China’s population and economy are a double whammy for the world

China’s ‘one-child’ policy has slowed population growth and brought prosperity — but it couldn’t avert massive damage to the environment.

An escalator in the Beijing subway is jammed with people. China’s experience shows how rising consumption and even modest rates of population growth magnify each other’s impact on the planet. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

July 22, 2012

Fourth of five parts

XIAMEN, China — A 6-year-old girl with a bob haircut sat alone on an enormous wraparound couch, dwarfed by the living room furniture and a giant flat-screen TV.

As she flicked the remote in search of cartoons, her parents pointed proudly to the recessed lighting and high ceilings. Then they proceeded with an official tour of their three-story house with white marble floors, oversized windows and a granite entryway flanked by a Corinthian column.

All of this was paid for with a $100,000 interest-free loan from the Chinese government, an incentive to keep the family's size "in policy." For these residents of a rapidly developing rural area, that meant sticking to two girls and giving up the chance to have a son.

The husband, Zhang Qing Ting, an electrical technician, said living in a modern subdivision for in-policy families beats the usual cramped apartments with no garages. He and his wife, Chen Hui Ping, a factory worker, will also be eligible for cash payments when they retire.

"Many of my friends envy me," Zhang said, mopping sweat from his neck as a dozen local officials and family planning bureaucrats looked on. The couple had been given a day off work to showcase the benefits of their restraint to two foreign journalists.

Jin Jing, chairman of Chao Le village, summed up the message: "If you practice family planning, you can get this kind of reward."

For more than three decades, the most populous nation on Earth has been running a massive social experiment, using elaborate incentives and penalties to limit family size.

The aim was to banish hunger and raise living standards, and by many measures the results have been impressive. By reducing the number of dependents per household and freeing more women to enter the workforce, population control efforts have helped lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty and contributed to China's spectacular economic growth.

Prosperity has exacted a steep environmental toll, however.

The colossal industrial expansion of recent decades has depleted natural resources and polluted the skies and streams. China now consumes half the world's coal supply. It leads all nations in emissions of carbon dioxide, the main contributor to global warming. Pollutants from its smokestacks cause acid rain in Seoul and Tokyo.

China's experience shows how rising consumption and even modest rates of population growth magnify each other's impact on the planet.

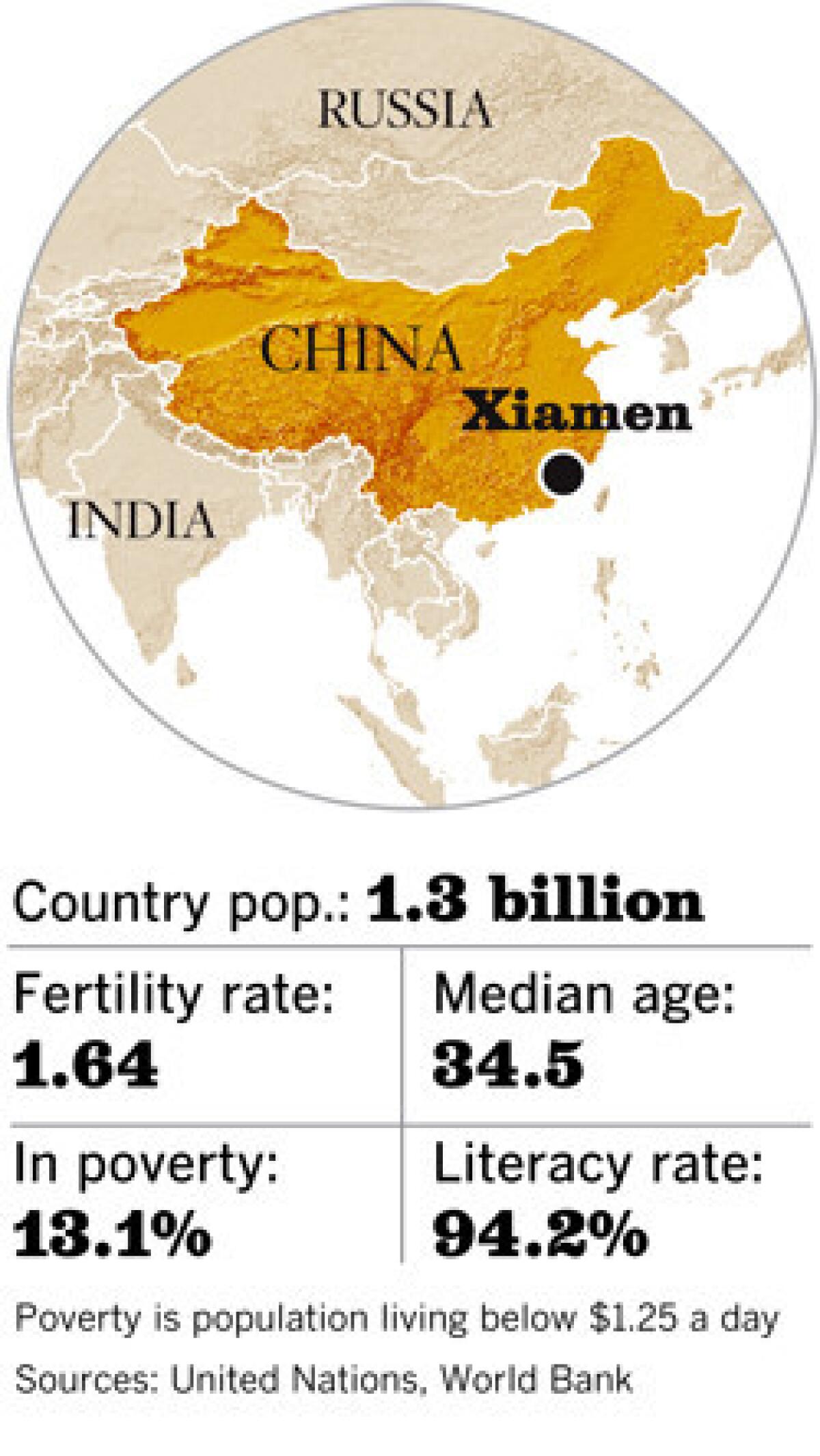

The country's population of 1.3 billion is increasing, even with the controls on family size. What is driving the growth is that hundreds of millions of Chinese are still in their reproductive years. On such a huge base, even one or two children per couple adds large numbers — an effect known as population momentum.

Moreover, the Chinese are living better overall: consuming more food, energy and goods than ever. One-fourth of the population — the equivalent of everyone in the United States — has entered the middle class.

The U.S. consumes much more per person. But with a population four times larger, China has a greater collective appetite — and a greater ecological impact — than any other country.

The compounding forces of economic and population growth are a source of increasing concern to scientists. An international team of 1,300 researchers organized by the United Nations concluded that evidence points to "abrupt and potentially irreversible changes" in ecosystems in the next few decades, including mass extinctions and rapid climate change.

Within China, signs of environmental damage are pervasive: massive fish kills, lung-searing smog, denuded landscapes. They have stirred popular discontent and the beginnings of greater official concern for curbing pollution and preserving natural resources.

How this drama plays out is not merely China's concern. Because of the nation's sheer size, the rest of the world has an enormous stake in the outcome.

"To solve China's problems is to solve the world's problems," said Yu Xuejun, a director-general in the country's National Population and Family Planning Commission.

China's massive population is a legacy of Communist Party Chairman Mao Tse-tung, who strove to increase the ranks of the Red Army by encouraging large families and banning imports of contraceptives and declaring their use a "capitalist plot."

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a series of famines claimed tens of millions of lives. The suffering left an enduring awareness that the country couldn't sustain unlimited population growth.

As Mao's power waned in the 1970s, other Chinese leaders applied the brakes. Free contraceptives were made widely available. Couples were encouraged to marry later, wait longer to have children and have fewer. In less than a decade, fertility plummeted from nearly six children per woman to fewer than three.

To drive the birthrate down further, Deng Xiaoping imposed the "one-child policy" in 1979. It led to mandated abortions and other abuses by zealous enforcers.

Today, there are many exceptions to the rule: Rural couples and ethnic minorities, for instance, can have two or more children. Although compulsory abortions have been forbidden, families must pay steep fines for having more children than allowed.

Yu, the family planning official, acknowledged that the policy has caused hardships.

"I myself sacrificed," he said, explaining that he forfeited his own dreams and disappointed his father by failing to produce a son. He and his wife had one child, a daughter.

There is widespread recognition [in China] that natural underpinnings of human prosperity are at grave risk.”— Gretchen Daily,

Stanford University ecologist

But he said such forbearance benefited the country, creating a bulge of working-age people with fewer dependents. The resulting burst in productivity is known as the demographic dividend.

Those who work for the vast family planning bureaucracy take great pride in what they see as their contributions to China's prosperity.

On a five-day tour of the homes of in-policy families, arranged for two Times journalists, officials toasted their achievements every night, feasting on dishes of beef, pork, duck, chicken and fish.

In discussing the country's population policies, the giddy bureaucrats turned again and again to the economic rewards. "We want to get rich before we get old," was a common refrain.

Nowhere is the scale of the country's transformation more vividly displayed than in its cities. Hundreds of millions of Chinese are moving from farms to urban centers to seek jobs and middle-class lifestyles.

In Shanghai, whose population of 23 million exceeds that of Australia, high-rises sprawl in all directions until their silhouettes slip from view, obscured by brown haze.

China, by varying estimates, has more than 100 cities with 1 million or more residents, compared with 9 in the United States. The number of million-plus cities will reach 221 within two decades, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, an economics research firm. More than a dozen will have populations of 25 million or more each.

On the family planning tour, Beijing organizers spoke of Yancheng, with a mere 8 million people, as a backwater. It's a former salt-harvesting town on the northern bank of the Yangtze River near the coast. Bustling shopping districts, new office buildings, housing projects and other development extend in every direction.

Away from the urban center, farms give way to neat rows of town houses and multistory condominiums.

All this development is being stitched together with high-speed rail and new highways to prepare for 600 million vehicles expected on the roads by 2050.

The U.S. automotive fleet, by far the largest in the world, is less than half that size.

China isn't hustling just to satisfy the demand from the United States and other countries for cheap merchandise. Increasingly, it is bent on meeting the needs of its own people.

More and more, it is being forced to confront the environmental consequences.

On the slopes above the Yangtze River headwaters, Chun Zhui and her family receive government money to forgo the usual crops and grow trees to help keep soil and rainfall in place. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

The misty hills of Yunnan province were once covered in pine trees. He Shigui remembers the hush of the fragrant forest when he was a boy.

All that changed when Mao instructed farmers to cut down the trees to grow food for a hungry nation.

Mao's slogan was "Man must conquer nature," and He Shigui and other farmers responded. By the 1990s, most of the trees along the Yangtze River were gone, along with the roots that once held the soil in place, creating a natural sponge.

He, his face now as furrowed as a field, still remembers the stormy day in 1998 when rainwater raced down the denuded hillsides, contributing to a disaster downstream.

"Of course I feel bad," said He, walking across the remains of a red-clay slope on his farm that washed away that day. "There was a flood here and there was a flood there. It was the same water."

The inundations across central China drowned more than 3,000 people, destroyed 13 million homes and caused at least $24 billion in damage.

The catastrophe also changed the way China viewed trees.

Chinese leaders issued a broad ban on logging and launched an enormous replanting program.

In the last decade, the government has spent more than $90 billion to plant trees across millions of acres and pay farmers to nurture them. An enormous sign just up the hill from He's farm proclaims, "Keep the trees, protect Mother Yangtze River."

The reforestation has turned China greener — literally. Scientists have noticed the change on satellite images: Forest cover has expanded from 12% to 20% of the country.

At least in this case, China learned the consequences of heeding Mao's exhortation to subjugate nature.

"Harmonizing people and nature — that's how high government discussions frame China's future development," said Stanford University ecologist Gretchen Daily, who has studied China's reforestation. "There is widespread recognition that natural underpinnings of human prosperity are at grave risk."

The solutions are not always as straightforward as planting trees.

Wang Xixhan tends a small garden at his home in the shadow of a steel mill in Linfen, an ancient city that in recent years earned the World Bank's dubious distinction of most polluted city on Earth. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times) More photos

A red truck arrived with a squeal of brakes and a swirling cloud of black dust.

The driver peeled back a tarpaulin to reveal his cargo: coal to stoke one of the massive electricity plants in Shanxi province.

The procession of dump trucks continued around the clock, leaking coal dust that piled up along the road like drifts of black snow. Squat cooling towers hissed like fumaroles. Slender smokestacks disgorged white-gray smoke carried east by the breeze, toward Beijing and beyond.

In nearby Datong, a thick gray-brown haze clings to the city like a dark mist, obscuring the tops of high-rises.

A half-day's drive south is the ancient city of Linfen, identified by the World Bank six years ago as the most polluted city on Earth.

The city, once known for its fruit and flowers, is now infamous for respiratory illnesses and the shroud of smog that regularly blots out the sun. When the sun does manage to poke through, it appears as a burnt orange fireball, reminiscent of Southern California's eerie skies during raging wildfires.

China likes to consider itself the world's factory. Yet it has also become the world's smokestack.

Tendrils of soot extend across the Pacific. On some days, almost 25% of the pollutants in the air above Los Angeles originated in China, the Environmental Protection Agency has found.

Under international pressure, China has cracked down on some of its dirtiest plants, mainly to reduce soot or pollutants like sulfur dioxide, which causes acid rain and aggravates asthma and heart disease.

After the World Bank's rebuke, officials in Shanxi province closed some of the illegal coal mines in Linfen and its dirtiest coal-fired furnaces.

Chen Mai Zhi, a stout middle-aged woman in black capri pants, said her headaches and dizzy spells have receded, but she still avoids wearing light-colored clothes and doesn't hang laundry outdoors because of the soot.

Wang Shu Quing has also noticed a difference. The smokestacks bordering her cornfield just north of Linfen no longer cough up black smoke. "They did something inside to change it," Wang said. "Now you can see the smoke only once in a while."

Such steps reduce pollution at the local level. But they do nothing to curb China's consumption of coal or the resulting carbon dioxide emissions.

China relies on coal to meet about two-thirds of its energy needs. Despite major investments in solar, wind and nuclear energy, coal consumption continues to climb.

Although China has the third-largest reserves in the world, it is reaching around the world for more. It overtook Japan this year as the world's largest coal importer, drawing mostly from Indonesia and Australia. Its imports are expected to double by 2015.

Those trends are worrisome to climate scientists, who say that in order to avoid a potentially catastrophic rise in global temperatures, worldwide carbon dioxide emissions must be cut in half by 2050.

For that to happen, China's emissions would have to peak by 2020, said Nobuo Tanaka, former director of the Paris-based International Energy Agency, which advises governments on energy issues. But by China's own projections, its output will rise at least 50% from current levels before peaking around 2035.

It would be all but impossible for other nations to compensate for such an increase, Tanaka said.

Chinese leaders say that capping emissions would cripple industrial growth and urban development in a country that still has 100 million poor people.

The industrialized countries polluted their way to prosperity, their argument goes, so why should the Chinese be penalized?

China's leaders also have sought credit for their population control policies, which they say averted 400 million births and thus billions of tons of greenhouse gas emissions.

At the same time, they acknowledge that the one-child policy was never meant to be permanent. When it was started in 1979, officials promised to revisit the issue in 30 years. There is some internal pressure and even more international pressure to lift the restrictions.

That worries Yu Xuejun, the director-general with the National Population and Family Planning Commission. The best course, he said, would be "a soft landing" with "incremental adjustments" so that the sacrifices he and others made in forgoing larger families are not erased by a baby boom.

"I cannot imagine if we had 400 million more people in China," he said.

About the series

Los Angeles Times staff writer Kenneth R. Weiss and staff photographer Rick Loomis traveled across Africa and Asia to document the causes and consequences of rapid population growth. They visited Kenya, Uganda, China, the Philippines, India, Afghanistan and other countries.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.