How many high school students will come back in the fall? Dismal return rate raises alarms

Only 7% of high school students and 12% of middle school students have returned to reopened campuses in the Los Angeles school district, sounding alarms about what these figures portend for next fall and highlighting the need for intense intervention when more traditional in-person schooling resumes.

As the school year winds down with the vast majority of students at home online, an uncertain summer and fall back-to-school future is emerging: How soon will families be ready to return children to campus? Will many demand an online option? Will students attend summer school to stem learning loss?

For state Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell (D-Long Beach), the return data denote a crisis.

“It’s tragic for the future of those students and tragic for the future of California,” said O’Donnell, who chairs the Assembly Education Committee. “It means students are not receiving in-classroom instruction — where they learn best. What does this mean for the fall?”

Although officials insist they will act aggressively to help students, the low return rate could intensify pressure on the school district.

COVID fears and restrictive part-time campus schedules contribute to the low numbers. Officials hope those students who need the most help are returning.

Even after L.A. Unified instituted some of the most extensive safety measures in the nation, it was not enough for many families still fearful of the pandemic. Others, especially high school students, rejected the strict limitations on movement, instruction, enrichment activities and socializing and opted to stay with distance learning. For many, the gradual reopenings from mid- to late April were too little, too late — and families chose not to disrupt schedules and obligations so late in the school year, which ends June 11.

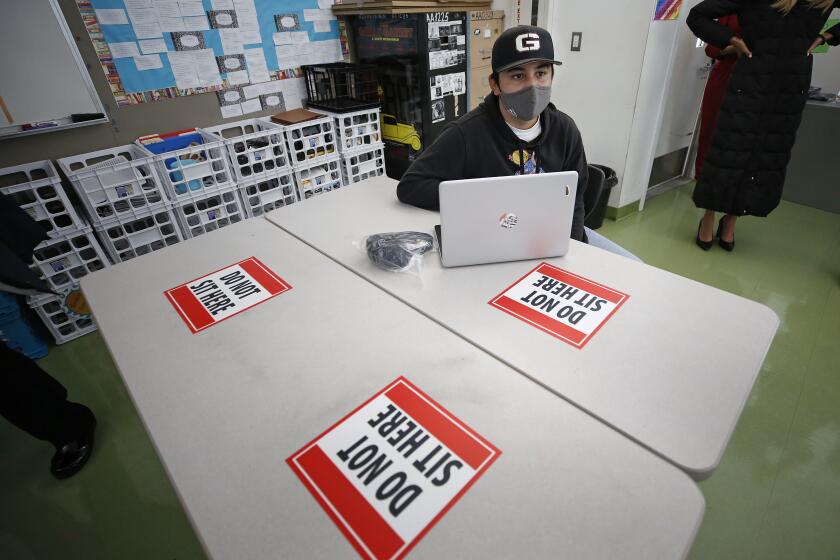

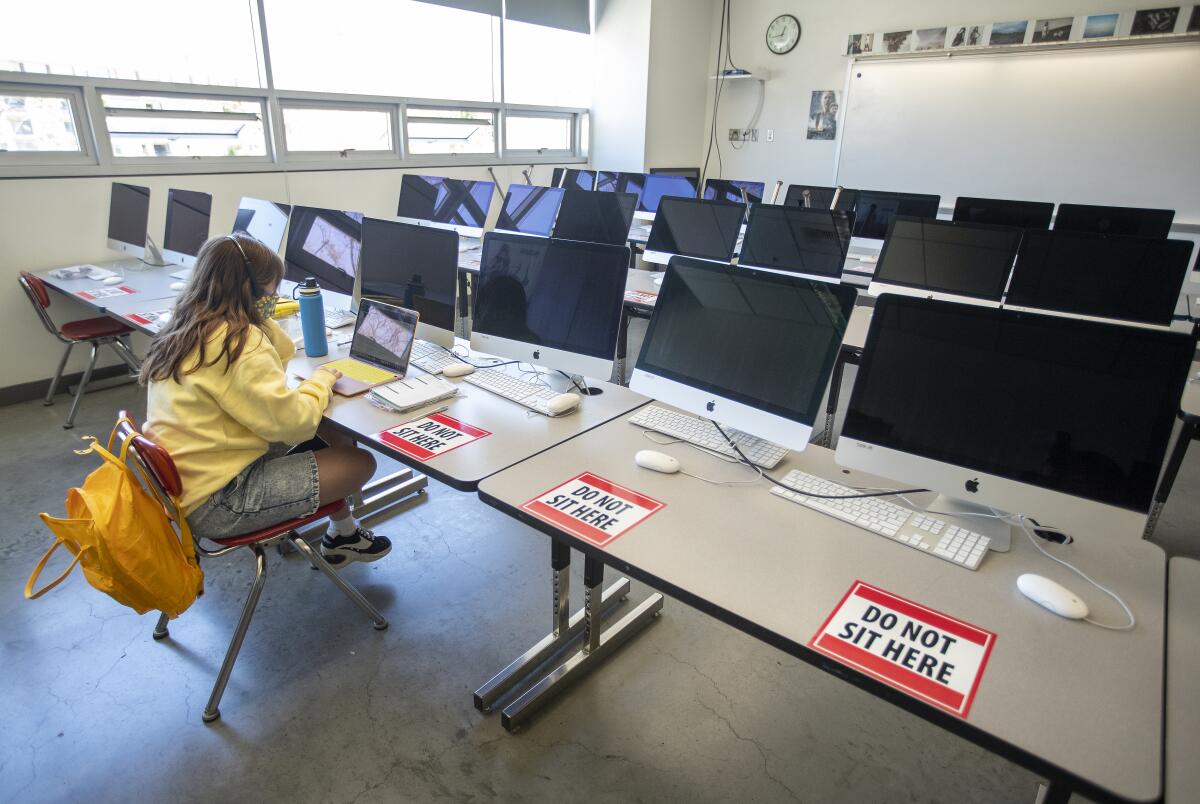

The L.A. Unified reopening plan offers both middle and high school students a half-time, on-campus academic schedule that includes no in-person instruction. Instead, students must remain in one classroom, from which they log into their classes. The teacher in the room is instructing other students online in various places. Twice a day for 30 minutes, that teacher will engage directly with the students in the room for an activity to support their social and emotional needs.

The district adopted this approach to limit the mixing of students as they move from class to class, something that many other districts have allowed.

This format was a miscalculation, said Tressa Pankovits, associate director for Reinventing America’s Schools at Progressive Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C., think tank.

“If a kid is miserable doing Zoom lessons, why force them to do it in an unfamiliar classroom with a teacher whose attention is on students in another class? It’s a ridiculous proposition, really,” Pankovits said. “It’s inarguable that LAUSD tried too hard to balance the demands from the adults, clearly at the expense of its students.”

Others have defended the safety-first format.

The ‘Zoom in a room’ option for in-person schooling — the format for high schools in Los Angeles and San Francisco — has failed to draw back the vast majority of students.

Board of Education members must now enact a plan to spend billions of dollars in one-time state and federal aid just as they launch a search for a new district chief, after Supt. Austin Beutner announced last month that he was stepping down at the conclusion of his three-year contract at the end of June.

Board member Nick Melvoin acknowledged that the limited secondary format means “fewer students are choosing to return.” He added: “This underscores the need for a full-time, in-person learning option that looks as close to normal as possible for the fall.”

Board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin doesn’t think the short-term, unpopular format will drive families away, but “I am still worried about the steady enrollment decline generally and look forward to robust decision-making about how to use our once-in-a-lifetime funding for once-in-a-lifetime opportunities for our students and our schools.”

School board member Jackie Goldberg said her concerns will amplify if students do not return in large numbers to summer school, which will provide in-person instruction at all grade levels, she said.

Teachers also will need to return for summer school to accommodate large numbers of students. But having money to pay them does not automatically mean the district will be able to hire enough additional teachers, tutors, counselors and nurses to boost academic and psychological recovery.

Board member Monica Garcia noted the trauma suffered by many families and stressed the importance of offering options to families — positions that are widely held.

O’Donnell said the Legislature is extremely unlikely to allow any school system to remain entirely online in the fall, but could work out provisions that would allow individual families to make that choice. He added that it would be important for online offerings to be more robust than the independent study options of the past — another point of broad agreement.

The number of returning students at all grade levels has been lower than expected based on earlier parent back-to-campus surveys: About 30% of elementary school children have returned and 12% of middle school students. And despite low expectations for secondary schools from the onset, the district had anticipated more than twice as many would return.

About 8,000 high school students have returned, while more than 105,000 have not. These numbers do not speak to whether students are attending classes online or are academically engaged.

The vast majority of the district’s 465,000 students have not had in-person classes on campus since March 13, 2020. Although Los Angeles attendance is particularly low, many of California’s largest school districts are struggling to persuade high school students to return. The majority of the state’s secondary school students will end their year much like it began — fully online.

Beutner said vaccinations will be crucial for getting students back on campus, and called Monday for a school-based student vaccination campaign to begin before the end of the current school year. On Wednesday, federal authorities are expected to approve vaccination guidelines for the Pfizer COVID-19 shot for anyone 12 and older under an emergency-use authorization.

“We actually think vaccination is the path to return students to school as soon as possible, as safely as possible,” Beutner said. “One of the answers to helping underserved communities is to bring the vaccine to school. Our goal is to provide the opportunity for every 12- to 18-year-old to be vaccinated well in advance of school starting in August. And well in advance means now, not July 15 — trying to find children who aren’t at school.”

The district has joined with private and public health partners to open vaccination clinics at 13 schools, where no appointment is required, and is ready to expand further. If other government agencies commit to providing the doses, Beutner said, the district will manage the remaining logistics: “There is no time to waste in that effort.”

Wider vaccine distribution would make school communities safer and could build public confidence, he added.

Beutner also said that he sees an important silver lining in the numbers. He noted that a higher percentage of high school students have returned to campus in lower-income communities, including those that suffered most during the height of the pandemic. Teachers, counselors and principals, he said, are reporting that “those who most need support are there.”

As evidence, he noted that 12% of high school students who live in the Huntington Park/Vernon area, with a median income of $44,231, have returned to campus compared with 4.8% in West L.A., with a median income of $116,083.

“These may be students experiencing homelessness, those who are part of the foster care system, students who don’t have adequate Wi-Fi at home, students who need a safe and secure place to study,” he said. “Those are the students who are back, and we’re able to support them.”

Beutner has a point, “although there are certainly more than 7% of students who could really use help,” said Wendy Murawski, executive director of the Center for Teaching and Learning at Cal State Northridge.

The district has yet to release numbers on what percentage of students in each of these high-need categories is returning. About 80% of L.A. Unified students come from low-income families; 20% are learning English, and about 13% have disabilities.

“I think we have a lot of students who have checked out,” Murawski said. “They’re not getting their needs met and so they’re going to stay home and call this year a wash. Others have managed it — have figured out a way to handle it.”

Although there’s been learning loss, there’s also been burnout, added Murawski, who has a child in high school who decided not to return. For many students, it’s about just getting through the next five weeks, saying, “‘I just need to be done. I’m not gonna go back to school. I’m not gonna try anything new.’ I’m really hoping that that changes for next year.”

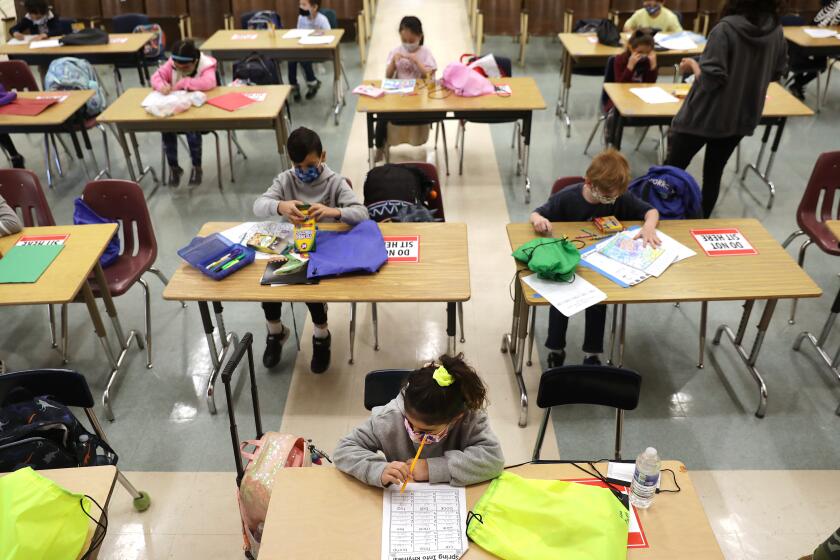

In-person schooling looks very different from neighborhood to neighborhood, especially at the elementary school level.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.