Population Day 4

Zhang Yujia, 6, watches cartoons in the house her parents bought in Chao Le village, in eastern China’s Fujian province, with a $100,000 interest-free government loan. The rural couple received the money as a reward for agreeing to stick to two girls and not try for a son. For three decades, the world’s most populous country has moved aggressively to limit its population growth. Yet the nation’s huge and still-growing numbers, along with its rising affluence, are taking a heavy toll on the environment. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

High-rises sprawl in all directions in Shanghai, a city of 23 million that is under constant construction. Barring windy days like this one, the buildings often disappear in a haze of brown smog. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Shanghai’s skyline forms the backdrop to visitors on the observation deck at the Oriental Pearl Tower. Hundreds of millions of Chinese are moving from farms to the nation’s cities in search of jobs and a middle-class lifestyle. The Asian Development Bank estimates that the ranks of China’s middle class will more than double in the next decade to 700 million. That growing consumerism is a key factor in the role China is playing in the planet’s future. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A family waits for a subway train after visiting Tiananmen Square in Beijing. China’s population is expected to grow until 2026, reaching 1.4 billion. That’s because so many Chinese are now in their childbearing years that even one or two children per couple will mean big increases. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Beijing’s subway system is a microcosm of the crowded capital. Nearly one-fifth of humanity lives in China. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Chinese authorities gave Zhang Runlian and her husband, Li Zhitian, a small red book with official stamps to show they are entitled to certain financial benefits for limiting their family size to just one child, daughter Li Yan. They run a small bed-and-breakfast in Yangshe, in Fujian province, which village leaders say has lifted itself out of poverty by preserving its forests and clamping down on population growth. The forests are now a tourist draw for city dwellers. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A coal-fired power plant spews smoke on the outskirts of Beijing. Most major cities in China are ringed by heavy industry, including iron ore smelters and concrete manufacturers. The country accounts for about half the planet’s coal use, and it is reaching around the world for more. China overtook Japan this year as the world’s largest coal importer. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Diesel exhaust and coal dust choke the streets of Taiyuan, capital of Shanxi province, where a procession of trucks delivers fuel to the city’s power plants. China relies on carbon-belching coal to meet about two-thirds of its energy needs. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A truck driver uncovers a load of coal that will stoke the boilers of a power plant in Taiyuan. Although the U.S. emits more carbon dioxide per capita than any other major country, and four times China’s per-capita rate, China’s large population and rapid industrial growth make it by far the world’s biggest overall generator of CO2. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Wang Xixhan tends a small garden at his home in the shadow of a steel mill in Linfen. The ancient city, once known for its fruits and flowers, in recent years earned the World Bank’s dubious distinction of most polluted city on Earth. After that rebuke, Chinese officials cracked down on some of the illegal coal mines in Linfen as well as its dirtiest coal-fired furnaces. Residents say things have improved — vegetables will grow now and people’s headaches and nausea have diminished. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

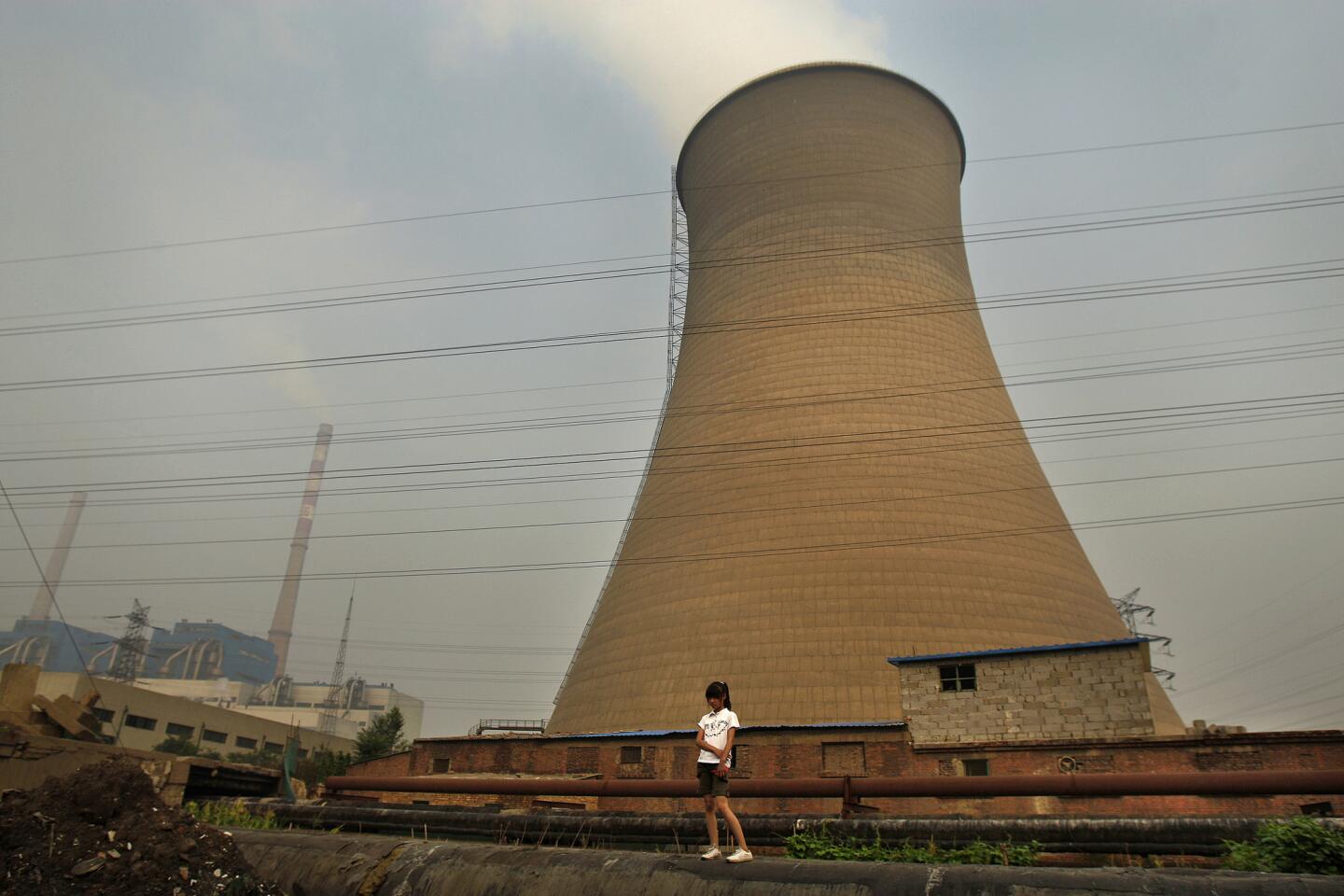

A power plant’s cooling tower looms over Guo Xin, 13, who lives near the plant in Taiyuan. The taller, slender towers emit carbon dioxide, soot and other pollutants. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has found that on some days almost 25% of the pollutants above Los Angeles originated in China. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Guo Tie Sheng fertilizes a field next to a coal-fired plant in Lingshi, Shanxi province, in the heart of China’s coal belt. The country’s growing use of coal is worrisome to climate scientists, who say that to avoid a potentially catastrophic rise in global temperatures, worldwide carbon dioxide emissions must be cut in half by 2050. China argues that it shouldn’t be penalized given that the world’s industrialized nations polluted their way to prosperity. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Workers tear out a street in Taiyuan to make way for something new. The nation is busily expanding its urban areas to accommodate the masses of people migrating from the countryside in search of a better life. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A swimmer braves the greenish waters of the Fen River, which runs through Taiyuan. Buildings in the background are partially obscured by the haze created by the coal-fired power plants that ring the city. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A herder grazes his goats in one of the many dry rivers in Hebei province, south of Beijing. China’s environmental problems are a powerful example of how population and economic growth together exact a much bigger toll than either would alone. It’s now understood that they magnify each other to deplete water, soil and other resources at an accelerated rate. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Farmer He Shigui walks past the remains of a red clay slope that washed away during massive flooding in Yunnan province in 1998. He and other farmers heeded the call of Mao Tse-tung decades earlier to cut down trees and plant crops to feed the growing nation. After the 1998 deluge that swept down denuded hillsides, killing more than 3,000 people, authorities issued a broad ban on logging and launched a massive replanting campaign. Farmers are now paid to nurture trees. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Despite China’s crackdown, illegal logging persists in the area of the devastating 1998 flood. China’s appetite for timber, paper and other forest products is huge. Most of it is satisfied by imports from Chinese companies snapping up natural resources around the world. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Stumps are all that remain on some of the steep slopes above the Yangtze River in Yunnan province. China’s reforestation efforts are making a difference: Scientists say satellite images show the nation’s forest cover has grown to 20% from 12% in the last decade. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

On the slopes above the Yangtze River headwaters, Chun Zhui and her family have given up growing the usual crops of barley, potatoes and radishes on one-third of their farm and tend to pine tree saplings instead. The government pays them to grow the trees to help keep soil and rainfall in place — and forbids them to grow other crops on the land. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A bicyclist rides past posters of trees in Beijing. The government has planted actual trees around the periphery of the city in an effort to control the dust that blows in from cleared land in outlying areas. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

Advertisement

No matter how crowded Beijing’s subway is, the traffic congestion above ground is far worse. China expects to have 600 million vehicles on its roads by 2050. The U.S. auto fleet, by far the largest in the world, is less than half that size. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

A train swings past row after row of apartment buildings stretching into the countryside around Beijing. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

A girl watches as a military color guard raises the Chinese flag at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. As China’s middle class has grown, so has domestic tourism and the Chinese market for food and luxury goods. “The world’s factory” today isn’t churning out cheap goods just to meet demand from the United States and other countries. Increasingly, it is bent on meeting the needs of its own people. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

In Uganda, population growth is also taking a toll on the environment, and that has led to a sharp rise in human-gorilla conflict. Around Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, one of the last refuges for the rare mountain gorilla, villages are exploding in size, resulting in deforestation and poaching. Barifa Benon, above, arrived too late to scare away a group of mountain gorillas that had destroyed his banana trees in pursuit of an easy meal. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

Advertisement

A patchwork quilt of subsistence farms has hemmed in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in southwestern Uganda. The poor landlocked nation, about the size of Oregon, has one of the world’s highest birthrates. Its population of 36 million is expected to triple or possibly quadruple by 2050. Researchers have determined that rural populations grow faster around national parks, as people are attracted to jobs, roads, schools and health facilities. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

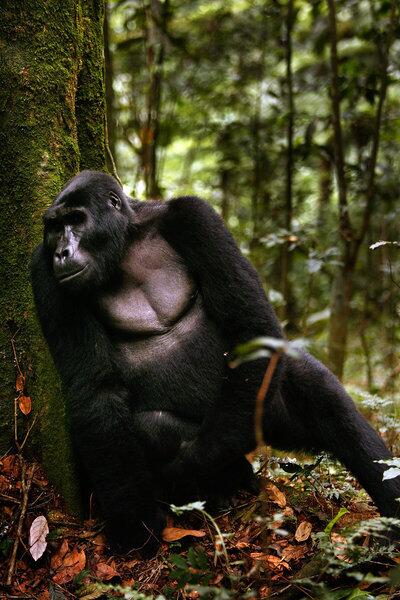

Fewer than 800 mountain gorillas remain on Earth. More than a third live in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, providing Uganda a major source of tourist dollars. Besides suffering loss of habitat, the gorillas are threatened by new ailments, such as measles and scabies, picked up from people who live around the park. Gorillas and humans are close genetic cousins, sharing 98% of their DNA. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

A volunteer trained by the nonprofit group Conservation Through Public Health prepares a shot of the hormonal contraceptive Depo-Provera for women living near the Bwindi park who want to avoid having more children. The family planning program was launched by a former government wildlife veterinarian who realized that the best way to protect the endangered mountain gorilla was to ease the pressure from fast-growing villages. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

Chimpanzees like this one — named Twig by researchers — have lost hands, feet and other extremities to poachers’ snares in southern Uganda’s Kibale National Park. Poaching has soared with population growth around the park, prompting Elizabeth Ross, the British wife of a Harvard primatologist, to found the Kasiisi Project, which works to slow the growth by improving local education and keeping girls in school. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

Advertisement

Girls at Kasiisi Primary School just outside Kibale National Park cheer on runners in a foot race. Attendance has soared at the 14 primary schools adopted by the Kasiisi Project. Typically, four out of five girls in rural Uganda never finish primary school. The country has the highest teenage pregnancy rate in sub-Saharan Africa, with half giving birth before age 18. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

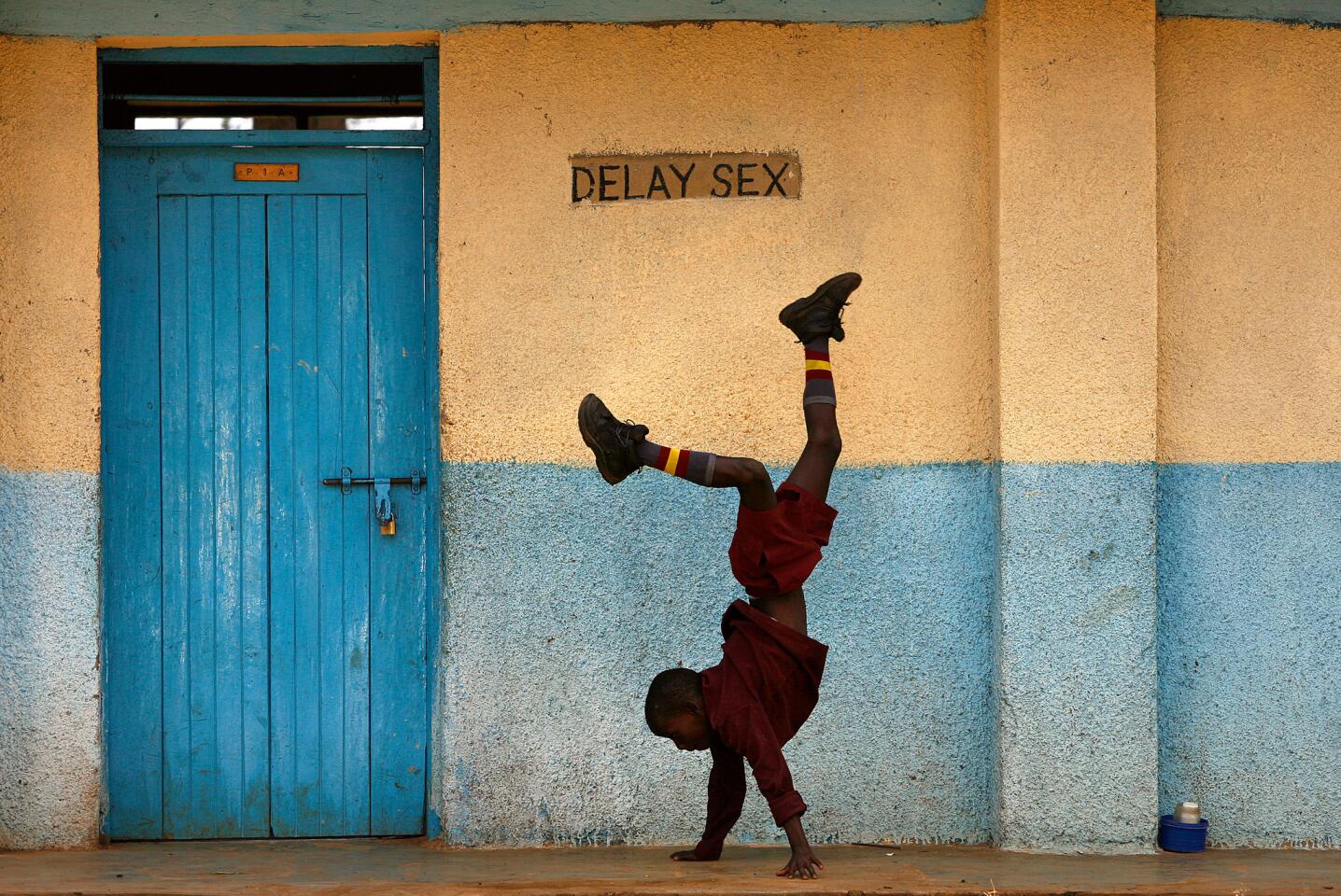

A boy does a handstand under a sign at the Kasiisi school, where students are taught abstinence as well as the importance of conservation in the adjacent national park. With better books, school supplies and trained teachers, Kasiisi and its sister schools have outperformed others in Uganda, showing vastly higher test scores and graduation rates. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

Kasiisi Project administrators were surprised to discover that it’s the small things — often taken for granted in developed countries — that can keep a girl in school. Gender-segregated restrooms and access to sanitary pads are now provided by its schools. Above, students line up in the office of the headmistress to ask for sanitary napkins. Previously, girls would have stayed home during menstruation or dropped out altogether. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )

A student of Kasiisi Primary School. In rural Uganda, girls often start school later in life and are well into their teens by the time they finish sixth grade. These days Kasiisi girls are doing as well as boys on tests and more are continuing their education at vocational and high schools. A few have made it to Makerere University in Kampala, the capital. In 2012, a Kasiisi student was accepted to attend Harvard. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times )