Why California’s great outdoors isn’t real to me until it might kill me

Editor’s note: The Wild is all about featuring a variety of exciting voices from Southern California’s outdoors scene. For the next several weeks, we’re featuring guest writers (whom we’ve dubbed “wilders” ) from around The Times who are eager to share their adventures with you. This week’s guest wilder is Kim Janssen, senior director of long-term planning, who lives in Altadena and believes motorcycles are the solution to most of L.A.’s problems.

When you look at a California landscape, what do you see?

A mountain, a desert, an ocean, a forest, or something stranger?

It depends not only on what you’re looking at but what you’re looking for.

I came seeking the memory of E.T., a boy flying on a BMX, silhouetted against a Tujunga moon; the Bones Brigade, bombing an O.C. drainage ditch; and a bleached Looney Tunes desert where the only thing more certain than violent death was near-instantaneous resurrection.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Bathed in what I only later learned was L.A. light, these images were beamed down the 1980s culture hose into my rainy London childhood, so that adventure, magic and the way California looks on film were irrevocably intertwined in my mind from an early age.

It now seems inevitable that I would eventually be drawn here, in my 40s, to a place that looks like the landscape of my childhood imagination.

“Just like a cartoon!,” is how my wife, Becky, who grew up in Bogotá, Colombia; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Miami, puts it. It’s her highest compliment to say that a rock or a squirrel or a cactus “looks like a cartoon,” meaning that the rock or the squirrel or the cactus does not seem weighed down by reality but has achieved its platonic ideal state, as if drawn by Tex Avery or Walt Disney, as we first saw them.

We immigrants carry these images deep in our visual grammar; the way so many of us perceived the world was Californian, long before we got here. And so our understanding of California, even after we arrive, and especially of the wilderness, can be heavily mediated and often unrealistically benign.

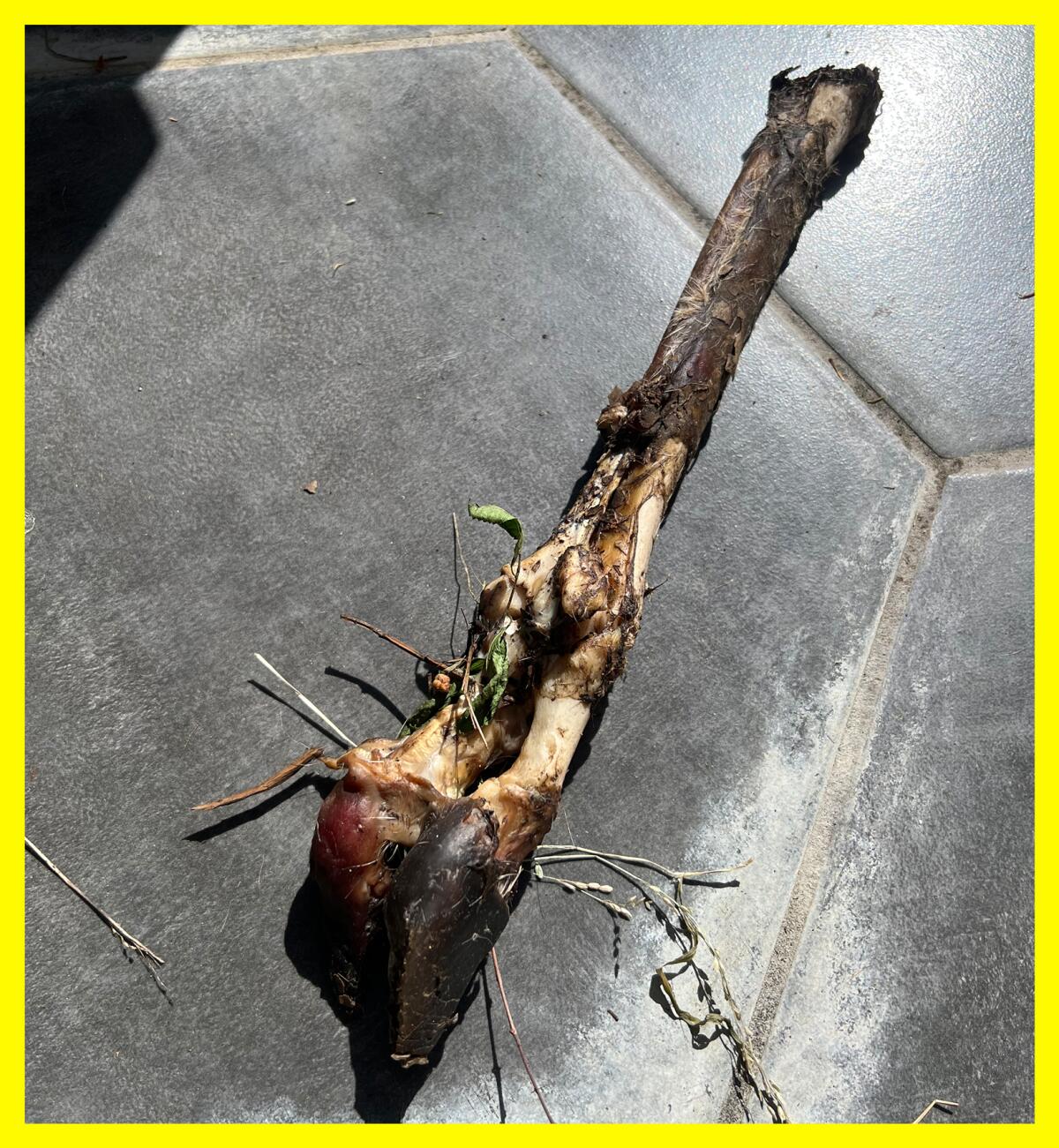

How else to explain that when my wife and I first saw our Altadena home, at an open house, and a neighbor came out into the cul-de-sac to warn us that a bear in pursuit of a handful of cold McDonald’s French fries had, just a couple of weeks earlier, walked off the side of the mountain and destroyed her car, we regarded it as a selling point?

Or that when a 400-pound black bear, perhaps the same one — let’s call him Yogi — wandered onto our deck one afternoon this summer, five feet from my wife and me, separated by only 3/32 of an inch of extremely breakable patio door glass, my first instinct was not to make myself large, to get noisy or to grab the bear spray from on top of the fridge, but to hold up my iPhone and shove my wife between me and the bear in order to snap a killer holiday card photo.

As much as I’d like to blame William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, there’s something more primal at work, I suspect, in the magical thinking that requires some of us — middle-aged men in particular — to inject mortal risk into our communion with nature.

A simple sunset can still move me, but it can be hard to escape the feeling that it’s only beautiful to me insofar as it looks like the poster art from Bruce Brown’s “The Endless Summer,” or the logo on a pair of faded Ocean Pacific board shorts. It’s trite, too easily had.

The California that exists outside the movies is not easily spiritually accessible to me, even when I’m in the most remote, unspoiled corners of the state.

Instead, like all of the most valuable experiences, it has to be earned.

I have friends who find it in weeklong silent retreats, or in the sustained practice of yoga. But I find it easier to relate to the older men who died hiking across Death Valley during a heat wave, or trekking up Mt. Baldy in a blizzard.

For me, it happens at 70 mph, on my dirt bike.

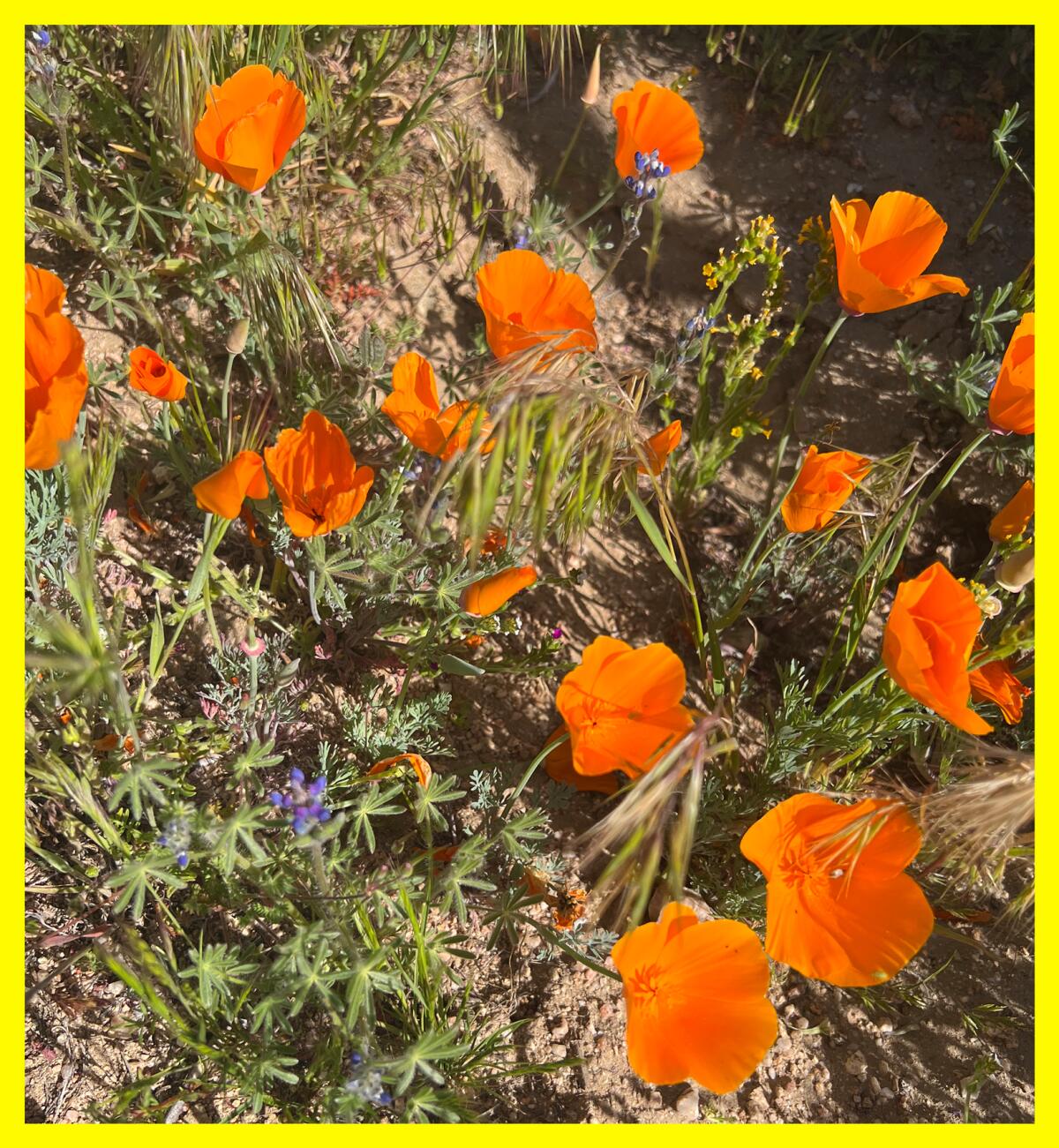

At 70 mph on a dirt bike in the Mojave Desert, a cactus is not a prop in a Wile E. Coyote pratfall but a very real, solid and spiky obstacle you absolutely do not want to hit.

Sagebrush, citrus blossom and desert lavender are not tasteful hand-soap scents but bright, vivid colors in your nostrils.

That exposed cliff at the edge of the trail is not something you are going to run off, keep running in midair, look down, look at the camera, gulp and fall from, only to be magically restored seconds later.

It is an actual cliff. You will die if you ride your motorcycle off it.

It’s at the point where the phrase “being humbled by nature” takes a more prosaic meaning that reality asserts itself, and that the dreams of youth collide with an immovable part of the Mojave to remind you that you are not, in fact, the reincarnation of Steve McQueen but a middle-aged man whose lust for speed exceeds the limits of his talent.

And it’s at the point just before that, when I’m on the ragged edge, deep in concentration, in a state of pure, childlike flow, power-sliding through corners, popping jumps off bumps in the trail, daring myself to twist the throttle harder and brake later, that my mind clears and I can achieve a fleeting moment of Zen, when the Mojave is not the backdrop to “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” or “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” but just the Mojave sand, rushing past, 12 inches below my feet.

Whatever you’re seeking, whether it’s a Hollywood sunset, a bear that might eat you or simply a fleeting moment of peace, I hope you go in search of it in the California wild this week.

3 things to do

1. Dig showbiz dirt on a walking tour of the Hollywood Forever Cemetery. The Art Deco Society of Los Angeles leads a walking tour of the famous, 124-year-old cemetery, on Oct. 15, with tours starting every 20 minutes from 9 to 11 a.m.

Expect to hear about the accomplishments and misdeeds of Hollywood greats including Cecil B. DeMille, Rudolph Valentino and Hattie McDaniel at their memorials during the 2½- to 3-hour walk. Tickets are $30 at the door, $28 in advance (Art Deco Society members get a $10 discount). More information and a link to purchase tickets (advance sales end at 11:59 p.m. Oct. 14) can be found at artdecola.org.

2. Take a gay camping trip in Anza Borrego. Gay Camping Friends — a group formed during the pandemic for folks who wanted an outdoorsy alternative safe space to gay bars — teams up with California Gay Adventures to host a three-night camping trip with 4x4 runs, hikes and group meals from Oct. 19-22 at the Borrego Palm Canyon Campground.

You may still be able to grab a spot at one of the four sites the group has booked by signing up, or you can organize your own spot at an adjacent site or nearby hotel. Find more details at the Off-Road Gays @ Anza Borrego event page on Facebook.com.

3. That morning walk? Put a bird on it. The L.A. Audubon Society puts on regular birdwatching walks around L.A. as well as longer, out-of-town trips.

On the third Saturday of each month, it’s a morning walk at the Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area that takes in landscaped parkland, an artificial creek and lake and natural and restored areas of coastal sage scrub habitats within the Baldwin Hills.

Expect to see resident birds such as the black phoebe, Cassin’s kingbird, California and spotted towhee, song sparrow and red-tailed, red-shoulder and Cooper’s hawks. Binoculars are provided and parking at 4100 S. La Cienega Blvd. costs $6. No advance signup is required. laaudubon.org

The must-read

Environmentalists hate plug-in hybrid cars, viewing them as “fake electric” vehicles that don’t do enough to combat climate change, my colleague Russ Mitchell writes in this subscriber exclusive story.

Count me as a fan, and someone who was frustrated I couldn’t buy a midsize plug-in truck when recently shopping for a family vehicle.

Electric cars are great in the city, if you can charge at home, and they are workable for longer trips on more established routes where there is charging infrastructure.

But for those of us who regularly go deep into the less populated parts of the state — as I do, to ride and race dirtbikes, or to camp — pure electric vehicles are not nearly so practical.

Yes, there are electric trucks. My pal has a California-designed Rivian, which is a phenomenal vehicle, but they’re extremely expensive and he experiences range anxiety whenever we are out in the boondocks, far from chargers.

Widespread problems with the charging network, especially in out-of-the-way spots, caused another of my colleagues, Mariel Garza, to consider trading in her electric Kia earlier this year.

A plug-in, which typically has an electric range of 25 to 45 miles, would allow me to drive purely electrically for most of the week in L.A., relying on gas, without range anxiety, when I head into the wilderness on the weekend. But nobody sells a midsize plug-in hybrid truck in the U.S., so I bought a gas-guzzling Chevy.

Environmentalists do themselves few favors with rural motorists, or those of us who don’t have a practical pure electric solution to their car needs, when they condescend to folks who’d like to be part of the solution.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Like hundreds of thousands of Californians, my family lives in a high-risk fire area, where the private insurance market will not cover homes against fire risk, and we depend on the state’s FAIR plan.

So my head was on a swivel when I experienced my first local wildfire this summer — just a few hundred yards from my house.

Thankfully, the firefighters did a great job at putting the blaze down within an hour, before it spread more than a few acres. I personally went and thanked them.

The stress of the fire was ameliorated, somewhat, by an app my neighbor recommended, Watch Duty, which provides real-time fire information faster than anything else I’ve seen or used.

A group of 60 volunteers across the Western U.S. maintains the app, using scanner traffic, crowdsourced photos and other information, often posting alerts before the authorities. It’s not a foolproof solution — nothing is — but if you live in or spend time in fire country, consider downloading it.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.