‘The Lost King’ highlights the buried history of the woman who found the remains of Richard III

In 2012, the bones of King Richard III were excavated from a parking lot in the city of Leicester, England.

For years, historians and academics had searched for his final resting place following his death in 1485 in the Battle of Bosworth Field. Some believed his tomb was lost, while others were convinced he was tossed into the nearby River Soar. But Philippa Langley, an amateur historian living in Edinburgh, followed research and instinct to uncover his long-lost bones.

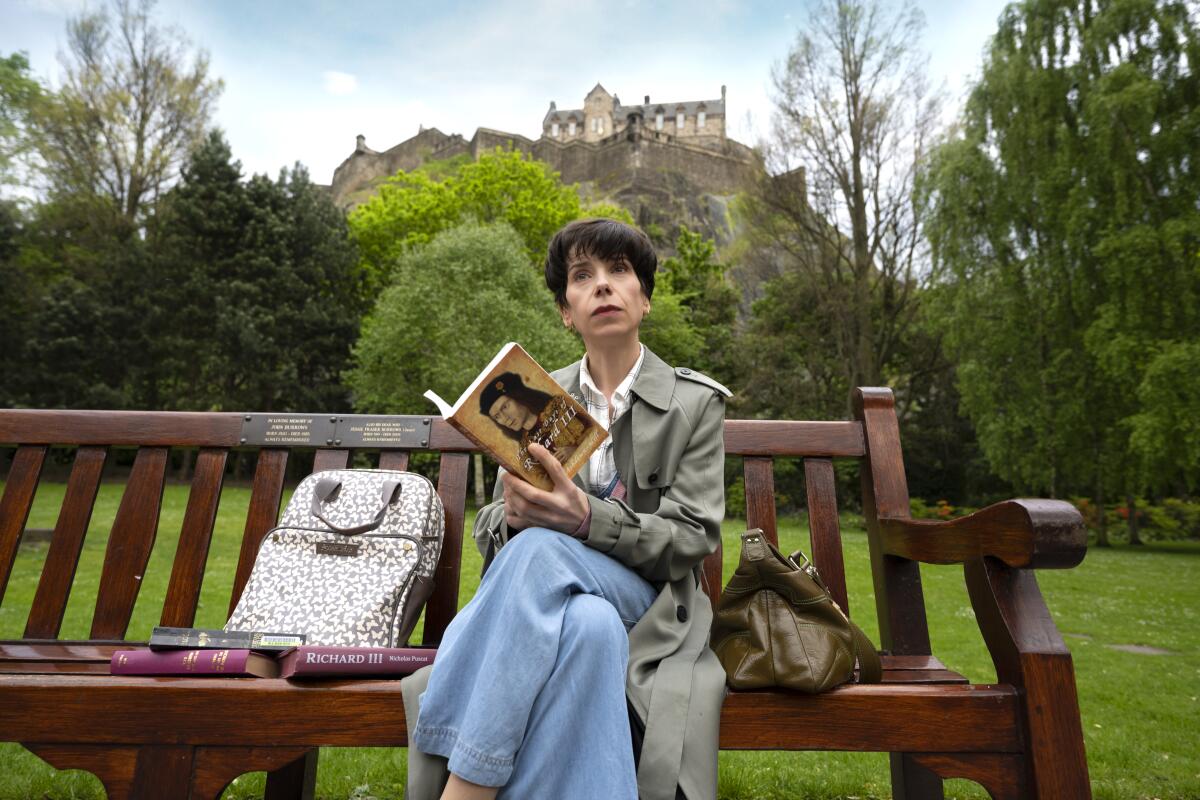

Langley’s story has become filmmaker Stephen Frears’ latest effort, “The Lost King.” Written by Steve Coogan and Jeff Pope, the film reconstructs the search and discovery of Richard’s remains by Langley, played by Sally Hawkins. It also details how she was pushed to the side by the University of Leicester, which has taken most of the credit for the discovery.

“It sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it?” Pope says of the story. “Middle-aged housewife from Edinburgh finds 500-year-old king mostly by intuition. And then a lot of kudos and credit for that are taken away from her. Steve and I both felt very strongly that it was unfair and that this movie was part of Philippa’s journey.”

Archaeologists have till Sunday to hunt for the bones of Richard III, a king synonymous with villainy, under a Leicester parking lot.

Coogan connected with Langley eight years ago after seeing the documentary on the story, “Richard III: The King in the Car Park.” In the years since, he and Pope kept coming back to the idea.

“When she told me what happened to her I wanted to tell her story because I felt like she had been marginalized,” Coogan explains. “It was a typical case of patriarchal marginalization of a woman who had taken the initiative and then just had it wrested from her in a way that made me mad.”

Coogan and Pope did extensive research and spoke with many of the real people involved, including Langley, her family and Richard Buckley, head of the archaeological team. Coogan, who plays Langley’s ex-husband John in the film, feels that it is generally accurate.

“The scenes are all manifestations of what actually happened,” Coogan says. “They might not be literal renditions of what happened, but the thrust of the film is absolutely true.”

The movie marks a reunion between Coogan, Pope and Frears, who directed the pair’s 2013 effort “Philomena.” The director, who has frequently helmed films and series based on real events, was compelled by the inherent strangeness of the events.

“I come from Leicester, so to me it was always comic,” Frears says. “It was always ridiculous that a king’s body should be found under a car park in Leicester. I’ve spent a lot of my life being told by women that they’re marginalized. And here was a story about a woman who had been marginalized and [we were] moving her into the center.”

Altering the timeline

In the film, Philippa Langley becomes interested in Richard III following a performance of Shakespeare’s play “Richard III.” She suffers from chronic fatigue syndrome and relates to him as a misunderstood figure. She begins to research his life, eventually joining the Richard III Society. She quickly becomes fixated on searching for the monarch’s remains, which she’s convinced are in a parking lot in Leicester.

The span of time between Langley’s fledgling interest in Richard and the discovery of his bones happens in what appears to be a matter of months. However, that was not the case. Langley’s actual search took nearly a decade.

“You have to condense time,” Coogan notes. “You don’t want to put in things like ‘A year later.’”

In reality, Langley first caught on to Richard III after reading Paul Murray Kendall’s biography of the king in 1993, and then saw a version of the Shakespeare play. She was captivated by the disconnect between the real Richard and the fictional stage version, presented as a villain. She spent years researching his life and later switched her focus to his death.

“When I was researching in Leicester, most people thought that the church where Richard had been buried was under a bank building and a road on a street called Greyfriars, or that he was in the river,” Langley recalls. “And there was one researcher in the Richard III Society, in 1975, who said that she felt that the church where Richard had been buried was located in one of three parking lots, but she didn’t footnote that material so I didn’t know why. It was when I started my research on the car park that it started to become viable.”

Langley made a request to the Leicester City Council to dig up the lot. Through the Richard III Society, she raised money for an archaeological dig via crowdfunding, and with the help of Buckley (played by Mark Addy), excavation began in the summer of 2012. A body, which Langley correctly believed to be Richard’s, was exhumed on the first day. However the rest of the team wanted to keep looking. The dig was extended an additional week by the university.

“It was eight years for me,” Langley recalls. “I understand it’s not a documentary, it’s a dramatization — a documentary would have been four hours long. They warned me that it was telescoped, it’s hit after hit after hit of the big things that happened. But I’m pleased with it because they picked the main moments and made them jell.”

She adds, “I think the story that you see is my story.”

More than a feeling

One of the most extraordinary aspects of Langley’s journey is that she discovered Richard in part thanks to the sensation she felt while standing in the parking lot. The first time Langley went to the lot, located behind a social services building, she got goosebumps. When she looked down, there was a “R” on the pavement.

“It was clearly for reserved parking,” she remembers. “But he was right there. Every time I went to that parking lot in that area, that hot-spot area in the northern end where he was, I would have this intuitive experience.”

Langley never told anyone about the feeling.

“I just knew instinctively that if I mentioned that, it would play against me,” she says. “As it was, they saw me as a bit of an oddity anyway, because I’m not a doctor. I’m not a professor. I’m not an archaeologist. And yet I was the one who was leading the search for Richard III.”

“She was a woman, and she was dismissed and marginalized and overlooked and kept out of the way,” Pope notes. “And she was someone who was in touch with their feelings. Richard III would still be in the ground if Philippa Langley hadn’t had that feeling.”

Imagining Richard III

Throughout the film, Langley has conversations with Richard himself (Harry Lloyd). Richard appears to Langley as the actor who played him in the Shakespeare performance earlier in the film. Initially, Coogan and Pope weren’t sure whether including him as a character was too much of a gimmick. But they kept coming back to it.

“We sort of led the witness to us,” Coogan admits. “We said, ‘Do you ever talk to him?’ She said, ‘Well, I did in my head.’ So that is artistic license — she wasn’t schizophrenic. She didn’t see him or have visions. It was a way of her figuring out her own thoughts as she looks for Richard and looks for herself.”

Langley, however, needed convincing.

“I’d been ridiculed and patronized and demeaned for being a woman who’s interested in a historical figure,” she says. “So ergo, you’re in love with him. I said to the screenwriters, ‘Look, you know, this is really concerning to me.’ But once I read it, I understood it and I got it.”

Credit where credit is due

As the film depicts, the University of Leicester was initially hesitant to get involved with Langley’s dig. Once the body was found, however, its academics stepped in.

“Once the dig started, that’s when things started to get a bit awkward because within the first couple of days of the dig starting we suddenly were realizing that ‘Yes, we are in the Greyfriars precinct area, and yes, the archaeology is looking very interesting,’” Langley says. “As soon as that happened, the university wanted to change what we were saying to the media.”

Following the exhumation of the skeleton, the university did genetic testing on the bones to see if it matched a mitochondrial DNA sequence discovered by historian John Ashdown-Hill. It was that match that ultimately confirmed that this was Richard. When the university announced the discovery, Langley was the 13th speaker on a list of 13. The university even plastered the words “We found him” on the sides of city buses.

“She didn’t have the resources to put that on the side of buses,” Coogan says. “What was interesting when the film came out [in the U.K.] was that certain people assumed that academics are beyond reproach. There was a closing of ranks of a certain class of people who did not like us challenging an academic institution, which we did. Really our film simply tries to redress that huge imbalance.”

Today, the parking lot where Richard was found has been transformed into the King Richard III Visitor Centre. Langley has continued her research. In 2016, she launched the Missing Princes Project to discover the true fates of Richard III’s nephews, King Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York.

“I can’t say too much, but later this year we’re going to be announcing the most exciting new discoveries that the project has found,” Langley confirms. “When Richard was found, a lot of [historians] were quite dismissive of it and saying, ‘Oh, it was luck.’ And then saying, ‘Well, it doesn’t matter anyway because we all know that he murdered the princes in the tower.’ And I’m saying, ‘No, actually, we don’t.’”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.