Column: Don Newcombe’s toughness helped him overcome hate and become a legend

Los Angeles Dodgers manager Dave Roberts comments on the passing of Don Newcombe.

He could have been the angriest man at Dodger Stadium.

Instead, he was the most elegant.

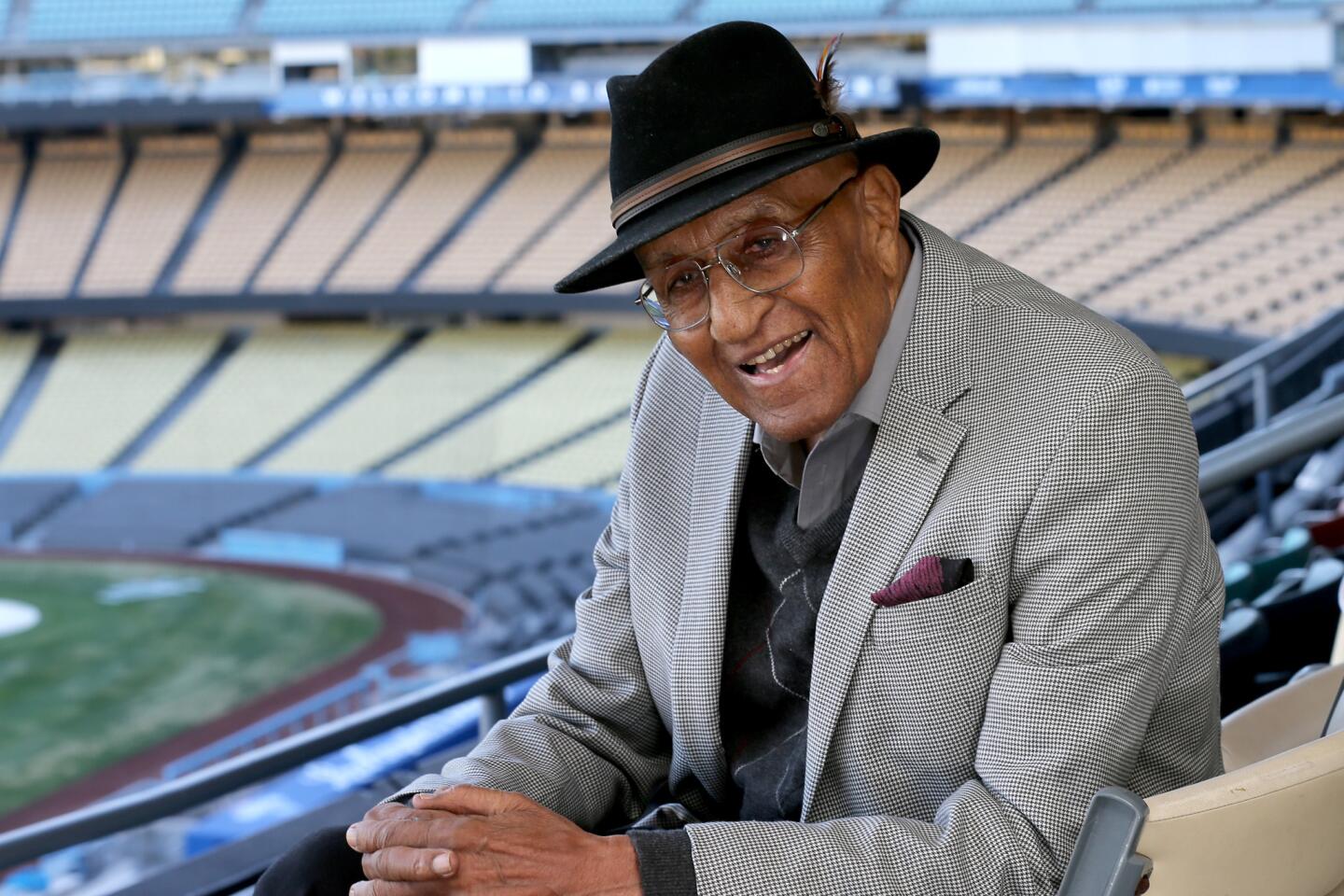

Don Newcombe, who died Tuesday, was a monument in a fedora, history with a sport coat, a legend bearing a pocket square.

Even when his memory was fading and his steps were slow, he would show up three hours before every Dodgers home game as if dressing for church. His pew was a seat behind home plate. His congregation was countless players, media and officials who would stop, sit and listen. His message was love.

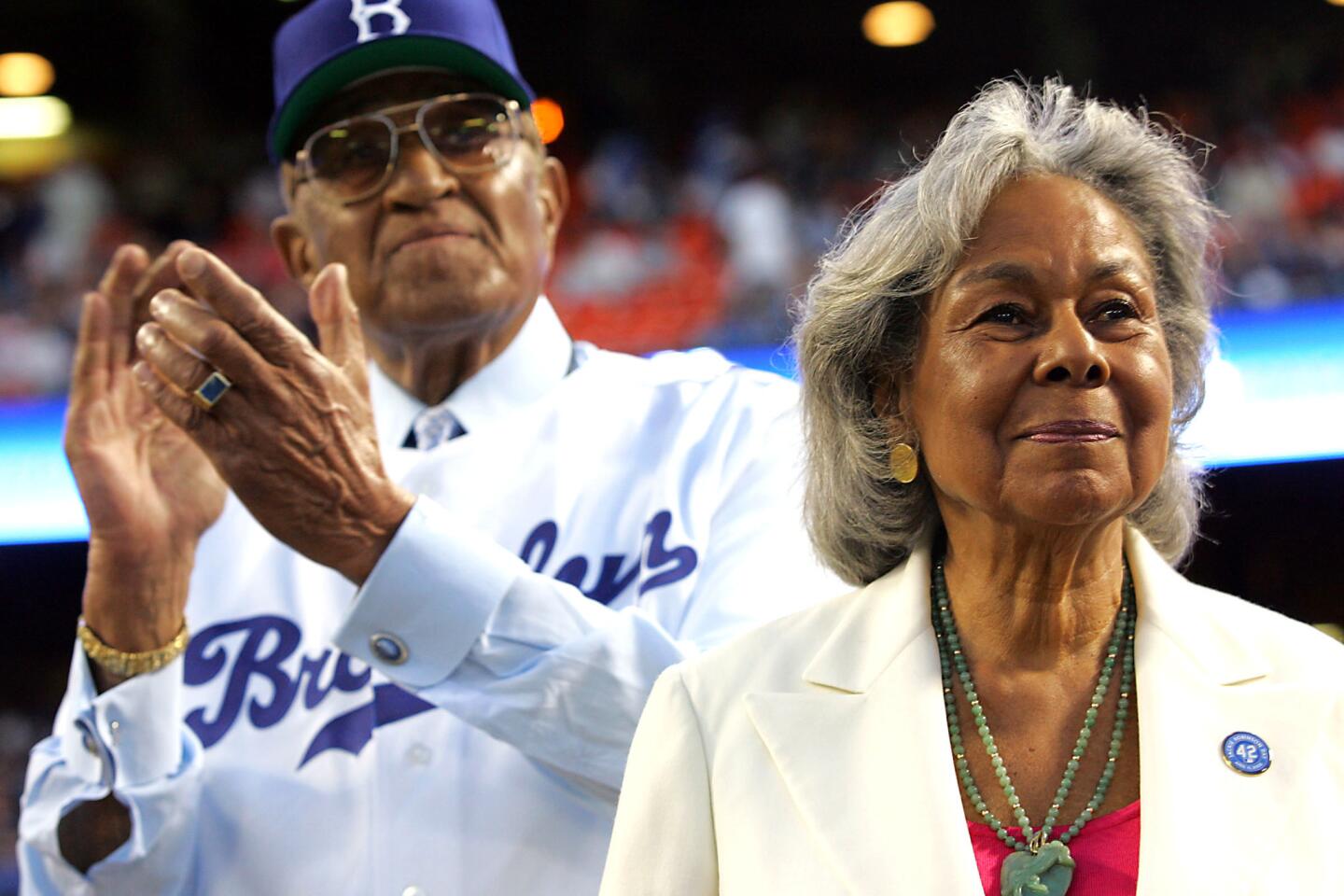

“I remember Jackie calling me and Roy together at Roy’s apartment after we first signed,’’ he told me, referring to Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella. “Jackie said that people were going to hate us and abuse us, but by changing one letter in one word we can make a difference.’’

He paused, waited for me to ask him for the word and letter, then smiled.

“Bitter,’’ he said. “I to E.’’

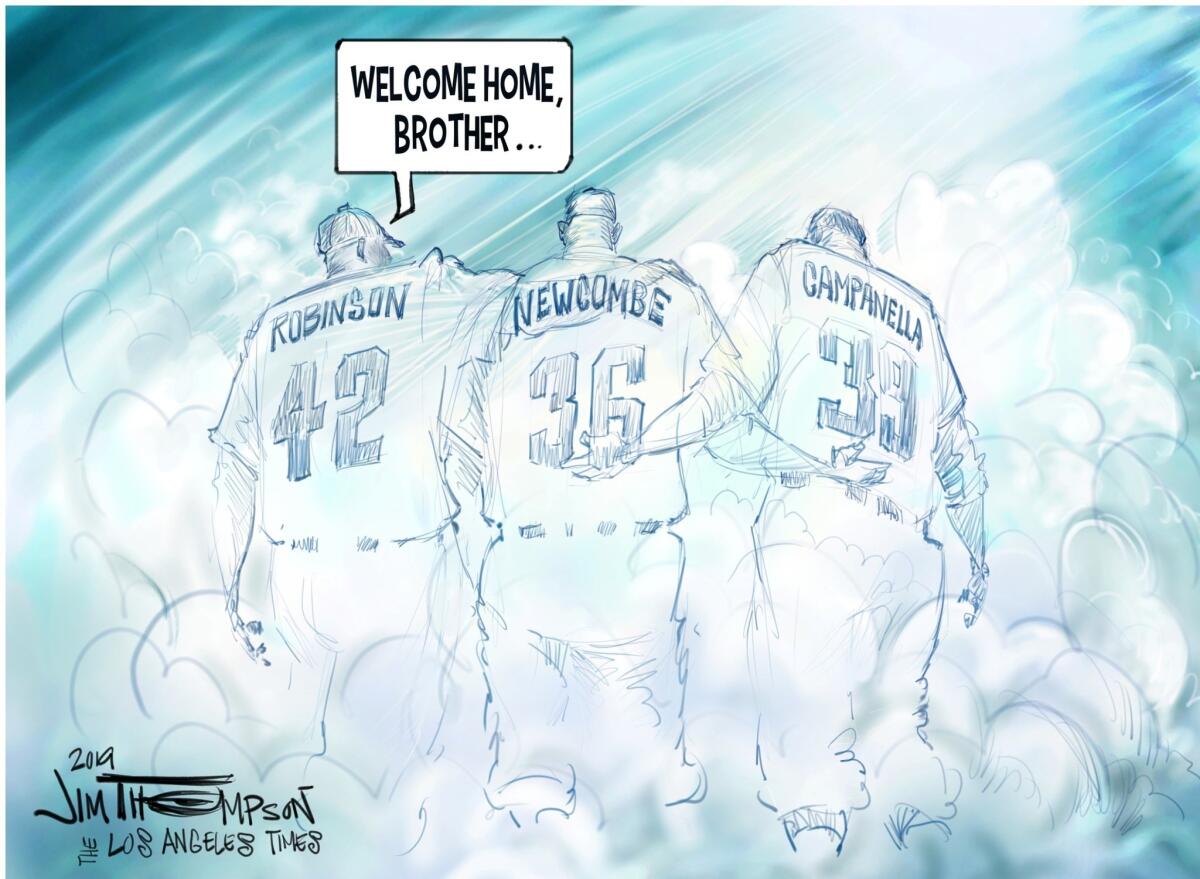

Better. That was Don Newcombe, better than the hate he endured as one of baseball’s first African American players, better than his personal demons of alcoholism and cancer, better beyond belief in 92 years of a life lived with an unrelenting toughness coated in an uncommon dignity.

“[Robinson] said we should fight to be better, not bitter, and sure enough, that’s what happened,’’ Newcombe said.

That fight ended Tuesday morning with his death from prolonged illnesses. He died peacefully in his Los Angeles home with his wife, Karen, at his side. In his last words, he told her he loved her, which is just like Newk, speaking one last time from the heart.

I saw this during our many visits over many years at that seat behind home plate. After conducting my pregame interviews in the dugout, I would stop by and say hello to him on my way back to the press box.

He would point to an adjacent chair and invite me to sit down next to him. He would then put his giant hand on my shoulder and begin to talk.

First, he would ask about me. He always asked about me, my upcoming stories, my personal life, and I always had the same thought: This is baseball’s last living bridge to Jackie Robinson and he cares about my challenges?

Then he would give advice. He loved to give advice, especially dating advice, often looking over at wife Karen.

“The right person can save your life,’’ he said. “She saved my life.’’

My visits with him, which ultimately ended when he would head upstairs to watch the game from a suite, were the best part of my day. He was more than a legend, he was a friend, an uncle, a wise and generous man who unconditionally shared both his joy and pain. Sometimes he said nothing, we just stared together at the field in silence, watching the Dodgers taking batting practice. I often wondered what he was thinking.

Once, he told me, and it was horrifying.

“I still remember them pulling up to the hotel for blacks in St. Louis, and Jackie and Roy and I had to get off the bus,’’ he said. “And none of the Dodgers got off the bus with us. None of them. They were all going to the whites’ hotel, and they just watched us walk away. I love the Dodgers, but I’ll never forget how they stayed on that bus.’’

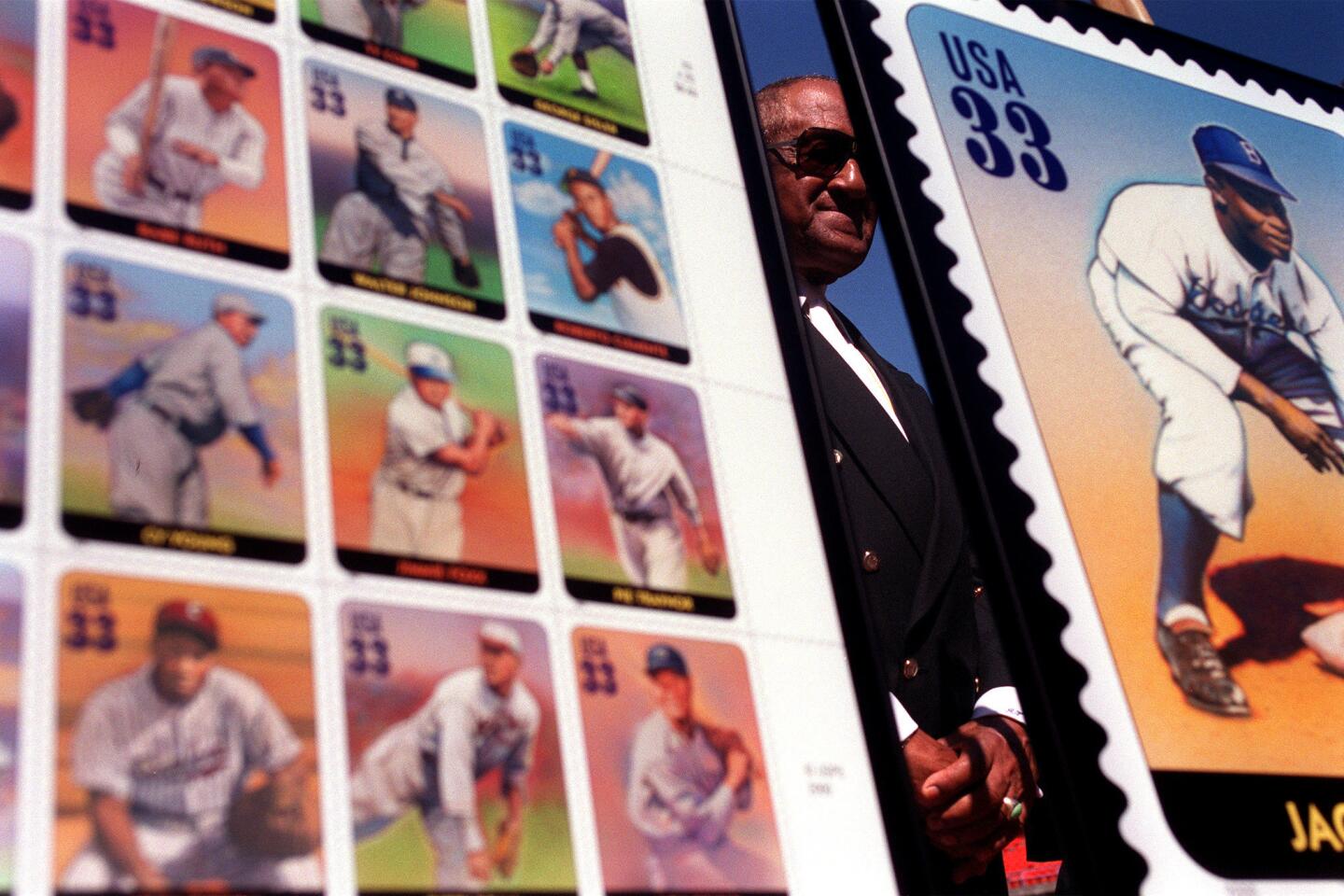

Somehow, Newcombe quietly endured, forcing baseball to integrate against its will, changing the game forever with his powerful presence. The tall right-handed pitcher wasn’t the lone pioneer that was Robinson, but he was right behind him.

Just like Robinson, Newcombe and Campanella signed with the Dodgers out of the Negro Leagues in 1946. Newcombe made his Dodger debut two years after Robinson in 1949, and was Robinson’s roommate on the road for his first two seasons.

Newcombe became the first African American pitcher to start a World Series game, the first African American pitcher to win 20 games, and one of the first four African Americans to integrate the All-Star game in 1949.

He was also the first player of any ethnicity to win rookie of the year, Cy Young and MVP awards, an accomplishment matched only by Justin Verlander.

He had a record of 27-7 with a 3.06 earned-run average during his career year, 1956. He is not in baseball’s Hall of Fame, but he deserves to be reunited with Robinson and Campanella in the Dodgers’ Ring of Honor, and here’s hoping the organization finally does the right thing and puts him there.

More than anything, he was strong. Witness his performance in Chicago one day when the catcalls were particularly loud.

Robinson visited the mound and told him, “Hey, sometimes if the ball slips out of your hands, and goes up under a batter’s chin, don’t feel bad, because they don’t feel bad when they throw at me and Roy.’’

Newcombe knocked down the next seven batters, leading to his ejection from the game despite his unique protests.

“I said, ‘You can’t throw me out until I get the other two,’ ’’ he recalled.

Newcombe would tell stories like this as we sat behind home plate, watching the diverse creation of his efforts playing out on the field before us. Every bit of humor was tinged in a certain sadness.

There was the time he faced Joe DiMaggio in the All-Star Game and had never before seen him play because they had been previously segregated.

“Back then, what would a black player know about Joe DiMaggio,’’ he said with a laugh.

When talking about the struggles of the Dodger bullpen, he would counter with stories about pitching in the bullpen surrounded by security because of death threats.

“We started the civil rights movement, but Branch Rickey told us to make it only about baseball,’’ he told me. “We had to tear this terrible barrier down with only a baseball.’’

Yet, when reminded how much the game seemed to owe him, he would always turn it around.

Kenley Jansen discusses the impact Don Newcombe had on him. (Jorge Castillo / Los Angeles Times)

“Looking out at this stadium today, it’s like a wonderful, wonderful dream being answered, just to be here,’’ he told me when we met during a winter day at Chavez Ravine. “I’ve loved the Dodgers from the day they signed me and Campy and Jackie, and I will love the Dodgers as long as I live.’’

He shared that love with current players who would visit with him before games, most notably Kenley Jansen, who would sit down in the stands in full uniform and, like all of us, talk with Newk about life.

“From now on, I call you Dad and you call me son,’’ Jansen once told him.

My last visit with Newk was in October, before a Dodgers World Series game against the Boston Red Sox. Because there were so many people around the batting cage, he couldn’t watch batting practice from his usual pregame seat. So he regally headed for the Dodger dugout, his usual sport coat and fedora clashing brilliantly with the pine tar and bubble gum.

Karen and I helped him down the steps. He looked pained and tired until he was seated on the dugout bench. Then, he sighed and smiled. Nobody noticed him. He and I sat alone for the longest time, but he was happy, because for one of the last times, the best-dressed Dodger was home.

“When I was young, I had nothing,’’ he told me once. “I borrowed my brother’s suits, I wore my teammates’ suits. I always told myself, if I ever made it …’’

Don Newcombe not only made it, he made it better, for baseball, for society, for a world that never saw the bitter, for that seat behind home plate that will never again be so gloriously filled.

Sign up for our Dodgers newsletter »

Get more of Bill Plaschke’s work and follow him on Twitter @BillPlaschke

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.