Before Pearl Harbor, L.A. was home to thriving Japanese communities. Here’s what they were like

You know the date — Dec. 7 — and what happened then, and what happened thereafter, to the United States and to the world.

But what was life like on Dec. 6, 1941, and in the years before then, closer to home, for one group of people for whom that date would alter their lives — the Japanese and Japanese Americans in Los Angeles?

For the many thousands of them living on the West Coast — among them U.S. citizens — Pearl Harbor’s “thereafter” meant being detained, dispossessed of property, and sent to incarceration camps.

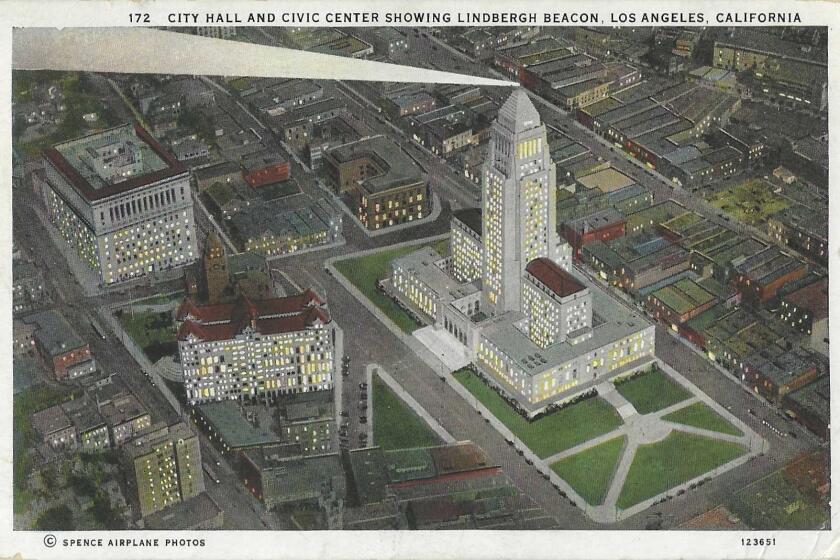

In 1941, about 36,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were living in and around Los Angeles, most of them within about five miles of Little Tokyo, the growing nucleus of the community for more than half a century.

They’d started arriving at the end of the 19th century, some of them brought to serve the railroads that the Chinese had helped to build. In 1882, the federal Chinese Exclusion Act had codified what California, by law and by violence, had been rolling toward for years.

The biggest railroad projects were finished, the gold mines played out (along with them, the state’s haul from the tax on foreign miners), and the Chinese appeared to the ever more populous white California like a menace, and the Chinese Exclusion Act capped years of intolerance and discrimination.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

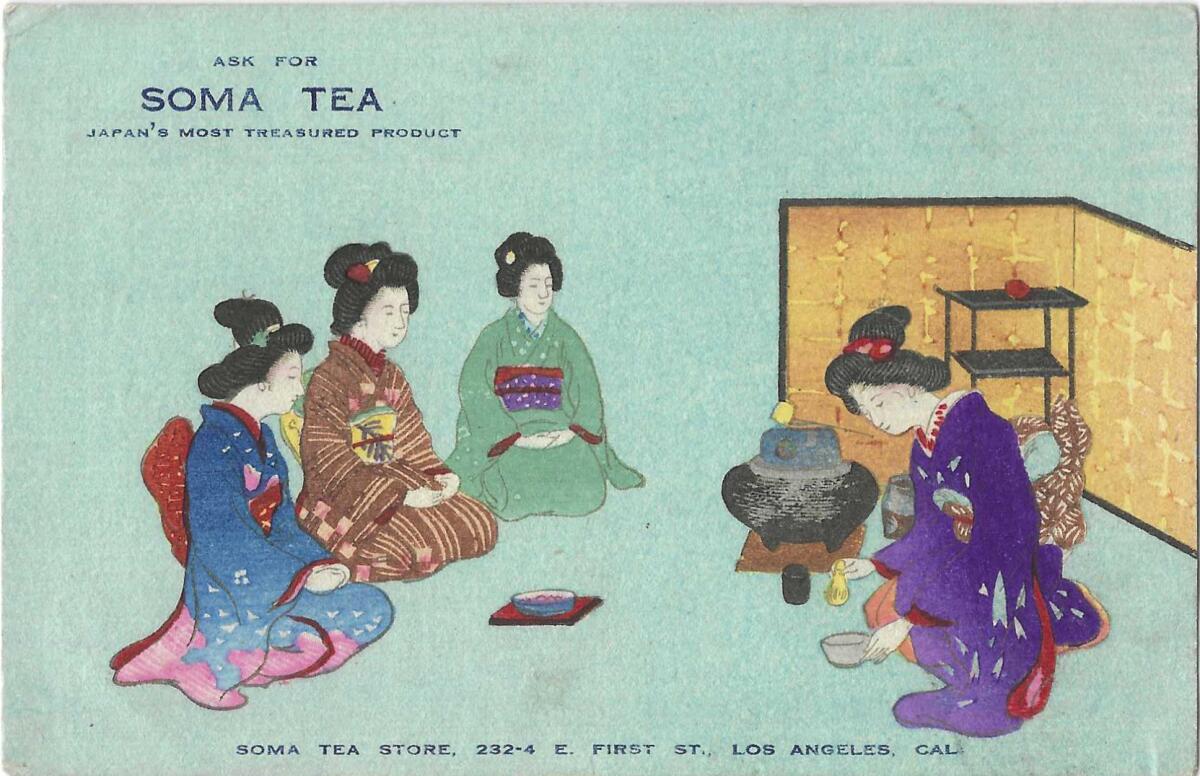

Still, California needed cheap labor, and some businesses sent recruiters to Japan. This new labor wave from Asia arrived legally, but ran up against some of the same kinds of proscriptions that the Chinese had faced, which is why Little Tokyo — like other cities’ “Japantowns” — formed and thrived: because of, as well as in spite of, the discrimination.

Sidelined from much of L.A.’s public and commercial life, these new residents — they weren’t allowed to become naturalized citizens until 1952 — began creating their own: schools, temples and churches, markets and restaurants. “They brought Japanese food and cultural traditions,” said Kristen Hayashi. She directs collections management and access at the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo.

“But they also adopted American traditions, so you see the emergence of Japanese American culture: baseball, even food traditions — you definitely see them incorporating some American foods.”

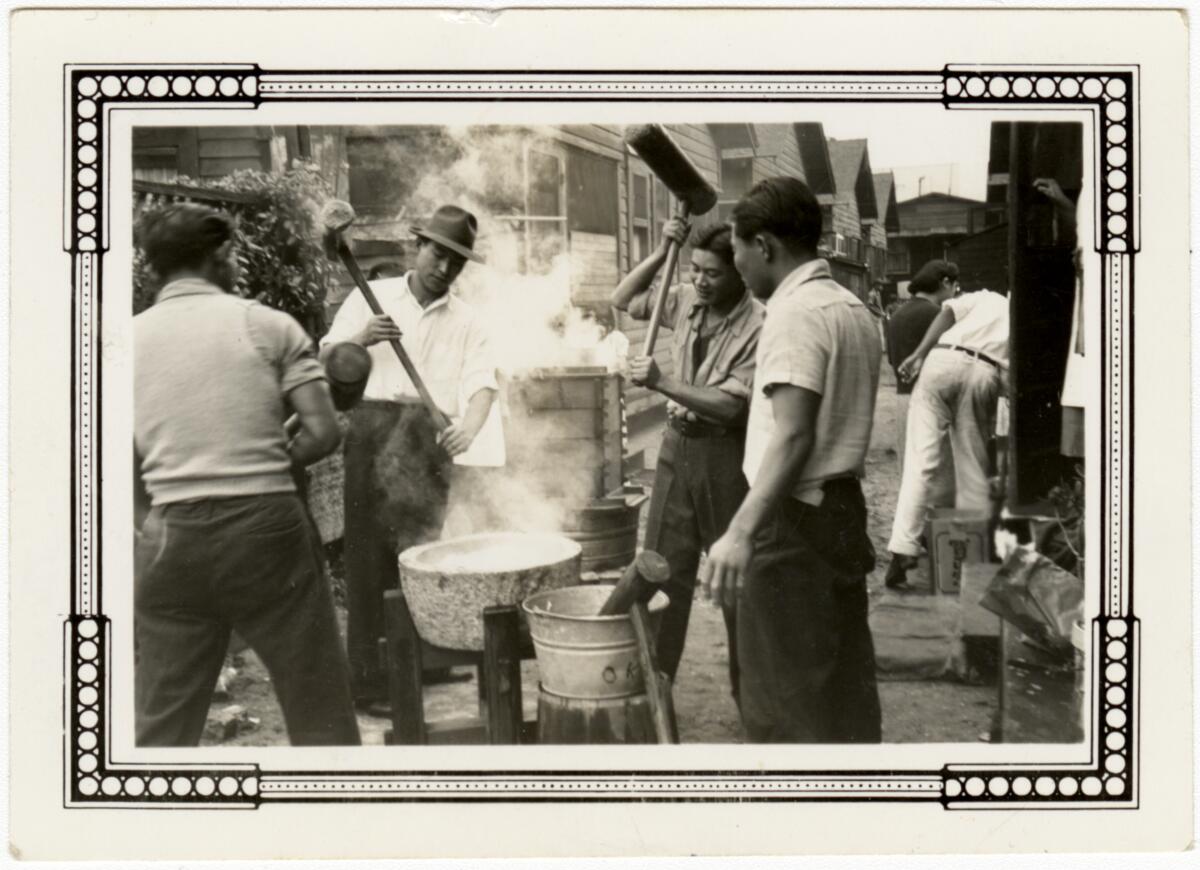

And vice versa. The traditional Japanese new year’s good-luck treat, mochi, has become a hugely popular fusion sweet in the U.S. It was the inspiration of civic leader Frances Hashimoto, born behind the barbed wire of a World War II-era camp. Working at her family’s Little Tokyo confectionary, she dreamed up a mochi ball with an ice cream heart, and if there’s a dessert hall of fame, this should be in it.

Little Tokyo is littler than it used to be. Part of it was sacrificed after the war to build the LAPD headquarters, Parker Center, which was itself razed a couple years ago.

Beyond the footprint of Little Tokyo itself, pre-war Japanese and Japanese Americans lived and worked across much of L.A.

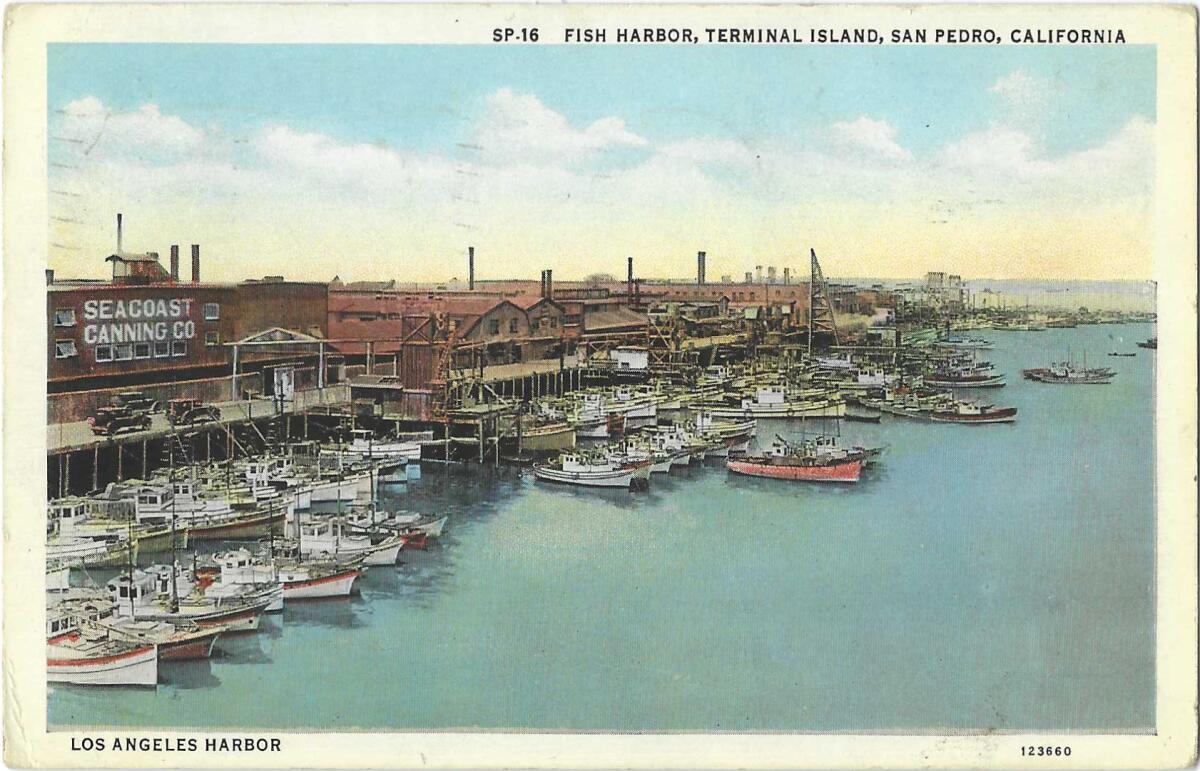

In Los Angeles Harbor, back when enormous tuna and sardine canneries there were packing up and shipping off Southern California’s sea harvest, a Japanese fishing village called Fish Harbor flourished from about 1906 on part of Terminal Island. Its fleet went to sea regularly and profitably; a Times headline from 1913 commented, “White men inferior to Japanese as fishermen.”

A 1994 Times story described the community with the main street called “Tuna Street.” The Baptist church sponsored children’s sumo tournaments, and the Buddhist temple organized the Boy Scout troop. The elementary school’s white teachers observed Japanese holidays. The Times, in 1926, described it amiably if condescendingly as “a bit of Japan translated to the shores of California.”

It was a company town, as Naomi Hirahara and Geraldine Knatz wrote in “Terminal Island: Lost Communities of Los Angeles Harbor,” but also, to some residents’ way of thinking, an “enchanted island.”

How that idyll ended, I’ll get to presently.

Looking around L.A. now, it does defy belief, but in 1949, and for many years before then (but never after), Los Angeles was the single most productive agricultural county in the nation. Much of that bounty — from celery to snapdragons — came from the sweeping square miles of what is now the thoroughly suburbanized South Bay and southeast L.A. County.

For the record:

5:18 p.m. Dec. 7, 2021A previous version of this article contained a photo caption from the Japanese American National Museum with an incorrect date. The image, showing a family in Torrance standing near two vehicles, was identified as being from about 1940. The image is from after World War II.

The Japanese — so often thwarted from owning land — leased many of the acres they worked there. Families with names like Muto, Sasaki and Ishibashi made crops grow and flowers bloom. Japanese farmers on the Palos Verdes Peninsula formed a cooperative “to compete with larger growers,” according to Judith Gerber’s book “Farming in Torrance and the South Bay,” which also pointed out that most never returned from being incarcerated during World War II, and that was evidently “part of the reason farming lost its economic importance in the region.”

The floricultural talents of Japanese gardeners were a status symbol — sometimes, as The Times wrote, on the assumption that the immigrant was made for the job, “in this case, the Japanese gardener, a humble servant whose mystical Eastern philosophy grants him a flair for plants and agriculture.” At one time, historians calculated, one Japanese American man in four was a gardener, and, as The Times noted, gardeners “became the cornerstone of the Japanese American community, establishing schools and churches.”

Like many communities of color, the Japanese population here perforce had its own doctors, lawyers, teachers, dentists and other professionals; white institutions often wouldn’t serve nonwhite clients and patients. In 1929, Japanese and Japanese American doctors tried to build a hospital in Boyle Heights to serve their own. The 1918 flu pandemic, when Japanese were turned away from some hospitals, was still warm in their memory.

The state of California insisted they couldn’t do it, but both the state and U.S. supreme courts sided with the doctors, and the Japanese Hospital opened, and flourished. It’s now a convalescent care operation. It is also a city historic-cultural monument. As its sign states, “Immigrant Japanese doctors prevailed in 1928 U.S. Supreme Court Case.”

It wasn’t just a hospital that got built. A new foundation of law and principle for Japanese people in California — and by extension the nation — was laid down too. When the hospital was being planned, a USC-trained lawyer named Sei Fujii — barred by his Japanese citizenship from the actual practice of law — with his law partner, Marion Wright, persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court in 1928 to let the Japanese doctors incorporate and build the Boyle Heights hospital.

But it wasn’t until the 1950s, after the war and after Fujii had spent years in a detention camp, that the California and U.S. supreme courts threw out California’s discriminatory 1920 law banning “aliens” from owning land, which by 1949 mostly had come to mean the Japanese. As the California court wrote, the real intent of the land law was “the elimination of competition by alien Japanese in farming California land.” Fujii, the subject of the 2020 biography “A Rebel’s Outcry,” was awarded his California law license posthumously, in 2017.

The 1913 ban on land ownership “was intentional,” said Hayashi, “to prevent social mobilization.” One work-around was buying or putting land in the name of U.S.-born citizen children.

And then, beginning Dec. 7, 1941, it was all swept away.

Fish Harbor went first. Even in the months beforehand, rumors were muttered that the quaint village of the 1920s and 1930s was a spy colony. As The Times described the suspicions, in 1994, the poles for drying fish were suddenly cast as “antennas.” Navigational charts became, in the public’s imagination, coastal maps. Japanese fisherman, fit and strong from their trade, were being trained by the Japanese military, and their boats were ready to do double duty as torpedoes. After the war, the U.S. government acknowledged no instances of spying or sabotage emerged from Fish Harbor.

Beginning within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, the FBI arrived to start taking away the village’s leaders. Two months later, Japanese-born residents with a fishing license were also taken away. A few weeks later, the other residents of Fish Harbor, U.S. citizens among them, were given 48 hours to evacuate, and most were sent to incarceration camps. The village was bulldozed, possessions vanished. And, like the farmers of the South Bay, the fisherfolk of Fish Harbor did not return.

Unusually, some Japanese gardeners resumed their old trade after the war, perhaps in part because hostility kept them from getting hired to do anything else. In 1955, they created the large and thriving Southern California Gardeners’ Federation. Members could shop for supplies at a Little Tokyo co-op, which closed in 2012.

One remarkable survivor was Tokio Florist, another L.A. city historic-cultural landmark. Hayashi told me that it was founded and operated for two generations by women who grew on their property many of the flowers they sold. I used to stop there almost once a week to buy their unusual and remarkable blooms. The Sakai family was sent to Manzanar during the war. Someone evidently looked after the property for them, and in 1960, the family moved the business to Silver Lake. They closed the place in 2006.

Another piece of surviving Japanese landscape artistry is the Storrier Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena, open to the public on certain days of the week. It was designed and built between 1935 and 1941 — there’s that date again — by landscape designer Kinzuchi Fujii, and it has earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. Fujii was sent to a relocation camp, and there are accounts that in the single suitcase he was allowed to take with him, he carried plans and photos for the garden that he never saw again.

And before they too were evacuated to incarceration camps, the staffers of the Rafu Shimpo, L.A.’s Japanese-language newspaper, founded in 1903, managed not only to arrange to keep up the rent on the paper’s Little Tokyo offices, but to hide the Japanese-language lead type under the office floorboards, and so start publishing the paper once again, on New Year’s Day 1946.

“While Pearl Harbor upended Japanese American lives, it’s part of a long arc of discrimination,” Hayashi told me. “You had these FBI surveillance lists of Japanese immigrants long before Pearl Harbor. It could be for benign things like they were a Japanese language teacher, or sent money to a charity in Japan, or if the Japanese navy visited the U.S., they would socialize. They were seen as being suspicious. There was never any reported case of espionage … these were just false charges that were made by the FBI’s surveillance.”

In time, the restrictive covenants and laws that isolated Japanese and Japanese Americans were thrown out. The concentrated population once clustered around Little Tokyo — if it came back here from the camps — moved farther afield. Then, in 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, issuing reparations and an apology to the 100,000 or so whose lives were among the many thousands more that were broken, some beyond recovery, on Dec. 7, 1941.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.