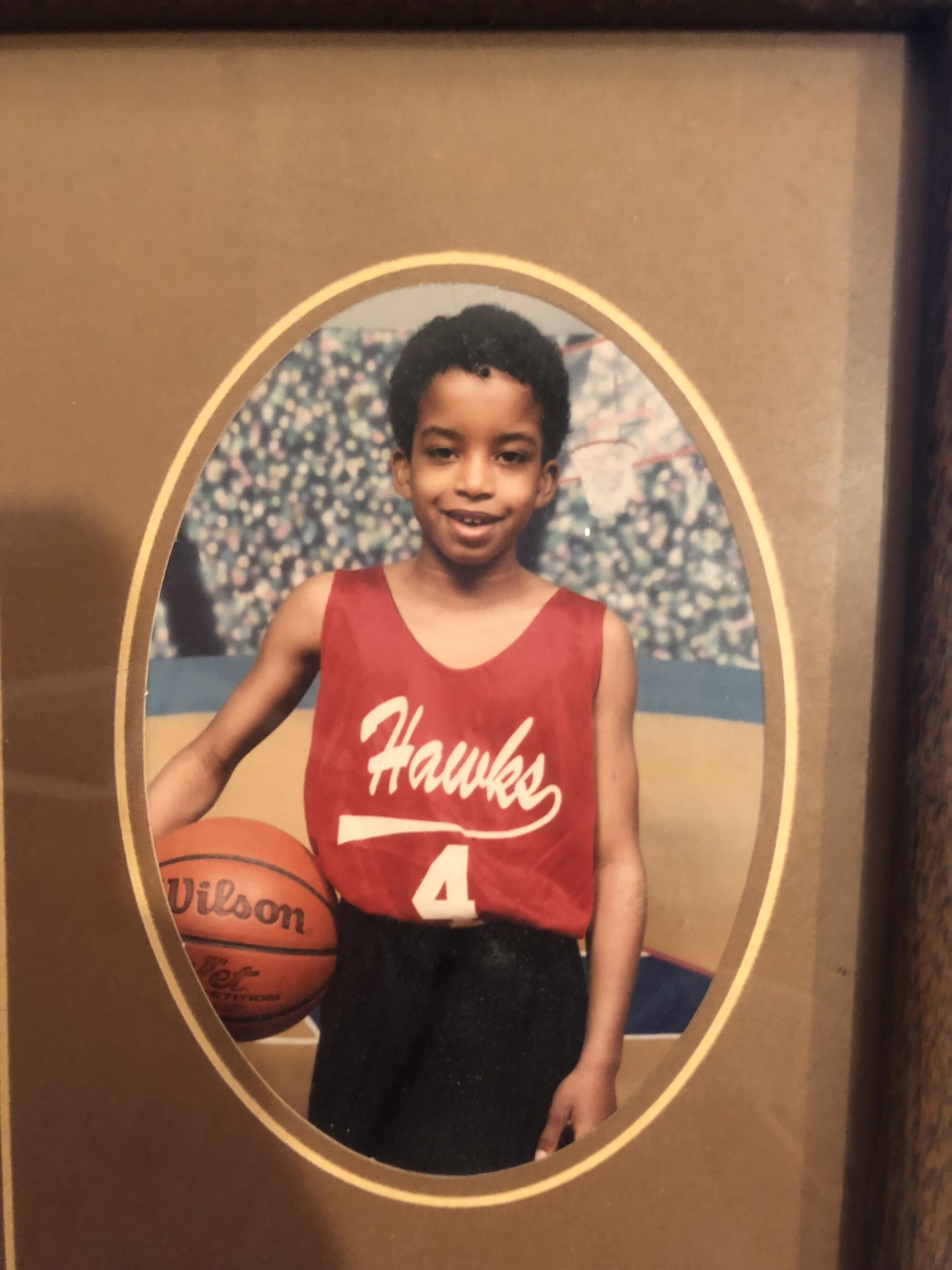

I didn’t mind it. Wasn’t really thinking about it. At the time, I cared about hooping, playing tennis and making my mother happy. She was at the helm when it came to my hair, and with her in the driver’s seat (both in the house and at the barbershop, giving instructions), she was good, so I was good. Also, to be fair, everyone growing up had something that would get them made fun of. “Funny name + funny hair” was no match for “He fast, tho, pick him.”

And then, one day, the barber chopped off my widow’s peak. As they say, nothing was the same.

Sparks was a Black barbershop, half a mile from my first home, in Southwest Atlanta. It sat at a crucial crossroads in Black Atlanta, where Cascade Road became Ralph David Abernathy Boulevard. For me, the 11 miles that the two streets covered felt like traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Cairo to Cape Town. It was my entire world. And I didn’t feel like I was missing out on a thing because most tasks, experiences, firsts happened on — or a few turns off — this one street.

The barbershop sat at more than just a name-change crossroads. Abernathy felt more working-class, with apartment complexes and single-family homes. Ours was on the Abernathy side, a brick house on the corner with a front porch and a backyard. Cascade had those, too, but also the biggest homes I’d ever seen. It was also where we’d drive to do our trick-or-treating, trying to get candy from one of the Kris Kross Chrises or megachurch pastor Creflo Dollar (when the gates leading to his mansion closed, there was a dollar sign on each, just to let you know).

Up and down that stretch my mother and I went, single parent and only child, her very purposefully showing me that our people contained multitudes. You spent time around people with different money than you, who worshiped at a different type of place than you, who went to a different type of school than you. Blackness felt so expansive when we were together on that stretch during my childhood. And how could it not? The prism through which I saw the world was built on one defining characteristic: Throughout my childhood, there was not a white person in sight.

Everyone was Black.

My mother and I showed up to Sparks in the daytime, just a normal trip to the shop. Even after moving out of the neighborhood, we still were loyal, in large part because one of the barbers was the son of my mother’s best friend.

Being the self-aware woman that she is, my mother decided to leave once I sat down on that throne of the barber chair. I’d been going for a while, fully under her supervision, but I was growing up. So she went across the street to Kroger. I still don’t know if she had anything to buy, but she must have figured I needed time in that Black-Man-Only space to continue filling the voids that she couldn’t fully fill, the gaps in my cultural education.

Half an hour later, she returned to see her son, curls buzzed off, hairline so straight you could have used me to hang a painting. My mother was furious. Having family behind the chair backfired because, as my barber and as a Black man, he was trying to fill that void in his own way.

I witnessed what was happening and didn’t protest. I didn’t know if I liked how I looked, but it didn’t matter; I assumed it was how I was supposed to look — like Boy #6 on the barbershop chart. I felt connected to the rest of the men in the room, and the ones that I’d see (and would see me) once I left.

For a few weeks, I was a boy with a straight hairline.

I never went to Sparks again.

Despite not growing up with a man in the house, I had an amazing childhood. That was because my mother was deliberate in making sure I, her Black son, experienced all of the cultural touch points that I needed to thrive and survive. Education was at the top. Learning how to s—-talk and defend myself with my words was a must. Understanding and appreciating the Black church was up there, just like having a reliable jump shot and being able to take a hard foul and keep playing.

So much of being young and Black for me was simply listening. Soaking up my surroundings. Studying all of the characters. Watching the way people dressed, absorbing the way people joked, got clowned, handled being the centerpiece of a roast. I was a quiet kid, I didn’t contribute much early on, but that was fine — I needed time to figure out how to fit in, how to shine, how to live.

More stories from Elevation

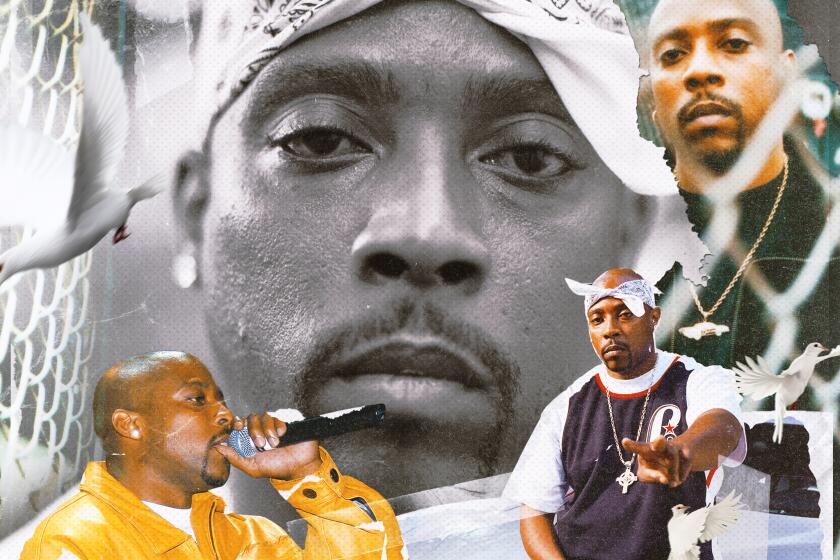

Jason Parham revisits the Smokey Robinson of hip-hop, Nate Dogg

Rikkí Wright unpacks the beauty routine as a metaphor

Devan Díaz takes on tweezing as self-care in our warped times

Dave Schilling investigates why the mullet is the haircut that refuses to die

The state of L.A. beauty in one zine

Traditionally, all of those things happened at the barbershop. But after the barber’s heavy sleight of hand, his creation of a hairline, my mother felt it was time for a reset. What followed was my first secret source of shame. One of those “the homies can never know about this” moments. For the majority of my preteen and teenage years, I was a regular at Supercuts, in Black-ass Atlanta, Georgia.

We didn’t really talk about it, my mother and I. There was no beef, we were both complicit. But no one felt great about it. For her, perhaps, things were just moving a bit too fast. My world was expanding: Soon, I was in a new, predominantly white school on the opposite side of town. While thrilled with my new education, my mother — hoping to mold me into the vision of what her Black boy should be — went out of her way to keep me grounded in my neighborhood, my people. Once some Black kids in Atlanta went to white private schools, in white neighborhoods, their entire lives began to shift. This was one of her most significant concerns, me forgetting where I came from, so we took a different path — with the one exception of my haircuts.

So much of being young and Black for me was simply listening. Soaking up my surroundings. Studying all of the characters.

— Rembert Browne

She found other places for me to get molded as my hair went back to her liking under the oversight of the national chain salon (going there felt akin to going to a KFC, when a Popeyes is right there). Tight, controlled curls with a little height became my look. Sideburns were slowly evolving but didn’t go past my ear. I had a baby face, but the jokes about “a little dirt on top of my lip” were beginning to pop up.

Even into high school, when I started to actually care about how I looked, I didn’t consider my hair a variable. There had only been two realities, Sparks or Supercuts, which left me with one option. So all of my energy of trying to look cool, more mature, something beyond “cute” went into clothes. Fitted caps. Clean Air Force 1s. Big, layered tees and even bigger jerseys. You know, fashion.

Once a mustache began making an appearance, however, my relationship with my face began to change. I was raised to believe that a Black man should always have a mustache, and it felt like my decision to maintain it. Trimming it with those little scissors became my first foray into grooming — and into caring. The afternoon of my senior prom, piled into a bathroom with my guys, a friend’s dad showed me how to shave, a rite of passage I missed not having a father. He knew that void, and it felt special.

With a bare lip, dressed like a King of Comedy, I hit the Atlanta streets. A week later when those photos got developed, I hid how much I hated how I looked. I wanted to shave, because that’s a thing men did, but it was then I realized how that mustache made me feel like someone en route to being a Black man. The hard part, however, was that the older I got and the more present that mustache became, the more I became a spitting image of my father, whose name was also Rembert. That realization came from my mother, but I heard the comparison more so from people in the city — those who knew him way back when in Atlanta. It wasn’t a connection I was looking for, but it seemed to bring a smile to everyone else, so I went with it.

There weren’t many constants in my first true decade of adulthood. One of the few was that I only shaved my mustache off once — that one Halloween in 2012 when I went as Lil Wayne. In donning this costume, I hadn’t considered the days that would follow, an early November of feeling like I looked 14 again. I was three years into a 10-year run in New York City, from 2009 to 2019, ages 22 to 32. In that time, my mustache became a distinguishing characteristic, soon followed by a goatee that would eventually, eventually, connect to my mustache and become a full beard.

I also found a barber. I liked him immediately, not just because he was a short distance from where I lived but because he had a vision for me when I had no point of view for myself. When it came to my hair, he saw a future of high and tight, with a natural fade. He used scissors for my hair and beard, clippers for my sideburns and a rounded back, and let me handle my mustache. In my first few visits, he’d ask me about what to do with my hairline. “Don’t touch this!” I said, pointing to the middle of my forehead. I’d look down when I’d say this, and he’d say, “OK, boss.” Soon, it wasn’t even a point of conversation. Just a tacit “we’ll leave your little point, just the way you like” agreement and a shared laugh. I didn’t know why I was keeping it, and perhaps neither did he. Maybe I thought it looked better. Maybe I still wanted to leave something for my mother. Either way, the lack of a pronounced line on my forehead was a decision now, one that I felt good about.

Our relationship was interesting — it was partially the barber relationship I’d fantasized about. I’d text him at all hours, and he responded. If I needed an emergency haircut, he was willing to make time. He wasn’t Black, though, something I wanted to be true. He was always ready with a good story; sometimes I’d talk to him about his family, even if for the first seven years I didn’t know if he was Russian or Puerto Rican. There were times when I thought about ditching him for a Black barber, but I couldn’t bring myself to follow through with it. Even when I moved to Harlem, I continued to trek down to the West Village to see him. Deep down, I loved the idea of turning my brain off, having one thing that didn’t require a worry. Every time I sat in his chair, I relished what I had: a few moments just to sit.

We broke up in January 2020. I was back in New York, my first trip since moving to Los Angeles four months prior. The energy of being back was unlike anything I’d felt. I’d fully done the thing when you make plans with 42 different people — on opposite sides of the city and in different boroughs — without consideration of travel time, traffic or a slow subway.

It had been months since my last cut. I was approaching my awkward hair growth stage, where it stops growing up and keeps growing out, real “Hey Arnold!” hours. So on my final day, I visited my barber. When I walked in and sat in the chair, he was happy to see me, tickled that my hair was so long. It kind of seemed at first as if he thought I had flown in just to see him. I hadn’t, but I had a confession to make: Two weeks before my September wedding, I had stepped out on him, I said, getting an emergency haircut by a rural Virginian named Darrell, who was white. My barber asked me: “Did White Darrell do a good job?” To which I replied that White Darrell did exactly what I asked White Darrell to do, no improv or creative license.

Black curly hair on the top with a little height, flowing into sideburns that are short but not to the skin, a shadowy check and a dark beard that connects to a dark mustache so well it looks like I bought them in a two-for-one deal. That was the look.

When I got out of my barber’s chair, I thanked him for what could actually be our last haircut. It felt good to know what I wanted for myself, a 10-year evolution.

It was graduation day. Or so I thought.

Two months later, we were fully in a global pandemic. Days and weeks increasingly didn’t really mean much. Neither did appearance. My wife and I just made video calls, watched TV, went on walks, ate food and tried to stay alive. It wasn’t until the fall that I realized it’d been eight months since I got a haircut. And my hair was doing something new. It stopped growing out and had gotten taller. My hair was not only long but curly and completely uniform on all sides. This hair unlocked something for me, inside and out.

There’s an energy radiating through the city. Lizzo’s hairstylist Shelby Swain, Hollywood’s Local 706, the nail artists of L.A. and @c0mptonkitty can show you what’s up.

Having long hair became part of my identity. And that expressed itself in the ways in which I started taking care of my new mane. I dipped into my wife’s Rizos Curls (which made me a self-proclaimed Rizos Reina). Soon after, I made my first solo trip to Ulta, which became a bimonthly trip to buy the full Pattern Beauty suite of shampoo, conditioner and leave-in. I used their microfiber towel after washes and liked it so much I’d sometimes wear it out of the house to run errands. Detangling with a brush with eight rows of bristles — hands down, a top-five invention in my lifetime — became a centerpiece of my weekly routine.

On trips home to Atlanta, hair care brought me closer to my mother. I’d plant myself on the carpet, while she sat behind me, picking out the knots in my hair with conditioner, a comb and her fingers. I could tell this meticulous process brought her joy. For decades, my mother wore an Afro that represented her identity and her power as a Black woman — and because it was fly. (One of my favorite Afro-era stories is how a police officer once mistook her for Angela Davis while she was a fugitive, a moment that carried with it both fear and immense pride.) Now I was her curly-haired boy again — and she could tell that I, too, saw what was on top as a point of pride. We’d always had the same face, but our love for our hair and how we presented it to the world connected us on a cellular level. My 20s ushered in a period of looking like my father, but this new moment cemented our bond, as mother and son, and as two proud Black people in America.

By the start of 2022, I had a true hair care routine, a nighttime skin care regimen and oil to keep my beard sharp and healthy. I’d never considered that a bathroom vanity could evolve into a sanctuary. I slowed down, taking time to care for myself, which in turn gave me a stronger sense of self-love. Sometimes I’d stare at myself and think, “Who the hell am I?” I wasn’t upset, I just couldn’t believe my life had taken this turn. But I loved how much I cared. And how much I needed a new headshot.

My hair was more than a fire accessory. It complemented me in a way I had not yet encountered. As if I’d tapped into something about myself that I previously didn’t know.

— Rembert Browne

When we started leaving our home and seeing our loved ones, double takes became a frequent reaction. Be it friends and family from home or homies from college or New York, no one had seen me like this. The consensus was that my new look felt right, as if it matched my energy.

My hair was important to me now. My mom and my wife liked it, so I loved it. Clothes that never worked for short hair were now hitting with my newfound growth. And yet, my hair was more than a fire accessory. It complemented me in a way I had not yet encountered. As if I‘d tapped into something about myself that I previously didn’t know.

I’d vacillate between bold and beautiful. Sometimes the long hair would make me feel stronger, other times soft and tender.

Not only did I have a ’fro, but I knew my hair type better than my blood type. And with those curls, poofing up but also covering my ears and forehead, a new reality emerged: I had a new hairline.

My widow’s peak was still there, in plain sight if I pulled my hair back, but when my hair would dry and grow to its full form, it would be hidden under a line of curls that extended out and hung slightly down. And the thing about that line of curls — it was straight.

My face, finally framed the way Black Jesus intended. And, as the Book said, it was good.

Rembert Browne is a writer from Atlanta. He lives in Los Angeles.

More stories from Image