‘If we’re attacked, we’ll die together,’ a teenage anti-mining activist told her family. But when the bullets came, they killed only her

Topacio Reynoso was so precocious her mother sometimes joked she was an extraterrestrial.

A farmer’s daughter from a remote village in Guatemala reachable by a rugged mountain pass, she was playing perfect Metallica riffs on the guitar by age 12. She won beauty contests, filled notebooks with pages of heady poetry and moved through life with a fearlessness that made her parents proud — if also nervous.

At 14, she devoted herself to opposing construction of a large silver mine planned for a town nearby.

Topacio formed her own anti-mining youth group, wrote protest songs and toured the country talking about the environmental risks she believed the mine posed to her community. During a school trip to Guatemala’s capital, she led her classmates in refusing the small welcome gifts from a congressman who supported the mine. Then she heckled him so mercilessly that he fled the meeting.

The teenager’s efforts were not popular with everyone. Although some in the community worried chemicals used at the mine might contaminate nearby rivers, threatening the corn and coffee fields that have long been the region’s lifeblood, others said it would bring needed jobs and tax revenue. The community was split and violence was coming.

Topacio’s father, Alex, knew that speaking out could put the family in peril. Latin America is the most dangerous region in the world for environmental activists, with at least 120 killed last year alone, according to the nonprofit Global Witness.

But Topacio convinced him that it wasn’t a choice to oppose the mine, that it was an obligation: His father had left him land that was uncontaminated; it was up to him to pass on clean land to his kids.

He threw himself alongside his daughter into the fight.

These days, when he touches the bullet scars on his body or gazes at the memorial to Topacio that the family has erected on the porch, he wonders whether his decision was right.

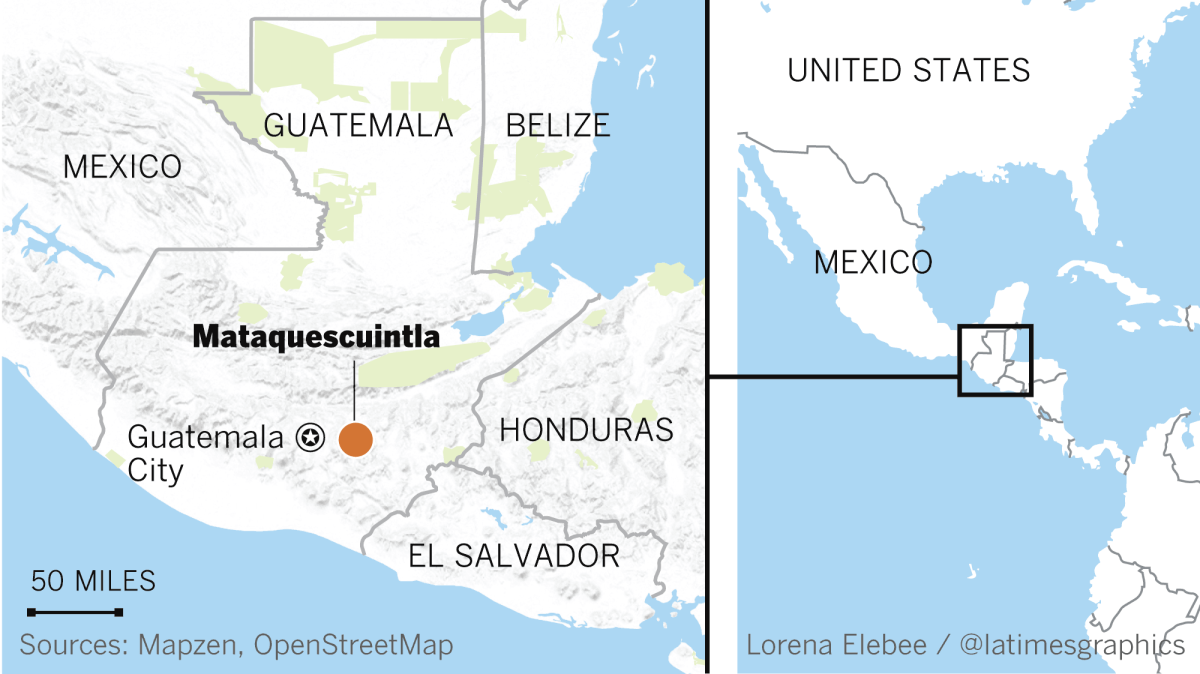

The small coffee farm where Topacio grew up might be one of the greenest places on Earth. Half an hour outside Mataquescuintla, a town of 30,000 in southern Guatemala, there are no neighbors in sight, just neat rows of coffee plants, then slopes planted with banana and palm groves, and up near the cloud line, towering pines.

Like her grandparents before her, Topacio grew up living off the land. The corn her family planted, dried and ground into powder was pressed into thick tortillas. Milk produced by a herd of bleating goats was churned into cheese. Yucca root plucked by her younger brothers was fried by her mother and served with salsa and rice.

Many nights, Topacio would sit on the porch or in her cramped, dirt-floor bedroom and strum the guitar, draw pictures and write poems. She filled a spiral notebook with drawings of the planet cracking open and butterflies flying out, and wrote verse after verse about “the betrayal of cowards” against “our generous Mother Earth.”

Nature, she scribbled in blue pen, “is a paradise where we sow dreams and reap happiness.” She dreamed of a day when “no hero will have to die in defense of his land.”

Controversy came to her community in 2010 when a Canadian mining company called Tahoe Resources bought El Escobal silver deposit for more than half a billion dollars. Located on about 250 acres of former farmland in a small town called San Rafael las Flores, just a few miles from Mataquescuintla, El Escobal had never been mined but was believed to contain one of the world’s largest caches of silver, along with deposits of lead, zinc and gold.

As Tahoe sought a license from the Guatemalan government that would allow it to start pulling ore from the earth, some locals fought back. They complained the environmental impact report commissioned by Tahoe didn’t adequately assess all the risks to the region, and said the company hadn’t properly consulted with community members — though the company said it had thoroughly evaluated the impacts and had won popular support.

It was 2012 when Topacio went to her first protest, a demonstration outside the mine entrance organized by the local Catholic diocese. It transformed her, said her mother, Irma Pacheco. The people she met while protesting were deeply principled, she told her parents, especially an articulate teenager with a kind face named Luis Fernando, who would become a close friend.

Soon Topacio had persuaded her parents to join “the resistance,” as locals called the anti-mining effort. Although the idea made her father nervous, he was well suited to bucking the local establishment. Growing up, he had often fought off bullies unnerved by his long hair and taste for black clothes and heavy metal music that carried a strong political message. In rural Guatemala, most men favored cowboy hats and tight jeans with a gun tucked into their waistband — and listened to brassy ranchera.

Ahead of a 2012 referendum in Mataquescuintla that asked locals whether they supported the mine, Topacio and her father traversed the countryside on behalf of the “no” campaign. They were successful: More than 98% of voters said they opposed it. There were similar outcomes in referendums in several other towns. Tahoe executives argued that the votes were nonbinding. The company poured millions of dollars into the community to demonstrate the project’s benefits, opening a vocational center for young people, giving out free vaccines for livestock and planting tens of thousands of trees.

The mining project had supporters in high places. Decades of civil war had killed 200,000 people and limited international investment in the country. After peace accords were signed in 1996, Guatemala’s leaders saw the expansion of mining as an opportunity to get the country back on its feet again. The Ministry of Energy and Mines has approved 307 active mining licenses and is considering 599 more.

In April 2013, Minera San Rafael, Tahoe’s Guatemalan subsidiary, was granted a 25-year exploitation license. Mining could officially begin.

In the nearby communities, it was the most violent spring many people had experienced since the war.

That March, four leaders of the local Xinca tribe were kidnapped by unknown assailants on their way home from campaigning in favor of a referendum on the mine in San Rafael. Three were released, but another, Exaltacion Marcos Ucelo, was found dead the next day. No one was arrested in connection with the crime. The office of Guatemala’s attorney general said it is still investigating the case and could not provide information about possible suspects or motive.

The next month, seven protesters who had gathered peacefully for a demonstration outside the mine were shot by the mine’s private security workers. In a civil lawsuit filed in Canada, the wounded men say they were shot with lead bullets, some of them at close range, as they were attempting to flee.

Among those badly injured was Topacio’s friend, Luis, who was shot three times in the face. After multiple operations, he still has difficulty breathing.

The mining company says the guards used rubber bullets, not lead bullets. It also said the company security chief who ordered the response, Alberto Rotondo, was acting outside the scope of his authority and has been dismissed. “Rotondo violated the company’s rules of engagement, security protocols and direct orders,” Edie Hofmeister, Tahoe’s executive vice president of corporate affairs, said in a statement.

“We condemn violence of any kind in the strongest possible terms, and moved swiftly to fire him after this incident,” the statement added. (There has been no evidence presented of any company involvement in Topacio’s death; asked about her family’s belief that it was due to the teenager’s work as an activist, Tahoe officials reiterated their strong message to employees that violence will not be tolerated.)

In May, Guatemala's then-president, Otto Perez Molina, moved to quell the instability that mine officials complained was disrupting their business. Citing the threat of terrorism and criminal groups, Perez declared a “state of siege” in the communities near the mine, deploying thousands of troops and temporarily suspending constitutional rights in the region. Several prominent anti-mining activists were arrested.

Rotondo fled to Peru and is awaiting extradition to face charges in Guatemala.

Alex Reynoso thinks he would have been detained too, except for a fortunate mix-up: Although everyone in town knew him as Alex, his real first name was Edwin. When he showed his identity documents to police, they let him go.

Topacio’s parents were growing wary of the threat of worsening violence, but she pressed them to keep fighting. They laughed when she told them about telling off the pro-mine congressman, and looked on in awe when she approached the Mataquescuintla mayor to ask for money for her youth group, and he agreed. When a family friend gave her a silver ring to congratulate her on her high school graduation, she refused to wear it.

Topacio told her family she felt more comfortable when they were together in public. “If we’re attacked,” she said, “we’ll die together.”

On April 13, 2014, Topacio performed with her marimba band at a local festival. Her mother, who was pregnant at the time, went home because she wasn’t feeling well. A little after 9:30 p.m., the teenager and her father started walking to their car to head home. Unknown gunmen sprang from behind and opened fire. A few hours later, Topacio was dead.

Her father slipped into a coma that lasted several days, but he eventually regained consciousness. The next year, after leaving an event celebrating the anniversary of his town’s anti-mine referendum, he was attacked again, this time with a carload of three other activists. They all survived.

Why they were targeted remains a mystery. Police investigations into both attacks have yielded nothing, despite a letter signed by 36 international human rights organizations demanding that Guatemala's attorney general seek justice for the attack that killed Topacio.

Impunity for killings is normal in Guatemala, where the justice system has been crippled by a lack of resources and corruption. At the national level, the United Nations-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala has led important efforts against graft, including a 2015 investigation that led to the resignation and jailing of Perez, the president who had ordered troops to the communities around the mine.

Topacio’s parents believe the shooting was connected to their activism, but they acknowledge that in a region that had become polarized over the mine, anyone could have pulled the trigger. And in a violent country such as Guatemala, which has one of the highest homicide rates in the world, it could have been something else — a grudge, a case of mistaken identity or just an echo of Guatemala’s violent past.

Topacio was buried in a colorful hilltop graveyard, alongside her grandparents.

Every year, during Dia de los Muertos, her parents come and lay down a new wreath of flowers assembled in the shape of a butterfly. “You are present in the stars every night/your pupils brightly illuminated in the sky,” reads the poem written on her gravestone. “You will live forever because your dreams were just and your struggle inspired life.”

Topacio’s legacy continues to grow. There’s a mural of one of her drawings on a wall downtown that shows a young woman with wings and the earth splitting open, spilling butterflies. A Canadian-based environmental group has started giving out a scholarship in her name, and activists in Toronto have honored her in the streets, toting posters that say “Rest in Power, Topacio.”

At a recent event in Mataquescuintla, the mayor encouraged his constituents to continue their opposition to the mine. Her old friend Luis, his face disfigured by bullet wounds, led a group of young protesters in a rallying cry.

“Where is Topacio?” he shouted.

“In these streets!” the group yelled.

Operations at the mine were halted this year. In July, the company’s license was temporarily suspended after Guatemala’s Constitutional Court ruled that the company should have first consulted with the indigenous Xinca people. Then a group of protesters armed with stones and machetes set up a roadblock on the main highway into town, prohibiting mining vehicles from passing.

The suspension has delivered a massive financial hit to Tahoe, which listed no silver output and a loss of $8.4 million in the third quarter of this year. Those who had come to depend on the mine are also suffering.

After the mine opened, San Rafael restaurant owner Yanet Pozuelos opened a second location to help serve hundreds of mine employees. Since mining has halted, her business has fallen 60%.

“The mine helped us so much,” Pozuelos, 49, said. “We’ve never had a business that gives this many jobs.” One benefit, she said, is that it keeps young people from leaving for Guatemala City or the United States to find better-paying work.

Hofmeister said the company hopes it can comply with the necessary legal requirements and resume production. “With operations resumed, we can continue making significant investments in the country, which benefit thousands of Guatemalans,” she said in her statement.

The mine has “helped the area to flourish,” she said.

On the coffee farm where Topacio lived, her death is ever present.

Large posters the family had made for her funeral hang on the walls. On the porch, a montage of large photos show Topacio at a water park, Topacio receiving her beauty queen sash, Topacio dancing with her father.

Her bedroom is untouched, even though her younger brother now sleeps there. Her guitars hang proudly on the walls. A boombox and a collection of CDs collect dust.

After the attack, her mother came here to cry alone. On a recent afternoon, Pacheco, now 42, entered for a moment of quiet contemplation.

She touched a pair of white leather sandals — the shoes Topacio was wearing when she died. She held up the blouse from that night and smoothed out the pair of jeans that she had scrubbed free of blood. Then she folded them all up again, tucked them in a drawer and walked outside, surrounded by green.

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

Twitter: @katelinthicum

ALSO

He defended the sacred lands of Mexico’s Tarahumara people. Then a gunman cut him down

'They should be thought of as heroes': Why killings of environmental activists are rising globally

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.