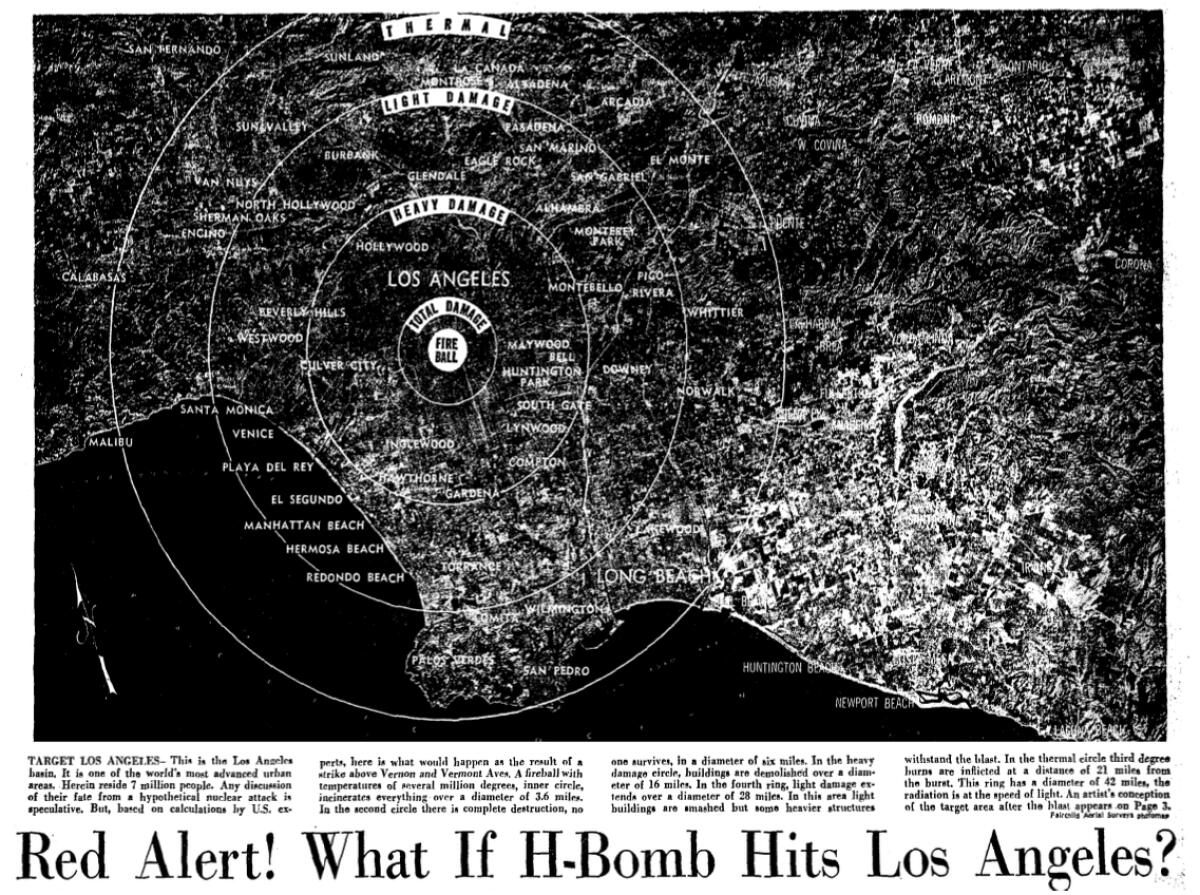

Cold War L.A. could have been a nuclear target. One response: the fallout shelter

You know Angelenos and real estate: If someone’s selling it, we’ll buy it, even if it’s underground.

Long before “da bomb,” there was “The Bomb.” The first is a now-obsolete descriptor for “cool.” The second is a real WMD, not remotely cool, and not remotely close to obsolete.

Because of the capital-b Bomb, Southern California, ever the groundbreaker, once had a fine obsession with that quirky Cold War amenity: the backyard bomb shelter, a thermonuclear version of that time-share you never end up using.

Today, as the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists sets the hands of its doomsday clock to an ominous 100 seconds to a nuclear midnight, maybe those hidey-holes are starting to look pretty good, although truth to tell, they were probably a bit more performative Cold War theatrics than actual protection. As a Los Angeles musician of note once noted, “no one here gets out alive,” or at least unscathed.

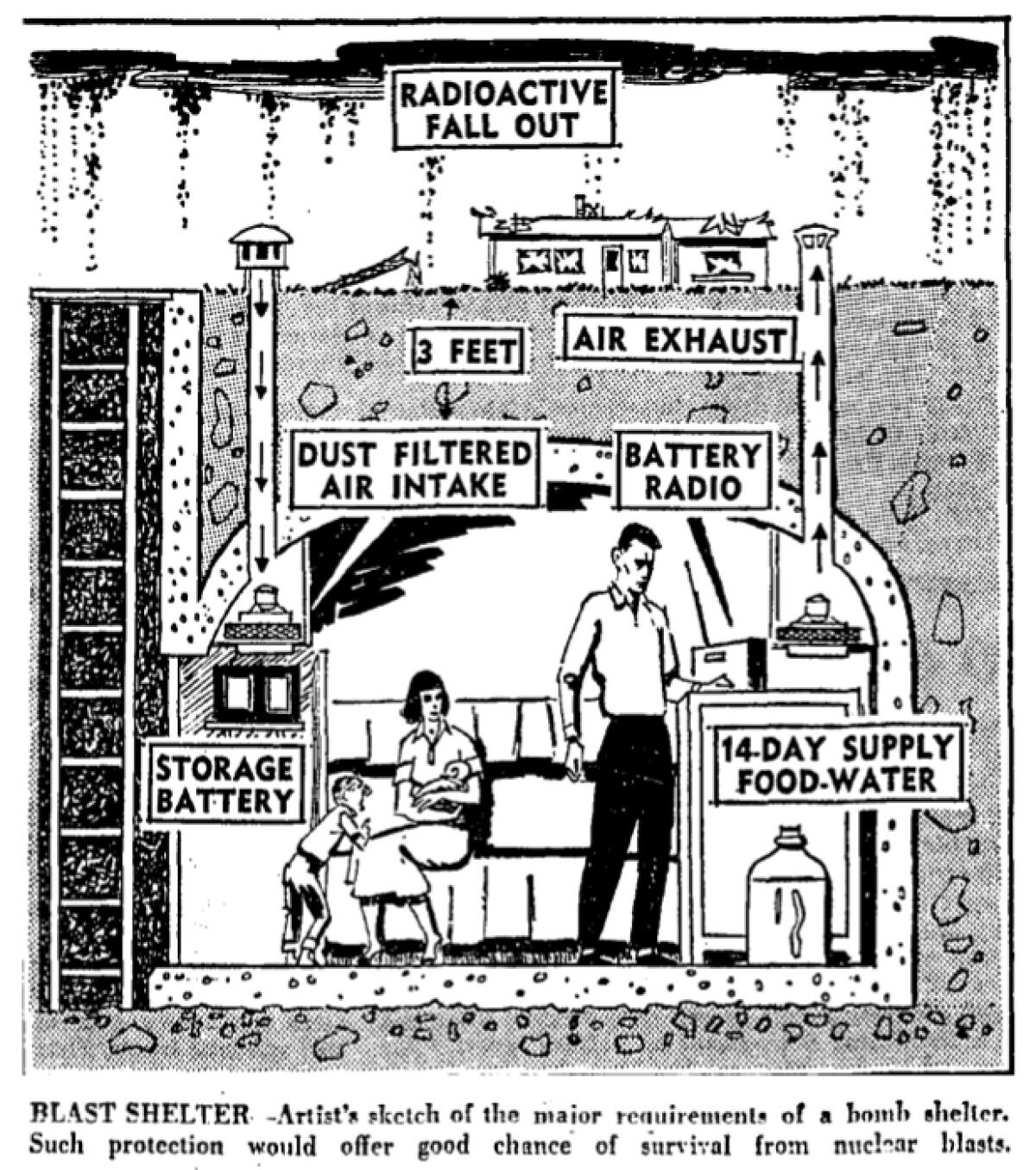

Anyhoo, matters seemed simultaneously scarier and more chipper in the ’50s and ’60s when it came to nuclear survivability-think. From the end of sizzling World War II through the Cuban Missile Crisis and until almost the defrosting of the Cold War, federal and local governments, along with any number of doomsday entrepreneurs, promoted the bomb/fallout shelters as something no family should be without.

“The home fallout shelter,” opined Joseph J. Micciche, L.A.’s civil defense director, “is the only means of survival in the event of nuclear attack.” As late as 1982, President Reagan’s deputy undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, Thomas K. Jones, a stalwart believer in civil defense programs, was completely sincere when he said, “If there are enough shovels to go around, everybody’s going to make it.”

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

To Commie nuke-planners, Southern California — which had invested for decades in aviation, defense and aerospace — wore a big target. That may have accelerated shelter anxieties.

In May 1960, a Los Angeles company switched from making trampolines to making metal fallout shelters, sending salesmen door to door to peddle the $1,500 prefab metal model, without, of course, setting off little bombs as the traveling salesman’s standard home-test demonstration.

A Pomona company sold the Fox Hole Shelter, an igloo-shaped shelter installed in one day and guaranteed to withstand an atomic blast three miles away — secure, perhaps, in the certainty that dissatisfied customers would not be around to demand a refund on the warranty.

The renowned architect Wallace Neff built a bubble-shaped underground shelter for his renowned “Bubble House” in Pasadena, where one post-Cold War owner would retreat for primal-scream therapy and guitar jam sessions.

In Redondo Beach in 1951, a contractor got permits to build two shelters: one at his own home, with room enough for six, and another for a house he rented out.

A 1964 Covina estate, where some descendants of the founder of the Singer sewing machine company liked to summer, gloried in a koi pond, an aviary and a 10-bed bomb shelter.

In September 1961, up in Benedict Canyon, a family man built a “subterranean castle” beside the swimming pool. It was fitted out with radio, phone, TV, and Geiger counter, and capacious enough for 15 people to spend 30 days. Those people were the mister and missus, their three young children, their three married children and grandkids (if they could get there before the hatch was sealed), four servants, and a collie, a Pekingese and a miniature bulldog.

Late in the 1960s, the people of Victorville brought pickaxes and shovels to dig a capacious shelter deep in an abandoned mine shaft. They stocked it with medical supplies, food and water for three weeks, a record player, seeds, and more than a thousand books. The local civil defense coordinator, William C. Melton, admitted that Victorville was not likely a prime bomb target: “The only reason there would ever be a nuclear strike in Victorville is if the enemy were 100 miles off his mark.” There was room for 1,100 people, first come, first served. (A Facebook page for the Mojave Desert Cultural and Heritage Assn. notes that “vandals and thieves” soon stole or smashed or set fire to just about everything on the premises, and that “barely a scar” remains to mark its place as a large step toward closing the dreaded Strangelovian “mine shaft gap.”

In Monrovia, a civil engineer who had survived the London blitz built what he called “a life house,” with a door of lead and laminated wood, and a small generator powered by a stationary bike that doubled as exercise for the shelter-bound. “A good, well-planned underground shelter is a must for everyone these days.”

My fave might be a 1950s WeHo-adjacent estate, back on the market a couple of years ago, that’s tricked out with what The Times described as winding “indoor-outdoor lagoon” leading to an underwater tunnel through which one reaches the bomb shelter — “a secret, sealed underground cave aerated with oxygen tanks.” In other words, you had to swim to be saved.

Each was built not only with the faith that it would survive an initial blast, but that in due course — days, weeks, or months — the sheltered could emerge to pick up life such as it was in a post-nuke world.

Rather stupefyingly, The Times printed the addresses of these newly defensible dwellings. What neighbors might not consider banging on a shelter door when the nuclear sirens sounded? Ministers spoke from their pulpits about the ethics of bomb shelters: Was it moral to add guns to the supplies of canned food and toilet paper? “The Twilight Zone” aired an episode in 1961 about a shelter setting neighbor against neighbor as the missiles were inbound.

An arguable bomb subculture presented itself. Novelists Joyce Carol Oates and John Cheever built bomb shelters into their fiction. A Times financial advice columnist in 1961 tackled the question: Are fallout shelters good investments? (Like such columnists before and after, the answer was: It depends.) Wedding-shower guests gift-wrapped imperishable bomb-shelter food like beans and crackers. A newlywed pair in 1959 Florida did take a dare from a radio station and spent their two-week honeymoon underground, where the radio station and her parents called them up too many times a day. They emerged wanting ice-cold water, baths, and steaks, and eager for their prize: a two-week honeymoon in Mexico. They remained married until a natural death, not a nuclear one, did them part 42 years later.

Yet Southern Californians still kept digging far more holes for swimming pools than for shelters. In mid-1960, the Gallup poll found that 71% of Americans wanted shelters, all right — but they wanted government-built and -run shelters. More than a third were interested in personal shelters, so long as they cost no more than $500, but half gave them a full pass.

Los Angeles County was then considering turning storm drains into bomb shelters, a project code-named “Operation Big Ditch.” The city of L.A. did end up designating more than a thousand public fallout shelters, mostly basements or interior rooms of government buildings, and it kept on its payroll full-time inspectors to make sure they were all up to snuff.

The last of these inspectors worked, alone, at least into the 1970s, with a confounding list that named the shelters alphabetically, not geographically. His inspections found that the “no-expiration” shelter crackers had turned rancid and “tasted like hell,” and what narcotics hadn’t been stolen were officially removed. The stock of diarrhea medicine had settled into a “thick, chalky glob” that wouldn’t come out of the bottle.

In 1961, not long after President Kennedy admitted he’d been “savaged” by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at a summit, a Johns Hopkins psychiatry professor told us to stop worrying — not about the bomb, but about bomb shelters. “We are a great people for fads. Remember how the hula hoop swept the country? And the yo-yo? Well, right now it’s the thing to do to talk about building a fallout shelter. Among my personal acquaintances, however, I know very few who have gone beyond the talking and have actually built shelters.”

Now and again, one of them still turns up in these parts. In 2013, a Woodland Hills family discovered in its new home the evidence of an earlier family: a well-stocked fallout shelter built in the 1960s, about 15 feet underground, by a self-taught nuclear engineer whose daughter had recently sold the house and remembered the shelter very well.

Such unearthings happened often enough that Hollywood tweaked this into a 1998 movie called “Blast From the Past,” about a grown man who had lived entirely in a shelter with his parents, until he emerged into the modern-day San Fernando Valley, a shock enough for anyone’s system.

California hasn’t executed any prisoners since 2006, and Gov. Newsom has ordered San Quentin’s death row dismantled.

The shelters were only a part of the civil defense network. Within weeks of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, Los Angeles bought scores of air-raid sirens, some shaped like rockets, some shaped like trumpets, or birdhouses, and mounted them above fire stations, on telephone poles, at Griffith Park observatory. The warbling sound meant “attack imminent,” the steady note “all clear.”

Even back then, people complained that they were ineffective. The sound was too faint, and too much like police or fire sirens, or car horns. The Times groused in 1952 about the “pipsqueak sirens … what we need are some really LOUD alarms that will make a distinctive noise and all but wake the dead.”

Anyone who worked in downtown Los Angeles before 1985 will remember that at 10 o’clock in the morning, on the last Friday of the month, someone in the sheriff’s office flipped a switch or pushed a button, and the geriatric siren system tested its vocal cords, rising from a menacing growl to a slow warble. There weren’t many decibels left in the old network; wires had corroded and cable sheathing had become rat snacks, and in 1985, L.A. County shut the whole thing down. There was talk of reviving it in 2003 at the start of the Iraq war, but the technology had by been surpassed. (No technology is modern enough to be foolproof, emphasis “fool.” On a Saturday morning in January 2018, Hawaiians awoke to the cellphone alert “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” It took 38 minutes and 13 seconds for the state to walk it back.)

In the end, it wasn’t peace or price that made the bomb shelter more an object of discussion than of construction.

At the same time civil defense agencies were pushing Americans to build shelters, Congress wouldn’t give tax deductions for the cost of them. And the last straw, smack-dab in the middle of the Cold War? When the Orange County tax assessor, like those in other counties, ruled that you had to pay property tax on your bomb shelter.

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.