When Rite Aid Corp. decided to build a giant warehouse to serve its Southern California stores in 1999, it chose an isolated stretch of the Mojave Desert where the air vibrates with heat in the summer.

The land was cheap. The freeway was nearby. But during summers, the workers are boiling inside the mostly non-air-conditioned warehouse.

They say their leg muscles cramp and their hearts race. They sweat through their clothes. Made sluggish by the heat, they struggle to pull products at the pace the company sets, incurring demerits that threaten their jobs. In interviews with the Los Angeles Times, Rite Aid workers said at least three employees fell ill with heat exhaustion in June, when an unusually severe heat wave descended on Southern California. Two became so dehydrated that they needed IV bags of saline solution to replenish lost fluids.

Workers say supervisors responded to their complaints with promises to install more fans in the warehouse, which at nearly 1 million square feet is large enough to fit three Walt Disney Concert Halls. But even when they’ve followed through, it’s had little effect as Southland temperatures rise.

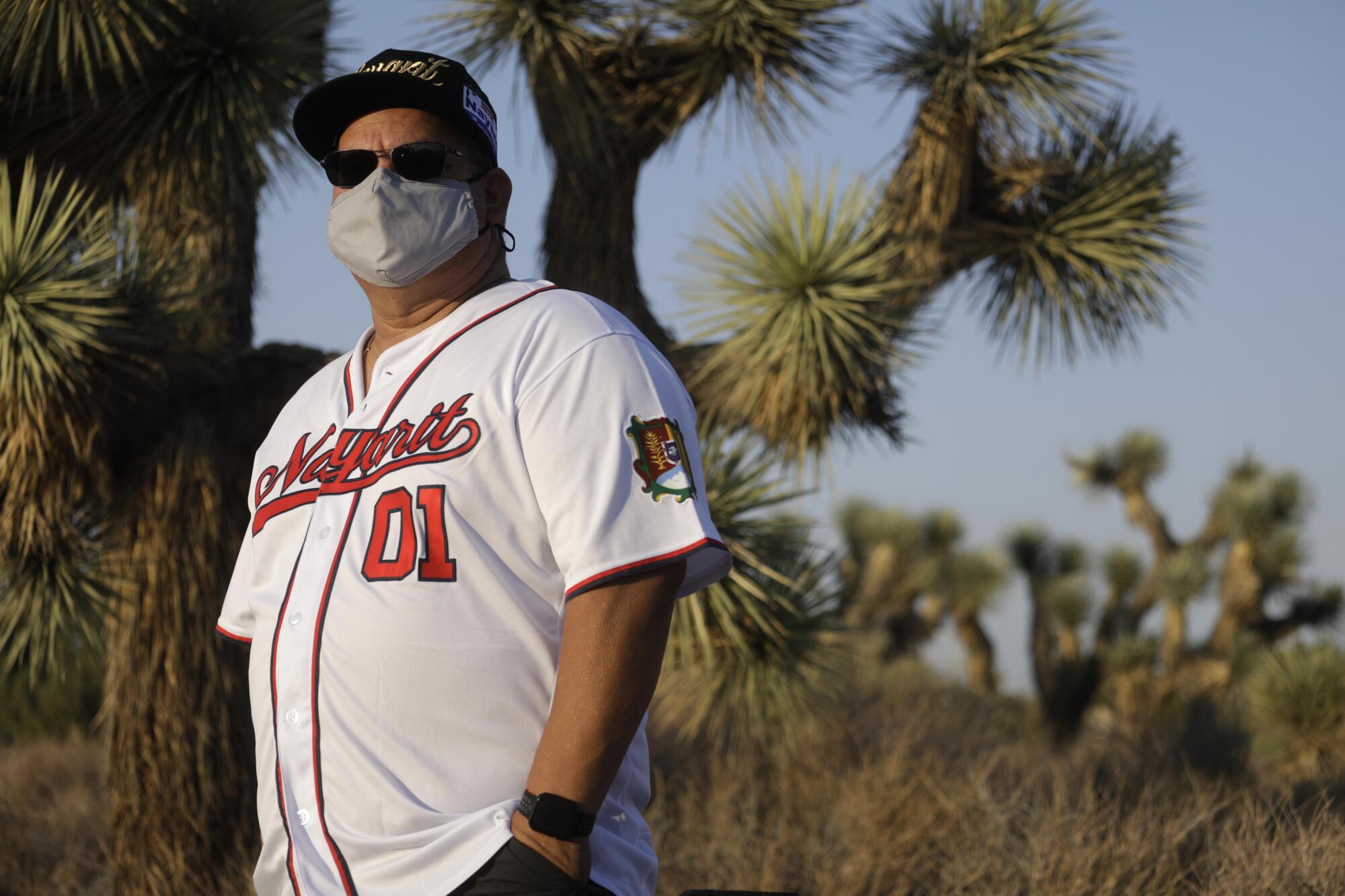

Marleni Ortiz is all too familiar with the rapid heart rate and headaches that signal the onset of heat exhaustion. The 27-year-old said she was on the verge of collapsing in the warehouse twice this summer.

At home, Ortiz sometimes sits on her bed before work and contemplates her life. “Do I really need to go?” she asks herself.

“But I have two kids. I need the income. It’s really depressing because it’s so hot in there,” she said.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

The conditions inside Rite Aid’s Lancaster facility underscore the dangers facing warehouse workers across California, where major retailers are expanding aggressively against a backdrop of increasing temperatures.

Fueled by customers’ growing addiction to one-day delivery and a pandemic-driven surge in online shopping, demand for warehouses has skyrocketed. As land near major ports and cities becomes scarcer and pricier, developers are heading deeper into the Inland Empire and the Central Valley, where temperatures are rising faster than in coastal communities. Low-wage workers, most of them Black and Latino, are facing increased risks as they follow the job boom to some of the hottest parts of California, into warehouses that industry experts say are mostly not air-conditioned.

While the White House has recently taken up the issue, state regulations limiting indoor temperatures have been long delayed. The state doesn’t require indoor air conditioning.

The Times interviewed more than two dozen warehouse workers, logistics industry experts and advocates for workers’ rights, and reviewed documentation of a worker’s heat complaint obtained through a public records request. They described how increasing temperatures are jeopardizing warehouse workers’ health and safety at a time when demand for workers willing to take these jobs is growing.

Rite Aid workers thought they’d made progress in 2011 when, after years of negotiations, a majority of the warehouse’s 500 employees approved a union contract with new rules to prevent heat illness. But a decade later, workers at the huge facility say the protective measures they fought for are insufficient in the face of record heat.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

In 2016, the state enacted a law requiring California’s Division of Occupational Safety and Health, better known as Cal/OSHA, to set limits on indoor heat. Those limits are still under review. Even if the state eventually enacts an indoor heat standard, it’s not clear that Cal/OSHA is capable of enforcing it. The agency’s ranks are thin; it has been underfunded for years. An agency spokesman said Rite Aid workers have filed three complaints about indoor heat since 2015. None resulted in a penalty.

Rite Aid spokesman Bradley Ducey said the company has been working with its employees and their union to address increased temperatures. He said the company has installed more fans, opened doors in the evening to let in cooler air and allowed workers to take rest breaks and access “cooling spots.” He said Rite Aid shifts its employees’ work hours during the hot summer months to cooler parts of the day — though employees said this effort has been impeded by demands for mandatory overtime.

“We constantly review and evolve our policies, and seek feedback on indoor temperature management in partnership with Cal OSHA and union representatives,” Ducey wrote in an email.

We have this giant frickin’ refrigerated room to keep the chocolate from melting. While people are practically ... dropping off.

— Debbie Fontaine

Eight workers said there is only one work area in the warehouse that’s air-conditioned — the chocolate room, where Rite Aid employees inventory and sort bags of Hershey’s Kisses and Snickers bars before they’re sent to drugstores across the Southland.

Debbie Fontaine, who has worked in the warehouse for 21 years, said it’s common for supervisors to walk employees to the chocolate room when they begin to feel faint from the heat.

“We have this giant frickin’ refrigerated room to keep the chocolate from melting. While people are practically ... dropping off,” Fontaine said.

The rise of the logistics empire

Stirred by reports of deaths in the Pacific Northwest after a record-breaking heat wave this summer, when temperatures reached a high of 116 degrees in Portland, workers’ advocates and politicians have seized on the plight of millions of farmworkers, construction workers and other outdoor laborers. And for good reason — climate change has already warmed the world by 2 degrees Fahrenheit and is making heat waves more frequent and more intense, exposing outdoor workers to extreme heat with deadly consequences.

Yet the conditions faced by indoor workers in garment factories, steam-filled restaurant kitchens and warehouses have received far less attention. A new study from researchers at UCLA and Stanford suggests that indoor workers in California, like outdoor workers, are more likely to be injured on the job when temperatures climb into the 90s, and that work injuries linked to extreme heat are vastly undercounted in official records.

But climate change hasn’t stopped the warehousing and logistics industry from building in inhospitably hot climates.

AB 701, headed to a Senate vote this week, is the first legislation in the U.S. that would regulate warehouse performance metrics.

According to data provided by the research firm CoStar Group, since 2010 more than 400 new warehouses, each over 100,000 square feet, have been built in the Inland Empire, where triple-digit summertime temperatures are normal. Today, about 10% of all warehouses in the United States are located in this part of Southern California, according to Paul Granillo, president of the Inland Empire Economic Partnership, an industry-affiliated group.

New warehouses continue to spring up east of the old ones in high-heat cities such as Beaumont and Banning in Riverside County, and Victorville and Hesperia along the southern edge of the Mojave Desert.

“This trend was already growing,” Granillo said, “but the pandemic has just supercharged it.”

The Coachella Valley, which matched its all-time high of 123 degrees in June, could be next, he added.

Exactly how many warehouse workers are getting sick and dying from extreme heat is impossible to say. Cal/OSHA does not track this information, and employees are often reluctant to endanger their jobs by reporting injuries or illnesses.

Some warehouse employees have banded together to demand better conditions, winning concessions at a few work sites. They are the exception. Industry experts said that most warehouses continue to rely on large fans and industrial exhaust systems to circulate air. Only managers’ offices and employee break rooms are typically air-conditioned.

Fans can help employees stay cool, especially in humid environments that make it difficult for sweat to evaporate. But researchers have found that on blistering days, fans can make conditions worse by blowing hot air on workers’ already hot bodies.

The flaws of this approach were clear to Mariana Estrada, a UCLA graduate student who spent the summer of 2017 as a “picker” in one Amazon warehouse, known as ONT6, in Moreno Valley, a city in Riverside County. Estrada said certain parts of the warehouse — the hallways, human resources office and nurse’s office, for example — were air-conditioned. The company maintains that the entire warehouse was air-conditioned, but Estrada said it was extremely hot where she worked. There were fans at the end of every other aisle. If she was told to fill orders near the fans, it felt like she’d won the lottery, she said. But if not, the heat was brutal and the work physically demanding.

“They were always trying to get you to move faster,” Estrada said. Supervisors sometimes chanted, “One step per second,” to get workers to pick up their feet. “In terms of heat vulnerability, that just adds another level to the dangers workers experience.”

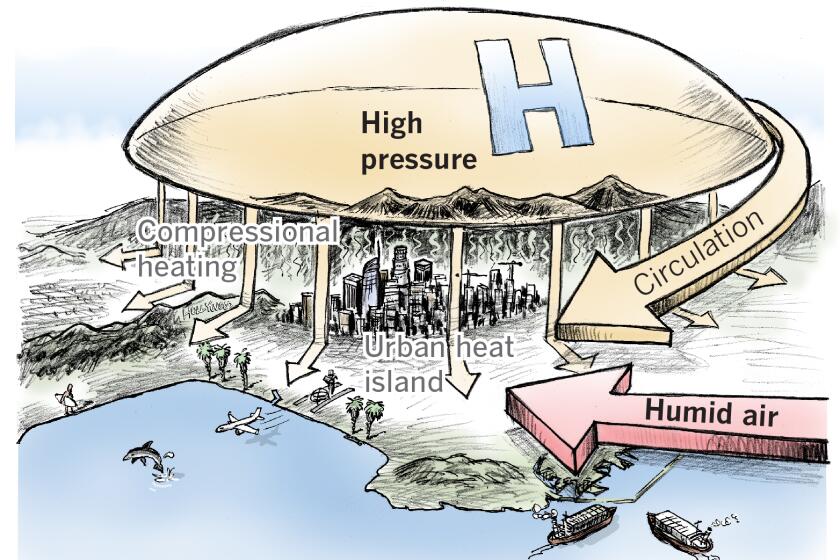

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

Amazon spokesperson Barbara Agrait said that although it’s “not industry standard,” the company is proud that all of its California fulfillment centers are air-conditioned. But in addition to these centers, where employees pick, pack and ship items, Amazon operates several other types of warehouses and facilities, some as large as 600,000 square feet, where inventory is sorted and grouped for shipment. When asked, Agrait did not say whether these are also cooled.

The effectiveness of the warehouses’ cooling systems is less clear. Several current and former Amazon employees interviewed for this story said the fulfillment centers are cooler than the company’s other warehouses, but that parts of the buildings are still very hot. They said employees who load and unload trailers frequently complain about being exposed to extreme temperatures during the summer months.

“The quality of AC seems to depend on which facility you are in and where you’re located in the warehouse,” said Ellen Reese, a sociology professor at UC Riverside who studies labor conditions at Amazon in the Inland Empire and whose research team has collected interviews with 82 current and former Amazon warehouse employees. While some warehouse workers consider AC one of the perks of working for Amazon, Reese said, others say they are too hot when temperatures climb.

Asked whether its warehouses are air-conditioned, Costco declined to comment. A Walmart spokesperson said the company has made “significant and ongoing improvements to airflow” through the use of fans and other measures, but declined to say whether its warehouses have air conditioning. Similarly, a spokesperson for Target declined to answer questions about whether the company’s warehouses are entirely air-conditioned. She said the buildings have air-conditioning units and use a variety of other methods to control indoor temperatures.

A Home Depot spokesperson said the company has different types of temperature-controlled warehouses, depending on the area of the state, the type of work being performed and how open the facility is to the outdoors. She did not answer questions about whether any of them are air-conditioned.

The extreme temperatures warehouse workers face are avoidable, said Tim Shadix, legal director of the Warehouse Worker Resource Center.

“There are food or pharmaceutical warehouses — they have no problem keeping those climate-controlled,” Shadix said. “It’s a profit thing, where they’re not willing to do that to protect humans.”

Inside the warehouse

When Jesus Ramos finishes work during the summer, he doesn’t race home. After hours inside the warehouse, he’s exhausted, his vision is blurry and his clothes are soaked with sweat. He fears he’s in no condition to drive.

“I stay in the parking lot a little while, turn on my car with the AC on to try to cool my body down,” he said. “That’s every day in the summer.”

Temperatures inside the Rite Aid warehouse can climb to 90 degrees or higher and simmer there for hours, according to workers and a week’s worth of the drugstore company’s 2020 temperature records. Photos of temperature readings workers shared with The Times show that on a scorching day last July, it was already 88 degrees inside the warehouse by 5:30 a.m.

Under the union contract, supervisors are required to give workers a five-minute break when temperatures reach 90. They get a 10-minute break when it hits 100 degrees. The union stewards carry their own digital heat monitors to keep managers honest, but they acknowledge the breaks don’t offer much relief.

By contrast, military personnel stationed at nearby Edwards Air Force Base are protected by heat regulations that require 40 minutes of rest for every 20 minutes of work when they are performing moderate labor in temperatures over 90 degrees.

Tap water is available for drinking, but some Rite Aid workers interviewed for this story said that what comes out of the warehouse’s faucets is “gray,” “really dirty” and “doesn’t taste like water.” One employee said she brings in six bottles of water every day. A Rite Aid spokesman said the company filters its water.

Some workers said they check the weather forecast in the morning and, on occasion, decide to stay home to avoid the heat, forfeiting a day’s pay.

When workers complain to supervisors, Ramos said, “their reaction is always, ‘We can’t do anything about it — it’s upper management.’ That’s as far as it goes.”

What are heat-related illnesses and how are they treated? Are they preventable or inevitable? We talked to health experts for the answers.

Ortiz, the employee who suffered two bouts of heat exhaustion, said she returned to the warehouse after her second episode with a note from her doctor recommending that she be allowed to work in an air-conditioned space for the rest of the summer. She was overheating, her joints ached and her psoriasis was flaring. She said Rite Aid denied her request.

Some of the conditions workers described were difficult to independently verify. Rite Aid refused to allow a reporter and photographer inside its Lancaster warehouse, and a company spokesman declined to answer questions about Ortiz’s experience or that of other employees.

Occupational health experts say most heat-related deaths and injuries occur among new hires who aren’t used to working in hot weather. But in just the last two years, at least four longtime Rite Aid warehouse employees have fainted or come close to passing out from heat exhaustion, according to employees.

In August of 2020, Martha Ramos, who’d been at Rite Aid for nearly two decades, told the co-worker standing next to her that she wasn’t feeling well and then collapsed on the warehouse floor. By the time Ramos’ assistant manager found her, Ramos couldn’t do much more than nod her head yes or no, according to records of the supervisor’s interview with Cal/OSHA. She took Ramos to an air-conditioned break room and held her shaking body while they waited for an ambulance.

Ramos declined to be interviewed for this story, but the documents obtained by The Times through a public records request show that when a warehouse manager reported her fall, he blamed her.

Safety manager Lee Gay wrote in his report that the incident was caused by Ramos’ “failure to follow training” and her “failure to hydrate properly.” Beneath the question, “Why was the unsafe act committed?” Gay put Xs next to “lack of knowledge or skills” and “improper job attitude.” Nowhere on the form did he report that, according to Rite Aid’s own records, it was about 87 degrees inside the warehouse when Ramos passed out at 10:15 a.m. — three degrees below the threshold for rest breaks.

Gay did not respond to requests for comment.

Ramos told a Cal/OSHA investigator that she had consumed three 32-ounce bottles of water that morning. “No matter how much water I drank, it would not cool me down,” she said, according to the investigator’s notes.

Cal/OSHA closed the investigation after finding that conditions inside the warehouse didn’t violate state standards.

Regulating heat

The fight to set a limit on indoor heat in California workplaces is nearly 15 years old and still unfinished.

In 2007, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the first bill to pass the state Legislature that would have created an enforceable standard — a temperature level above which the state considered it unsafe to work. He maintained that California’s workplace safety board was already looking into the question.

Schwarzenegger’s position aligned with many of California’s powerful business interests. Nine more years would pass before the near-death of a warehouse worker in the Inland Empire prompted lawmakers to try again in 2016.

This time they were successful. Gov. Jerry Brown signed the bill into law, requiring Cal/OSHA to begin work on regulations.

Utilities have funds available to install air conditioning in low-income households, but for one California family, help did not come soon enough.

The agency’s records show that the California Chamber of Commerce argued for a rule that would only apply to non-air-conditioned workplaces where the temperature was 95 degrees or higher. Advocates for workers’ rights insisted on a floor of no more than 80 degrees. The agency compromised, issuing a draft rule in 2019 that set a limit of 87 degrees, or lower than 82 degrees if employees were wearing protective clothing or working near heat-generating equipment. Those limits still haven’t been finalized.

For now, the agency’s inspectors have few tools at their disposal. They can cite an employer for not fixing a broken air conditioner or for having an unsafe work environment. But without clear rules stating the temperature at which heat is hazardous, most businesses face no threat of enforcement action. Cal/OSHA can’t even say how many complaints about indoor heat it has received. It doesn’t count them.

I can imagine some companies really hedging their bets and trying to wait out enough automation so that they reduce human exposure to the heat.

— Beth Gutelius

In September, the Biden administration announced that it would draft the nation’s first rules on workplace heat for outdoor and indoor settings and would prioritize workplace inspections on days when the heat index exceeds 80 degrees.

As the state and the federal government consider whether and how to crack down on companies that are exposing workers to extreme heat, warehouse operators and logistics companies are increasingly looking to robots. Across the Inland Empire and the Central Valley, machines are picking, packing, lifting and unloading — taking on some of their human counterparts’ most tedious and labor-intensive jobs.

Companies say this shift helps them survive during labor shortages. But it has the added benefit of introducing robots that don’t need bathroom breaks, can’t join unions and can tolerate much colder and hotter temperatures than humans.

“I can imagine some companies really hedging their bets and trying to wait out enough automation so that they reduce human exposure to the heat,” said Beth Gutelius, research director of the Center for Urban Economic Development at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who studies workplace automation. “It’s a pretty dark possibility.”

Robots are not expected to displace large numbers of warehouse workers anytime soon, according to a study Gutelius wrote in 2019. As e-commerce companies expand in California, signs advertising open positions are everywhere.

Meanwhile, for the second time in two years, Cal/OSHA inspectors are investigating a complaint of unsafe temperatures in the Rite Aid warehouse.

This time, the union local’s president said, the complaint concerns an employee who has suffered heat exhaustion twice in the last two years. She filed a complaint this summer after becoming so weak and disoriented that her doctor urged her to find a new job.

To protect herself at work, she bought a small portable fan that she could wear around her neck. Other Rite Aid workers did the same. Without it, she said, “somebody is going to be waking me up with smelling salts.” She ordered it from Amazon.