Only 7% of LAUSD high school students return to reopened campuses, far less than expected

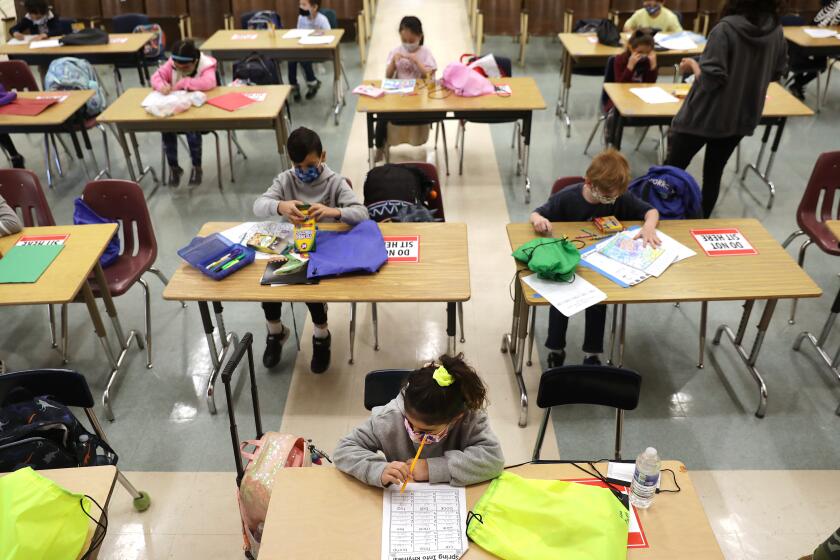

Only 7% of high school students have returned to campuses in the Los Angeles Unified School District, where extensive safety measures have failed to lure back the vast majority of families in the final weeks of school for myriad reasons in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, attendance numbers at all grade levels in the nation’s second-largest school district have been lower than expected based on earlier parent back-to-campus surveys: About 30% of elementary school children have returned and 12% of middle school students. And despite low expectations for secondary schools from the onset, the district had anticipated that more than twice as many middle and high school students would return.

The vast majority of the district’s 465,000 students have not had in-person classes on campus since March 13, 2020 — most of that time because of pandemic-forced school closures, but more recently by choice.

Although Los Angeles attendance is particularly low, many of California’s largest school districts are struggling to persuade high school students to return to campuses amid coronavirus safety restrictions that limit interactions with friends, restrict movement and offer part-time schedules. The majority of the state’s secondary school students will end their year much like it began — fully online.

To bring students back to campus in large numbers by the fall, L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner on Monday called for a school-based student vaccination campaign to begin before the end of the current school year.

Although LAUSD campuses appear to be operating safely and coronavirus positivity rates in Los Angeles have tumbled — allowing for widespread openings — parents have expressed various reasons for keeping children home.

Many in communities hard-hit during the winter surge are not sufficiently reassured that schools are safe. Others have told The Times they were put off by safety practices they consider unnecessarily extreme, especially in middle and high schools. And some parents and students said they were hesitant or unable to disrupt ongoing routines so late in the school year, which ends June 11. Elementary schools began reopening in the week of April 12; middle and high schools the week of April 26.

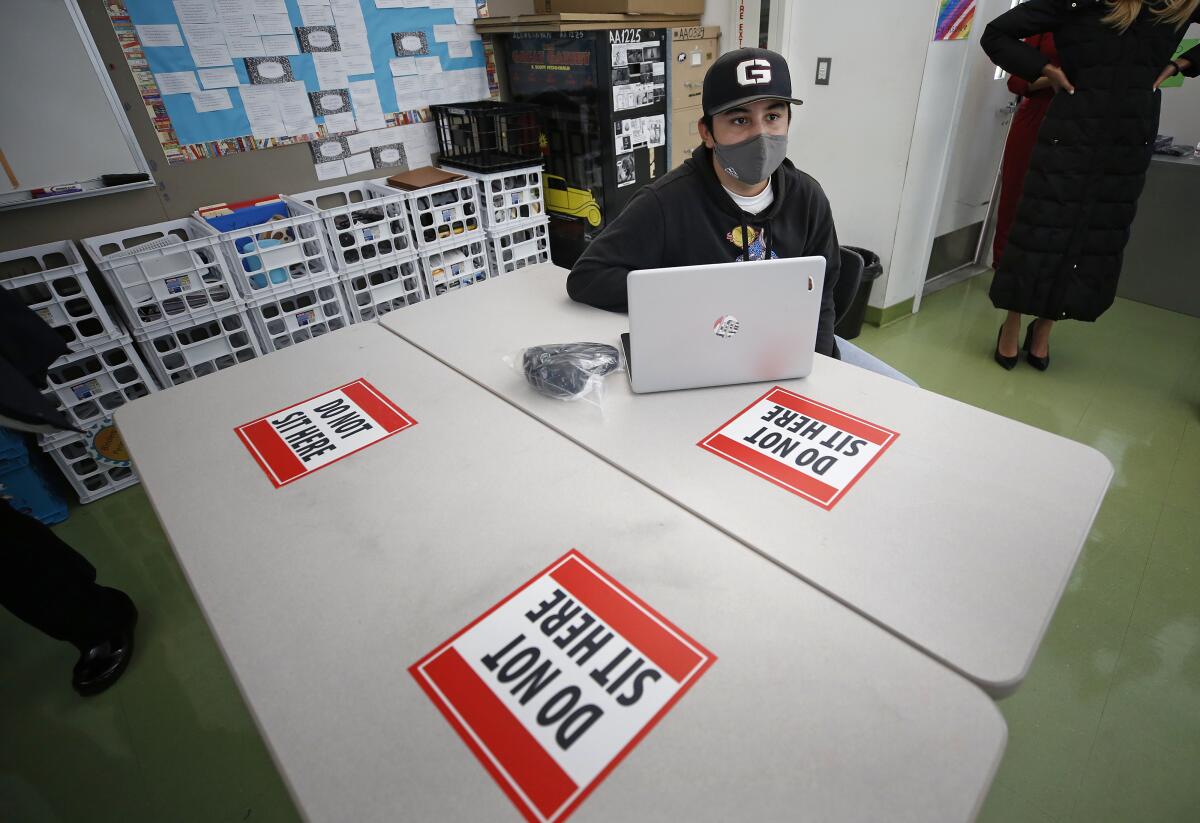

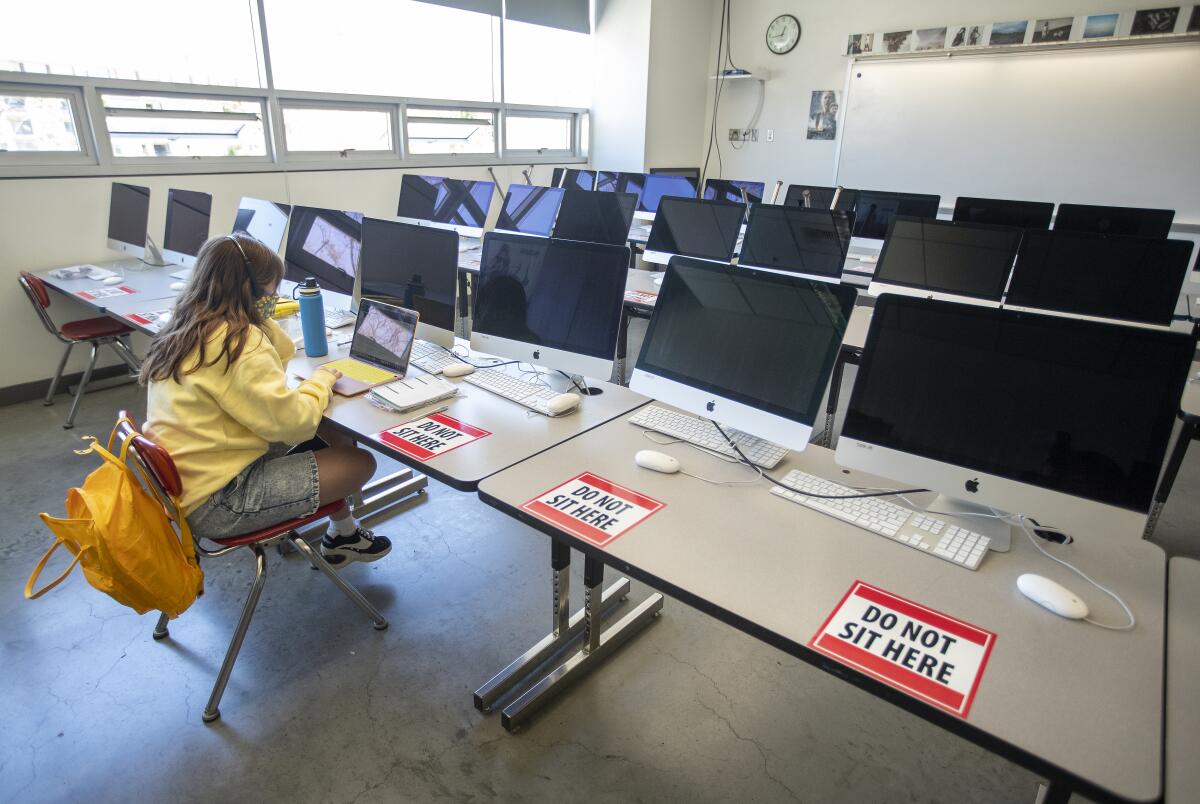

The ‘Zoom in a room’ option for in-person schooling — the format for high schools in Los Angeles and San Francisco — has failed to draw back the vast majority of students.

The rate of high school return is a disappointment to officials, who developed a format that allows students back on campus but keeps them in one classroom all day, doing the same online learning they were doing from home.

These low on-campus numbers do not mean that students are failing to attend classes — they’re still expected to log in from home.

Beutner said in an interview that he sees an important silver lining in the numbers. He noted that more high school students have returned to campus in lower-income communities, including those that suffered most during the height of the pandemic. Teachers, counselors and principals, he said, are reporting that “those who most need support are there.”

As evidence, he noted, that 12% of high school students who live in the Huntington Park/Vernon area, with a median income of $44,231, have returned to campus compared with 4.8% in West L.A., with a median income of $116,083.

“So there’s two ways to look at the high school number,” Beutner said. “One can look at it and say, Gosh, we need more students back. Absolutely we do.” All the same, he said, the students “most in need” are returning. “These may be students experiencing homelessness, those who are part of the foster-care system, students who don’t have adequate Wi-Fi at home, students who need a safe and secure place to study,” he said. “Those are the students who are back, and we’re able to support them.”

The district has yet to release numbers on what percentage of students in each of these high-need categories is returning.

About 80% of L.A. Unified students come from low-income families; 20% are learning English; about 13% have disabilities.

The district calculated return rates based on where students live, with the district divided into 44 “communities of schools.” Although, as Beutner noted, there’s a strong correlation between lower-income areas and higher return rates, the figures for high school students are low everywhere.

Among the higher rates of return, five of the 44 school communities have 10% or more of their high school students back in person. At the other end, four communities have a return rate of less than 5%.

In-person schooling looks very different from neighborhood to neighborhood, especially at the elementary school level.

There’s no clear pattern for middle school students. And among elementary schools, more prosperous communities are returning in much higher numbers, topped by West L.A., where just over two-thirds of students have returned, compared with Bell/Cudahy/Maywood, where less than 20% have returned.

Beutner said the picture at elementary schools trends differently because the program available for students is robust enough to attract most families who generally don’t have persisting safety concerns. This includes areas such as West L.A., where COVID-19 caused comparatively less illness and death.

For elementary grades, the district is offering a half-day of in-person instruction on campus Monday through Friday, with additional supervision available to cover from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Beutner acknowledged that middle and high school students have had less to look forward to.

While middle school students also have the benefit of daily supervision from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., both middle and high school students have a half-time on-campus academic schedule that includes no in-person instruction.

Students must remain in one classroom, from where they log into their classes. The teacher in the room is instructing online to students in various places. Twice a day for 30 minutes, that teacher will engage directly with the students in the room for an activity to support their social and emotional needs.

“The model that they’ve come back with is really lacking a focus on instruction, having kids return back to school to only do Zoom in class and not have real instruction isn’t creating learning,” said Vanessa Aramayo, head of Alliance for a Better Community, a local advocacy and social services nonprofit.

The district adopted this approach to limit the mixing of students as they move from class to class, something that many other districts have allowed.

The next necessary confidence-building measure is vaccines for students who are 12 and older, said Beutner, who wants to expand ongoing school-based community vaccination efforts.

Health authorities could give the Pfizer vaccine an emergency-use authorization for children as young as 12 as soon as this week.

“We actually think vaccination is the path to return students to school as soon as possible, as safely as possible,” Beutner said. “One of the answers to helping underserved communities is to bring the vaccine to school. Our goal is to provide the opportunity for every 12- to 18-year-old to be vaccinated well in advance of school starting in August. And well in advance means now, not July 15 — trying to find children who aren’t at school.”

If other government agencies commit to providing the doses, the district will manage the other logistics: “There is no time to waste in that effort.”

In the interview, Beutner also addressed complaints that arose last week after he announced the reopening of elementary school playground structures. Parents at some schools reported that their playgrounds had not reopened or that their children would have access for only about 30 minutes every two to four weeks.

“The direction I’ve given is to reopen playgrounds carefully, making sure that you can follow the appropriate set of protocols and practices,” Beutner said.

These rules allow only one class on play structures at a time and call for sanitizing between groups. The number of classes and available staff to supervise and clean could be limiting factors, Beutner said.

“I was at a school myself: The slides were open, but the monkey bars weren’t yet. We’ll get there. It’s not one size fits all. We have almost 500 elementary schools. We’ll see more reopenings as the weeks progress. Unlimited access, which might have been possible pre-COVID, may be less possible.”

Although city and county parks don’t have similar restrictions, county health Director Barbara Ferrer was generally supportive last week of the district’s playground safety protocols.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.