Virus outbreak creates new challenges for addiction recovery

SEATTLE — Charlie Campbell has been sober nearly 13 years. These days, it’s harder than ever for him to stay that way.

His dad is recovering from COVID-19 in a suburban Seattle hospital. His mom, who has dementia, lives in a facility that now bars visitors because of the coronavirus. A good friend recently killed himself.

Last week, Campbell, 61, tried his first online Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. His internet connection was shaky, and he didn’t get to speak. The meeting did not give him the peace and serenity he craved.

“I’m a face-to-face kind of person,” Campbell said. Still, he hasn’t relapsed.

The coronavirus pandemic is challenging the millions who struggle with drug and alcohol addiction and threatening America’s progress against the opioid crisis, said Dr. Caleb Alexander of Johns Hopkins’ school of public health.

People in recovery rely on human contact, Alexander said, so the longer social distancing is needed, “the more strained people may feel.”

Therapists and doctors are finding ways to work with patients in person or by phone and trying to keep them in treatment. And many are finding new reservoirs of strength to stay in recovery.

In Olympia, Wash., a clinic for opioid addiction now meets patients outdoors and offers longer prescriptions of the treatment drug buprenorphine — four weeks, up from two — to reduce visits and the risk of infection, said medical director Dr. Lucinda Grande.

Elsewhere, federal health officials are allowing patients to take home methadone, another treatment drug. And they issued emergency guidance to make it easier for addiction professionals to offer help by phone without first obtaining the written consent required to share patient records.

Forecasts for economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic have quickly turned much darker – both for the depth and duration of the damage.

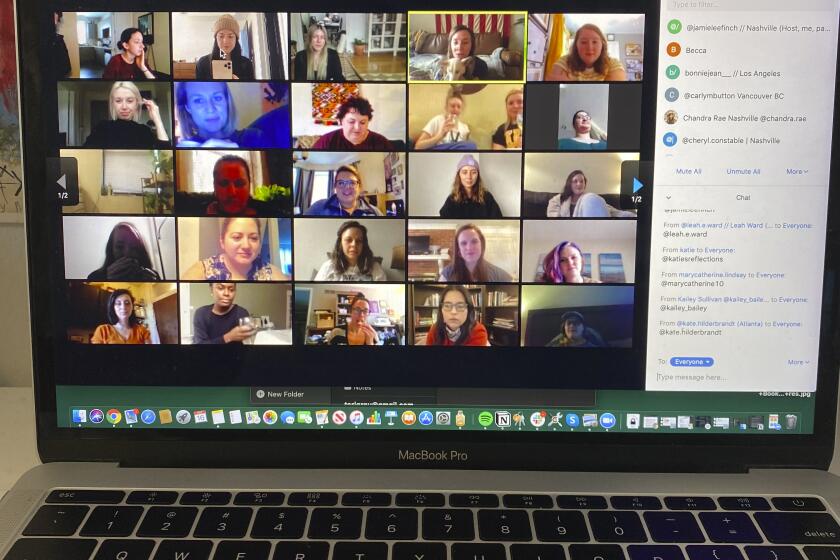

With cities and states locked down, online support groups are forming, among them a global group started by a San Francisco-area tech worker that’s called One Corona Too Many. In the New York City metro area, with more than 6,000 meetings weekly, organizers offer guidelines on best practices and tutorials on how to set up video conference calls.

Reagan Reed, who leads the Inter-Group Association of AA of New York, said there had been snags. Some groups did not know how to change settings to private; others have gone over capacity, revealing phone numbers.

In suburban Boston, Catherine Collins, a 56-year-old recovering alcoholic, said it had been an adjustment to attend AA meetings via the online platform Zoom.

Collins, who has been sober since 1998 and works for Spectrum Health Systems, the state’s largest addiction treatment provider, says preserving some social interaction is critical for those in recovery.

“People need to be talking about what’s happening in the world, because if they’re not, they’re at risk of picking up a drink,” she said. “It’s more important than ever now to have hope, and that’s what these meetings give.”

Is the phrase “social distancing” sending the wrong message to millions of Americans struggling to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic? Some experts think so.

Job loss is a gut punch to some, just as they begin to rebuild their lives.

Courtney Keith, a waitress and the mother of a 13-year-old girl in Toledo, Ohio, said she spent the last four years paying off fines because of her past trouble when she was addicted to drugs and alcohol. She lost her job when the state banned sit-down dining.

“I was living paycheck to paycheck. I have no savings,” the 33-year-old said. She’s applied for a job at a grocery store and dug through her loose-change stashes, scraping together a few hundred dollars.

She keeps in close touch with her recovery sponsor.

“I haven’t had any thoughts about using, but everybody is different. What if this does lead to a mass relapse?” she said.

Richie Webber, 28, who survived a 2014 fentanyl overdose and now works as an addiction counselor in Clyde, Ohio, said he’d heard people during online meetings say they’d already slipped.

“They’re really trying to keep it from falling back into full-blown addiction,” Webber said.

“Isolation is really worrying for me,” he said. “If you’re shut up in your house, your windows are closed, you’re going to get depressed.”

Campbell, a retired nurse, is driving from his home in New Mexico to Washington state to check in on his parents again. He got some good news last week: His dad’s latest COVID-19 test was negative.

He says he’ll try online meetings again but plans, mostly, to lean on phone calls with a longtime buddy and the emotional support of his wife.

“In the short term, you’ve just got to walk the middle line and try to find the good in all this,” Campbell said, “and know it’s not going to last forever.”