How a Bay Area-raised critic captured ‘the banal ecstasy of friendship’

On the Shelf

Stay True: A Memoir

By Hua Hsu

Doubleday: 206 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

ANNANDALE-ON-HUDSON, N.Y. — We had to keep dodging the rain.

I’d met Hua Hsu at Bard, the liberal arts college in Annandale-on-Hudson, and the weather made it impossible for us to sit still as we talked about his memoir, “Stay True.” In the book, Hsu, a brilliant, delightfully obsessive cultural critic on staff at the New Yorker, traces how he came to think about music and community, from his Cupertino childhood through college.

At Bard, the weather drove us inside and out, from his office to benches and tables and porticos. Students flowed around us in cohesive packs. They’d only recently arrived on campus, but before school, they’d been connected online with their classmates. “They all presorted who’s into what,” Hsu explained. The young Gen X-er’s experience at UC Berkeley was basically the opposite; he found his friends the analog way — through other friends, coincidence, physical proximity.

For Hsu back then, the music you liked or the vintage sweater you wore were vital signifiers. “You could only project a limited amount of yourself into the world and you really tried to make it count,” he says. But that was him; his friends didn’t care so much. His friend Ken, for example, listened to the desperately uncool Dave Matthews Band while Hsu’s alternative bona fides started with his youthful adoration of Nirvana. If they were to start college today, Hsu might have stuck to his tribe of music geeks and never met Ken, a genial frat boy.

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

But they became the closest of friends, part of a small group who met each others’ families, teased and helped each other, drove around together listening to music because there was so much time. Then, the summer before senior year, Ken was murdered in a senseless robbery. Hsu was devastated. “I picked up a pen,” he writes in the book, “and tried to write myself back into the past.”

From the time he was young, Hsu labored over zines and tried to engage with culture and the world through writing, but he sees Ken’s death as his birth as a writer. Struggling with grief, he found power in writing things down. “I became fixated on writing as a path out, as a way of reconciling,” he told me.

The book advances chronologically, allowing Hsu to tell Ken’s story as they lived it. “Once I figured out that a book about the tragedy could also be a book about fun, dumb college stuff, or the banal ecstasy of friendship, I was like, ‘Cool,’” he said. It’s been 24 years since Ken died, and sometimes writing those passages was like spending time with him again. “I don’t think I realized until I was older that part of what I had to do was also hold on to the happy times, the good times, the joy.”

He is, of course, aware of the irony that there would have been no need to atomize these college moments if Ken hadn’t been killed. “I would’ve never had any reason to remember any of these things — because if he were still alive, we would’ve just had more experiences that sedimented on top of them.” Hsu’s own experiences, and those of his core group of friends, continue on for the last third of the book, including an indelible section on the funeral.

The imprint of his friends is there, invisibly. They all read parts of drafts. “I don’t want the emotional center of the book necessarily to be my experience, even though it’s my story,” he says. Although they are anonymized in the memoir, these friends would fall under the broad census category of “Asian.” Hsu is the son of immigrants from Taiwan; Ken was from a Japanese family that had long been in the U.S. The publisher emphasizes their heritage in the publicity materials.

My family came from England generations ago, so I apologized to Hsu for not being able to engage around these issues with any standing. He was gracious about it. We had plenty of other things in the book to discuss: grief, the band CAN, California, postmodernism.

So I asked him about Jacques Derrida. I can see why a publisher might not want to emphasize a notoriously incomprehensible linguist and literary theorist on the back jacket, but Hsu found a legible way to bring Derrida into his memoir. A series of Derrida’s lectures was published as the book “The Politics of Friendship,” which includes a eulogy for Jean-Francois Lyotard.

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

“Derrida, people generally think, is hard to understand,” Hsu said, “but when thinking about friendship, about Lyotard, about the final stretch of his own life, there’s so much clarity and so much grace to the way he was writing.”

Nor was the allusion incidental to Derrida’s style or ideas. “When I was writing the book, there are these digressions — I don’t know if they’re digressions,” Hsu said (digressively), “but there are these moments where Derrida shows up, Marcel Mauss shows up.” Hsu brings in these French thinkers to underscore the kind of concepts he was encountering in college, while also gesturing toward what underlies the text you’re reading; in many ways, the book is a portrait of the public intellectual as a young man.

Hsu, who has a PhD from Harvard in American studies, has a capacious intelligence wrapped in a chill vibe. He says “like” a lot, so much that it often appears several times per sentence (such verbal placeholders are edited out for clarity). Maybe it was growing up in California. “I still have that kind of disposition where people think I’m stoned a little bit,” he said.

“California, at least when I was growing up, was a very diverse, liberal place. It’s where people wanted to go. Everyone felt like we had won because we grew up in California.” He mentions the beach, then laughingly admits he never went to the beach. But lately, when he teaches classes on urbanism, his students want to write about Los Angeles.

Hsu’s office at Bard is packed full of books and music and magazines and ephemera: baseball bobbleheads, old tape players, ‘90s stickers, a prototype 50 Cent Vitamin Water. But when I was there, it didn’t have a lick of furniture. Hsu just moved to Bard (he taught previously at Vassar College) and his first class will be in the spring; he doesn’t have a desk or chairs yet.

“This is where I keep a lot of things that I don’t feel like I should throw away yet, but I have no use for. Like my old college skateboard,” he said. “But I feel like I never left college in a way, so it makes sense to have these things still.”

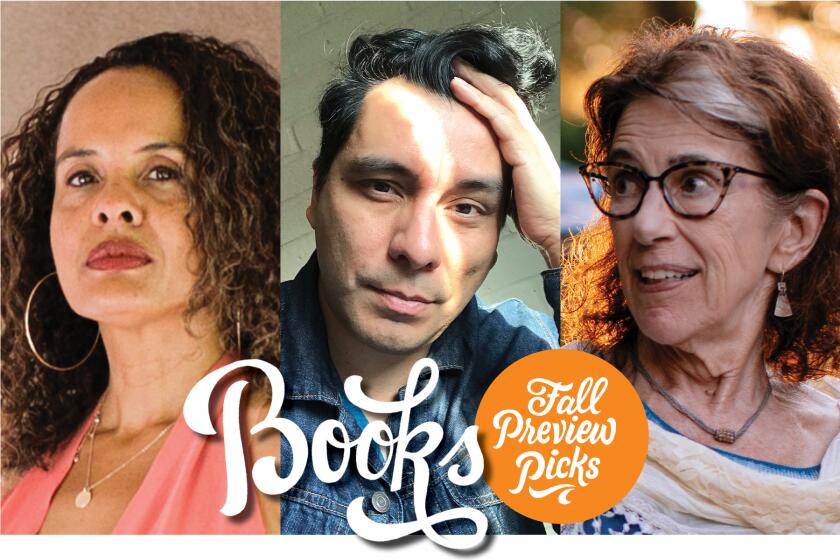

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

Kellogg is a former book editor of The Times. She can be found on Twitter @paperhaus.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.