Sanctity and sex in installations devoted to chapels and cruising at Venice Architecture Biennale

The beauty of the Venice Architecture Biennale is that over the course of an afternoon, you can check out a spiraling, ethereal installation by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa’s Tokyo firm SANAA, then trot over to another building and see diagrams of an imaginary city conjured by experimental Dutch collective Crimson Architectural Historians.

The juxtapositions can get even weirder.

On Friday evening at 6 p.m. local time, the Vatican unveiled a series of 10 architect-designed chapels in a lush garden on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore — its first contribution ever to the biennial architectural show. Exactly one hour later, and one island away on La Giudecca, a group of international architects and designers opened the doors on an unsanctioned exhibition devoted to cruising — as in, for sex.

Needless to say, there is no Friday night in Venice like one spent traipsing around exhibitions devoted to quiet prayer and the pursuit of sex.

Herewith, my full report:

Thou shalt stand in line

The Holy See knows how to draw a crowd!

Twenty minutes before the show a crush of well-heeled partygoers is already trying to hold off the dampening effects of the evening heat by fanning themselves with their embossed Vatican invitations.

The crowd grows so dense — easily in the hundreds — that when we are finally admitted into the garden, the mass of humanity moves along the path like a slow procession of super stylish penitents. This inspires the woman next to me to describe her pilgrimage of the Camino de Santiago in Spain. (I would tell you more about her experiences, but my Italian is rusty.)

Cardinal on the loose

I begin the tour at Brazilian architect Carla Juaçaba’s flashy-minimalist chapel, which consists of a simple, skeletal frame that offers a single, polished steel plank as bench.

Throngs of passersby snap pictures. A few sit on the unusual pew (which, for the record, is more uncomfortable than a regular wood pew).

The attention is all on Juaçaba’s chapel — until Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, president of the Pope’s culture council, materializes with members of the press in tow. At that moment, all discussion of architecture goes out the window as everyone whips out their cellphones to grab a picture.

Ravasi is the culture-loving cardinal who helped make the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Heavenly Bodies” exhibition possible. He also helped push for the Vatican’s participation in the Biennale, which was curated by Italian architectural historian Francesco Dal Co.

Throughout the evening, Ravasi is treated like a rock star. He stops to view (and regally pose at) each chapel, unleashing a rush for cameras all along the route. This means that some chapels briefly turn into paparazzi scrums.

But they are holy paparazzi scrums. Because nothing will leave you feeling closer to God than fighting off an Italian TV crew for the best shot.

Imaginative pavilions

When the Vatican’s architectural project was announced in March, Ravasi said that visiting the sequence of 10 chapels would serve as “a sort of pilgrimage.”

“It is a path for all who wish to rediscover beauty, silence, the interior and transcendent voice,” he said in a statement at the time, “the human fraternity of being together in the assembly of people, and the loneliness of the woodland where one can experience the rustle of nature which is like a cosmic temple.”

And while some of the chapels feel more cosmic than others — all offer singular experiences.

A concrete barrel-like vault designed by Chilean architect Smiljan Radic looks brutal, but its warm acoustics (attributed to an interior lined with paper-mache) provide a comforting sense of shelter once you stand within its walls.

An open-air chapel by Spanish architects Eva Prats and Ricardo Flores has strategic cut-outs to admit heavenly sunlight and glimpses of trees, while a geometric structure by Pritzker Prize-winning British architect Norman Foster makes dramatic use of the outdoors. Its rippling, slatted wood walls frame views of the water and the island of Lido in the distance.

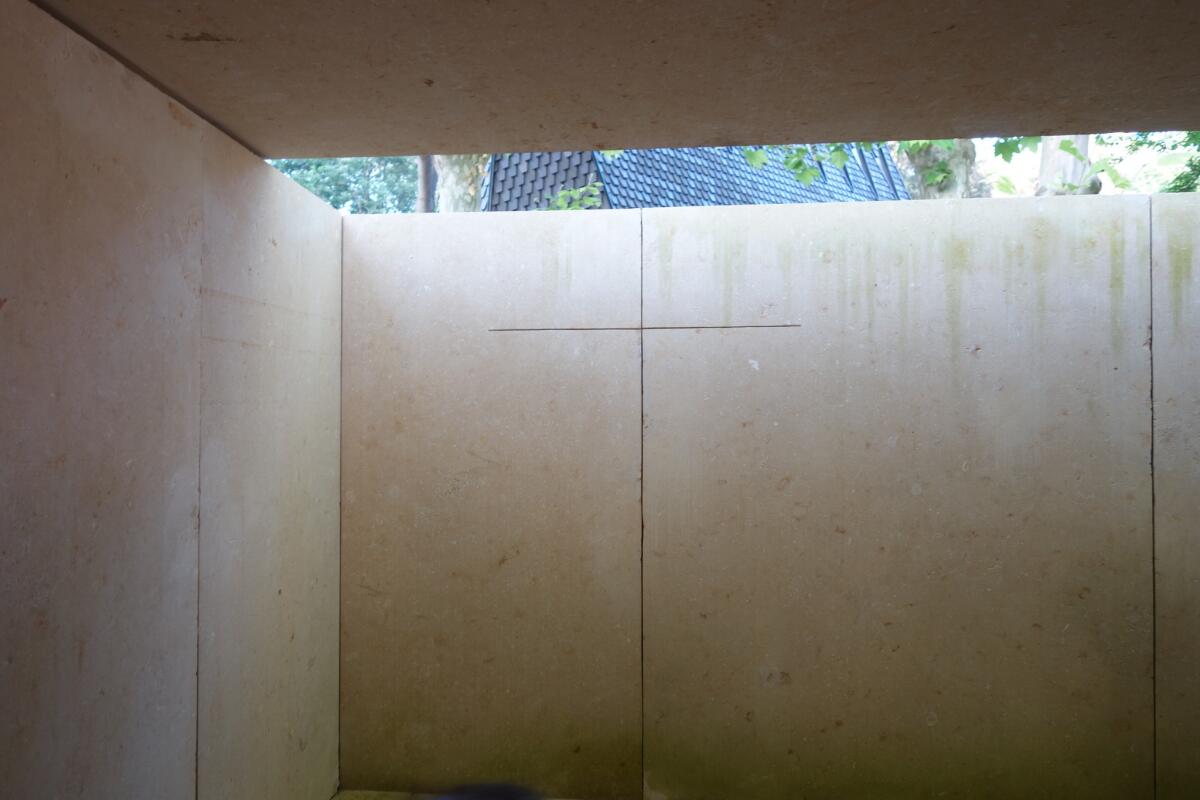

But perhaps most remarkable is the structure by Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura, who erected a simple travertine temple that descends into the ground. Enter, and you’ll find yourself before an altar and a simply rendered cross, one that elegantly employs the seam between two sections of travertine as its spine.

Even with the jamming crowds, it evokes a quiet respect.

Ready to cruise

As the society ladies all around us begin to realize that at this architectural party there will be only good spiritual vibes and no Campari spritz, we figure it might be a good idea to beat them to the water taxi before the lines get too long.

Our next stop: the unofficial Cruising Pavilion, staged at the nonprofit Spazio Punch gallery on Giudecca island.

Organized by a gaggle of four European curators, the show examines the ways in which LGBTQ culture has appropriated semi-public locales such as bars, baths and clubs to create safe spaces for the pursuit of sex. Featured in the show are figures such as artist Monica Bonvicini, research-based architect Andrés Jaque and the Office for Political Innovation, even the high-profile team of Diller Scofidio + Renfro (who present video of its Blur Building, a foggy pavilion that in this context evokes a bathhouse or steam room).

If the Vatican show had taken us into the light, the Cruising Pavilion takes us right into the dark — a warehouse gallery transformed into an environment reminiscent of a throbbing, multilevel queer club.

The best part: Anyone who walks in the door can pick up a free condom.

The architecture of sex

It might be easy to consider the Cruising Pavilion a bit of architectural spit-balling — a subject intended to poke fun at the stuffier projects in the sanctioned exhibits at the Biennale across the canal. But that is not the case.

The show indeed approaches its subject with humor. One theater-like installation mixes clips of an old Marguerite Duras film about lonely Parisians chatting on abandoned World War II-era phone lines with snippets of gay porn. (The latter, a flick poetically titled “Dawson’s 20-Load Weekend.”)

But the Cruising Pavilion also treats its thesis with earnestness — presenting the ways in which LGBTQ people have shaped space and the ways in which architecture has therefore in turn shaped space for them.

One small installation is an examination of the ways in which public toilets have been designed and employed by the public over time. Another presents the architectural schematics for a gay club called the Boiler in London designed by Studio Karhard. There is also an experimental examination of glory holes.

End of the party

But the nightclub setting keeps things feeling appropriately risqué. Dim lighting makes it difficult to spend too much time reading the presented texts. And Dawson’s moans (he of the busy weekend) echo throughout the gallery — which keeps the whole affair from getting too egg-headed. This is about the human desire for sex after all.

Which is ultimately what makes the Cruising Pavilion an engaging all-encompassing work of art.

In their statement, the curators note that social media apps such as Grindr have begun to supplant the physical spaces once apported to cruising. And gay bars and other queer social spaces have been in decline.

Cruising Pavilion highlights the importance of tangible, physical space — space in which humans could connect without a technological intermediary.

On my way out, as I walk through a dark and empty central gallery, I wonder why the curators hadn’t thought to install anything in that space — until I realize I am stepping on something. I turn on my phone light and discover all manner of detritus: condoms, crumpled tissues and pieces of clothing that seemed to have been hastily shed.

Whatever went down in this space — or the many spaces that it evokes — it had been one excellent party.

ALSO

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.