Jacques Derrida, 74; Intellectual Founded Controversial Deconstruction Movement

Jacques Derrida, the influential French thinker and writer who inspired admiration, vilification and utter bewilderment as the founder of the intellectual movement known as deconstruction, has died. He was 74.

Derrida died Friday at a Paris hospital of complications from pancreatic cancer, French radio reported.

“With him, France has given the world one of its greatest contemporary philosophers, one of the major figures of intellectual life of our time,” French President Jacques Chirac said in a statement Saturday. “Through his work, he sought to find the free movement which lies at the root of all thinking.”

Derrida, who divided his time between Paris and the United States, where he lectured annually at UC Irvine and other universities, was perhaps the most controversial and daring philosopher of the late 20th century.

He rocked the American academy in a 1966 speech that introduced deconstruction to the United States as a mode of analysis that sought to turn Western philosophy on its head.

Deconstruction gained a following on college campuses across the country, most famously at Yale University in the 1970s and later at UC Irvine. A notoriously difficult theory, it left an imprint on a number of fields, particularly literature, where scholars seized on deconstruction as the basis for radical reinterpretations of classic works of literature and philosophy. Gradually, disciplines as disparate as business, architecture, law and religion showed the influence of Derrida’s ideas.

Although deconstruction’s influence has waned, it even penetrated popular culture, where the avant-garde in seemingly everything from couture to cuisine has been described, rightly or wrongly, as “deconstructed.”

“Of all the philosophers of our time,” eminent Stanford University philosopher Richard Rorty once said, Derrida “has been the most effective at doing what Socrates hoped philosophers would do: breaking the crust of convention, questioning assumptions never before doubted, raising issues never before discussed.”

His detractors were just as vociferous. Some labeled him a nihilist for his subversion of traditional principles, while others charged him with deliberate inscrutability.

John Searle, a Mills professor of philosophy at UC Berkeley and one of Derrida’s most eloquent critics, once said that what he found most deplorable about Derrida and deconstruction was “the low level of philosophical argumentation, the deliberate obscurantism of the prose, the wildly exaggerated claims, and the constant striving to give the appearance of profundity by making claims that seem paradoxical, but under analysis often turn out to be silly or trivial.”

Critics saw nothing silly about Derrida’s defense in the late 1980s of Paul de Man, a Yale professor and a leading American proponent of deconstruction who had died earlier that decade. Derrida issued a 60-page essay supporting De Man after reports that De Man, a native of Belgium, had written for a pro-Nazi Belgian newspaper in the early 1940s. Derrida’s critics seized on his defense of De Man as evidence of deconstruction’s apolitical and nihilistic nature.

In 1992, when Cambridge University proposed giving Derrida an honorary degree, the anti-Derrideans on the faculty raised strenuous objections, pronouncing his work “absurd,” “disabling” and so perverse as to “make complete nonsense of science, technology and medicine.” Their dissent triggered the first full faculty vote on an honorary degree in 30 years, but Derrida’s supporters prevailed, 336 to 204.

Stimulating, Stupefying

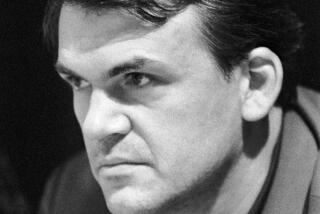

The father of deconstruction was a dapper man with a dark Mediterranean complexion, bushy brows and a fluffy crown of white hair. The subject of rock paeans and guidebooks with names like “Derrida for Beginners” and “Derrida in 90 Minutes,” he packed lecture halls with erudite audiences, who were alternately stimulated and stupefied by his arcane ramblings, which often lasted hours.

The author of more than 50 books, he tended to convey his ideas in the most confounding language possible, playing with words and writing sentences that ran two or three pages long. Critics declared some of his essays and books unreadable. But what some found unfathomable others extolled as embodying the elusiveness of meaning, a central tenet of Derridean thinking.

Derrida rarely satisfied those who sought a straightforward explanation of deconstruction. When asked by the New York Times some years ago for a definition, he declined, saying the attempt would only result in “something which will leave me unsatisfied.”

Other times he was more willing to explore, rather than close, the cognitive abyss. Handing out copies of a particularly confusing poem to an audience in Irvine a few years ago, he said he wouldn’t even attempt to explain the poem, but he would explain why he wouldn’t explain it.

On another occasion, he wrote: “What deconstruction is not? Everything, of course! What is deconstruction? Nothing, of course!”

What perturbed many of his critics was deconstruction’s focus on picking apart a text, finding the ambiguities and contradictions, and “deconstructing” them until the surface meaning collapsed.

His famous assertion that “there is nothing outside the text” meant that such traditional considerations as historical context and an author’s intent were secondary, at best, in the search for the text’s meaning.

His approach strove foremost to show that “the text never exactly means what it says or says what it means,” critic Christopher Norris wrote. And a text, according to Derrida, could be any cultural product, from a Shakespeare sonnet to a building by architect Frank Gehry.

Derrida’s own focus was on philosophical texts by such giants as Plato, Rene Descartes and Jean Jacques Rousseau. He liked to say he operated in philosophy’s margins, looking for the false polarities that he argued undermined Western logic.

He was reluctant to reveal much about his life, fearful of biographers’ efforts to find cause and effect between his personal history and his public views. Yet the links were difficult to deny.

Derrida was born in Algiers in 1930, the fifth generation of his family of assimilated Sephardic Jews to be raised in Algeria.

Although his life was comfortably middle class, his early years were fraught with tragedy and crisis. Two brothers died in childhood, causing his mother to panic whenever Derrida showed signs of illness.

In 1940, when he was 10, the Nazi collaborationists who ruled French Algeria imposed quotas on Jewish school enrollment, and Derrida, the top student at his academy, was expelled. A teacher said French culture was “not made for little Jews.” He and his family were stripped of their citizenship.

Although he acknowledged that the anti-Semitism he encountered in Algeria was nowhere near as oppressive as that in Europe, it enforced his view of himself as an outsider. “When you are expelled from school without understanding why, it marks you,” he acknowledged in a 2002 L.A. Weekly interview.

Derrida spent an unhappy interlude in an unofficial Jewish lycee in Algiers until the end of World War II, when normality returned to the schools. Often truant during the war, he continued to pay little attention to his studies, dreaming instead of becoming a professional soccer player.

According to biographer Paul Strathern, Derrida’s interest in philosophy was piqued when he heard a talk about Albert Camus. Soon Derrida was reading French writer Andre Gide and poet-philosopher Paul Valery and filling a diary with quotations from Friedrich Nietzsche and Rousseau. Near the end of high school, he began to read Jean-Paul Sartre.

Although his grades were poor, his intellectual ability was undeniable: He was sent to Paris to study for entrance to the Ecole Normale Superieure, France’s most prestigious college. He was admitted in 1952 and plunged into his formal study of philosophy.

He met his future wife, Marguerite Aucouturier, at the Ecole Normale. A psychoanalyst, she and Derrida were married in 1957. She survives him, along with their sons, Pierre and Jean.

After graduating in 1956, Derrida spent a year at Harvard University on a graduate scholarship, then returned to Algeria to serve in the French army as a teacher.

Plagued by ‘Nostalgeria’

He moved back to France in 1960 to teach philosophy and logic at the Sorbonne, but hoped one day to become a citizen of an independent Algeria. However, when the French colony finally won its independence in 1962, Europeans left en masse and Derrida realized that he would not be welcomed back. He suffered what Strathern described as a “severe depressive episode.” From this time on he would refer to his sadness as “nostalgeria.”

The same year that Algeria broke free from France, Derrida published his first important work: a French translation of German philosopher Edmund Husserl’s “Origin of Geometry,” for which he wrote a book-length introduction.

Husserl had argued that geometry began with human intuition about such basic concepts as line and distance. But the rest of geometry, he asserted, was independent of human experience -- its rules and operations timeless truths just waiting to be discovered.

Derrida questioned the German thinker’s logic. How could geometry owe its creation to intuition and yet be independent of intuition? Derrida argued that Husserl could not have it both ways. Building on the ideas of Martin Heidegger, he seized on what philosophers call an aporia, an internal inconsistency without solution. His reasoning called into question the whole notion of absolute truth, the basis of Western philosophy.

Derrida’s critique laid the foundation for deconstruction, which seeks out the hidden assumptions and conflicts that undermine truth. It also shed light on his view of himself as an “anti-philosopher,” whose role was “an interrogation of [philosophy’s] very possibility.”

By 1965 Derrida was teaching the history of philosophy at the Ecole Normale Superieure and was associated with Tel Quel, a leftist magazine that published work by such thinkers as Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault. Derrida shared with them the desire to overturn conventional perceptions of writing, literary criticism and philosophy.

In 1966, Derrida addressed a symposium at Johns Hopkins University during which he took issue with the philosophical and critical movement called structuralism, which held that all meaning stemmed from “deep structures” found in a society’s myths -- structures through which the society defined itself. He argued that what he would later call deconstruction was a better lens through which to view important cultural works.

“He was reading texts by Rousseau, Plato and [French poet Stephane] Mallarme and seeing things nobody ever saw,” J. Hillis Miller, a Johns Hopkins English professor who missed Derrida’s lecture but read a transcript soon afterward, told The Times some years ago. Miller was heavily influenced by Derrida’s work and became a leading deconstructionist at Yale.

The year after his Johns Hopkins address, Derrida signaled his arrival as a major new thinker with the publication of three seminal volumes: “Writing and Difference,” “Speech and Phenomena” and “Of Grammatology.”

“Of Grammatology,” his most famous work, focuses on the submerged dualisms and hierarchies that Derrida considered the foundation of Western thought. He said that embedded in any text were oppositional pairs such as good/evil, mind/body, male/female, truth/fiction. He further said that the first term in any set of such “binary opposites” is valued or privileged over the second. It is these oppositions, Derrida argued, that must be deconstructed.

“All metaphysicians, from Plato to Rousseau, Descartes to Husserl, have proceeded this way,” he wrote, “conceiving good to be before evil, the positive before the negative, the pure before the impure, the simple before the complex, the essential before the accidental, the imitated before the imitation, etc. And this is not just one metaphysical gesture among others, it is the metaphysical exigency, that which has been the most constant, most profound and most potent.”

To illustrate how the greatest philosophers contradict themselves, he often cited Plato’s declaration that oral discourse “is written in the soul of the listener.” If speech, as the father of Western thought asserted, was superior to writing, how could it then be “written” in the soul?

Like a Freudian slip, Plato’s choice of words undercut his own argument, Derrida insisted, demonstrating that speech is not more authentic or closer to truth than writing.

In fact, Derrida believed that pairs such as speech/writing were not absolute opposites but linked, as accomplices, so that one had no meaning without the other.

In exposing such false polarities, Derrida aimed to illuminate alternative or suppressed meanings, a process not dissimilar to a psychoanalyst’s dredging of the subconscious. The deconstructionist reader shuns the idea that a text can have a single, authoritative meaning. Most texts, Derrida asserted, have too many meanings, a condition that he called “undecidability.”

“Deconstruction is a way of remembering what our culture is made of,” he told the Times of London some years ago in one of his more cogent statements, “a way of reanalyzing, for instance, what philosophy is. It is not simply a matter of theory, but of analyzing the different layers and assumptions of Western philosophy.” What was the point of all this? Nothing good, Derrida’s critics said.

“Derrida’s influence has been disastrous,” Roger Kimball, a conservative critic, said in a 1994 New York Times Magazine interview. “He has helped foster a sort of anemic nihilism, which has given imprimaturs to squads of imitators who no longer feel that what they are engaged in is a search for truth, who would find that notion risible.”

To others, particularly literature professors, deconstruction was a powerful and subtle tool.

“It was a little like the moment when Helen Keller first understands the connection between the signing she is being taught and meaning,” Barbara Johnson, a prominent deconstructionist and feminist critic who teaches English at Harvard, said in a 1991 interview about her first encounter with Derrida’s ideas. “Keller wanted to go back and sign everything; I wanted to reread everything.”

Strong Impact at Yale

Deconstruction’s impact was particularly strong at Yale, where Derrida became a lecturer in the 1970s and heavily influenced the “Yale school” of critics -- a group that included Miller, De Man, Geoffrey Hartman and Harold Bloom.

The scholarly center of deconstruction later shifted to UC Irvine, which recruited Miller in 1986. Later that year, the university scored a greater coup with Derrida, who became a professor of humanities there. He taught at Irvine one quarter a year until the spring of 2003, while maintaining his post as professor of philosophy at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Science in Paris, where he also served as director.

“Our community is deeply saddened to learn of the death of Jacques Derrida,” Karen Lawrence, dean of humanities at UC Irvine, told The Times on Saturday. “The world has lost one of the most original and provocative thinkers of the 20th century.”

What may have been most threatening about deconstruction was its embrace of disorder, of the view that the world is not a simple place, reducible to such absolute concepts as good versus evil, hero versus villain, sane versus insane.

“I think that people who try to represent what I’m doing or what so-called deconstruction is doing as, on the one hand, trying to destroy culture or, on the other hand, to reduce it to a kind of negativity, to a kind of death, are misrepresenting deconstruction,” he once told an interviewer.

“Deconstruction is essentially affirmative. It’s in favor of reaffirmation of memory, but this reaffirmation of memory asks the most adventurous and the most risky questions about our tradition, about our institutions, about our way of teaching, and so on.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.