This story is part of Image Issue 14, “Elevation,” where we examine beauty as a state of being, a process of realization. Read the whole issue here.

With my work in general, I’m always trying to display process. Getting ready, in my version of beauty, is very minimal. Gotta wash the face. Gotta be moisturized — gotta be moisturized.

Most of my work is ritualistic or meditative. Especially in this phase of life, which is a very reflective stage of just being so aware of all the things but also trying to stay present and not internalize all the things. I try to be intentional. I just finished the braids that are in my hair, which took me almost a month to do. Anything that has some sort of repetition, I think, puts you in a meditative, trance-like state where you can zone out and be with your thoughts.

Anytime I’m doing anything with my hair, I’m transported to my childhood. Because I grew up in a hair salon — my dad had a hair salon called Tweet’s. The gel that I use on my hair is the same exact gel that I used when I was a girl, so whenever I open that jar, it’s like literal time travel. Scent can allow you to time travel.

The tightness that comes with a face mask — it’s like contracting and releasing, in a way. It kind of is a metaphor, how life contracts and then releases.

It’s so beautiful to see these brands flourish — these are people that I’ve seen come up from their first Instagram posts: Hanahana Beauty, Golde and Baby Tress. Now you can go to Target and just buy things. And that’s pretty tight.

More stories from Elevation

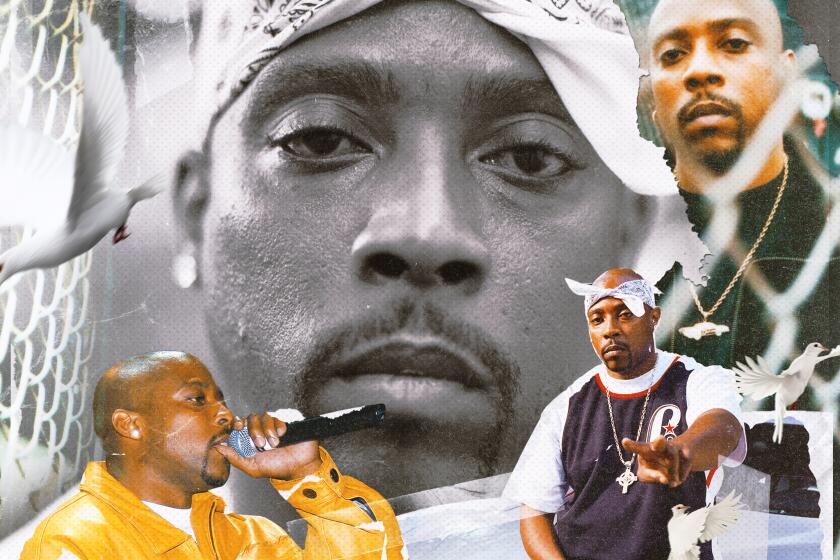

Jason Parham revisits the Smokey Robinson of hip-hop, Nate Dogg

Rembert Browne comes of age without a hairline

Devan Díaz takes on tweezing as self-care in our warped times

Dave Schilling investigates why the mullet is the haircut that refuses to die

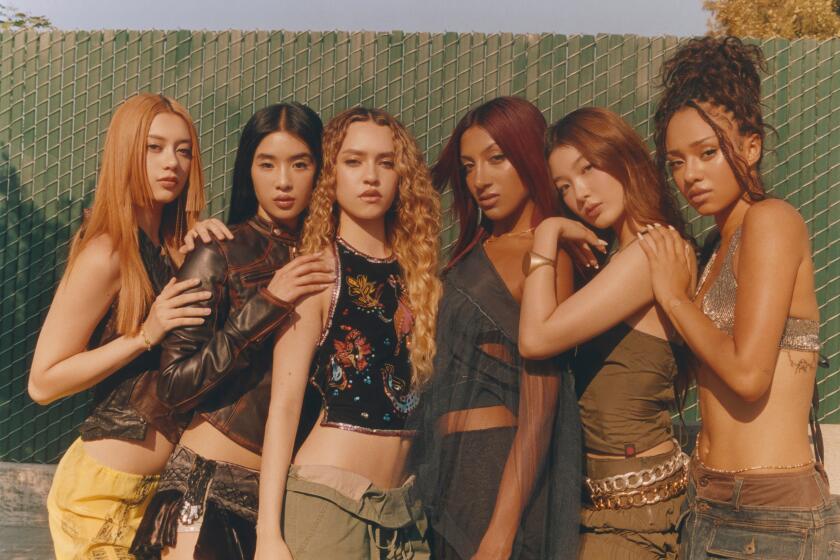

The state of L.A. beauty in one zine

I think so many things are beautiful — like everything. Honestly, I’m just the person who will find it. I think that’s a reflection of my life. Because I’ve had a really interesting life, with a lot of what is seen as tragedy, like losing my mom, losing my dad, losing a few siblings as well. Since I was a kid, I’ve been looking for a way to make the situation a little bit more beautiful, a little bit lighter. But when I hear the word “beauty,” I literally do not think of appearance. The word is so beyond that to me.

I shot this in my space, in my bathroom, in my room. So I guess it’s a direct reflection of the warmth of the space I occupy. But also, some of the images, like the one in the mirror with my mom and the photo, I wanted to intentionally share that I have photos, little corners of my mom. My mother passed away when I was 1½. I pay reverence to her. And she was so beautiful to me. I think that that’s what I was really trying to convey — my mother is so beautiful. That this is Black beauty right here.

Rikkí Wright is a photographer-filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist moving through the mediums of printmaking, documentary and ceramics. Wright is interested in and concerned with notions of community and kinship, especially among people of color, and looks at the way this connectedness can mold or expand ideas of self and ideas of existing. Working with the personal and historical archive, Wright is granted access: a space to remember, imagine or reimagine histories. Wright’s work also investigates the politics of beauty and desire through self-portrait photography and various other mediums.

More stories from Image