The complicated — and dangerous — economics of Mexican fentanyl

For decades, Mexican cartels have made big money trafficking drugs. The trade was long dominated by hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine — but in recent years, the criminal organizations have taken over the underground fentanyl market, eclipsing China as the main U.S. supplier.

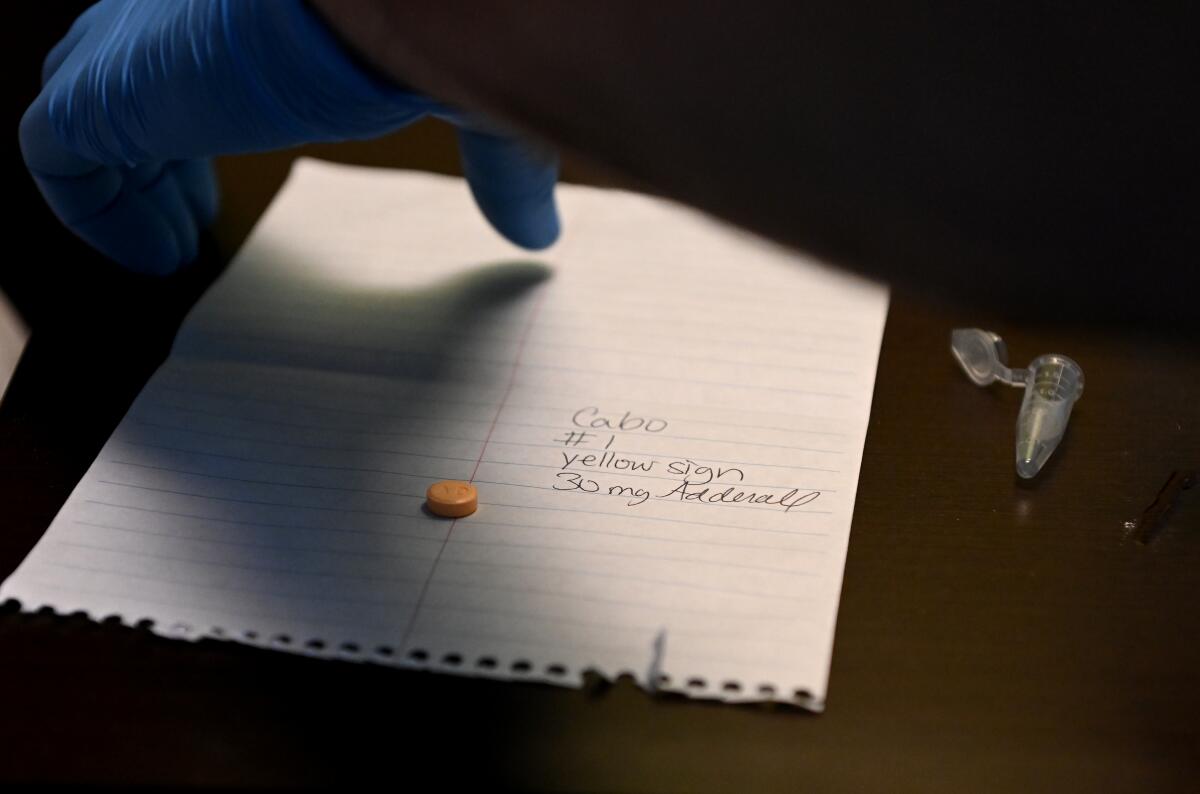

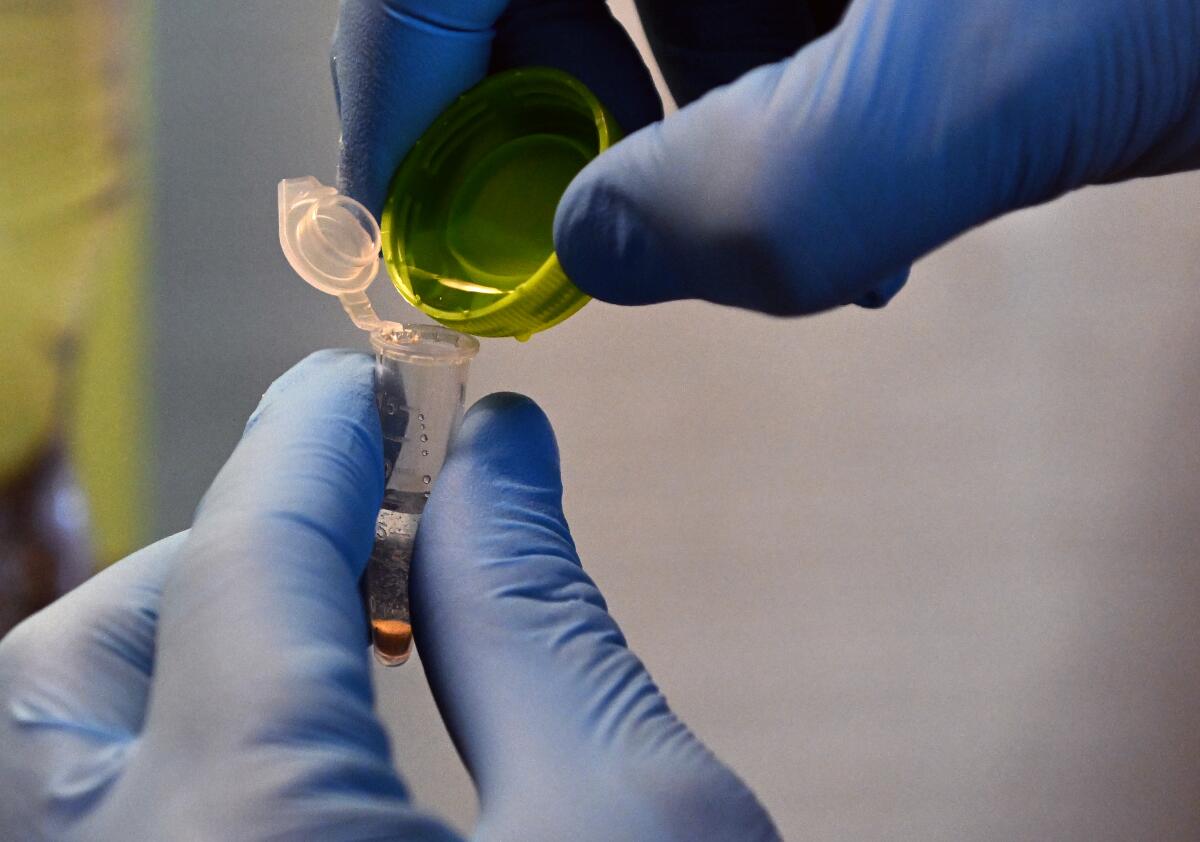

A Los Angeles Times investigation published Thursday exposed a new front in the cartels’ efforts to turn illicit fentanyl into cash. In three cities in northwestern Mexico, reporters found that some pharmacies are selling counterfeit pills laced with more powerful substances such as fentanyl and methamphetamine.

Experts said those pills are almost certainly coming from cartels aiming to pass them off as legitimate — and difficult-to-get — pharmaceuticals such as oxycodone and Adderall. But some readers wondered: Why would cartels go to the trouble of making fake pills, and lacing them with deadly drugs?

According to drug market experts, it all comes down to demand — and dollars.

“One of the reasons fentanyl has largely displaced heroin is because it’s easier to manufacture, you don’t need a poppy field, you just need a lab,” said Chelsea Shover, a UCLA researcher and the senior author of a recent study that paralleled the findings of the Times investigation. “You can buy a pill press online and make very convincing fakes.”

That explains why fake pills would make more business sense than heroin, but it still leaves the question as to why selling fake pills would be a more attractive business move than real pills.

Historically, legitimate oxycodone has been hard to come by in Mexico, especially outside of hospitals.

“For a long time it was difficult to get doctors to prescribe pain medications,” said Jaime Arredondo, the Canada research chair on substance use at the University of Victoria. “In 2015, they changed the law to make it a little easier in theory, but it seems like doctors are still relatively reluctant to prescribe.”

But even if prescribed oxycodone is difficult to come by, as Shover pointed out, “You don’t need a prescription to make a fentanyl fake.”

Aside from that, fentanyl is a relatively cheap and easy drug to synthesize, and a very small amount can go a long way.

“You can make a product of comparable strength using a lot less fentanyl than oxycodone,” Shover said. “You can make more pills with less product.”

And as Dr. David Goodman-Meza, a UCLA assistant professor who is also one of the study’s co-authors, said, it’s largely U.S. buyers who are driving the demand for these faux pharmaceuticals — not because they want the fakes, but because they’re looking for the real thing.

“This is especially true as we clamped down on access to pharmaceutical opioids in the U.S. in an attempt to ‘solve’ our drug use problem,” he said. “Selling fentanyl in the form of pills is really marketing to a group of the population that may not be willing to try ‘hard drugs.’”

Even someone who isn’t interested in heroin or cocaine might be willing to take a seemingly safe pharmaceutical pill.

At the pharmacies Times reporters visited last month, pills were generally priced between $15 and $35 each. Those figures are out of reach for many local drug users. And, as Arredondo explained, the market for oxycodone among Mexicans is not sizable — in part because physicians there have been so hesitant to prescribe powerful painkillers.

“It seems that it’s just filling a void for American tourists,” he said.

And catering to tourists is one way for cartels to expand their market.

“If you can get people who have more money addicted to fentanyl, even if they don’t know it’s fentanyl, they’re going to come back for more,” said Steffanie Strathdee, a distinguished professor of medicine at UC San Diego and another co-author of the UCLA-led study. “Tourists have more resources, and the cartels are aware of that.”

But exactly how much money counterfeit pills generate for cartels is more difficult to say, according to Romain Le Cour Grandmaison, senior expert with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

“One of the questions I’d like to be able to answer is how profitable is all that? How much does it really cost to produce it from A to Z? Because we hear so many different figures, the range of uncertainty in the figures is insane,” he said.

Unlike the cocaine trade, for which researchers have a strong sense of the economic model from the growing fields of South America to the streets of New York City, there’s very little reliable data on the economics of manufacturing, trafficking and selling fentanyl and fentanyl-laced tablets.

“We don’t know, like, how much does it cost to produce one pill?” Le Cour Grandmaison said. “With fentanyl, we don’t have the economic model at all.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.