Book excerpt: The day Jackie Robinson came home to Dodger Stadium

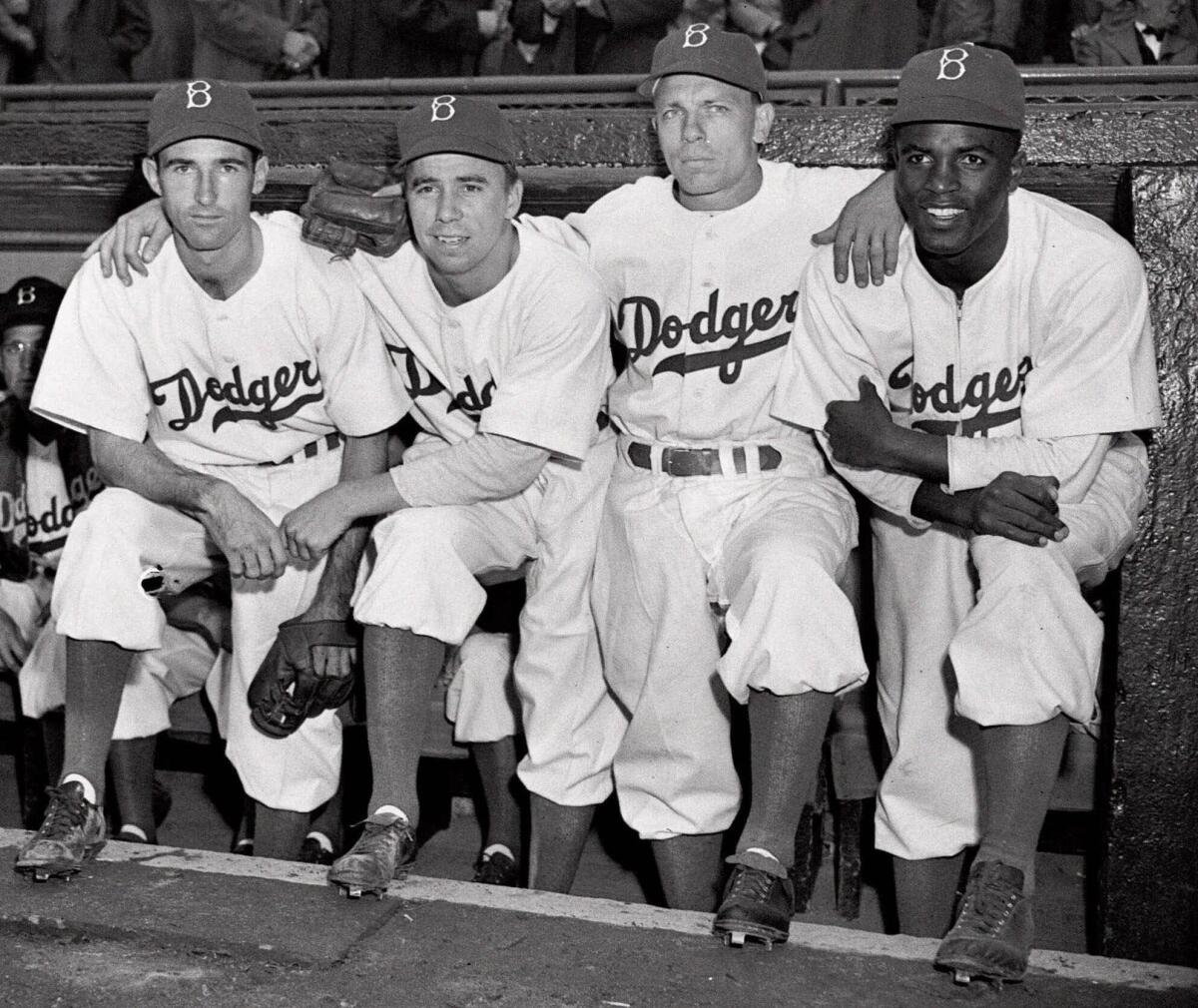

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first Black player in MLB history, beginning a decadelong Hall of Fame career with the Brooklyn Dodgers. A trade to the New York Giants after the ’56 season began a lengthy estrangement from the Dodgers and baseball.

In this excerpt from “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” author Kostya Kennedy traces the path that brought Robinson to Dodger Stadium on June 4, 1972, for the 25th anniversary of his breaking baseball’s color barrier, less than five months before he would unexpectedly die at age 53.

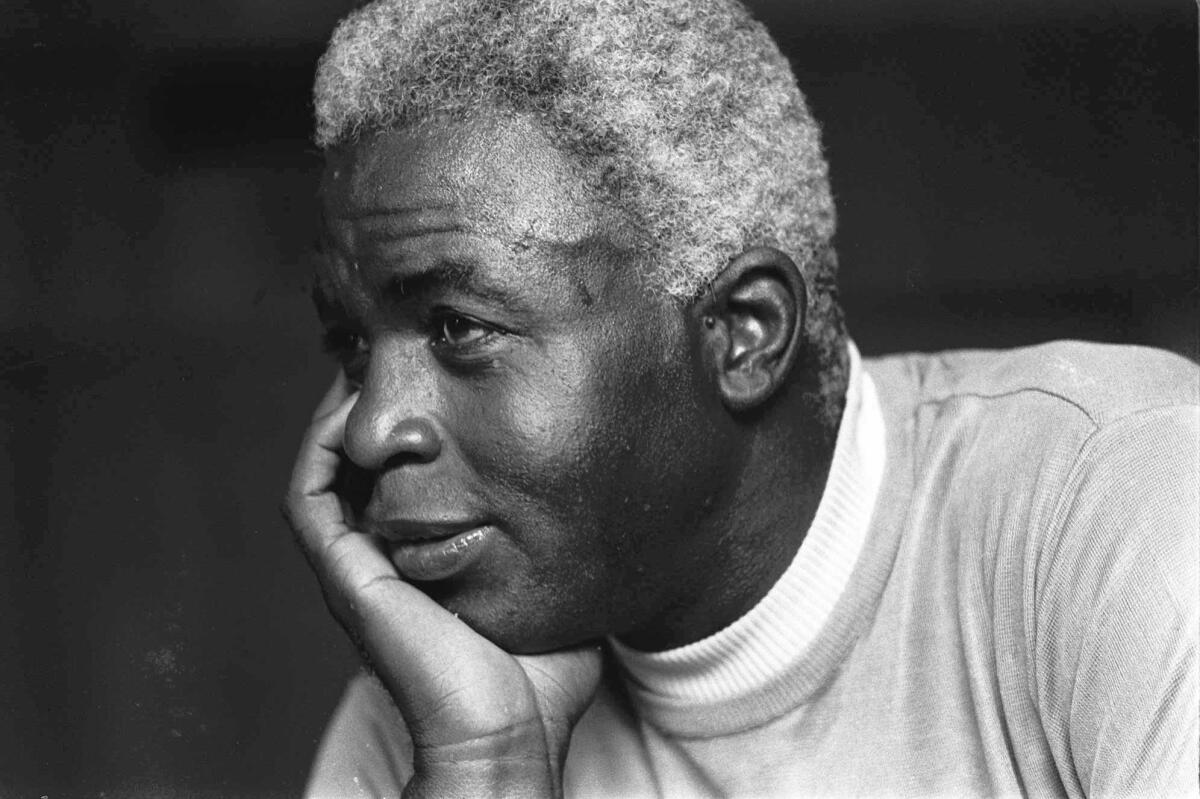

Jackie Robinson had not been inside a baseball stadium for years. Since his retirement in 1956, he’d had no official or professional connection at all to Major League Baseball — which he openly criticized as negligent in its treatment and integration of Black players in their post-playing careers. How could he not? Twenty-five years after Robinson broke in, more than fifteen years after his final game, no team had hired a Black manager or general manager, and very few Black players held jobs of significance in the game. It was a conspicuous element of Robinson’s protest that he did not attend Old-Timers’ Games or other stadium celebrations. He’d stopped being invited, because his answer was always the same.

Former Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Carl Erskine was teammates with Jackie Robinson from 1948 to 1956. He recalls his relationship with the man who broke baseball’s color barrier.

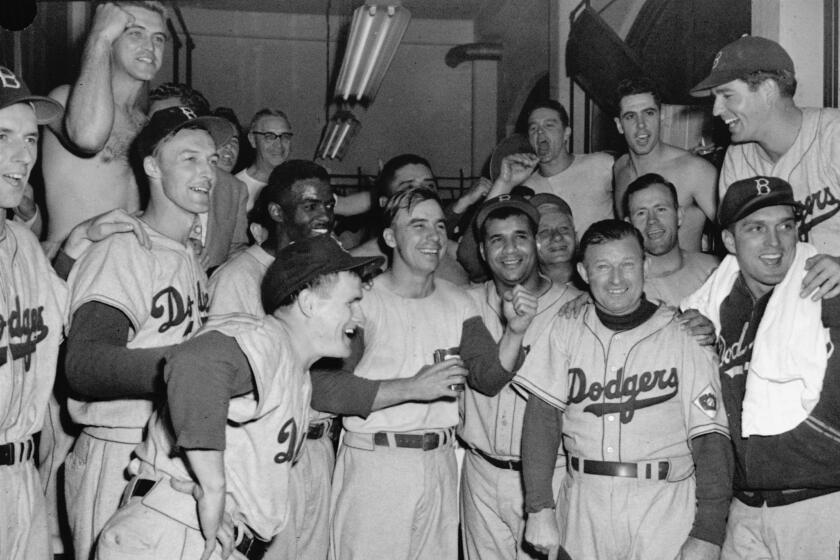

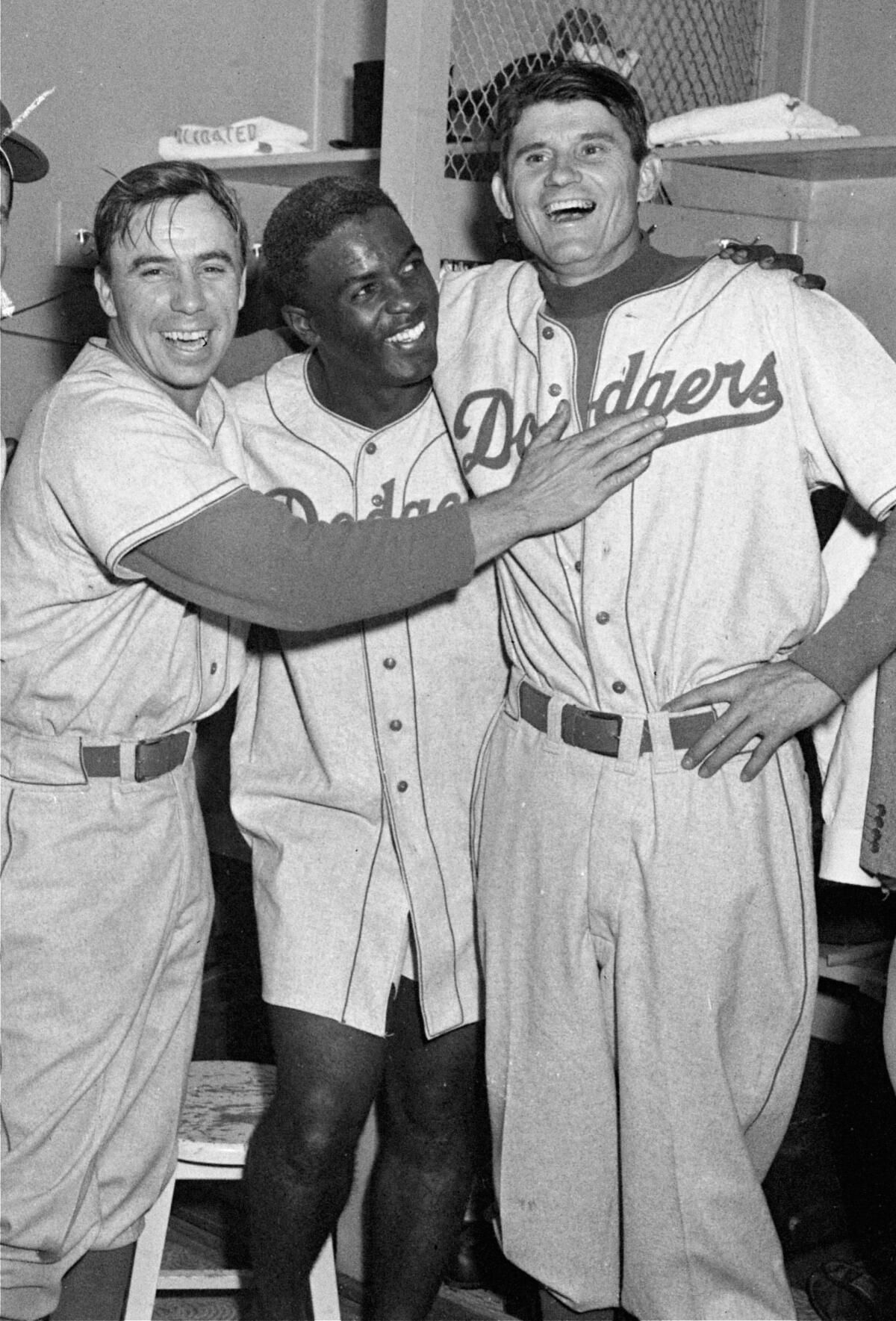

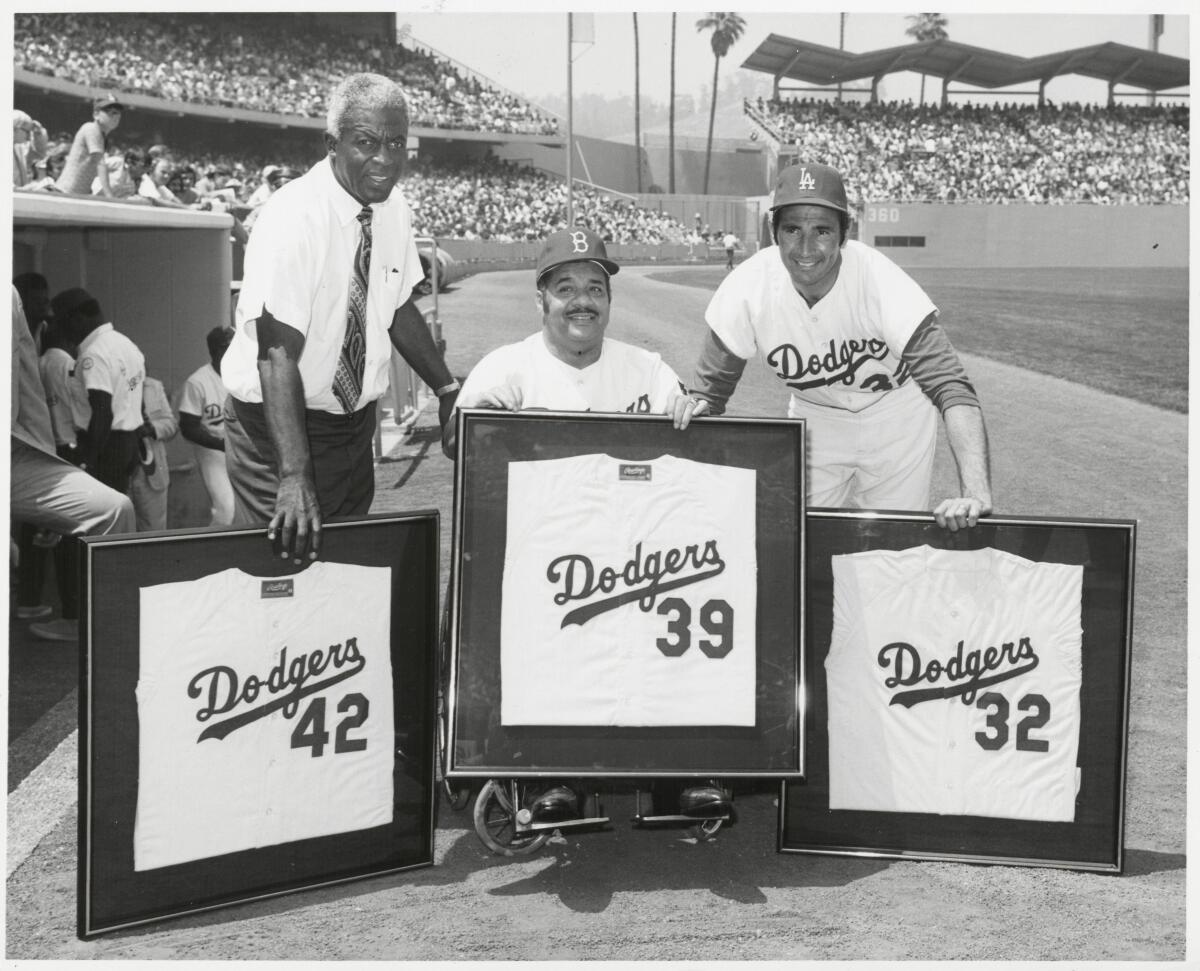

But then, at the funeral of Gil Hodges earlier that spring, Robinson had seen so many of the old guys together, and he had spoken with Don Newcombe, for whom he retained a warm affection. Newcombe did have a connection to baseball, as a community relations liaison for the Dodgers and team president Peter O’Malley. Sensing in their conversations and reminiscences the earliest edges of a thaw, Newcombe invited Robinson to come to Dodger Stadium later in the spring, on the first Sunday in June. In an on-field ceremony before that season’s Old-Timers’ Game, the Dodgers planned to retire the uniform numbers of three former players who’d reached the Hall of Fame: Roy Campanella’s 39, Sandy Koufax’s 32, and Jackie Robinson’s 42. Newcombe, Pee Wee Reese, and Jim Gilliam would be there and others as well. A bunch of the old Yankees. Stan Musial. Newcombe worked on Robinson a bit, and so did Tommy Villante, who recalls, “We had to kind of convince Jackie that Peter O’Malley wasn’t just the same guy as Walter, who Jackie still felt wary about.” Robinson said yes.

“jackie robinson-dodger feud ends” read a headline in the Long Beach Press-Telegram on the day of the event in Los Angeles. Separate and apart from his dissatisfaction with baseball as a whole, Robinson had a more particular friction with the Dodgers themselves, stemming not from issues around race but from his divide with Walter O’Malley and the galling trade of 1956. Trade discussions had circulated around Robinson for some time, and to many, a trade made sense: Robinson was an older, expensive player with his best years behind him but still capable on the field and, as ever, a draw at the gate. And yet it seemed that Robinson, with his long and numinous reach, should have been beyond such mundane calculus. Trading him was akin to excising the lion’s heart. O’Malley, then, exhibited a particularly pointed flex of might when on December 13, 1956 — a little more than two months after the final out of the World Series, and 299 days before O’Malley officially pulled the Dodgers out of Brooklyn, bound for Los Angeles — he traded Robinson to the rival Giants.

General manager Buzzie Bavasi delivered the news by telephone to Robinson, who smiled (or did he grimace?) on his end of the line. Privately, Robinson had already moved on. Shortly before learning of the trade, but already with an inkling of it, he had decided to retire from baseball, accepting a position as a vice president overseeing personnel at the Chock Full o’ Nuts restaurant chain in New York. Robinson, keeping those plans private (to be revealed weeks later in a paid-for Look magazine story), made no mention of the Chock Full job to Bavasi. So the trade to the Giants was announced, and it rent a gash through the Dodger zeitgeist. Robinson publicly thanked the Giants owner Horace Stoneham for wanting him, and in the following days, he and Jackie Jr. held up Giants’ pennants and posed for the photographers who came to visit the home in Stamford, Connecticut. During the time between the trade and Robinson’s writing to Stoneham, in early 1957, on Chock Full o’ Nuts letterhead, to say that he would not in fact report to spring training, that he was leaving baseball for “business opportunities,” Robinson received a welcome-to-the-team telegram from the Giants’ twenty-five-year-old center fielder, Willie Mays.

Robinson knew that Walter O’Malley remained an ally in baseball’s path to progress, and he knew that his wife, Rachel, had a fine and gentle relationship with Kay O’Malley, Walter’s wife, and yet in the aftermath of the trade and in the decade and a half since, Robinson and the Dodgers had not gone anywhere or done anything hand in hand. In 1972, the conflicting emotions of a breakup — I don’t need you. I love you — still weighed on Robinson. “I couldn’t have cared less about the trade, because I had already made my decision to retire,” he said as the Old-Timers’ Day in Los Angeles approached. “But I was hurt by it, yes. After you give everything you have to one team, it’s hard to be traded.”

In 1970, Walter O’Malley had moved himself into the Dodgers’ chairmanship and given daily control of the team to his son, Peter. During the repatriation of Robinson in ’72, Peter O’Malley said he could not imagine allowing a trade such as the one of Robinson. The franchise’s greatest player? The critical baseball figure of his time? That would never have happened on his watch, Peter O’Malley said. He framed the trade of Robinson as an organizational regret.

::

Sometimes during his later life journey, Jackie would remark that baseball seemed far away from him and somehow part of a different, other life. He observed that if he had remained in the game, as he had once wanted to do as a manager or front-office sharp, he would have been confined to “a narrow strata” that he was now pleased to have outgrown. The environment and details of baseball — being embedded with his teammates, sharing the priorities and urgency of the effort, having the competitor’s inevitable in-game notion that the outcome of an at bat or an umpire’s call bore some existential truth — all of that had changed. He didn’t go to the ballpark or watch games much on TV. He didn’t parse the standings. His closest friends had no connection to the sport.

Upon his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1962, Robinson asked that his plaque make no mention of his role in integrating baseball. The plaque cited his career batting average and his MVP award, his stolen bases and his defensive excellence at second base. Nothing else. Nothing about being the first Black ballplayer of the twentieth century. No discussion of his brilliant, attacking approach on the field. No nod to the circumstances under which he played. The plaque read as Robinson wanted it to. His aspiration hadn’t changed: Hell of a ballplayer, Robinson, and just one of the guys.

Aeschylus in framing his legacy decreed that the inscription on his gravestone bear no allusion to the plays that had made him famous, but only to his service as a solider in the defense of Athens and Greece — even though his written words, the tragedies, were what publicly distinguished his irreplicable life and would make him immortal. All of it, of course, intertwined. No “Agamemnon” or “The Persians” had Aeschylus not gone to war. Nor, in the case of Robinson, could there ever be any extrication of baseball from his message, or his message from the arena of baseball — no matter what the plaque in Cooperstown read. For all the years that he and the sport kept each other at arm’s length, and for all the emphasis Robinson placed on a life outside the game, there was something more than simply fitting, but rather inevitable, that in the final year of his life, 1972, Robinson came back to baseball, and baseball came back to him.

::

Robinson stood talking with a couple of the Dodgers executives — team president Peter O’Malley, the PR director Fred Claire — and some former players on the field at Dodger Stadium, just in front of the dugout on the third base side. Newcombe and Koufax and Gilliam were gathered with them, and it was about an hour before pre-game ceremonies. The low clouds of morning had moved away, and the late spring air and warming sunshine, Robinson said, reminded him of his youth. Robinson always liked going home to California. Sometimes he saw his brother Mack. Recently, at a studio on Sunset Boulevard, Robinson had filmed an episode of the “Sports Challenge” quiz show, competing on a team with Duke Snider and Carl Erskine against three members of the 1972 Dodgers: Wes Parker, Frank Robinson, Maury Wills.

Batting practice was under way, and from the stands fans shouted players’ names, as they always did before ball games, as they had on all those days and evenings back in Brooklyn. From just behind the Dodger dugout, a man leaned forward, holding a baseball. “Hey, Jackie, Jackie! Would you sign this?” he called out, and then he tossed the ball in a gentle arc toward Robinson. “It hit him in the shoulder right up near his cheek,” Claire recalls. “He couldn’t see it, let alone catch it.”

Immediately the group circled around to make sure Robinson was all right and then started pointing toward the stands. “Everyone was saying, ‘Get that guy out of here! Get rid of him,’” Claire says. “But Jackie raised his hand and said, ‘Calm down, calm down. Can someone hand me the baseball?’ He signed the ball and said, ‘Please give this back to the gentleman.’ And that was it. I was so impressed by how poised he was. His humility and his presence took over. But it was sad how he couldn’t catch the ball.”

Robinson’s vulnerability that day was new to the many who had not seen him in some time, and it delivered a particular, sobering force given its contrast to the physical impression he had once made — the imprints that would always remain. “The greatest athlete I ever saw,” Newcombe declared during the Old-Timers’ Game weekend. (Robinson, it’s worth remembering, was a man who had in his trophy room both a silver bat from Major League Baseball and a bronzed football cleat from UCLA.) In recent months, his physical decline had accelerated. Driving, as he had driven himself to Gil Hodges’ funeral, was out of the question. He stepped uncertainly when not being guided. He moved stiffly through his arms and shoulders. At times, he drew short of breath. Recalling Robinson’s condition about a week after the event in Los Angeles, Campanella wept. “Just goes to show, I guess, how the years can make a difference,” said Campy, wiping his cheek.

::

The Dodgers drew 43,818 fans on that Sunday, June 4 — the largest day-game crowd the team would attract all season. It was a bright, beautiful afternoon, and the great Bob Gibson was fixing to pitch for the visiting Cardinals. Along with Campanella, Koufax, and Robinson having their numbers retired, a host of stars had come for the game. DiMaggio, Mantle, manager Casey Stengel, who was being feted. Yet no one received greater applause or generated more discussion or warmth than Jackie Robinson, a repatriated son, as it were. In the lead-up to the number ceremony, he sat in the Dodger dugout, at the end of the bench near the bat rack, and players and staff approached him with greetings and thanks. “His signature was still fine, the lettering was strong,” says Mike McDermott, the Dodgers batting practice pitcher who asked Robinson to sign a baseball for him that day.

For the ceremony itself, the three former Dodgers came out onto the infield, along with Peter O’Malley and commissioner Bowie Kuhn, and received framed replicas of their respective uniforms. An aide pushed Campanella in his wheelchair. Koufax, who had been named to the Hall of Fame just a few months before, told the crowd that the two players beside him had been heroes of his growing up in Brooklyn. He would never have imagined, Koufax said, that he would one day be standing on the field beside them on a day as remarkable as this. When Robinson stepped to the microphone, he said: “This is one of the truly great moments of my life. I’m grateful for everything that has happened.” Campanella and Koufax wore their Dodger jerseys — Koufax in full uniform — but Robinson wore shirt-sleeves and tie, and on his left wrist a watch he’d received from Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in 1947, twenty-five years before, the year he had broken into the major leagues.

Kostya Kennedy discusses “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” which takes on pivotal years in the life of baseball’s first Black player.

Earlier during the Old-Timers’ Game weekend, Robinson had met with Peter O’Malley at O’Malley’s office at Dodger Stadium, to mend bridges and to talk about some issues that Robinson felt needed talking about: specifically the advancement of Black former players into baseball management. “I was very much impressed with Peter’s attitude,” Robinson said afterward. “I don’t know what he can do about it, but first of all there has to be sensitivity to it.” All that weekend — around the field, at a luncheon for the honored guests — Robinson spoke so well of Peter O’Malley that a rumor, half baked and only half in jest, sprang up that he might take a job in the front office of the team. “Dear Pete,” Jackie wrote shortly afterward from home in Stamford, “I also want you to know how pleased I was with our meeting at which was sensed a truer understanding of the nature of the things that evoked problems between baseball and me.”

This article has been adapted from “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson,” by Kostya Kennedy. Copyright © 2022. Reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press. You can purchase the book here.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.