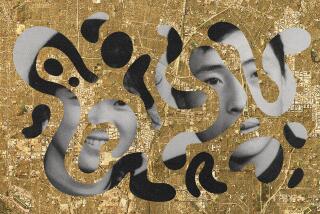

From O.C. church shooting to Pelosi’s visit — what it’s like to be Taiwanese American right now

At the Miss Taiwanese American pageant, contestants usually answer questions like, “Describe yourself in three words.”

This year, with the competition taking place days after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s controversial visit to Taiwan, organizers prodded the young women to share their thoughts about the island.

One contestant, Tiffany Chang, highlighted Taiwan’s vaunted semiconductor industry and a democratic government that provides universal healthcare and has legalized same-sex marriage.

Chang said afterward that she has become increasingly conscious of her role in educating others about Taiwan, as China’s threats grow more aggressive.

“If we as Taiwanese Americans don’t define our identity, it will be imposed on us, as Taiwan’s history reminds us again and again,” said Chang, an incoming first-year student at Stanford, who was crowned the winner Aug. 6 at the Hilton hotel in San Gabriel.

Taiwan’s complex geopolitical and ethnic history came to the nation’s attention in May after a gunman opened fire on a Taiwanese church congregation in Laguna Woods, killing one and wounding five.

As details emerged about the Taiwan-born suspect and his political beliefs, Taiwanese Americans found themselves explaining a subject that takes paragraphs, not sentences, to get straight. Some who grew up in the U.S. realized they needed to learn more themselves before answering friends’ questions.

Last month, Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan forced the world to notice the precariousness of the island’s existence.

China’s furious response could drive more Taiwanese toward independence and push neighboring Asian nations to strengthen their defense strategies.

How was Taiwan de facto independent, with its own military and democratically elected government, yet China was trying to call the shots? Would the U.S. come to Taiwan’s defense if China attacked? Were people in Taiwan scared? (No, they were mostly concerned about what to have for dinner — and what Pelosi ate while she was there.)

In Southern California’s Taiwanese immigrant community, some thought Pelosi brought needed attention to their homeland, while others viewed the trip, which prompted China to fire missiles and fly fighter jets near Taiwan’s coast, as dangerous grandstanding.

Among Taiwanese, ideological divides are as stark as red and blue in American politics, with friends often agreeing to steer clear of sensitive subjects. Some elders speak Japanese better than Mandarin, while others recall fleeing from the Japanese in mainland China during World War II. Some call themselves Taiwanese. Others prefer Chinese. Some want to push more openly for independence.

Most everyone, though, can agree on one thing: They support Taiwan’s democratic way of life and don’t want China, which considers the island part of its territory, to take over by force.

“It’s like two brothers in the same family, running the family business but they don’t see eye to eye,” Prudence Huang, 63, of Long Beach said of divisions among Taiwanese immigrants. “I just hope before I die, Taiwan and China can have a peaceful solution — without war.”

Huang, a retired database administrator who came to the U.S. four decades ago, usually avoids discussing Taiwanese politics. But an online group chat grew heated when she questioned why Taiwanese citizens would pay for a “Taiwan for Trump” billboard during the 2020 election.

“They immediately labeled me pro-China, and I didn’t even mention China at all,” said Huang, who holds dual U.S. and Taiwanese citizenship.

Janet Chu, a medical office clerk in the San Gabriel Valley, said Pelosi’s visit shone a needed spotlight on Taiwan.

It was the first time a House speaker had set foot in Chu’s homeland since Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) in 1997, though congressional delegations often visit.

Until Pelosi (D-San Francisco) made headlines, many of Chu’s friends had little interest in Taiwan, preferring to travel to China or Japan.

“Mrs. Pelosi is putting positive attention to our country,” Chu, who moved to California from Taipei, Taiwan’s capital, in the 1980s, said as she waited for a table at ZZ Hotpot House in Garden Grove. “She can choose to travel to anywhere. I’m happy she chose Taiwan, because we need the public to have sympathy for our situation.”

In West Los Angeles, Crystal Kaza, who immigrated to the U.S. in 1991, had a starkly different view of Pelosi’s trip. She wondered whether Pelosi was angling for publicity rather than trying to help Taiwan.

“When I see us in the news, my first question is, ‘What’s the purpose?’ People talk about Taiwan as if they really understand its history and all the nuance,” said Kaza, 53, a substitute teacher. “But until you live it, you can’t judge.”

More than 50,000 Taiwanese Americans live in Southern California, according to AAPI Data’s June analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. This is likely a significant undercount because some mark their ethnicity as Chinese.

Beginning in the 1960s, students from Taiwan enrolled in U.S. graduate schools, often to study science or technology, said Chris Fan, an Asian American studies professor at UC Irvine.

Many stayed to build careers and raise families. The immigrant pool later became more diverse, but Taiwanese Americans remain among the most highly educated and wealthiest ethnic groups in the country, Fan said.

Older Taiwanese immigrants are defined by their identities as waishengren — those who fled from mainland China around the time the Nationalists lost to the Communists in 1949 — or benshengren, who had settled in Taiwan before then, said Wendy Cheng, a Scripps College professor of American studies.

Subsequent generations are more likely to identify as Taiwanese, no matter their ancestry, Cheng said — as is the case among younger people in Taiwan.

At the Taiwan Center in Rosemead recently, members of the karaoke club belted out songs.

John Huang, a retiree from Arcadia, sang “Minato Machi Blues” in Japanese.

At 84, he was born under Japanese colonial rule. After Chiang Kai-shek’s repressive government took over, he was forbidden to speak the Taiwanese dialect at school.

Huang, who came to the U.S. in 1975 and worked as an interior designer in Beverly Hills, taught his two children to speak fluent Taiwanese.

“Long time ago, they said we are Chinese because they controlled everything,” he said. “They know everything is Taiwanese” now.

A day later, Lillian Chang arrived at the center to pick up her award for being named first princess in the Miss Taiwanese American pageant.

Chang, 26, is a satellite structures engineer from Torrance who moved to the U.S. as a teenager. Quite a few co-workers have asked her about Taiwan lately.

“I just told them, ‘We are doing our job to spread democracy,’” she said. “So if you can help, that would be good.”

Perspectives vary on each side of the Pacific, Chang has realized, with distance magnifying fears about loved ones.

After the church shooting, Chang’s parents called from Taiwan to express concern about gun violence and hate crimes. She promised to hide in her car, if needed, adding that she had gone to a shooting range to familiarize herself with a gun.

Prosecutors have not yet filed a hate crime sentencing enhancement against David Wenwei Chou, accused of shooting six people, one fatally, in Laguna Woods.

Many in Taiwan, used to decades of threats from China, reacted nonchalantly to Pelosi’s visit. Chang reminded her mom and dad to put together an emergency backpack to take with them should things turn bad.

“They haven’t,” she said. “Which worries me.”

The events of the last year have forced Taiwanese Americans to confront their history and internal divisions — potentially drawing them closer together, said Chieh-Ting Yeh of Mountain View, Calif., who co-founded the Taiwan-focused Ketagalan Media.

Whatever their ethnic backgrounds, many can agree on the common cause of “defending democracy, freedom, human rights, especially against China,” said Yeh, who came to the U.S. from Taiwan when he was 10.

“People realized, no matter what our internal differences may be within the Taiwanese identity, there is something that we need to fight off,” he said.

To be Taiwanese American right now is to constantly check the headlines, “trying to read everything people are saying about us,” said Alan Chang, 26, sipping a sea salt coffee at the Taiwanese bakery 85C in Irvine.

Chang has friends whose parents came from mainland China, along with those like him with roots in Taiwan. They haven’t delved much into one another’s backgrounds.

Chang, who works part time for a driving service, is not registered to vote, and Pelosi’s visit caught him by surprise. He assumed that American politicians would mainly pay attention to domestic issues.

“I didn’t understand the implications of her trip, because I’ve never been to my parents’ homeland,” he said. “Guess it’s time to learn more now. It made me curious to start talking to them about how they grew up.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.