A Philippines grandmother fought to get a toxic coal stockpile out of her neighborhood. Three bullets stopped her

Gloria Capitan couldn’t have imagined her fate. Her cause felt just, and her community was behind her. Besides, who would kill a 57-year-old grandmother?

It had been a long two years. Since 2014, a coal stockpile down the road had been polluting her town, Lucanin, sickening her family and covering the coastline in ash. Capitan, like a Philippine Erin Brockovich, was campaigning for its closure when a mysterious man began visiting her at home and making vague threats of violence.

It happened on July 1, 2016, around 8 p.m. Capitan was in her small karaoke bar, a one-minute walk from her house, singing a saccharine pop ballad with her 8-year-old grandson, Jerson. Two men on a motorcycle pulled up outside. One entered, a yellow handkerchief covering his face. He shot Capitan three times — once in the arm, twice in the neck — then he fled. Jerson looked on, screaming.

“Everybody cried when they saw Gloria,” Jerson said later, as his parents nodded, their eyes downcast. “Then we left the place. We went down to the house. But no police came.”

The world is experiencing an epidemic of environmental killings, and it’s getting worse.

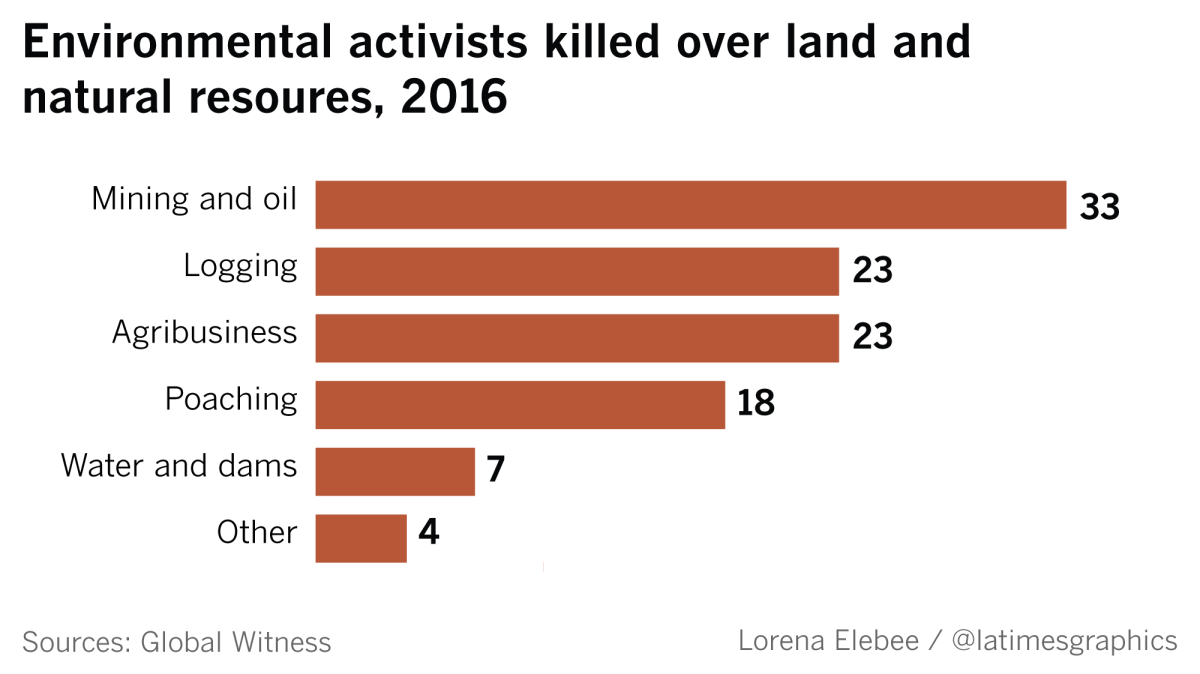

In 2016, 200 environmental defenders — anti-mining activists, indigenous protesters, workers for nongovernmental organizations — were killed worldwide, according to the London-based nonprofit Global Witness, more than any year since the organization began collecting data in 2002. This year, an estimated 150 had been killed by October, meaning the toll could be higher.

In Asia, the Philippines topped the list. At least 28 Philippine environmental defenders were killed in 2016, most of them anti-mining activists. This year, the death toll has reached 18, according to Global Witness.

In January, Mario Contaoi, a radio reporter, university lecturer, and outspoken environmentalist, was shot while riding his motorcycle. In February, Renato Anglao, an indigenous activist on the southern island of Mindanao, was killed while fighting efforts to establish a plantation on his ancestral land. In March, Ramon Dagaas Pesadilla, an anti-mining activist, also on Mindanao, was shot to death at home with his wife.

Billy Kyte, a Global Witness campaigner, said the rise in killings may have been inspired by President Rodrigo Duterte, who has promised to rid the country of illegal drugs — and in the process, has encouraged a rash of extrajudicial killings. The president has also targeted human rights activists. “One of these days, you human rights groups, I will also investigate you,” Duterte said in August. “If they are obstructing justice, you shoot them.”

In the 18 deaths this year, no perpetrators have been identified.

Bataan province, population 760,000, is a swath of emerald hills and fishing villages not far from the Philippine capital, Manila. Internationally, it’s best known as the staging ground of the Bataan Death March, in which Japanese troops forced defiant American and Filipino soldiers inland during World War II. At home, it’s also known as a hub for power generation.

The Philippines is one of Asia’s fastest-growing economies, and its government is exploiting cheap, convenient fossil fuels — especially coal — to fuel that growth. The country has 32 coal-fired power plants, and it’s planning an additional 25 by 2030.

Bataan is home to three coal-fired power plants and one oil refinery, which together generate more than 2,000 megawatts of electricity, enough to power 1.3 million American homes (and many more Philippine ones). They’re owned by both local and international companies; one plant is owned by the domestic San Miguel Corp.

With new projects planned in coming years, the province’s energy output is expected to more than double, but as with coal plants around the world, the extra power comes at the cost of unhealthy air emissions and a sprinkling of soot. Power plant owners said they were working to hold down emissions, but even the cleanest plants mean more pollution — and Bataan now has plenty of them.

“The power plants here, they're like mushrooms after rain,” said Alvin Pura, 37, a landscaper in the town of Limay.

The power plants here, they're like mushrooms after rain.

— Alvin Pura

Capitan was a hard worker with a simple life. Her 60-year-old husband, Efren, suffered a stroke in 2013, leaving her with outsize responsibilities in supporting her five children and 18 grandchildren. She cooked, cleaned, collected firewood, took care of Efren, and bred pigs. In 2014, she opened a roadside convenience store, a two-minute walk from her home, where she sold sodas and French fries for additional income.

That’s where the conflict with the energy companies started. A thin patina of black coal dust, almost certainly from a nearby stockpile, had begun covering the countertops and floor of her store. Capitan would clean it, but the toxic dust would always return. That May, the Mariveles sanitation department inspected her shop and ordered it closed.

The inspector was sympathetic. He advised her to lodge a complaint against Seafront Shipyard and Port Terminal Services, a Philippine company that helps supply nearby power plants with coal and cement imported from Indonesia. That year, Seafront had opened the coal stockpile a short drive from Capitan’s home — a long pier covered in heaps of the fossil fuel.

Capitan decided to act. She circulated a petition calling for the stockpile’s closure, and about 1,000 people signed it. Yet the company didn’t respond, so in January 2015, she formed a loose-knit advocacy group — the United Citizens of Lucanin Assn. About 30 neighbors joined.

“There were so many people that she heard complaining about the same problem,” said Capitan’s daughter Jovelyn, 30. “She thought, ‘Why don’t we put ourselves together, and maybe we can find our strength?’”

Meanwhile, the pollution seemed to be getting worse. Her grandchildren suffered constant asthma attacks, chest colds and skin rashes. Her mango and coconut trees withered, their leaves thick with dust. When it rained, black sludge dripped from the rooftops and formed puddles in her courtyard.

Capitan threw herself into her cause. She petitioned, protested, deluged the company with calls. She continued to run the family business, converting her shop into a karaoke bar, which didn’t require such strict health certification from the city.

In November 2015, she participated in a climate change advocacy march in Manila, where activists talked about how burning fossil fuels wasn’t just causing local pollution — it was contributing to a dangerous increase in average temperatures. “She was crying beside me in the march — weeping,” said Derek Cabe, coordinator of the Coal-Free Bataan Movement, another NGO. “She said she didn't know this thing was so big, so huge, compared to [her] problem, which is so little. She was inspired.”

Capitan’s advocacy had some impact, at least while she was still alive. In May 2015, in response to Capitan’s petitioning, Mariveles’ sanitary inspector ordered Seafront to cover its coal stockpile, and the company installed a large, warehouse-style structure on the pier, reducing atmospheric dust.

Yet problems remained. To this day, coal-hauling trucks still kick up dust, said Ermin Hatol, 71, a neighbor of Capitan. Occasionally, the company burns coal and chemicals at the stockpile, creating a foul, rotten-egg stench, after which many people report stomach problems and migraines, said Cabe. (Seafront did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Mercy Tihim, who works at a clinic not far from the GNPower Mariveles coal-fired power plant, said reports of pneumonia, coughs, skin rashes and tuberculosis skyrocketed after the plant began operations in 2014. Last year, she said, at least nine cases of child tuberculosis were recorded. In the first half of 2017, there were four. “Before, we had incidences, but it was very few,” she said. “Now things are different.”

Officials from the power plant declined to comment on the health reports.

A short drive away, in Limay municipality, locals complained that a 600-megawatt expansion at the San Miguel-built coal-fired power plant had destroyed several vegetable farms, and about 2,000 trees, due to soot pollution. In December 2016, the Philippines Environmental Management Bureau sent a notice of violation to the plant, ordering it to halt emissions while activists’ claims of environmental pollution were investigated.

In January, the company deployed doctors to aid nearby residents, the Philippine Inquirer newspaper reported; in February, it said that its emissions registered as “way below” World Bank and government standards. Company President Ramon Ang denied that pollution from the plant was causing health problems. There is “no smoke, no pollution there,” he told the newspaper. “We’re committed to help the environment.”

Yet months later, residents were still complaining about pollution. “I worked in the plant for a month, and I think I got sick seriously because of the plant,” whispered Gerald Respicio, a deathly thin 26-year-old, as he lay in his home near the plant, recovering from tuberculosis. He said he has received no compensation. His direct employer at the time, the contractor SM Blooming Phils, could not be reached for comment; its one publicly listed number is disconnected. Respicio and a Philippine corporate records website said the company has since closed.

In April 2016, a man who would not fully identify himself visited Capitan at her home, according to her son, Mar, 35, who was present during the encounter. The man gave his name only as Alex, and refused to say who had sent him. He vowed to give Capitan’s husband, Efren, a $300 medical allowance for top-notch treatment in Manila — but only if she stopped her anti-coal organizing activities. “I care about all of you,” Mar heard him say. “I’d hate to see any of you buried under a mound of earth.”

“Her answer was a big ‘no,’” Mar recalled. The man came to the house “three or four times” altogether, Mar said, but each time, Capitan rebuffed him.

In May, Carlo Ignacio, Seafront’s vice president for operations, called Capitan to his office. Several members of Capitan’s association — including Nanding Fernando, 65 — waited outside as they met, Fernando said. Afterward, she recalled, Capitan told the group that Ignacio had urged her to halt her group’s demonstrations.

“He was slamming the table. He told her you should stop, you should stop because you're not making things better for yourself or your village,” Fernando said. “Gloria told us she was basically — she felt threatened.”

It is not possible to verify firsthand what happened in that meeting — Ignacio did not respond to repeated attempts to contact him. Four public numbers for Seafront were disconnected, and a Los Angeles Times reporter was turned away at the company’s guarded compound in Mariveles. One Seafront employee, reached via intercom, said that only Ignacio could comment on the case — but Ignacio was not available.

In a July 2015 article in the Manila Bulletin, Ignacio criticized an unnamed family — most likely Capitan’s — for launching a petition against the coal stockpile operated by Seafront. “It is not us who will suffer severely but it is the public (due to power shortage) if the shipment of coal is stopped just because of the whims and caprices of this couple,” he told the newspaper.

In the Philippine press, the company has defended its record on community involvement, while sidestepping allegations of pollution. Seafront donated two fishing boats to two groups of fishermen, “complete with fishing gears and gadgets,” the newspaper Punto! Central Luzon reported in 2015.

That year, the Manila Bulletin newspaper reported that Seafront had constructed churches in Bataan “worth millions of pesos,” sponsored charity healthcare projects and donated food to malnourished children. The article did not address citizens’ complaints about pollution, but reported that Seafront had been providing direct and indirect employment to 1,500 locals.

“Heaven knows what we’ve been doing,” Ignacio told the newspaper.

It seemed clear that someone was targeting Capitan. On the day after Duterte’s inauguration, Efren and Mar were sitting at home in the evening when they heard three gunshots. Mar ran to the bar and saw his mother’s head tilted back, blood pouring from wounds in her neck. He and his brother Jerson jumped on motorbikes and chased the killers, but soon lost sight of them. Then they went to the police.

The police, Efren said, seemed reluctant to investigate. “There was speculation around the community that maybe she was killed because of drugs or a land dispute,” he recalled. “They didn't want to admit it was because of the environment.” He said police didn’t even investigate the crime scene; family members retrieved the bullets themselves.

Loyd Opeña, chief investigator for the Mariveles police, denied that account. He said detectives are building a case, and have identified a suspect; a warrant of arrest, he said, will be served “soon.” He suggested that the force considers Capitan’s case sensitive. "The victim is a leader of a pro-environment group, that's why the community is aware of the case,” he said.

He said the police never received a formal complaint from the family, and had to open one themselves in order to launch their investigation.

Mar said the family had little confidence that filing a complaint with the police would lead to an arrest — and confronting the authorities might cause the family more trouble, he said. Efren’s medical condition hasn’t improved, and “we don't want another parent to die because of stress and pressure,” Mar said.

“We think Gloria is already at peace now, and we're scared for our children,” he said.

Soon after Capitan’s death, the local citizens advocacy group disbanded. “Of course if you know Gloria,” Mar said, “she'd be very, very sad.”

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

Special correspondent Yas Coles contributed to this report.

For more news from Asia, follow @JRKaiman on Twitter.

ALSO

In one of Africa's most dangerous corners, a fight to the death for the elephants

'If we're attacked, we'll die together,' a 16-year-old anti-mining activist told her family

He defended the sacred lands of Mexico’s Tarahumara people. Then a gunman cut him down

'They should be thought of as heroes': Why killings of environmental activists are rising globally

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.