ULSAN, South Korea — Choi Byung-moon remembers that it was around 10 or 11 in the morning when the white minibus came under attack.

It was a clear spring day, and from the forested knoll where he stood, he watched the vehicle inch along a road running through a vast, golden field of barley before fellow commandos from the 11th Special Forces Brigade opened fire from both sides, bringing the bus to a halt.

He ran up the road to investigate. The windows of the bus had been blown out, and its sides, riddled with bullet holes, gave it the appearance of a honeycomb. Choi, a private first class, was the lowest-ranking member there, and the lieutenant in charge ordered him to board the bus and count the dead.

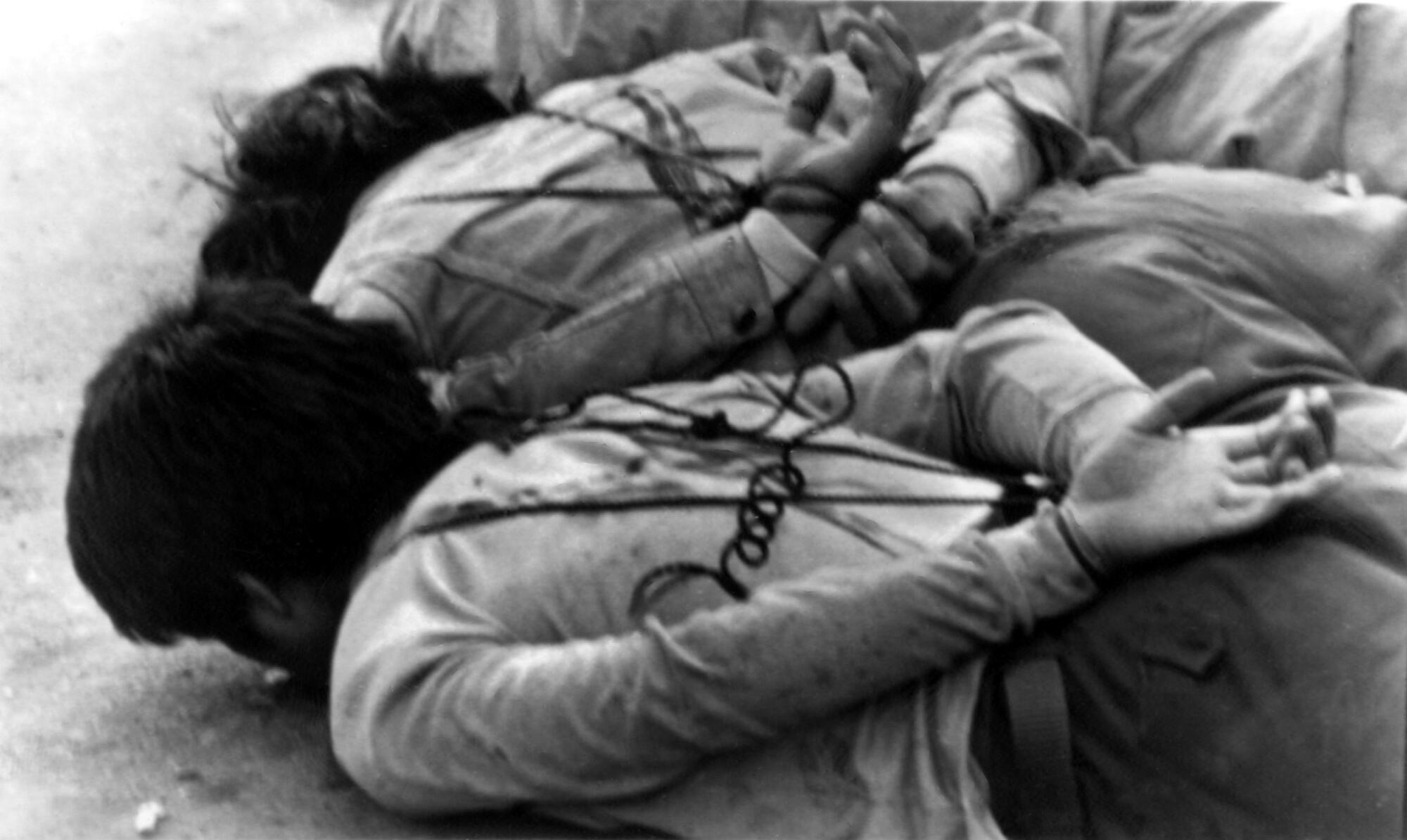

He tiptoed through the aisle, trying to not step on the bodies. There were 15, most tangled in twos and threes underneath the seats. The floor was slick with their blood. “That’s when I could tell that they’d been executed,” Choi recalled. “They were crawling underneath the seats trying to live.”

He was about to disembark when he caught sight of the girl. She had been pretending to be dead, quietly lying amid the bodies before finally staggering up. Startled, Choi almost shot her. She was about high school age and wearing a light-blue sweater. Her black hair was in a short bob, her forehead smeared with blood. Choi and the girl stared at each other, equally speechless.

“Were you shot?” Choi finally asked. The girl shook her head no. Supporting her by the armpits, Choi led her off the bus and called out: “One is alive!”

Spotting the girl, one of the noncommissioned officers snapped at Choi: “You son of a bitch, you should have just shot her. Why did you bring her out with you?”

The mood among the soldiers was tense and laced with a ruthlessness that seemed to bode ill for the girl and two other survivors — a pair of wounded young men who’d climbed out the windows.

Later, Choi asked around about what had become of all three. The men, both apparently members of the militia fighting the military, had been executed in the nearby mountains. Word was that the girl had been taken somewhere by helicopter. But with the officer’s menacing rebuke fresh in his ears, Choi figured that she had ended up dead too.

Though it would take 40 years before Choi realized it, this encounter would alter the course of his life. “Sometimes I feel resentful thinking about how I ended up in that unit and in that location on that day for my life to turn out like this,” he said. But in the winter of 2020, Choi would find himself on an unexpected path of atonement and confession that would lead him back to the girl — and force him to question the memories he had thought were as immutable as historical fact.

::

It was May 23, 1980, and the southwestern city of Gwangju was under siege.

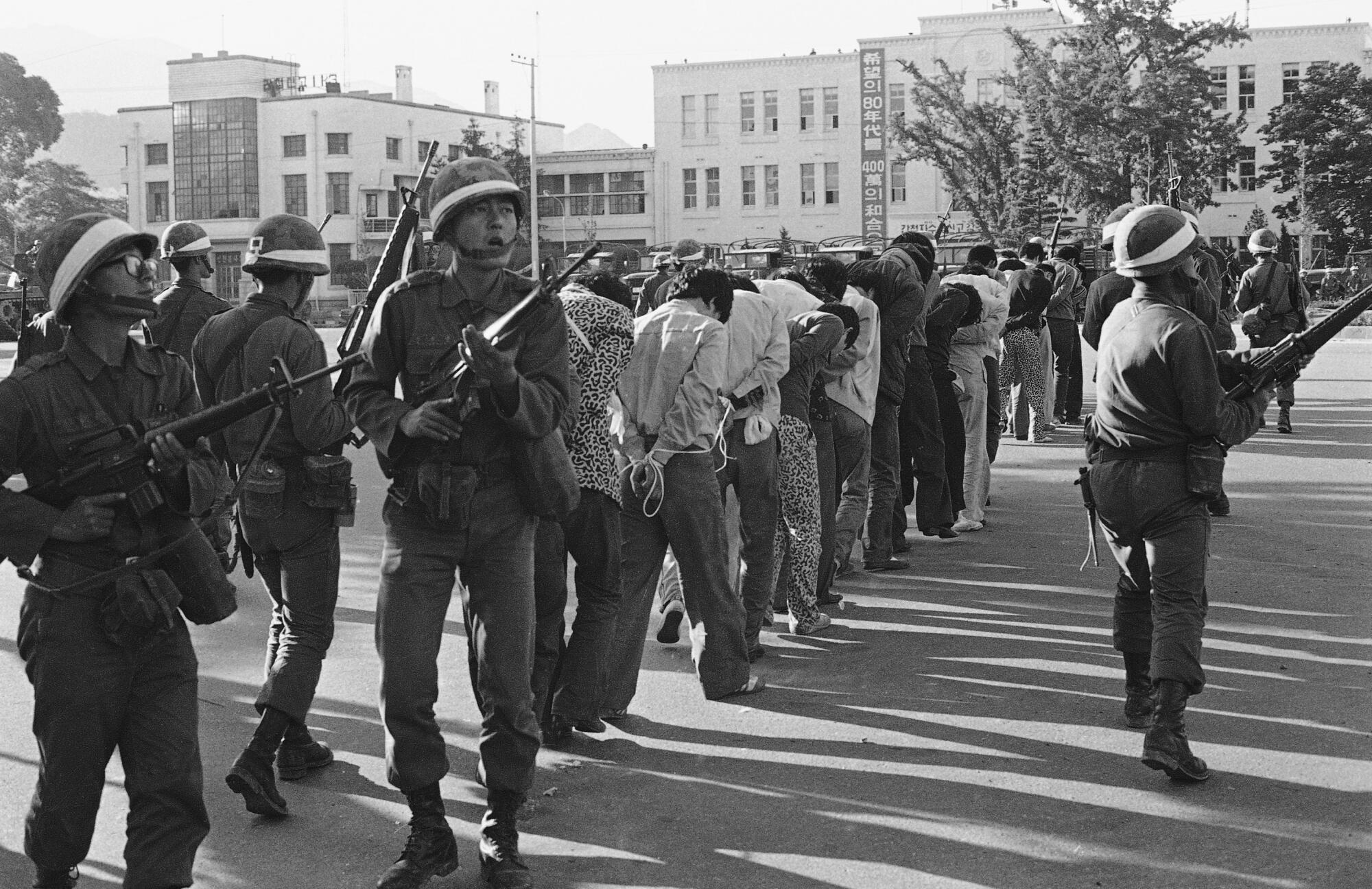

The Chun Doo-hwan military junta, which would go on to rule South Korea as a dictatorship for the next eight years, had just seized power in a coup d’etat and declared martial law. Branding the pro-democracy protesters filling the streets of Gwangju as violent insurrectionists, the junta sent about 3,000 elite paratroopers — among them a 21-year-old Choi Byung-moon — to crush the demonstrations.

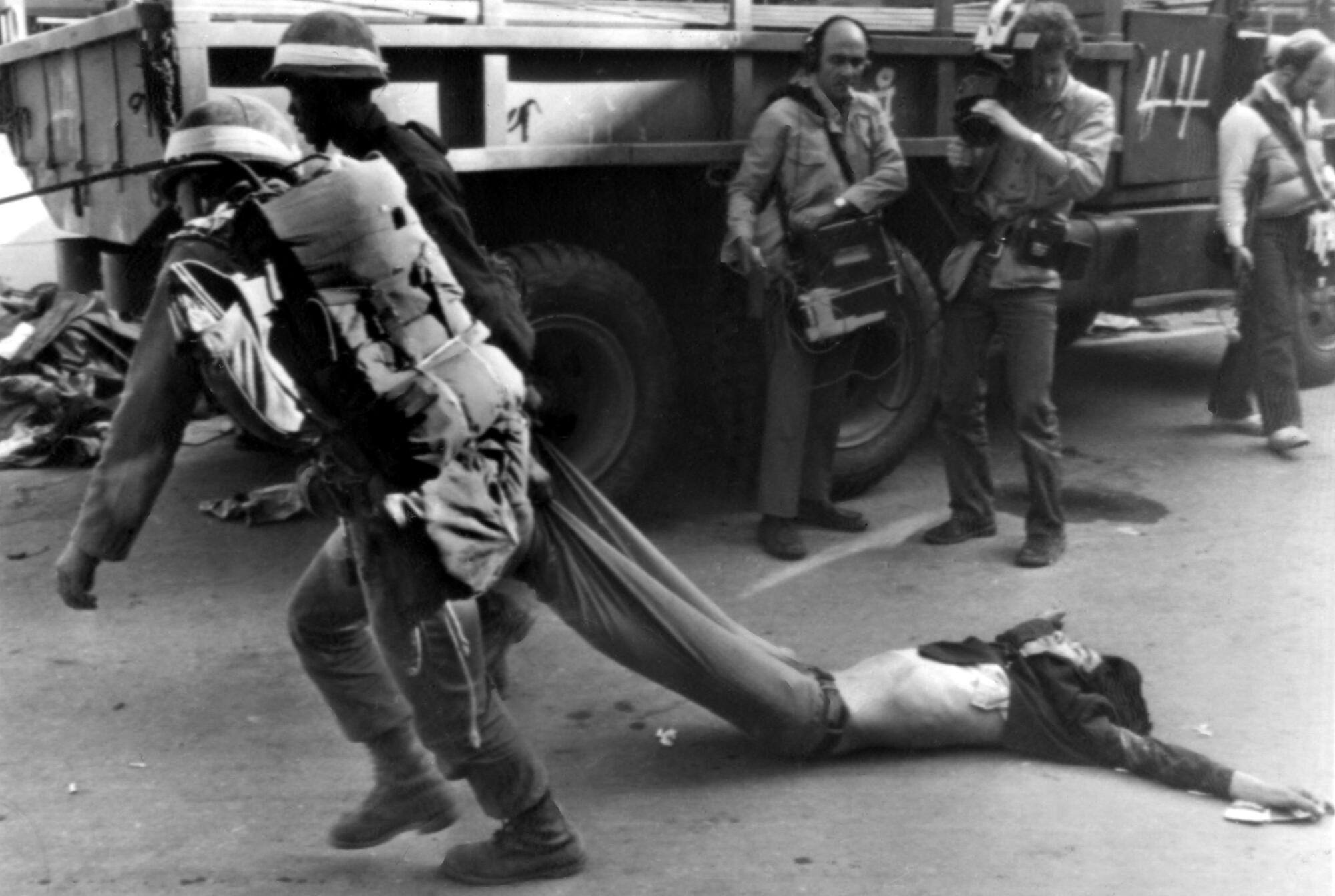

For 10 days straight, the commandos went on a campaign of terror, clubbing and shooting civilians with a bloodlust that one journalist on the scene described as “human hunting.” At least 165 people were killed.

South Korea’s first national reckoning with the atrocities committed during the Gwangju uprising was a series of televised parliamentary hearings in 1988 and 1989, the dawn of democratic rule.

Among the numerous witnesses was a young woman named Hong Geum-suk. Wearing a black blazer and a rigid frown, Hong testified that she had been a passenger on a minibus that had tried to drive past a military checkpoint before taking fire, and that 15 of the 18 passengers had died on the spot. She recalled that the only other survivors were two young men, and that they had been led away and executed. She had been taken by helicopter to an air base to be interrogated.

Choi hadn’t bothered to watch the hearing. After leaving the military in 1982, he had settled into the life of “just another ordinary young man,” dating, boozing and later starting his own construction firm. During the dictatorship, when the events in Gwangju were glorified as a necessary measure against a seditious mob, Choi believed he had simply done his duty. After the truth became public knowledge, he had painstakingly avoided watching or reading anything about Gwangju, hiding his past from even his wife and three children.

His awakening of conscience came in the early 1990s, when he happened to glance at a newspaper article about two boys who had gone missing during the uprising. Choi immediately recognized them as students from a nearby high school who had been trailing behind his unit as it marched through a dark mountain valley to Junam village, the site of the bus shooting, on the night of May 21. When apprehended, one of the students had tried to run and was shot, his body tossed into a creek. The other went missing.

Choi, now 64, said he hadn’t killed anyone in Gwangju. But after reading that article, he began to feel burdened by a deepening sense of complicity, both as a cog in a larger machine of killing and later as a silent witness. “During Chun’s regime we thought we were heroes,” he said recently. “But as the years went on I began to feel like maybe we had gone too far.”

He said he began to drink “365 days a year without fail” and developed a violent streak, getting into brawls over minor irritations. A tightness in his chest turned into episodes where his mind would suddenly go white. A cardiologist told him his heart was fine, but suggested he see a psychiatrist. When he finally did, he avoided mentioning Gwangju, chalking up his symptoms to life’s routine stresses.

Despite his efforts to forget, he found himself returning to the scene of bodies crumpled under the seats of the minibus, a snapshot of innocent civilians in their wretched last moments. Had he not, in some sense, led the young girl to her death? “It was a feeling of powerlessness at not having been able to do anything else,” he recalled. “Regret that my rank was so low.”

Choi wondered whether he would ever get the opportunity to publicly repent before he died. Then in late 2020, he received a call from a man explaining that he was with a group that was looking into the massacres in Gwangju.

::

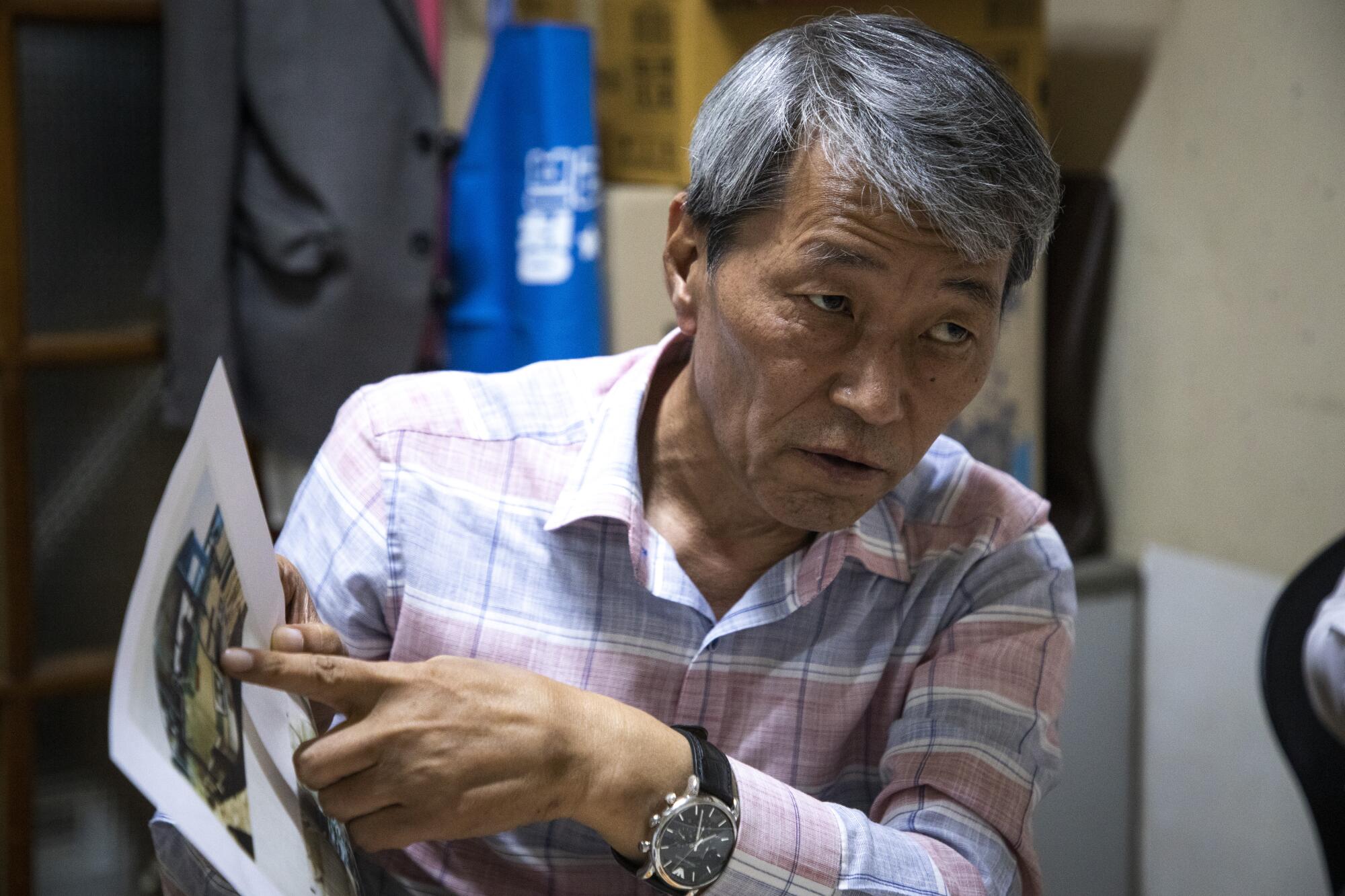

The man was a deputy of Huh Yun-sik, a senior investigator with the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission, a newly formed government inquiry into the atrocities in Gwangju.

Huh had been trying to track down Choi for weeks, making multiple five-hour drives from Seoul to Choi’s home in the industrial city of Ulsan, only to miss him each time. After several phone calls, Huh’s deputy finally managed to persuade a suspicious Choi to hear them out.

Seoul has fewer people living on the streets than Los Angeles. But tens of thousands live in illegal units so small there is barely enough space to lie down.

Huh, who is 59 and speaks with the distracted impatience of a beleaguered academic, leads the commission’s efforts to collect firsthand accounts from the 20,000 or so low-ranking soldiers deployed to Gwangju in May 1980. Previous inquiries focused on trying to extract confessions from senior junta officials — confessions that never came. “But we believed that the ordinary soldiers who actually carried out the operations on the scene — those who were acting on orders they had no choice but to follow — might be different,” Huh said.

The hope was that these previously unheard testimonies might unearth clues that could lead to the 78 bodies that were still missing, or help conclusively tie Chun Doo-hwan to the initial order to fire on civilians.

Underlying this project is the belief that confession can be its own reward for these former soldiers, a form of ritual unburdening as well as a chance for absolution, which has never been offered to them.

After the tumult of the 1980s, most of them, like Choi, quietly slipped into civilian identities. Now in their mid-60s, most of them lash out with anger when approached. The statute of limitations for crimes committed in Gwangju has long since passed, and the commission cannot legally compel anyone to testify.

“Ultimately, all we can do is persuade them,” Huh said. “But after 42 years, memories don’t come back easily. You really need to try to remember.”

::

On a frigid day in December 2020, Huh and his team met with Choi at a chicken restaurant in Incheon, a port city west of Seoul. Over shots of soju, Choi began to tell them, at first a little cautiously, what he’d seen in Gwangju, eventually turning the topic to an incident that sounded familiar to Huh. “He told us that he’d saved a young girl and handed her off, but that she had probably been taken to a military camp and executed,” recalled Huh. “He had believed this version of events his entire life.”

An astonished Huh realized that Choi was talking about the minibus shooting, which his team was investigating. Huh told Choi that the young girl he’d saved was alive — and that her name was Hong Geum-suk. “The moment he heard that he broke down in tears,” said Huh. “He was finally able to let go of the heavy weight that he had carried with him all this time, even a little bit.”

After that, Choi began to testify in earnest, persuading his former military friends to come forward too.

In April 2021, Kim Moo-sung, a documentary maker, approached Choi about a short film he hoped to make about this journey of confession. For the film’s denouement, Kim planned a dramatic reunion between Choi and Hong, hoping it would give him the closure he sought. Hong had accepted, and the commission agreed to arrange it.

The meeting took place late that month in Gwangju, by a gray stone cenotaph near the site of the minibus shooting. In Kim’s documentary, Hong appears around the bend and Choi stands up to take her in. She looks middle-aged, with a fleecy perm and wearing a gray hoodie underneath a black blazer. “You really were alive,” Choi says in disbelief.

One of Choi’s surest memories was the girl’s light-blue sweater, and he asks Hong whether she remembers her outfit that day. Hong says that she was wearing jeans and a checkered top. Taken aback, Choi repeats himself. “That’s not me,” Hong says firmly, waving her hands.

Other inconsistencies emerge as Choi and Hong sit down to match up their stories. Choi recalled the young girl telling him that she knew the two male survivors, but Hong says that they were strangers. Choi is certain that the shooting occurred in the morning, but Hong is adamant that it was the afternoon. The two eventually conclude, tensely, that there has been a mix-up.

Choi kneels before the cenotaph and hangs his head. “I realized then that the girl I’d saved must have been killed, so I just cried and cried,” he said. Hong, herself on the verge of collapsing, tearfully says to nobody in particular: “I wish it were really me.” Before she leaves, she hugs Choi tightly and consoles him: “Don’t hold this guilt in your heart, just put it all down.”

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Kim’s documentary ends here, as an anticlimactic story of mistaken identity. But it nonetheless seemed to touch on a sobering truth about the limits of the commission’s project: After 40-some years, it was entirely possible — even probable — that some questions might never be matched with satisfying answers, that the missing bodies might never be found, and that the closure and moral redemption that Choi was seeking, having become wishful abstractions, might not have anywhere to land.

::

After returning to his hotel room that night, a distraught Choi called up one of his old 11th Brigade friends with whom he’d recently reconnected. Desperate for answers, Choi asked whether he could remember anything else from the night of the minibus shooting. After some thought, the friend told him that Choi had mentioned the name of the school the girl said she attended: Songwon Girls Commercial High School.

Choi didn’t recall this piece of information. But the friend had been one of his closest confidants in Gwangju, and the two had spent many evenings recounting the day’s events to each other. It was possible that he had dredged up a crucial clue that Choi, in the blur of time, had somehow forgotten.

The next morning, Choi scoured the internet for anyone else from the minibus who might fit the bill. The name he eventually landed on was another young girl: Park Hyun-suk, a 16-year-old senior at the school his friend remembered. “Her name seemed familiar to me,” Choi said. “It was just this feeling like I’d heard it somewhere before.”

As it turned out, Park Hyun-suk had been one of the passengers killed in the minibus shooting that day, and she had been sitting next to Hong Geum-suk when it happened. Hong had recalled her by name in her 1989 testimony.

Choi called Huh, the commission investigator, to ask whether he knew anyone who might know more about Park’s case. Huh told Choi that she was survived by her older sister Hyun-ok, an acquaintance of his who currently ran an organization representing the Gwangju uprising’s bereaved. A meeting was arranged for that evening.

::

Choi arrived at Park Hyun-ok’s office wild-eyed and frantic, stumbling through a quick introduction before pelting her with questions.

He was desperate to confirm a number of details about Hyun-suk — details that had fallen flat with Hong the day before. Did Hyun-suk have a black bob? Did she know the two young men who were executed? And what had she been wearing at the time?

Over the years, Hyun-ok had meticulously pieced together a timeline of her sister’s last hours, which she now began to recount to Choi. Hyun-suk had, in fact, sported a black bob, and there were photographs to prove it. And she had boarded the bus that morning with their 12-year-old brother, who had gotten off before the attack. The brother had later said that Hyun-suk was secretly volunteering with the civilian militia and was taking the bus to go look for spare coffins outside the city. The young men with them, Hyun-suk had told him, were people she worked with.

After the bus shooting, Hyun-ok quit her job and wandered the city for months, searching for her younger sister until she received a tip that the Gwangju police station was displaying photographs of unclaimed bodies. Hyun-ok recognized her sister, whose body was badly decomposed, from an article of clothing: a light-blue “cardigan” that a friend had lent her.

Hearing this, Choi became certain that it was Park Hyun-suk — not Hong Geum-suk — whom he saved that day, only for her to be executed. He burst into tears. “To hear that the young girl I’d saved was killed,” he said. “The world came crashing down.”

::

In early 2022, Choi agreed to undergo forensic hypnosis at the South Korean army’s military police headquarters. He had lingering questions about the minibus shooting, and commission officials hoped that hypnosis might fill the gaps in his memory.

In the months leading up to it, Choi had drifted away from the theory that Park Hyun-suk had been the girl whom he saved and reverted back to Hong. He had been calling up old military friends who all confirmed that the incident had happened at 10 or 11 in the morning, squarely contradicting Hong’s insistence that it was the afternoon. In an April 2019 television interview that he had given before his death, his battalion commander had also named Hong Geum-suk as the girl from the bus.

These details had convinced him of the authenticity of his own memories, and that it was Hong who was mistaken. “I think she’s confused about some things,” Choi said. “I had a clear head at the time, but she’d just come back from the edge of death. She was completely disoriented.”

Though occasionally used in court, forensic hypnosis was no truth serum. Choi emerged from his four-hour session in a daze, recalling only the sensation of his memories lapping at the edge of consciousness but never quite breaking the surface. “We got a little more detail,” said Park Chin-un, the commission’s head of public affairs. “For example, regarding whether he held his rifle with his left or right hand, we learned that it was both hands.”

Small details like this hadn’t brought him any closer to a definitive answer. But Choi’s mind was elsewhere. “I felt an intense calm,” he said. “After it was over I felt relieved.”

::

Huh Yun-sik, the senior investigator with the truth commission, was largely unfazed by this outcome. Forensic hypnosis had its fact-finding uses, but its broader purpose was therapeutic. “When a subject really wants to remember something but they can’t and everything’s jumbled in their mind, it helps them organize everything narratively,” he said. “They say it eases the emotional weight they’ve been carrying all their lives.”

The commission, for its part, had concluded that the girl Choi met that day was Hong Geum-suk, whom they believe to be mistaken about several key details. Huh shared this opinion with them both, but Hong stood firm in her denial and refused to meet with Choi again. “We can’t undo the long process of Hong reinforcing her own memories at will,” Huh said.

Several weeks after the hypnosis session, Choi resigned himself to that fact. “The last few months have been very difficult,” he said. “I played out every possible scenario in my head.” But he said he was now certain — or as certain as one can be under the circumstances — that it had been Hong all along.

Even so, Choi had begun to wonder whether the same factors that rendered Hong an unreliable narrator existed equally for himself. Lurching from one short-lived jolt of certainty to the next had simply left him unsure about details that once seemed so vivid and firm. He had indeed seen a blue sweater, but did he remember it on the wrong girl?

There was also something liberating about this kind of self-doubt. It freed him from the need to resolve every last inconsistency, and Choi seemed at peace, distanced from the single-minded obsessiveness that had been its own kind of prison. “Just talking about it like this has been an immense source of comfort,” he said.

After suffering a diabetic stroke some time ago, he had begun to take his health seriously for the first time in his life. He hadn’t touched a drink in over a year and was no longer on medication. He had come clean about his experiences in Gwangju to his psychiatrist as well as his family and friends. He paid his respects to the dead, sought forgiveness at their graves.

Most of all, his testimony to the commission, which is due to publish what will be the first official account of the atrocities in June 2024, would be a small but crucial part of the historical truth that might allow others to begin to heal.

“I’ve been thinking of how fortunate it was that I ended up meeting the commission,” he said. “I think before, I’d lived with something like a knot in my heart.”

Still, he held out hope that Hong might agree to see him again someday. He was confident that she would come around. “I’d like to match up our memories one more time — to ask her to think again,” he said. “But I think it’s her. I’m almost certain.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.