As heat waves intensify, access to air conditioning can mean life or death

CATHEDRAL CITY, Calif. — Cory Hammond pleaded with his parents to come stay with him in mid-August of 2020, when they were living without air conditioning in this desert community just east of Palm Springs.

Forecasters had issued an excessive-heat warning — of temperatures up to 118 degrees.

“You have all sorts of thoughts that run through your mind,” Hammond said, recalling his conversations with his parents, Sandra and Richard Hammond. “You know the heat is coming. You know it’s miserable.”

That week, the elderly couple used a swamp cooler and fans to try to cool their home. Their central air-conditioning unit was broken, and they couldn’t afford to replace it.

But there was hope of relief through a utility program that offered low-income customers free energy-saving improvements and appliances, including air conditioners.

The salvation they sought, however, did not come in time. Fans and the swamp cooler — a device that blows air over evaporating water — also proved to be inadequate for the heat. And after a week of triple-digit temperatures in Cathedral City, 78-year-old Sandra Hammond died from heatstroke.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

As heat waves intensify, access to air conditioning can mean life or death for people in California and other states. Federal data show that poor families have a far lower rate of air-conditioning units in their homes than the average family, and even when they have AC, they are reluctant to use it or get equipment fixed, because of the cost.

That was the situation for the Hammonds, who lived on a fixed income. Even when their central air unit worked, they rarely used it.

“They would only run it on the super hot days just to help kind of take off some of the heat,” Hammond said. “So while you may be able to find some grace to repair [it], you’re still looking at a $400 or $500 electric bill.”

Two potential lifelines exist for such families. One is the federal Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which is administered by state agencies. Congress has slashed its funding the last decade, from $5.1 billion in 2009 to $3.7 billion in 2021, and experts say much of the remaining funding is focused on helping people winterize their homes, not cool them in the hotter months.

What are heat-related illnesses and how are they treated? Are they preventable or inevitable? We talked to health experts for the answers.

In California, utility companies offer the Energy Savings Assistance (ESA) program, which is funded by ratepayers. The program seeks to improve energy efficiency and ventilation for low-income households. The Hammonds had enrolled in that program.

Last year, the COVID-19 pandemic caused regulators to temporarily suspend the program in March, and the Hammonds were forced to wait during one of the hottest summers on record.

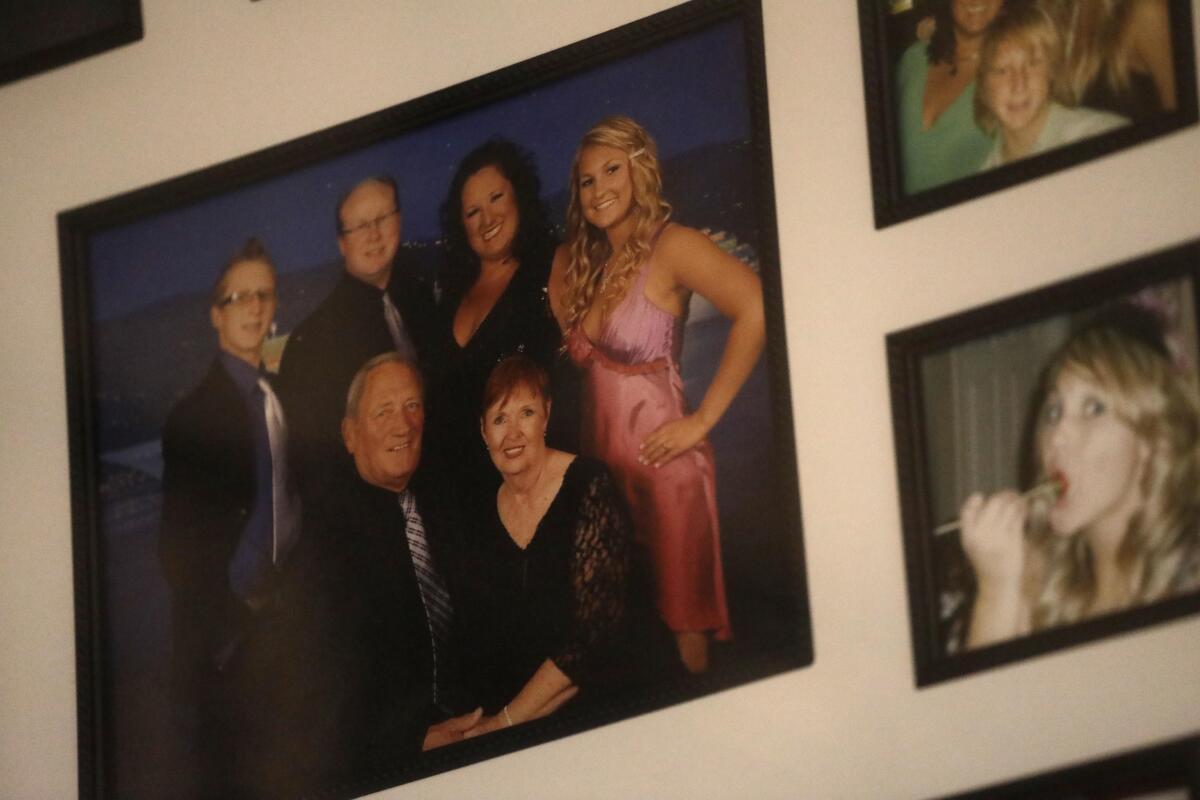

Extreme heat is part of life here, and Sandra Hammond learned to adapt to it. She was born in Portland, Ore., and later moved to Seattle, one of the wettest cities in the country. That was where she gave birth to her only child, Cory.

In the early 1970s, he and his mother moved to the Coachella Valley, to be close to family. It was there she met and married Richard Hammond, a roofer who had spent about 50 years working outdoors.

“So he was used to the heat,” Cory Hammond said.

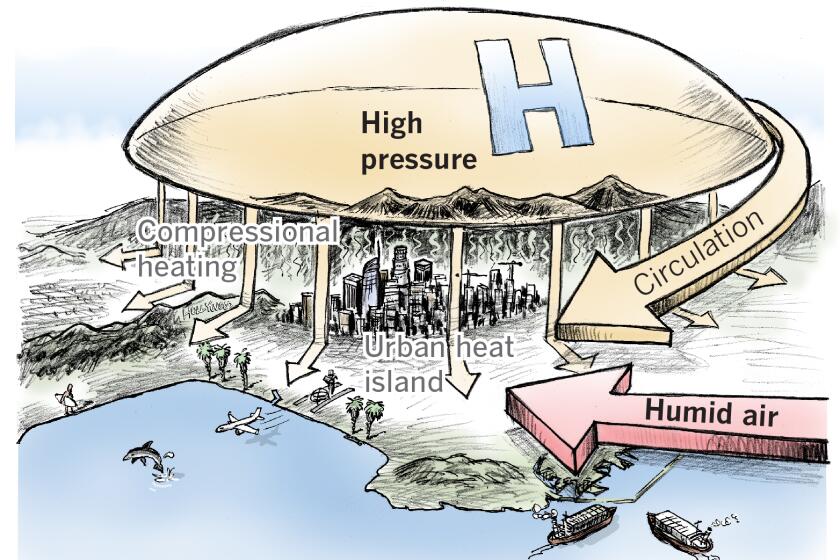

California’s worst heat waves arrive in a one-two punch — high temperatures combined with humid air from Baja.

The mother and son gradually adjusted to the desert climate. The summers were “atrocious,” Hammond, 52, recalled, but in other months, he grew to love the desert’s beauty, the “clear skies, clean air and nice mountains.”

Over the years, Hammond and his mother began to take note of changes in the region’s climate. The normal summer heat waves were stretching into the fall and winter.

“It used to be that in August and September you’d start seeing some cooling trends,” Hammond said.

Temperatures have been climbing steadily for the last few years in the Coachella Valley, toppling records that were set a half-century ago, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Weather Service.

Ivory Small, a meteorologist with the San Diego National Weather Service, said that within the last 20 years, seven of the 10 hottest Julys on record have occurred in the Coachella Valley. A similar warming trend is happening in other nearby areas, and that pattern, he said, is “going to continue for a while.”

With heat waves becoming hotter, longer and more frequent, Hammond was grateful upon hearing that his mother’s friend had enrolled his parents that July in the state ESA program through Southern California Edison.

He hoped the program would provide his parents with air conditioning that summer, but what he didn’t know was that Edison, from March until June that year, had suspended “face-to-face interactions” between its contractors and customers due to the governor’s stay-at-home pandemic order. Among those caught in this backlog were his parents.

Read all of our coverage about how California is neglecting the climate threat posed by extreme heat.

In 2018, the utility saw more than 86,000 customers enroll in the program. The following year it jumped to more than 95,000. Last year, due to the pandemic, about 60,000 customers enrolled.

The utility expects the enrollment numbers to climb again after the pandemic is over, and it will see its budget grow from $65 million this year to more than $80 million. Overall, it proposed to spend more than $390 million on the program for the next five years.

On Aug. 18, 2020, Sandra Hammond suffered heatstroke. Richard Hammond, who was at home with her, had been asleep, thinking his wife was also napping.

The friend, the same one who helped enroll the couple in the program, stopped by to check on them and noticed Sandra Hammond was struggling to breathe. She dialed 911, and paramedics transported Hammond to Desert Regional Medical Center in Palm Springs, according to Cory Hammond and a Riverside County coroner’s autopsy report.

Hammond said his mother was revived at least twice, once on the way to the hospital and again in the emergency room.

The autopsy report said his mother’s body temperature was 106 degrees when she arrived at the hospital.

Hammond said he was unaware of what had happened to his mother until he got a call from the hospital. He and his father couldn’t visit because of COVID-19 restrictions.

The next day, doctors told him his mother couldn’t wake from a coma and needed to consider a “do not resuscitate” order.

“So at that stage, it’s a family wrestling decision,” he said. “Do you give them a fighting chance or do you not?”

Hammond said he gave his mother a chance. The medical staff took care of her until they couldn’t do any more. The hospital allowed him and his family to see her one last time. He said his mother held on long enough for everyone to say farewell.

“I’m just very thankful I was able to see her,” he said.

After his mother’s funeral, Hammond’s focus turned to his father, who was still at the house as the heat waves continued.

Hammond said it wasn’t until January that they received an update on his parents’ enrollment in the ESA program.

Diane Castro, a spokeswoman with Southern California Edison, said that in order to protect the privacy of its customers the company could not provide information about program enrollment or account history.

Hammond said his parents qualified for an energy-saving refrigerator, evaporative cooler and central air conditioner replacement.

In February, Hammond said, an independent contractor with Southern California Edison showed up to assess his father’s property.

Then came more setbacks.

Hammond said the contractor didn’t do rooftop installations of evaporative coolers. When Hammond suggested it be placed on the bedroom window, they found they couldn’t because there was only one window in the room and it created a fire hazard.

State and municipal codes require that a bedroom must have at least two escape routes in case of an emergency.

Then there was the central air unit outside. Hammond said it couldn’t be installed because the contractor told him it required 3-foot clearance from the neighbor’s fence line.

In the end, he said his father got a new fridge, and later, a small AC window unit from a private company, not affiliated with the ESA program. Hammond said he’s still trying to find a way to replace the central air unit through the program.

In the meantime, he’s tried to persuade his dad to live with him, but hasn’t succeeded yet.

“I’m trying to prevent losing my father the same way.”