California high schoolers are saying no thanks to reopened campuses and are staying home

During the first week of in-person learning at Panorama High School, drama teacher Patricia Francisco stood in the mini-theater talking on Zoom to her acting class. Two stage lights brightened her face as she spoke to her camera. Students were logging in from home, or from classrooms scattered around campus. Most appeared as black boxes on her screen.

“You guys who are on campus — I’m so proud of you for being here,” she said. “Those of you who are at home — we can succeed in any environment that we are ending up in.”

Except for her voice, the room was silent. Only three students were physically in the class — and they weren’t paying attention to her as they attended other online classes while wearing noise-canceling headphones. Returning to school in Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, means sitting in one classroom all day, two or three days a week, with little intermingling or movement.

This “Zoom in a room” option for in-person schooling — the format for high school in Los Angeles and San Francisco — has failed to draw back the vast majority of students. Although official attendance data have not yet been released, a survey of L.A. Unified parents indicated that about 17% of high school students would come back to campus.

L.A. Unified is hardly alone in struggling to persuade high school students to return — or in offering a lean reopening experience.

A few large districts, including Santa Ana Unified and San Bernardino Unified, have not broadly reopened campuses, including for high school students. But most of California’s largest districts are providing a patchwork of reopening approaches based on how local school boards weighed risks and benefits and how they met demands from teacher unions over back-to-campus working conditions. One big district, Corona-Norco Unified, has more than 75% of its students back. In others, it’s closer to 20% with more limited schedules.

The Times’ All-Star football team includes players of the year Matayo Uiagalelei, back of the year Zevi Eckhaus and lineman of the year Andrew Madrigal.

Despite detailed planning, the majority of secondary school students in California’s largest districts will end their year much like it began — fully online, according to state data. For many, it will mean 17 or 18 months away from classrooms.

Statewide, about 84% of secondary school students have the option to return to their middle and high schools in some form, according to state data, which do not separate out high schools. An estimated 48% of all secondary students at schools that are open have returned to campus.

Reopening elementary schools was simpler: one class, one schedule. But educators have grappled with complex secondary schedules in which students move from classroom to classroom. The goal of safely bringing them back to campus has largely resulted in limited schedules and restrictions on hallway encounters, lunch with friends and extracurriculars, among other rules.

A Times review of many of the state’s largest school districts revealed a range of approaches to reopening high schools:

- In Elk Grove, the largest district in Northern California, students who opted for in-person instruction are allowed to come to campus four days a week or twice weekly, for five hours per day. They move from class to class, with teachers simultaneously instructing in-person and online students. About 22% of students opted to return — a little over half chose the two-day schedule.

- In Fresno, students can attend classes two days a week for four hours of in-person instruction. About 49% returned to campus, the rest remain online.

- In San Diego Unified, the state’s second-largest district, students can be on campus two to four days a week — depending on space — and move from class to class for up to three periods per day. About 40% of high school students have returned.

- In Corona-Norco, where three in four students are on campus, students chose at the start of the school year whether they would return in person when campuses reopened and were assigned to online or in-person teachers based on that. Changing the decision meant getting a new teacher.

With only weeks left in the academic year, the reopenings have put new pressure on students and teachers.

“No matter what situation you’re in, you’re having to relearn how to learn information and engage content,” said A.Dee Williams, professor of education at Cal State Los Angeles. “In high school, you have maybe six different subject matters that you’re having to re-engage in a way you never have before.”

Three large Southern California school districts — Long Beach, Los Angeles and Capistrano Unified — reflect the various scenarios playing out across the state.

Los Angeles Unified: Zoom in a room

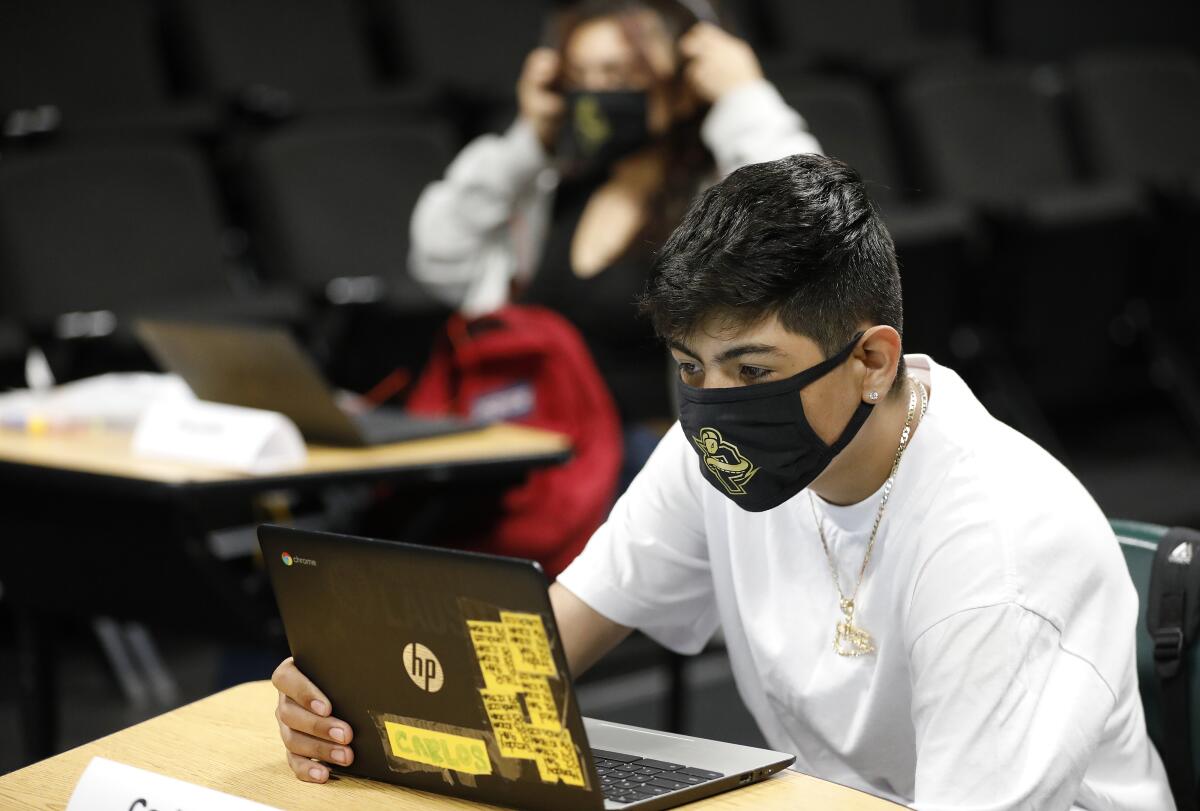

Ninth-grader Carlos “Jairo” Zamora, 16, looked a little sleepy-eyed, but he lit up when asked how he felt during the first week back at Panorama High School, where he was one of three students in Francisco’s drama class.

“I wanted to interact with other people,” he said. “I really did miss school. And I wanted to learn more.”

It didn’t bother him that the teacher in front of him was instructing students elsewhere.

“She does her thing,” he said, “we do our thing.”

In L.A. Unified, middle and high school students are on campus for a full day in a schedule that alternates two-day weeks with three-day weeks. Students report to an assigned room and log into online learning just as they would have at home. Officials said keeping students together reduces the opportunity for the coronavirus to spread.

Francisco has faced unique challenges with her drama students at Panorama. Unlike at home, those on campus can’t stand up and deliver a monologue or do a movement exercise while in their assigned classroom. Instead, they do quiet work while on campus — reading, writing a script or designing a set.

Overall, the parents of about one in five students at Panorama indicated they would return to campus. More than 90% of the school’s students are Latino, and 96% are from low-income families.

The few who have returned are trying to make the best of it.

For Emma Espinoza, a junior at Lincoln High School in Lincoln Heights, the decision came down to softball.

“If I didn’t play sports, I’d probably stay home too,” the 16-year-old said. Her team practices just about every day, and catching the bus to a game is easier from campus, she said. She didn’t see the point of sitting in a room all day on Zoom, but “I adapt very easily.”

Long Beach Unified: Moving from class to class

Long Beach Unified, the state’s fourth-largest school district, was the first big district in L.A. county to widely reopen, largely because the city has its own health department and vaccinatedd teachers earlier than other districts.

High school students, who began returning in late April, are split into cohorts that attend classes together two or three days a week. Students can move from class to class.

Yet most students remain online only. About 37% have returned, ranging from about 25% to 46% at the district’s the 11 high schools.

At Millikan High School in East Long Beach, teacher Andrea Glenn was joined by five of 32 students in her “Justice in America” class. The others participated on Zoom. She positioned two laptops in the room to ensure constant visibility with students. After taking attendance, she began juggling between online and in-person students.

Greeting the in-person students, Glenn explained measures designed to keep them safe, including four fans and an air purifier. If she was going to remove her mask to sip water, she would do so in a corner. And she would do her best to keep her distance.

As she spoke, online students occasionally chimed in on speakers, asking for help.

Principal Alejandro Vega said the demographics of those staying home reflect the region. “Asian, Black and Latino students are staying home at higher rates,” he said.

Like many high school teachers, Glenn said her online students tend to keep their cameras off and microphones muted. Sometimes it’s because they don’t have the best internet access. Sometimes they’re baby-sitting. About 36% of the school’s students are from low-income families, 45% are Latino and 30% are white.

Simultaneously teaching online and in person “is exhausting,” Glenn said.

But, she added, “a couple of them were giggling about something and it made me so happy just to hear students laughing. I missed that noise.”

Capistrano Unified: An October opening

High schools in Capistrano Unified School District in South Orange County are outliers among large districts, with campuses open since October. When Orange County COVID-19 rates dipped in the fall, several county districts, including Capistrano, seized the opportunity.

High school students could return for a full day — and move from class to class — but only for two days a week because of capacity limitations driven by a requirement to keep six feet of distance between students. Many classrooms were nearly empty, and many students returned to online learning as the months passed, officials said.

In April, after the district lowered the distance requirement to three feet, it began allowing students on campus for a full day, four days a week. Now, about 42% of high schoolers are on campus. Increasing on-campus attendance became an imperative given students’ online struggles, leading to a rise in Ds and Fs.

“These are students who have been successful but are struggling,” said Meredith Hosseini, assistant principal at Capistrano Valley High School in Mission Viejo, where about 30% of students are from low-income families and about half are white.

She said school administrators and teachers are finding creative ways to persuade students to return by restoring the hallmarks of the high school experience — “in a modified way.” The school’s sprawling campus has helped by allowing activities to take place outside.

The school held a football game with a homecoming court in April, an annual air guitar concert and a performance of “Urinetown: The Musical” for which the school built an outdoor stage behind the theater.

“We’re trying to get to the point where you have to do less squinting to make it feel like a real school,” said Principal John Misustin.

On the first day of the four-day-a-week model, the school’s choir director, Erin Girard, sat at a grand piano on the theater stage. The faces of about 10 students online could be seen quietly watching from a laptop on the piano. The 23 in-person students, who were together in one room for the first time, were preparing a show and seemed jubilant to be singing and dancing with one another.

“It’s not just good for our vocals, it’s good for our souls,” Girard said.

Times staff writers Laura Newberry, Melissa Gomez and Iris Lee contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.