Isolation is hazardous to your health. The term ‘social distancing’ doesn’t help

Is the phrase “social distancing” sending the wrong message to millions of Americans who are struggling to get by during the COVID-19 pandemic?

That’s the case being made by Daniel Aldrich, director of the security and resilience program at Northeastern University in Boston.

“The moment I heard public health authorities use the term, I thought they were making a mistake,” he said.

Aldrich, along with the World Health Organization and a growing number of governments, prefers the phrase “physical distancing” to describe interventions such as working from home, closing schools and maintaining at least 6 feet of space between people to reduce the spread of the new coronavirus.

Referring to those measures as “physical distancing” is more specific, more accurate and could ultimately save more lives, he said.

Aldrich fears the phrase “social distancing” suggests we should be turning inward and closing ourselves off from friends and neighbors in the outside world.

“That’s the exact opposite of what we want people to do,” he said. “You need to have as close social ties as possible when physical distancing is in effect.”

Aldrich studies how social connections affect death rates after disasters like hurricanes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis. Time and again, his research — as well as the work of other social scientists — has shown that when vulnerable people are part of a social network, their chances of survival are better.

“We have a lot of people in our society who are vulnerable — young people, the elderly, people who are sick, or who aren’t fed well” he said. “But it’s when vulnerability interacts with isolation that morbidity goes up.”

Daily life feels very different now that we are living with the coronavirus. Psychologists offer their advice for learning how to get used to it.

For example, in a 2015 paper that looks at survival rates in different communities after Japan’s devastating Tohoku earthquake in March of 2011, Aldrich and his colleague found significantly fewer deaths from the resulting tsunami in communities that had more social cohesion.

“We have all these tales of people who only survived because somebody came to their house, knocked on the door and said, ‘You are coming with me,’” Aldrich said.

This relationship between vulnerability and isolation was also highlighted in Eric Klinenberg’s book “Heat Wave,” which examined a 1995 heat wave in Chicago that left more than 700 people dead.

It wasn’t just elderly people who died, Klinenberg found — it was elderly people who had nobody to take them to a cooling center, or even help them open a window in their apartment.

Aldrich also cites his own experience living in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005.

“The reason we survived is not because we listened to the evacuation order — we didn’t,” he said. “We survived because a person we had just met knocked on our door and said, ‘You need to go.’”

Social support is also essential in the days, weeks and months after a disaster has occurred, said Alison Holman, a health psychologist at UC Irvine.

Her research has found that people who received social support in the two months after the Sept. 11 attacks were able to focus on the future and exhibited less stressed on the one-year anniversary of the event than those who did not.

“Staying connected is a way to stay grounded,” she said. “It keeps you from being pulled into a state of sheer anxiety.”

It’s only natural that you’re obsessing about the coronavirus, but that anxiety is neither healthy nor necessary. Here’s why you should stop, and how to do it.

Cultivating social connections while practicing physical distancing can also keep people from sinking into despair during a time of uncertainty and disruption, said Andrea Graham, a professor of medical social science at Northwestern University.

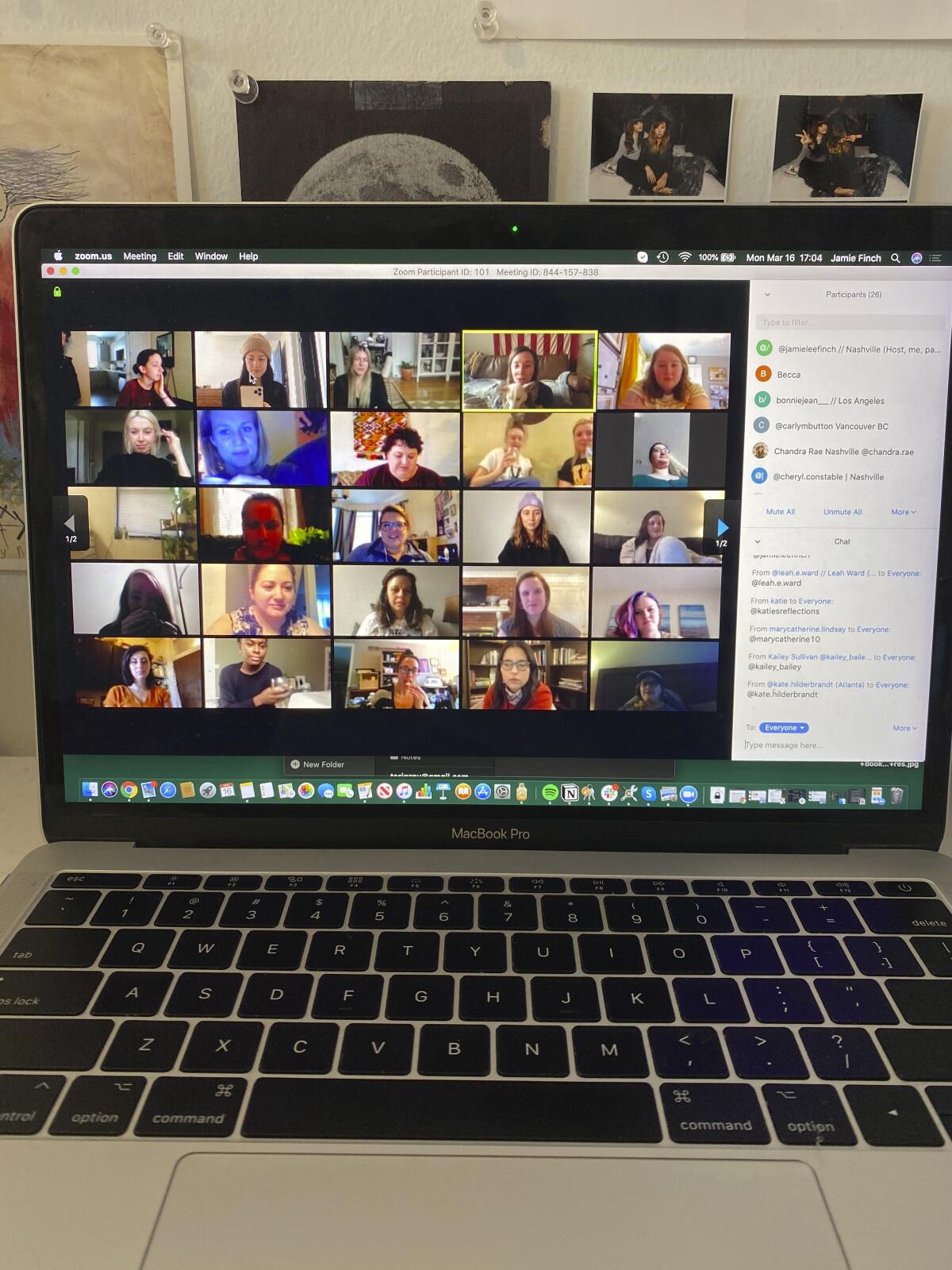

“It’s important for us to maintain a positive outlook,” Graham said. “Getting together with co-workers and friends via digital platforms has allowed people to keep some degree of connection and routine in what has otherwise been a very difficult time.”

It may seem challenging to practice social connection while maintaining physical distance, but Aldrich said it can be as simple as calling a sick relative or leaving a note with your phone number and an offer to pick up groceries in an aging neighbor’s mailbox.

“You don’t have to join a special club or download an app,” he said. “Even a FaceTime call can make a person think, ‘At least someone is thinking about me,’ and that is a big deal.’”