Walk in Abraham Lincoln’s footsteps 150 years later at preserved sites

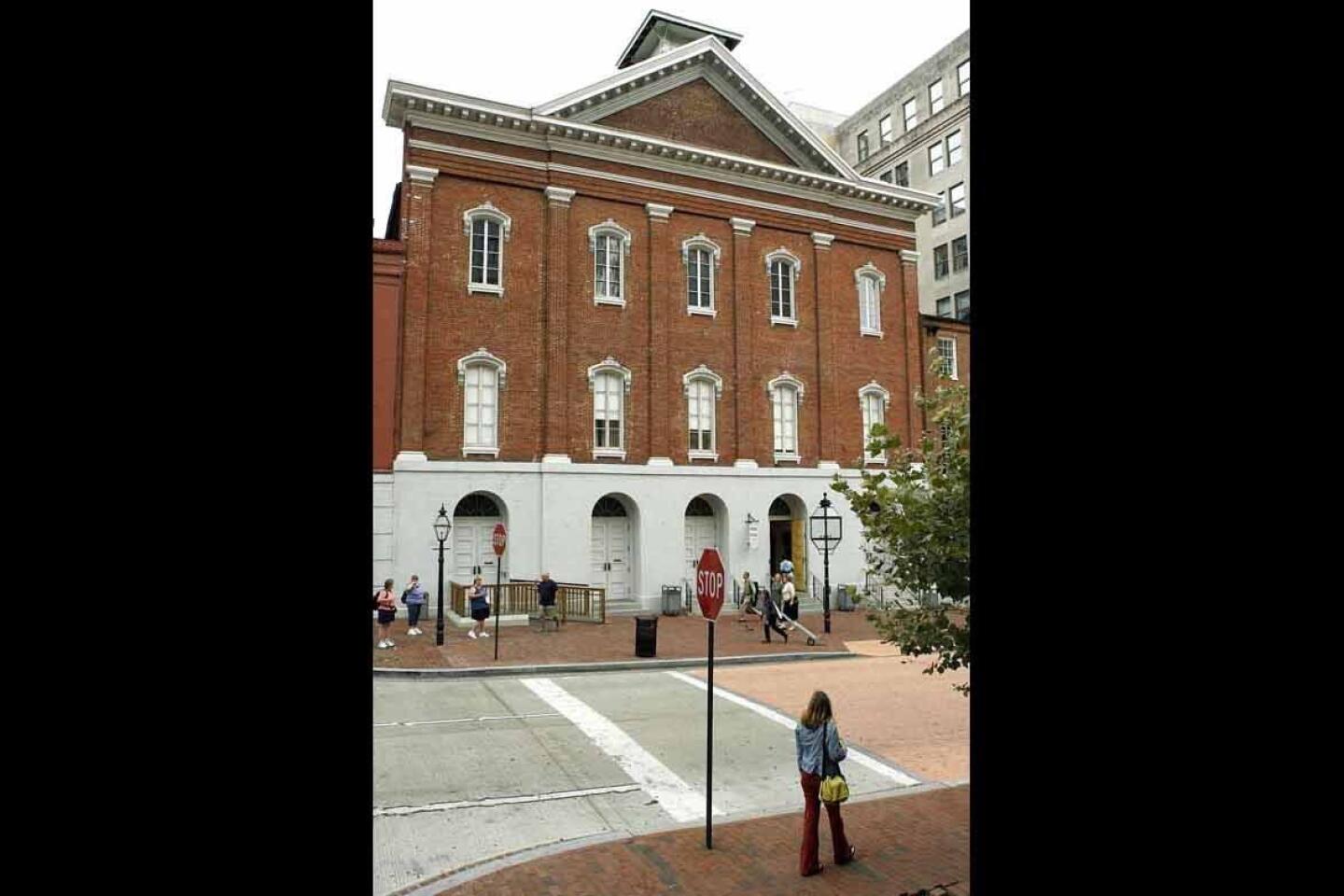

WASHINGTON, D.C. — There’s nothing quite like wandering around the spot where a historic event occurred to help the imagination grasp how it all unfolded. Which is why I was standing on one side of the wraparound balcony in Washington, D.C.’s Ford’s Theatre last year, gazing across to the presidential box where John Wilkes Booth shot Abraham Lincoln before leaping to the stage and freedom.

No wonder Booth broke his leg, I thought. That’s quite a drop.

It wasn’t exactly revelatory, but being able to walk around the theater where that tragic shooting occurred 150 years ago, on April 14, 1865, put those few moments on a human scale and helped make the abstract concrete. As did walking across the street to the Petersen House, where the bleeding and unconscious Lincoln was carried shortly after he was shot, and where he died the next morning.

GUIDE: Your travel guide to commemorating Abraham Lincoln’s monumental life

Lincoln buffs have a range of preserved sites where they can touch the same places that Lincoln did, from his roots in Kentucky to Washington to the Illinois cemetery that holds his body. That so many of those sites have been preserved speaks to Lincoln’s enduring appeal as not only the president who ultimately kept the states united, but as the first of the four U.S. presidents to be assassinated (James Garfield, William McKinley and John F. Kennedy would follow).

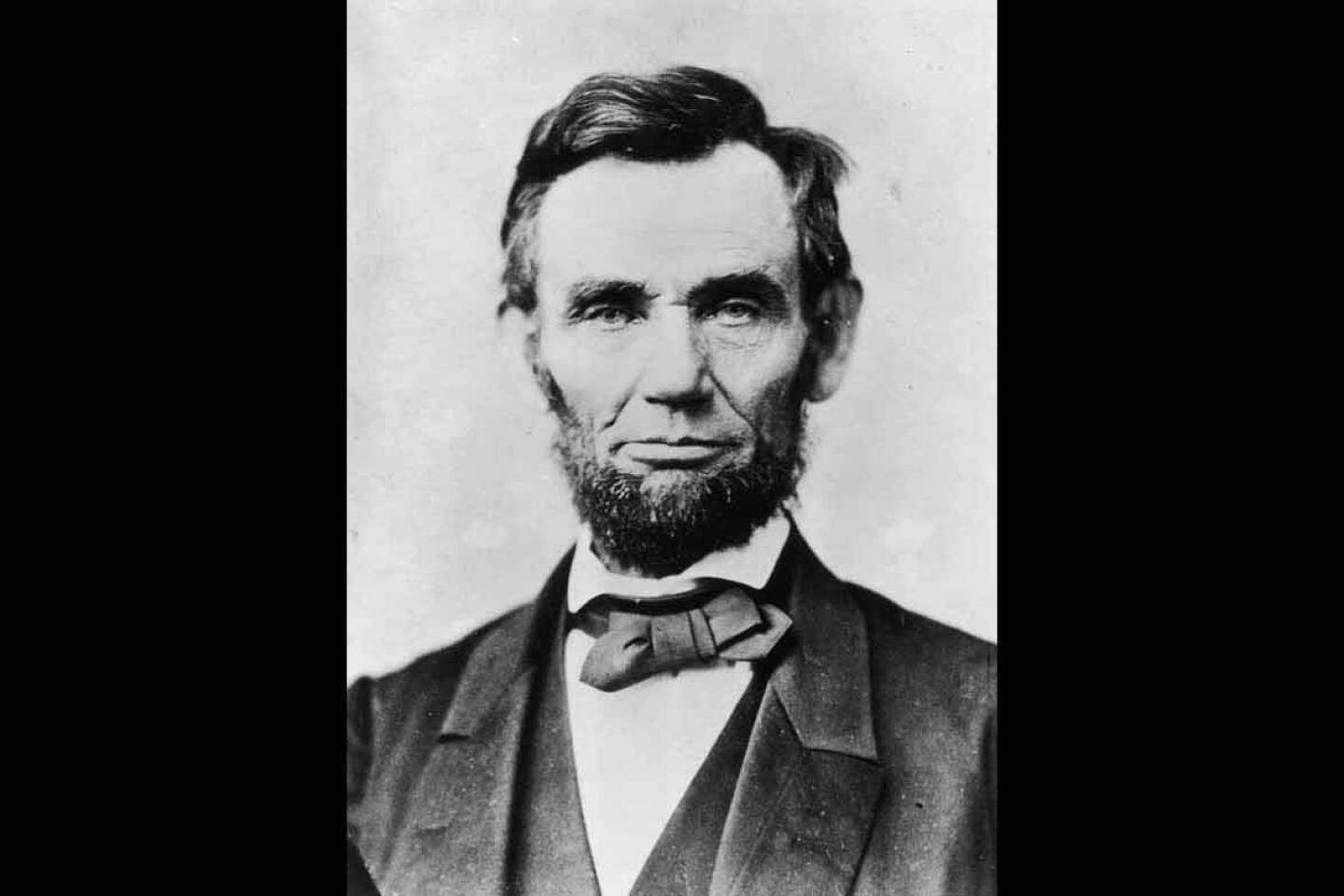

But the hagiography surrounding “Honest Abe” also appeals to our sense of what we perceive the nation to be. The overview we all receive as school kids renders him heroic — the Great Emancipator who freed the slaves.

A deeper reading of those tumultuous, bloody days reveals a more nuanced Lincoln, a man open to interpretation. To some, he was a racist who nonetheless believed in the Constitution’s guarantee of rights for all. To others, he was a martyr for freedom and for the country.

Although Northerners credit Lincoln with making the riven country whole, Southern revisionists blame him for the “War of Northern Aggression” and the destruction of the South (never mind that the Confederacy fired the first shots as the states dropped out of the union in the wake of Lincoln’s 1860 election). Booth himself accused Lincoln of tyranny.

And on it goes, each version supported by a small library of research and argument.

Then there’s the publishing legacy. It’s hard to get an accurate count, but some estimates tally more than 16,000 books about Lincoln, more than any other person except Jesus Christ. The Library of Congress’ online catalog lists more than 6,900 books with Lincoln as the subject, compared with more than 2,600 for Kennedy.

The scope of the output makes for an impressive stack. A 34-foot-tall spiral of 6,800 Lincoln books rises inside a staircase at the Ford’s Theatre Center for Education and Leadership (an intimidating sight for someone who was then writing about the guy who killed the guy who killed Lincoln; was there room for another book?).

Of course, there was more to Lincoln’s life than the presidential years, which Lincoln enthusiasts can follow through their own travels. The trail starts at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace, site of the legendary log cabin in Hodgenville, Ky. (In an unfortunate bit of timing, part of the park is closed for a construction project.) When Lincoln was 7, the family relocated to what is now Lincoln City, Ind., near the Ohio River, where you will find the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

Lincoln’s legal and political career took root in Illinois, and Springfield is a go-to spot with the Lincoln Home National Historic Site, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum and the Lincoln Tomb, from which grave robbers tried to steal the body in 1876, leading cemetery caretakers to temporarily hide it elsewhere on the grounds.

But the Washington area reigns supreme for those pursuing Lincoln history. There’s the white Gothic revival Lincoln Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home, where Lincoln lived for some of the war years, and the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, where the Lincoln family attended services.

Aficionados can sign up for tours that follow the path Booth and co-conspirator David Herold took as they fled Washington for what they hoped would be sanctuary in the Deep South. They made it as far as a tobacco barn near Port Royal, Va., where Herold was captured and Booth shot by Sgt. Boston Corbett, a member of the 16th New York Cavalry. Among the tour stops is the Maryland tavern where Booth and Herold picked up some cached supplies, a place now preserved as the Surratt House Museum.

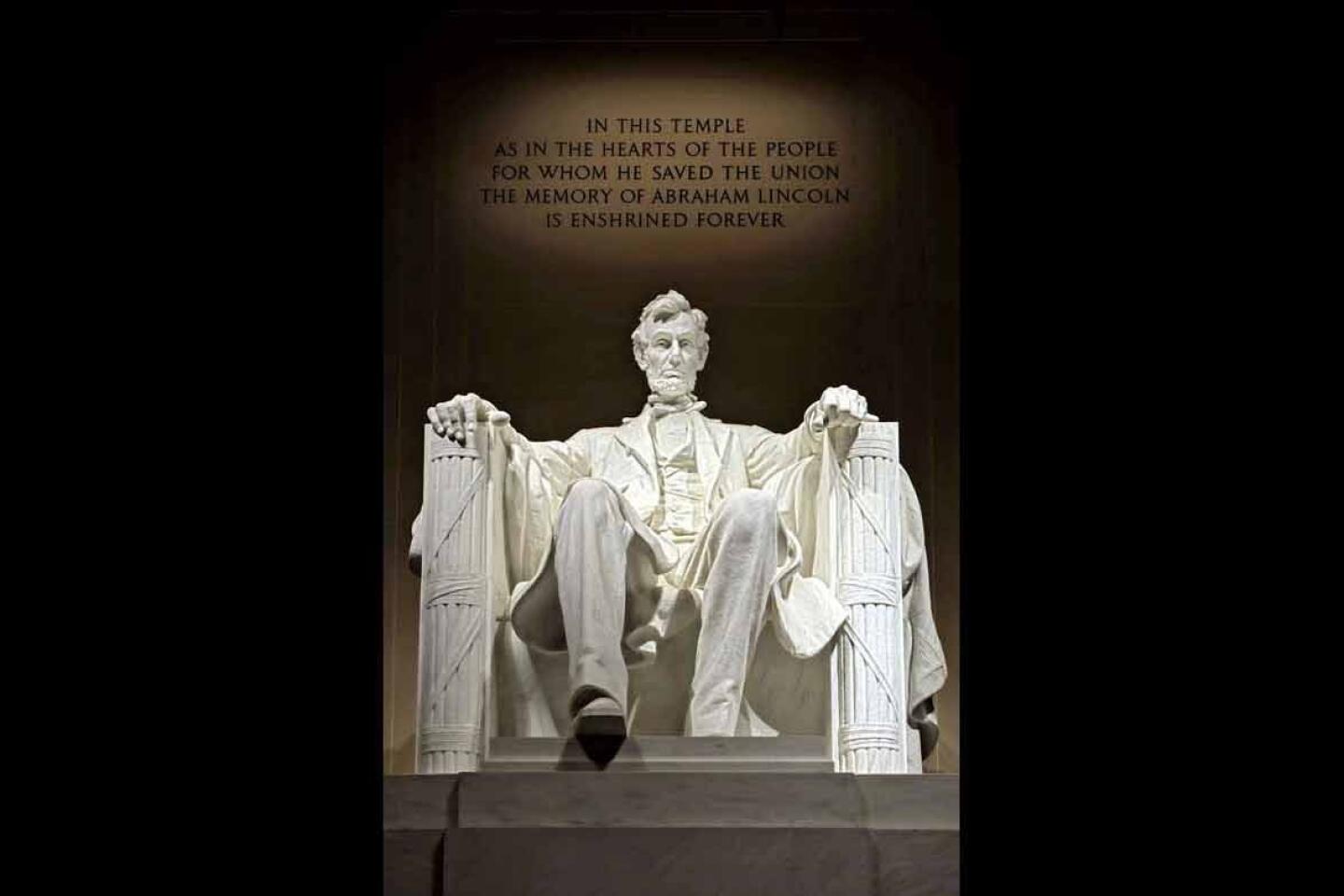

But the best-known marker anchors one end of the National Mall — the Lincoln Memorial. If visiting Ford’s Theatre puts the assassination on a human scale, then the memorial, with its giant white marble statue of Lincoln in an armchair, does the opposite, reflecting the outsized role Lincoln plays in U.S. history.

And its permanence reinforces something Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton said shortly after Lincoln breathed his last: “Now he belongs to the ages.”

Scott Martelle, a Times editorial writer, is the author of “The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man Who Killed John Wilkes Booth.”

MORE FOR LINCOLN HISTORY BUFFS:

Lincoln’s slaying recalled at Ford’s Theatre

Visiting Gettysburg, Ford’s Theatre and other sites

Illinois will relive Lincoln’s assassination and funeral

Re-creation of Lincoln rail trip to Springfield, Ill., is scrapped

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.