CABO SAN LUCAS, Mexico — If you walk down the right side street, the offers are plentiful, even in broad daylight. Young men in plain T-shirts draw near and call out their wares: Pills. Cocaine. Guns.

But if you wave them away and go just a few feet farther, you can walk into a pharmacy where you might get something just as dangerous.

You just won’t know it.

A Los Angeles Times investigation has found that pharmacies in several northwestern Mexican cities are selling counterfeit prescription pills laced with stronger and deadlier drugs and passing them off as legitimate pharmaceuticals.

In Tijuana, reporters found that pills sold as oxycodone tested positive for fentanyl, while pills sold as Adderall tested positive for methamphetamine. Testing conducted farther south in Cabo San Lucas and nearby San José del Cabo bore similar results, although there, even weaker painkillers — including pills sold as hydrocodone — also tested positive for fentanyl. Many are nearly indistinguishable from their legitimate counterparts.

In total, the Times investigation found that 71% of the 17 pills tested came up positive for more powerful drugs.

A team led by UCLA researchers recorded similar results in a study last week, but this phenomenon has otherwise gone largely unnoticed. The new findings could represent a dangerous shift in the fentanyl crisis.

Until now, it was unclear that the powerful synthetic opioid had made its way into pharmacy supply chains. Even though Mexican drugstores are known for selling a wide range of medications over the counter — many of which require a prescription in the United States — experts generally believed those pills were at least what store owners said they were.

Now, that’s no longer a safe bet.

“Whenever you have counterfeit products that contain fentanyl, you are going to have people use them and die,” said Chelsea Shover, a UCLA researcher and the study’s senior author.

That’s because consumers — including U.S. tourists — who unknowingly buy these adulterated pills are at a higher risk of overdose when they ingest drugs far stronger than what they’re expecting. But how often that happens is impossible to tell.

Experts who study the effects of illicit drugs in Mexico say the country’s mortality data vastly undercount overdose deaths, which makes it difficult to understand the scope of the problem. While more than 91,000 people died of overdoses in the U.S. in 2020, Mexico reported just 1,700 fatalities that year from all drugs, including alcohol.

Fewer than two dozen of those, according to the data, were from opioids, compared with more than 68,000 opioid overdose deaths in the U.S. that year.

It’s unclear whether authorities in either country are aware of the problem. Carlos Briano, a spokesperson for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, said in a statement, “We refer you to Mexican authorities on this issue.”

The U.S. State Department and the White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy did not comment in response to detailed phone and email inquiries. Multiple local and national government agencies in Mexico also ignored requests for comment.

The synthetic drug is the leading culprit in the U.S. opioid epidemic. Most comes from Mexico, where traffickers have embraced it over heroin.

U.S. Rep. David Trone (D-Md.), who co-chaired the U.S. Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, called the findings of the Times investigation “extremely concerning” in a statement.

State Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz) described the findings as “really shocking.” Last year, he sponsored legislation that made it easier for California pharmacies to distribute any new opioid reversal agents as soon as they are federally approved.

“These places are close at hand, and Americans travel to these locations, and they are at risk in a way that wasn’t apparent before,” Laird said. “And I think that as this story comes out and we learn further details we’re going to have to look to see if there’s any state legislation that needs to be looked at to follow up.”

Fentanyl has been infiltrating the illicit drug supply for roughly a decade, since traffickers seized on the synthetic drug as a cheaper alternative to traditional opiates — and one with a higher profit margin.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has described fentanyl as up to 50 times stronger than heroin. A dose as small as 2 milligrams can be fatal. Unlike heroin, making it doesn’t require the space or expense of a sprawling poppy field — only a lab and the right chemicals.

When the drug first appeared on the street, it was often mixed into illicit powders. Then, it began appearing in counterfeit pills made to look like the real thing. Getting one of those pills still required a willingness to engage in illicit street deals.

But to many users, the faux pharmaceuticals seemed safer than drugs that required shooting or snorting. Accordingly, street pills found a much larger market than powders. If those pills can now be purchased in legitimate pharmacies, that market becomes larger still.

Were you or someone you know harmed by pills in Mexico?

We want to hear from readers about their experience. Let us know by filling out this brief form.

Of the 10 drug experts reporters interviewed for this story, all but one said they’d never heard of pharmacies selling counterfeit pills.

“I haven’t seen anything like that,” said Cecilia Farfán-Mendez, who studies cartels as head of research at UC San Diego’s Center of U.S.-Mexican Studies. “I think it speaks to the lack of law enforcement monitoring what’s happening in the pharmacies.”

Finding tainted pills in a Mexican pharmacy doesn’t take much doing: Pay a visit to a certain sparse shopping plaza near Tijuana’s red light district. Stroll past the picturesque stores and yacht-lined docks of Cabo San Lucas. Amble through a shopping district bustling with wealthy tourists in San José del Cabo.

In tourist districts in these three cities, there are signs for farmacias seemingly every few steps. It’s not rare to see two or three on the same block. The shops’ windows and whitewashed walls are often plastered with block lettering advertising a cornucopia of pharmaceuticals. Some have sandwich board signs on the sidewalk advertising pills.

Most of them display the bright-green cross familiar to anyone who’s tried to get a prescription filled in Europe. Much of this slapdash street advertising isn’t for the big chain pharmacies, but for the smaller ones — the independent and mom-and-pop shops.

One farmacia in San José del Cabo offered mini Buddha statues, incense burners and other tchotchkes alongside brightly lighted display cases of pill bottles neatly arranged on gleaming mirrored shelves. In Cabo San Lucas, one shop near a large dockside shopping mall featured a few racks of toys inches away from stacked boxes of medication. But in many stores, most of the tile floor space sits empty; there’s little pretense of selling other wares.

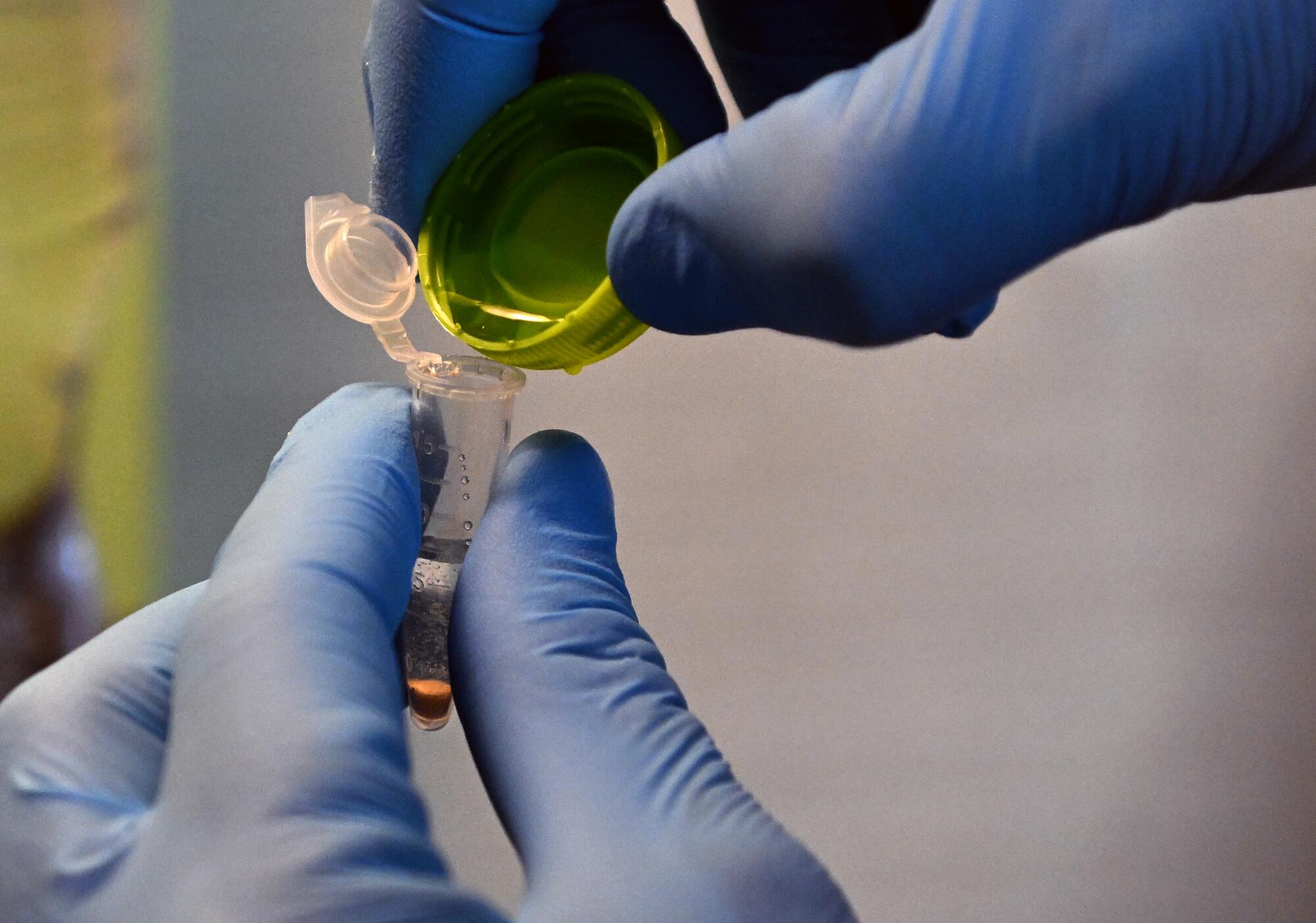

Twice in January, two Times reporters traveled to Mexico with testing strips to check more than a dozen pills for dangerous adulterants.

In farmacia after farmacia in Tijuana, Cabo San Lucas and San José del Cabo, they asked for Percocet and oxy and Adderall. They asked how strong the pills were. They said they planned to split the pills or use them to study or party or in some cases didn’t give a reason why they wanted the powerful drugs. None of the pharmacists inquired further.

Invariably, the tablets were kept in some hidden spot. Though bottles of less tightly controlled medications like Xanax or Viagra or Ultram were often on display in glass cases, more powerful and more closely regulated substances like oxycodone — whether real or fake — were secreted away.

The tablets cost $15 to $35 each, depending on the shop and the alleged potency. It’s a price point high enough to be out of range for many local drug users but within the reach of many tourists. Pharmacies such as these accept payment in most any format — credit card, pesos or dollars.

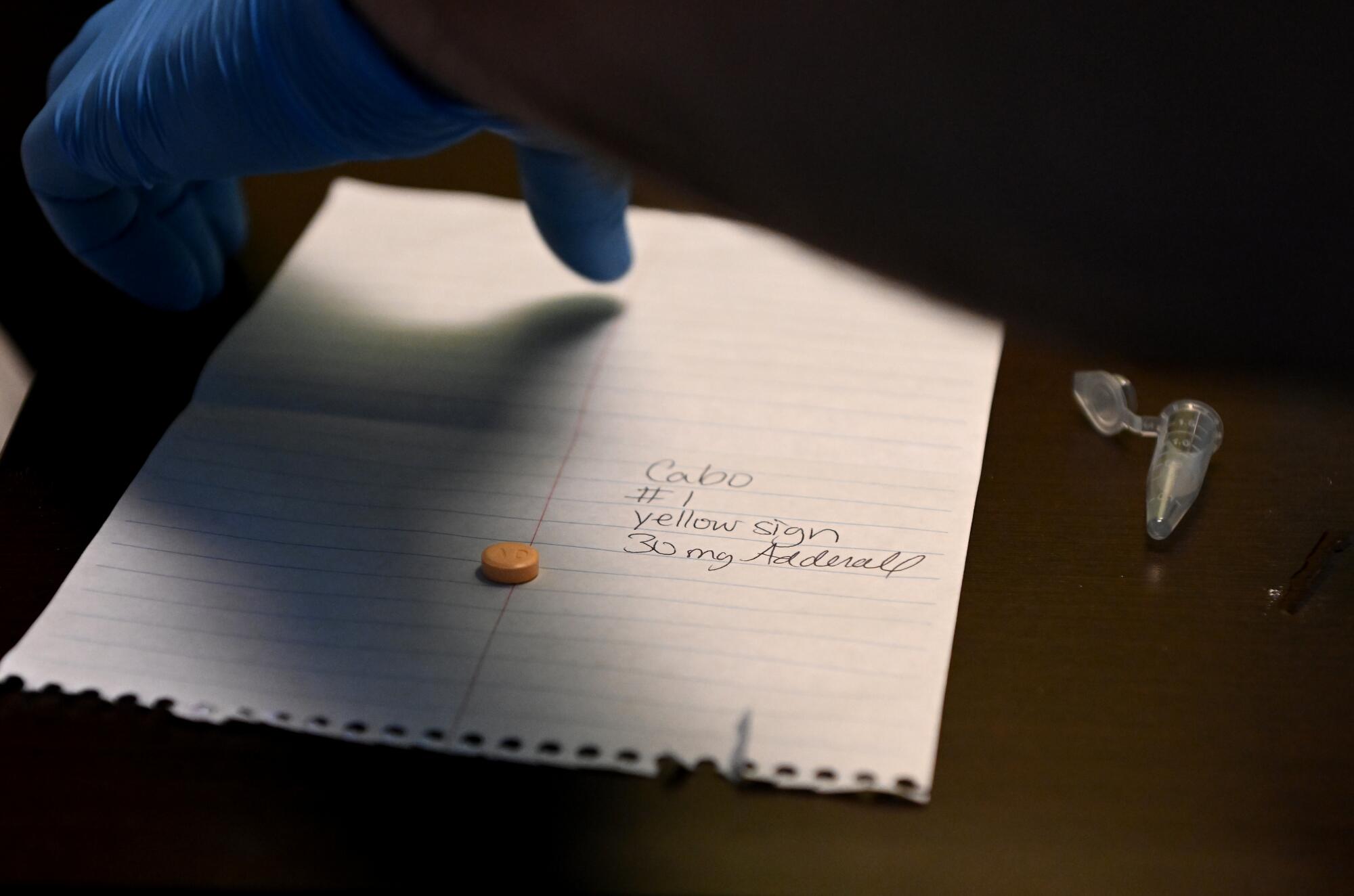

At one store in Tijuana, all the drugs turned out to be legitimate — or at least they did not contain fentanyl. At another, a $25 blue pill labeled M30 and sold as “Mexican oxycodone” tested positive for fentanyl, while a $25 blue pill labeled K9 and sold as “American oxycodone” did not. A single 30-mg Adderall — for $25 — came up positive for methamphetamine.

In Cabo San Lucas, where permissive pharmacies catering to tourists seemed even easier to find, nine samples from four drugstores tested positive for adulterants: Six came up for fentanyl, and three for methamphetamine.

Twenty miles away in the resort town of San José del Cabo, a blue oxycodone pill from one store tested positive for fentanyl, while a white one from another did not. Among the three cities, several stores declined to sell the pills individually, and two refused to sell them without a prescription.

The results parallel what the UCLA-led team found in four unnamed cities in northern Mexico. Though roughly a third of the 40 pharmacies targeted in the study would not sell high-powered prescription drugs over the counter, the majority did.

And of the 45 pills tested with an infrared spectrometer, researchers found that 20 were counterfeit, including 82% of the Adderall samples and 30% of the oxycodone samples. With their more precise equipment, the researchers were able to get more granular results — and to determine that three of the oxycodone samples were positive for heroin.

They, like The Times, also found that all of the counterfeit pills came from stores in areas frequented by tourists, in locations that often featured English-language medication advertisements.

But the team’s work is a preliminary study — a pre-print that has not been peer-reviewed — and Shover said there are several important unknowns.

“We don’t know exactly when this started, and we don’t know how widespread it is,” she said. “We don’t know who’s buying these pills, we don’t know who’s taking them, and we don’t know what’s happening to the people who take them. The most important unknown is probably how many people have died or had serious health consequences from it, and we don’t have any idea.”

Mexican death data are notoriously imprecise. Experts who study drug deaths say that’s partly the result of a long wave of drug-related killings that have overwhelmed the country’s forensic services and made thorough testing nearly impossible.

When somebody dies in Mexico, a physician can note the suspected cause on a death certificate, but that’s only if there’s a physician involved, said Dr. David Goodman-Meza, an assistant professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and one of the study’s co-authors.

If there’s no death certificate, then the country’s forensic medical service, known as SEMEFO, handles the investigation.

“However, SEMEFO is super-backlogged,” Goodman-Meza said. “The homicide numbers are incredibly high, so those likely get priority. And that means they’re not digging deep on other deaths or doing advanced toxicology to know if drugs were involved.”

Instead, overdose deaths get chalked up to broader, catchall causes.

“The default when you don’t have an explanation is to say that the person died of a cardiopulmonary arrest,” he continued. “But, I mean, we all die because our hearts stop.”

In 2020, the Mexican government attributed just 19 deaths to opioid use. The U.S. State Department, meanwhile, noted two drug-related deaths of Americans in Mexico that year.

Those figures are “probably very low,” said Romain Le Cour Grandmaison, senior expert with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. “I would imagine it’s a lot more, but it’s impossible to say how many.”

It’s also often impossible to know where a specific laced pill came from, but, according to a bipartisan congressional report issued last year, Mexican drug cartels are the ultimate source for many of them.

Cartels first bet big on fentanyl in the 2010s, importing the drug straight from China to mix into the powdered heroin most prevalent in East Coast drug circles. As recently as four years ago, Chinese-made fentanyl still dominated America’s illicit supply, according to the congressional report.

But cartels knew they could make more money by producing it themselves. So they began importing precursor chemicals, setting up clandestine labs and flooding the market with Mexican-made fentanyl, according to Fernando Montero Castrillo, who researches opioid markets at Columbia University’s HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies.

In the years that followed, the amount of fentanyl seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection more than tripled, from 4,800 pounds in 2020 to 14,700 pounds last year.

“Pretty much all the fentanyl that comes into the United States comes from Mexico now,” Castrillo said. “Very little comes in from China.”

Though federal and local authorities in Mexico did not respond to requests for comment, the Mexican government has previously said it is working to stem the flow of chemicals used to produce fentanyl.

Cartels are almost certainly the source of the counterfeit pills appearing in drugstores, said Farfán-Mendez.

But pharmacy owners are most likely not buying directly from the criminal organizations. There are typically networks of middlemen, she said, so it’s unclear how many pharmacists even know they are selling laced pills.

When reporters visited last month, at least a few drugstore workers seemed aware their over-the-counter offerings were unusually potent.

“This one’s very strong,” cautioned a man working one afternoon behind the counter at a pharmacy less than half a mile from the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana. He was differentiating between two pills he presented when asked for oxycodone: the one he pointed out, which later tested positive for fentanyl, and one that came up negative.

The fact that reporters and researchers were so easily able to find drugstores selling fentanyl-laced tablets in multiple Mexican cities “signals that [customers] go into these pharmacies looking for counterfeit oxys,” said Farfán-Mendez. “So I can see the incentive to supply it.”

But cartels could be moved to reconsider that approach “if we start seeing a number of deaths in a certain area, especially if they are American tourists” and police crack down on the practice.

Given the shortcomings in Mexican death data, spotting those deaths could be difficult — which means cartels will have little reason to curb their pill trade.

“If it’s profitable and there’s not a lot of enforcement,” she said, “they’re going to keep doing it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.