From the Archives: Victorville’s fallout shelter

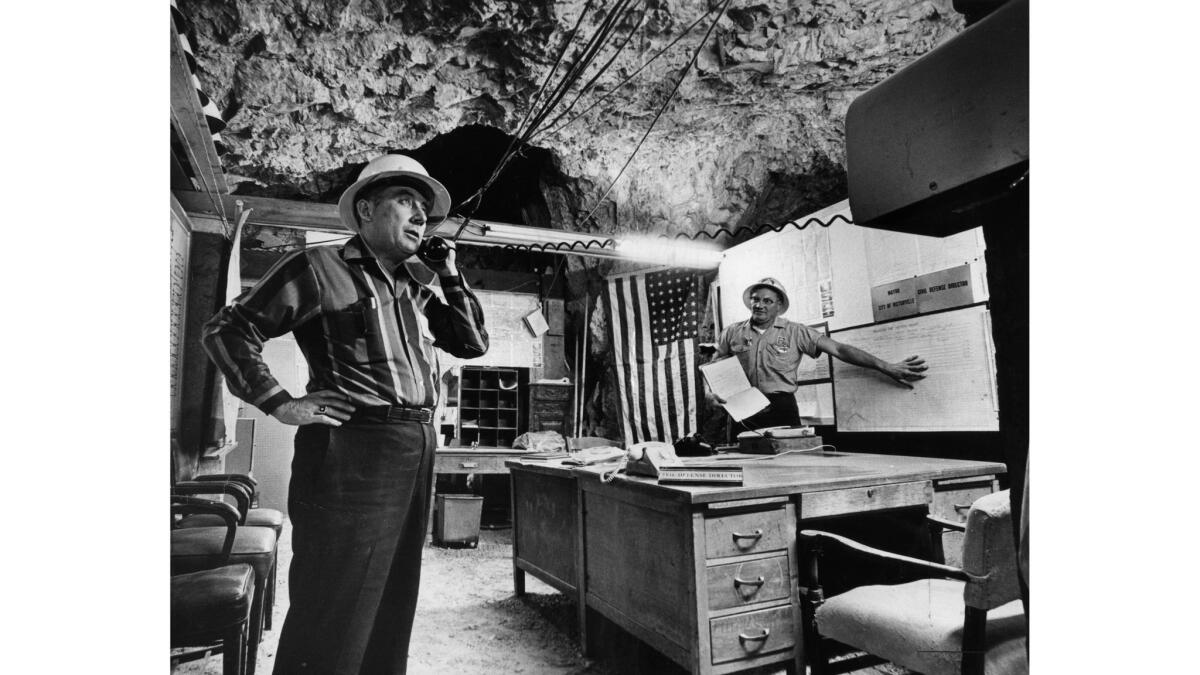

William C. Melton, left, the city of Victorville’s civil defense coordination, takes a phone call as his top aide, Phil Mull, looks on, in the fallout shelter command post located 185 feet below surface level.

In a May 26, 1968, article, Charles Hillinger began:

The fallout shelter program, forgotten practically everywhere in America, is alive and well in Victorville.

The Mojave Desert town of 10,000 people, 100 miles northeast of Los Angeles, is still red hot on civil defense.

“One of the saddest things in the United States today,” says William C. Melton, Victorville’s civil defense coordinator, “is the extreme apathy about the bomb.”

“People don’t seem to worry much about the atomic age, or realize that the Russians are capable of delivering nuclear weapons without warning within 15 minutes.

“Or that China has two nuclear subs and will have two more this summer, subs that might even now be off our shores ready to destroy our cities.”

Melton, 49, owner of a local hardware store, made his observations as he manned his command post 185 feet below the surface in a 510-foot-deep mine shaft.

His top aide is gas station mechanic Phil Mull.

The command post is furnished by desks, chairs, an American flag, organizational charts, maps of every state, filed, telephones and radio transmitters.

For months, more than 300 Victorville residents have taken turns underground digging out one of the world’s most unusual fallout shelters.

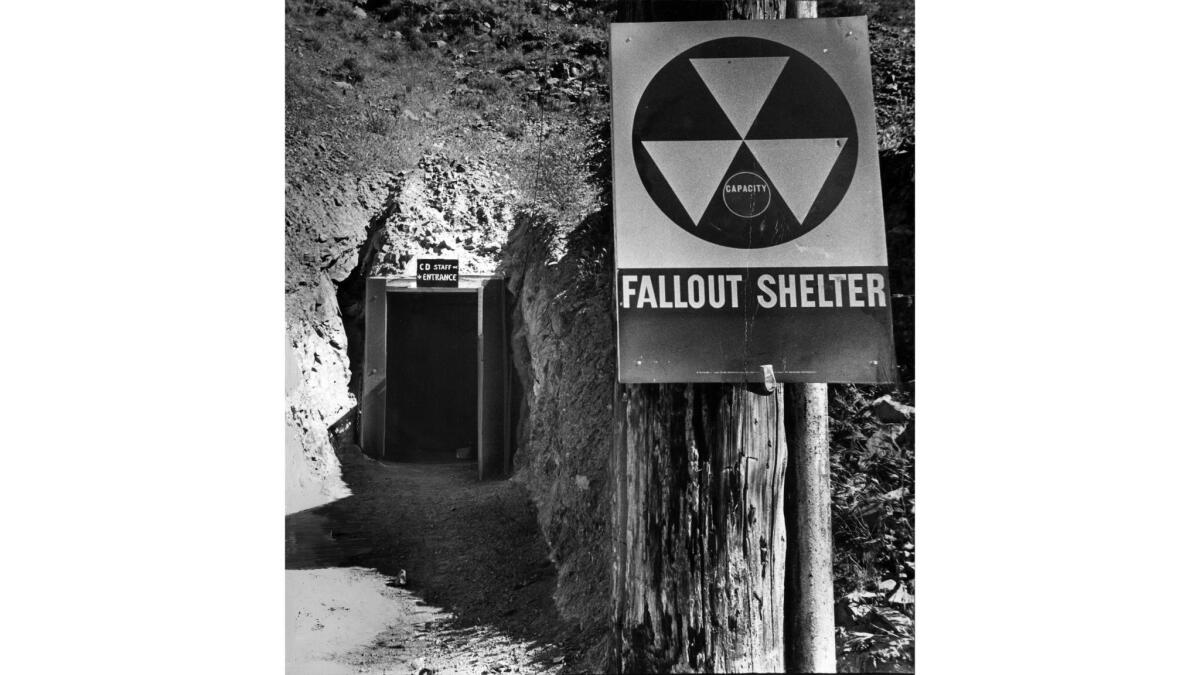

It is located in the abandoned Sidewinder Gold Mine, whose entrance is 4,200 feet up the west face of mile-high Sidewinder Mountain. It it 17 miles northeast of Victorville, but only seven miles from Carefree Acres.

Townspeople have stocked 1,095 feet of abandoned shafts with enough water, food, uncontaminated clothing, sanitation, medical and other supplies to take care of 1,100 men, women and children for three weeks.

“And all it’s cost the taxpayers of Victorville so far is $369,” said Melton.

Service club fund-raising drives and individual contributions have taken care of other costs, Melton said. …

Melton, Hull and others in Victorville dedicate 15 to 20 hours a week working on the shelter, getting ready for the day the bomb is dropped.

Within five years, apathy won. A May, 7, 1973, Los Angeles Times article reported that ,” while not officially abandoned, the shelter lies vandalized, looted and largely forgotten.”

Also, Melton’s position as the Victorville civil defense director had been abolished.

See more from the Los Angeles Times archives here