England’s King Richard III to be buried in Leicester, court rules

Reporting from London — Nearly 530 years after the death of Richard III in battle, Britain’s high court ruled Friday that the king immortalized by Shakespeare as a misshapen, murderous villain is to be buried in Leicester, the city where his skeleton was found beneath a parking lot in 2012.

The court dismissed a competing campaign by some of the deposed monarch’s distant relations to have him interred in York, in northern England, which they argued had a stronger claim on his affections – and his bones.

“It is time for Richard III to be given a dignified reburial, and finally laid to rest,” the three justices who heard the case wrote, paving the way for the long-ago ruler to be interred in Leicester Cathedral.

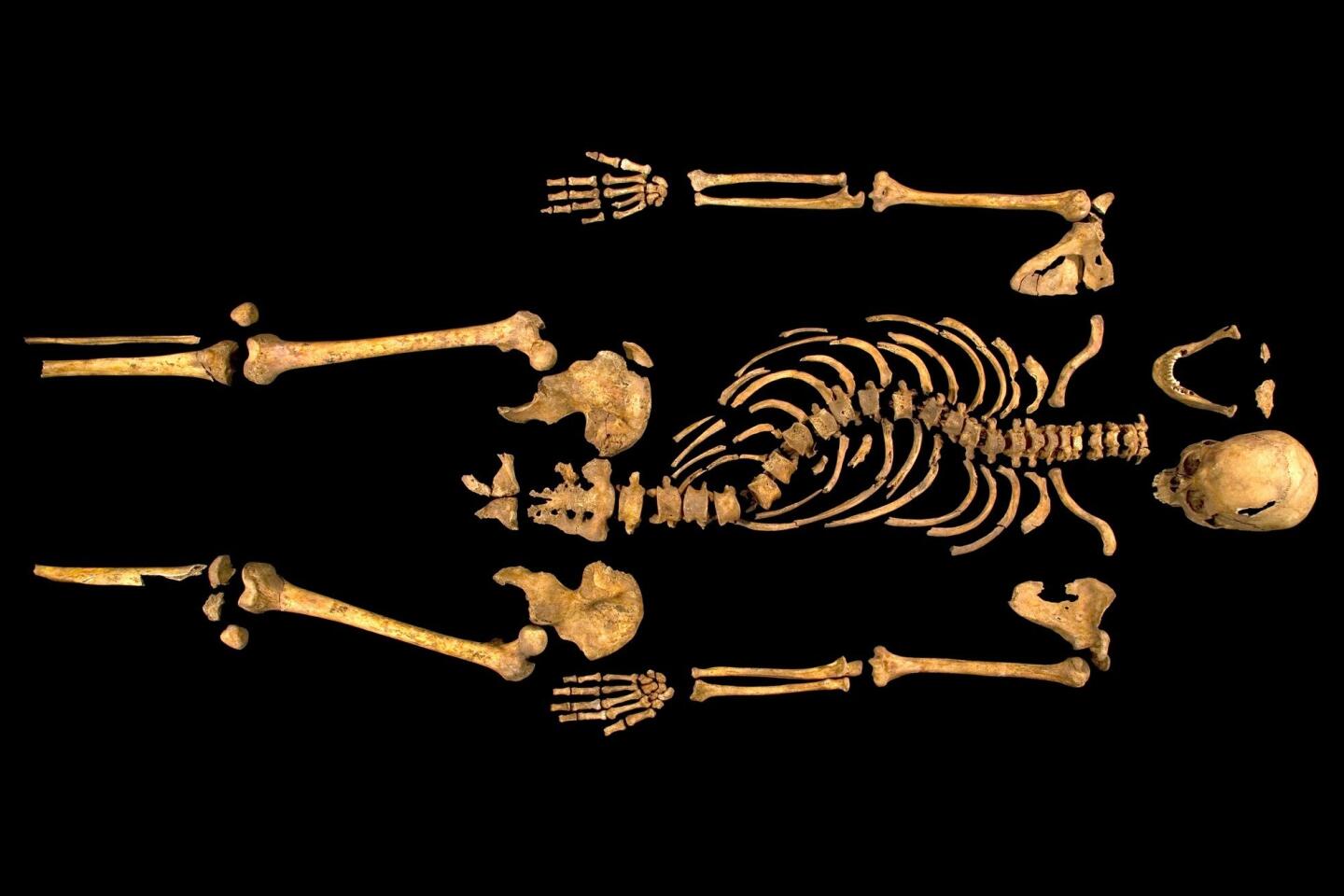

The cathedral stands a stone’s throw from the site where, working off of old maps and improbable hopes, archaeologists dug in search of the last recorded place where Richard’s body was buried, beneath the floor of a lost medieval church. In an almost miraculous find in September 2012, on one of the few bits of land not built over in downtown Leicester, they unearthed the skeleton of an adult male who had clearly suffered grievous battle wounds.

DNA and other tests proved that the remains belonged to Richard, the final Plantagenet king and the last English monarch to die in combat. He was killed Aug. 22, 1485, at Bosworth Field, outside Leicester, in a climactic fight that ushered in the long reign of the Tudors, including Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.

Almost as soon as the remains were found, however, another battle broke out, over where they ought to be laid to rest.

A group called the Plantagenet Alliance challenged the decision to rebury Richard in the nearby cathedral, arguing that York would be more appropriate, since he spent much of his childhood and early adult life in and around that city. The group accused the government of failing to consult widely enough before it granted the burial license to Leicester.

But in what it called a “unique and exceptional” case, the high court Friday upheld the government’s decision. Despite the “trenchant views expressed by rival factions,” the court noted that officials had followed proper protocol regarding discovered remains; that Henry VII, Richard’s successor, had buried him in Leicester; and that the present queen, Elizabeth II, appeared content with the idea of keeping him there.

While an appeal of the ruling is technically possible, David Monteith, the dean of Leicester Cathedral, described the court’s judgment as “clear and unequivocal.”

“He fell here. He’s lain here for over 500 years. The cathedral is about 150 meters from the site of discovery,” Monteith said in a telephone interview.

Despite Richard’s strong ties to York, “as a king of England in medieval times he spent time all across England,” said Monteith. “He knew the city of York well, but he knew the city of Leicester well. He didn’t leave any will saying [where] he should be buried…. We’re simply doing what the law requires.”

In a statement, the Plantagenet Alliance expressed disappointment with the ruling but said it had tried its best to “persuade the decision-makers to reconsider public consultation regarding the final resting place of the last Plantagenet king of England.”

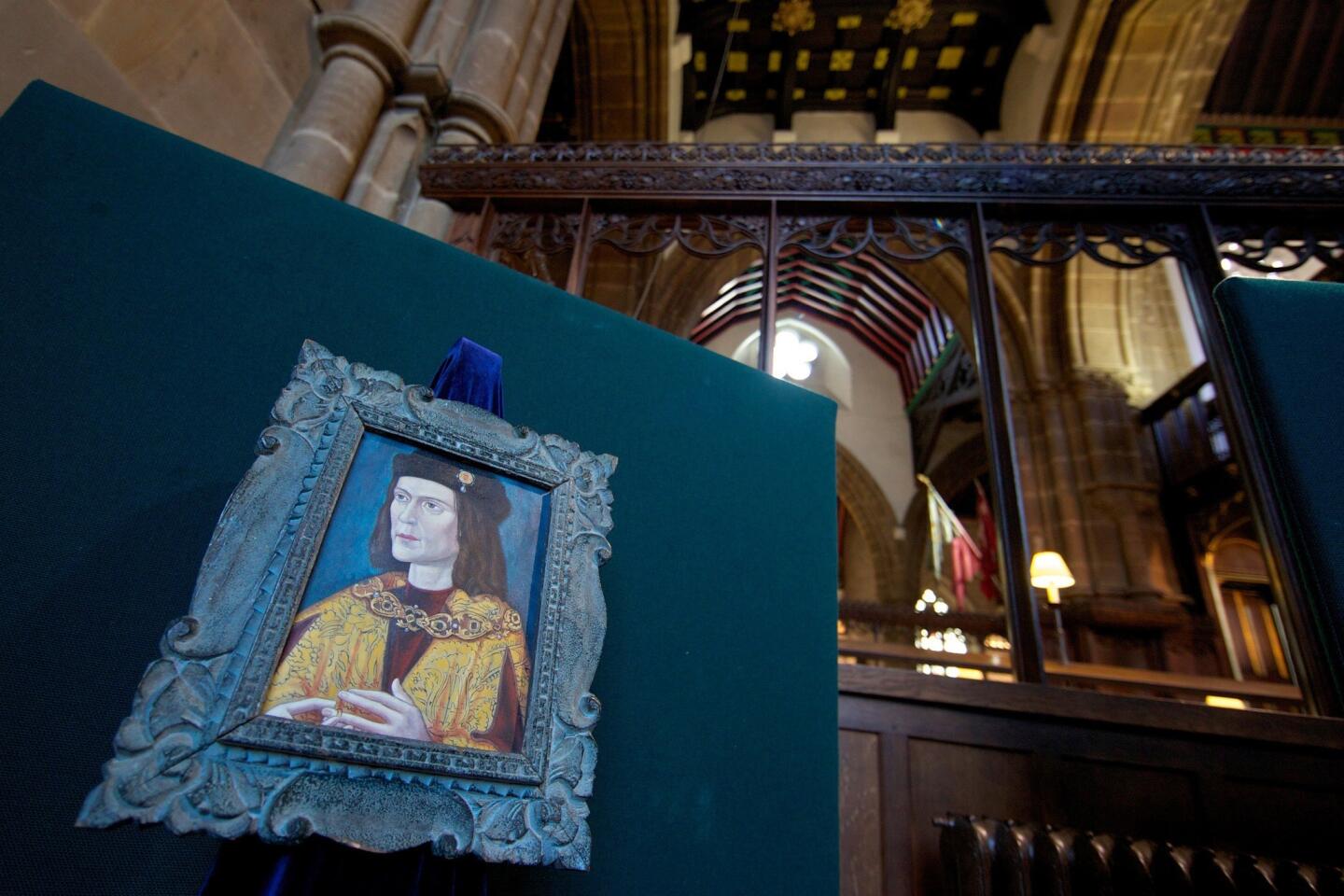

Leicester Cathedral has already gone to some expense to prepare for a re-interment, tentatively scheduled for spring of next year. A new tomb will be erected in the heart of the church, replacing the existing memorial marker, and planning is underway on a solemn service befitting a man who was England’s “anointed king.”

He’s also one of its most controversial. Scholars and amateur historians are bitterly divided over whether Richard was the bloodthirsty tyrant depicted by Shakespeare who had his two young nephews executed in the Tower of London so that he could claim the crown for himself, or an enlightened ruler who instituted lasting legal reforms but whose name was indelibly smeared after his death by Tudor propagandists.

No matter where he’s buried, that is one debate that will probably never be put to rest.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.