Coronavirus Today: Double duty for day-care workers

Good evening. I’m Thuc Nhi Nguyen, and it’s Wednesday, Feb. 24. Here’s what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

The pandemic has turned living rooms into classrooms and parents into de facto teaching assistants. But for parents who can’t work at home, finding a substitute has been difficult. Leaving young, school-aged children to take online classes on their own or under the supervision of older siblings isn’t effective, especially since big brothers and sisters have their own classes to deal with. Grandparents may be available, but they’re not necessarily Zoom experts.

For many families, the solution has been to rely on day care. And that means early childhood educators are now juggling the difficult task of caring for infants, toddlers and preschoolers while also managing impromptu classrooms for older students, my colleague Sonja Sharp reports.

The increased workload is yet another example of the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on people of color. Unlike K-12 teachers, who are more than 60% white, the majority of early educators and day-care providers come from the communities of color hit hardest by the outbreak. About 17% also live in poverty, a figure that’s about six times higher than the poverty rate for K-12 teachers.

Turning a space that was intended for younger children into a classroom suitable for remote learning has been a financial burden for day-care and preschool workers involved. Although they’re collecting extra tuition for their new charges, it’s not nearly enough to cover needs like high-speed internet, classroom equipment and more food.

“The whole thing has been frustrating,” said Elisa Coburn, executive director of Un Mundo de Amigos Preschool in Long Beach, whose students all live at or below the poverty line. “The state had said, ‘You really can’t have kids who should be in kindergarten in your program,’ but in the next breath they said, ‘Don’t unenroll kids.’ For several months, we were not getting any funding for these students.”

Many of the older kids now getting dropped off at day care are children of essential workers who receive state subsidies for child care. This week, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that significantly increased state child-care funding, including $80 million in additional emergency vouchers for children of essential workers.

The parents and early educators thought they would be in this situation for only a few months after the pandemic closed public schools last March. There was hope that regular school would resume after spring break, then in August, then maybe November.

Now in Los Angeles, that wait could extend until at least April.

L.A. Unified School District officials are targeting April 9 as a possible date to reopen elementary schools, but Supt. Austin Beutner reiterated Tuesday that the crucial issue is access to enough vaccine to inoculate 25,000 district employees. Teachers say they won’t feel comfortable returning to in-person classes without that protection.

Studies have shown that young children are far less likely than teenagers or adults to spread the coronavirus, and with smaller groups in preschools and day cares, many families see them as a safer option than a return to in-person schooling. But early educators share the fears of K-12 teachers who are able to work from the safety of their homes.

“We have this huge weight on our shoulders,” said Tanya García, who manages a day care in Hollywood. “It’s good that we have more children, but at the same time, [we worry] is tomorrow going to be the day we get it?”

By the numbers

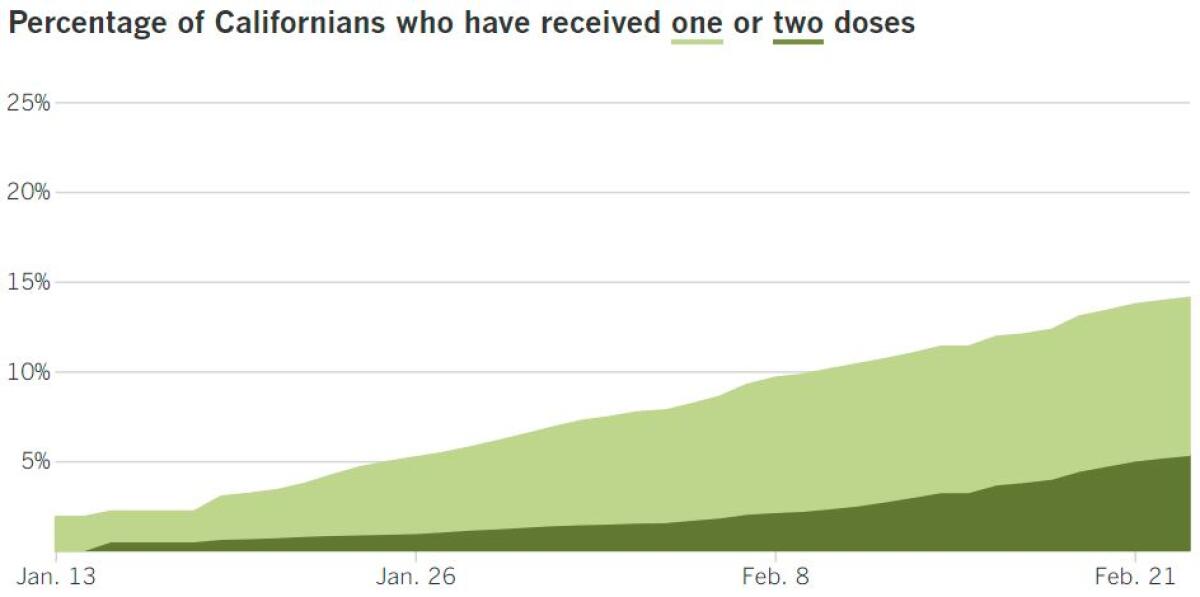

California cases, deaths and vaccinations as of 6:46 p.m. Wednesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Across California

California has surpassed 50,000 COVID-19 deaths, a tally that comes as L.A. County reported a backlog of more than 800 deaths over the autumn-and-winter surge. Daily coronavirus cases and COVID-19 deaths have dropped considerably in recent weeks, and the backlog — which mostly occurred in December and January — was discovered following extensive checks of death records, said Barbara Ferrer, the county’s public health director.

As the vaccine rollout continues, Newsom has said he wanted to examine the state’s distribution through “an equity lens.” Recent events — including The Times’ report of wealthy people who work from home misappropriating access codes intended for use by those in the communities hit hardest — have clouded the view.

Columnist Robin Abcarian suggests clearing things up by tapping into a system already in place: community health centers.

These clinics care for about 1.7 million poor people in L.A. County and already have locations in the precise neighborhoods the state wants to target. But the clinics haven’t played a large part in the distribution plan. Instead, officials have focused on mass vaccination sites that seem efficient but aren’t accessible to underserved people who don’t drive and can’t navigate the complicated online appointment system.

“We need to be seen as a network,” said Louise McCarthy, president and chief executive of the Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles County, which represents 64 nonprofit clinics with 350 sites. “Our patients will not be easy to reach with a mass vax site. We are trusted providers who can deliver the doses where they belong.”

McCarthy said her health centers could deliver more doses than the site at Cal State L.A, which is equipped to give out as many as 6,000 doses a day if enough supply is available. The location on L.A.’s Eastside was chosen to target communities who have suffered from the pandemic the most.

But shortening a commute doesn’t fix all the problems, McCarthy wrote in a letter to Newsom urging him to make better use of community health centers: “Just because there is a vaccination location geographically nearby does not necessarily mean it is accessible. Equity should not be forsaken for volume or expediency.”

At least one at-risk group in the state has been able to access the COVID-19 vaccine.

About 40% of incarcerated people in California’s corrections system have been immunized, my colleague Leila Miller reports. In a crowded environment where social distancing is difficult and staff come and go frequently, the vaccine is necessary to prevent the types of outbreaks that have killed as many as 211 inmates and 26 corrections staff members across the state.

“We’re pleased at the pace that they have been going at and have constantly been urging the governor to continue that pace,” said Sara Norman, managing attorney for the Berkeley-based Prison Law Office. “Correction facilities have proven to be deadly. Like nursing homes, they are on top of the list of the deadliest places to be in this country.”

The vaccines have been offered to patients at California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s skilled nursing facilities or in prison medical institutions. Almost 70% of incarcerated people who were offered the vaccine accepted it.

Grocery workers in L.A., who are in line to become eligible for the vaccine March 1, could soon get a hero pay bump of $5 an hour for the next 120 days now that the L.A. City Council approved the plan on Wednesday.

Seattle, Oakland, San Jose, Long Beach and unincorporated Los Angeles County have passed similar mandates to support grocery store workers who have been deemed essential since the early days of the pandemic, when stockpiling shoppers left shelves bare of flour, pasta, rice and toilet paper.

The L.A. ordinance, which also covers employees at drugstores, must return to the council next week for a procedural vote and will go into effect after it is signed by the mayor, who supports it.

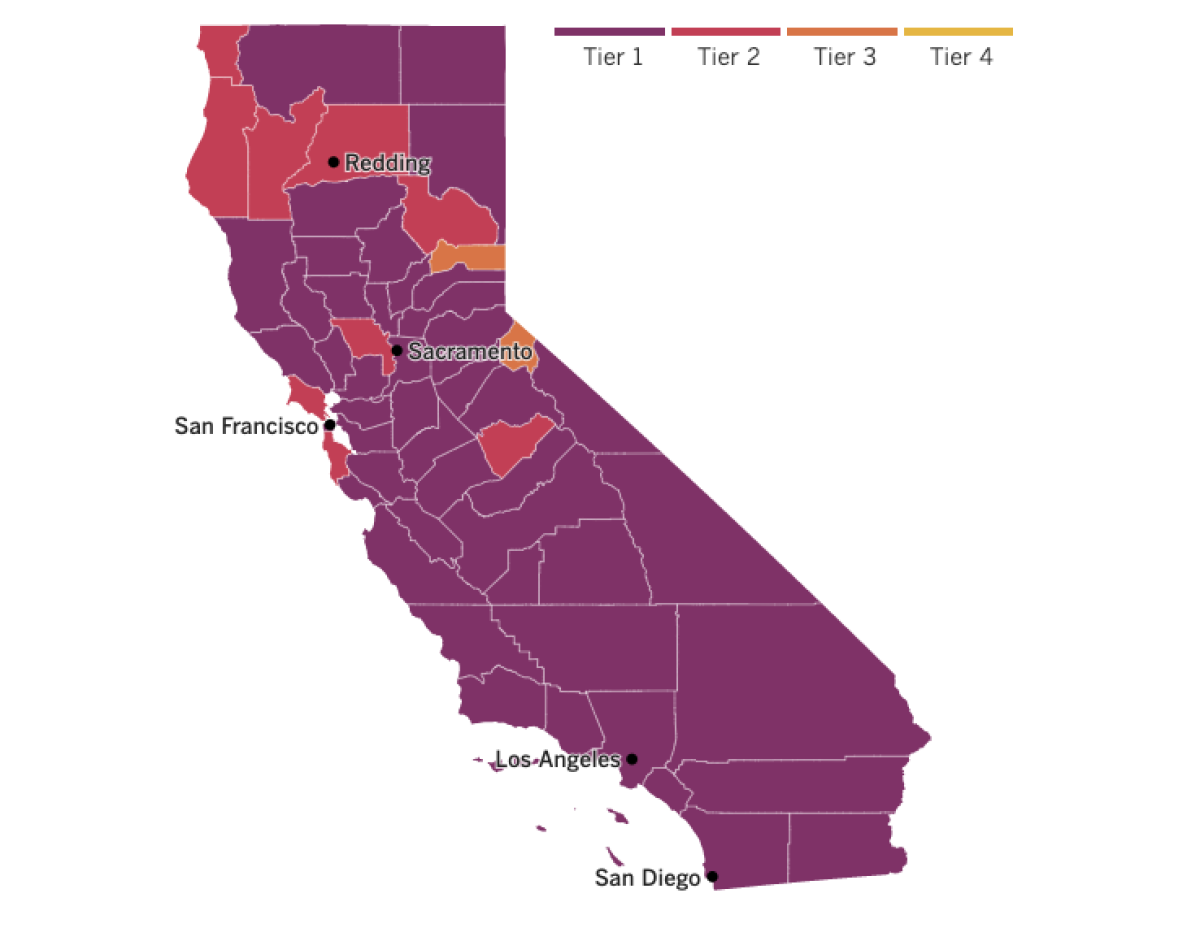

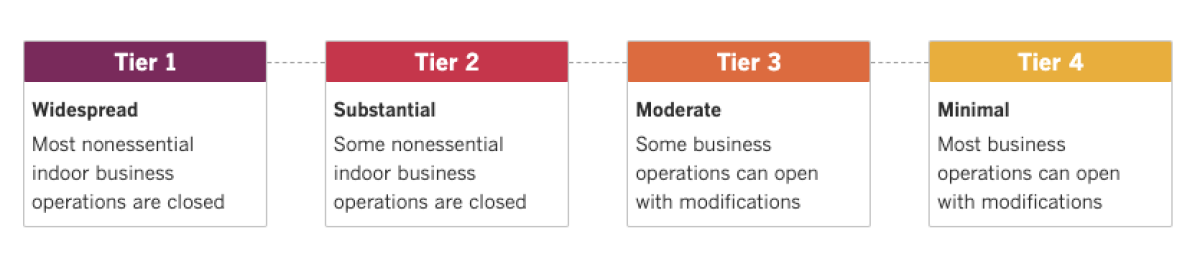

In Orange County, some high school sports can resume Friday after the county’s rate of new coronavirus infections dropped below the California Department of Public Health’s threshold of 14 cases per 100,000 people. Cases in Orange County dropped to 11.9 per 100,000 people, opening the door for high-contact outdoor sports like football, water polo and soccer.

See the latest on California’s coronavirus closures and reopenings, and the metrics that inform them, with our tracker.

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Around the nation and the world

The one-shot COVID-19 vaccine from Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen Biotech unit is safe and effective against severe cases of the disease, a review by scientists at the Food and Drug Administration concluded — a step that clears the way for emergency use authorization.

In an analysis released Wednesday, FDA scientists found that the single-dose J&J vaccine is 66% effective at preventing moderate to severe COVID-19 and about 85% effective at preventing the most serious illness. The results varied in different countries, with the best results in the United States, where the vaccine was 72% effective against moderate to severe COVID-19. That figure fell to 66% in Latin America and 57% in South Africa.

The numbers make the J&J vaccine seem like a downgrade compared to its Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna counterparts. Those shots, which are already authorized in the United States, were at least 94% effective at preventing COVID-19 in Phase 3 clinical trials conducted last year. But experts say a straight comparison of the numbers is not necessarily fair because all of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines have been tested under different conditions.

What makes the J&J shot appealing is that it’s easier to use and handle. Instead of requiring two shots delivered weeks apart like Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccines, J&J’s needs just one. It also doesn’t have to be stored at freezing temperatures and can last three months in a refrigerator. Regulators will soon decide whether the tradeoffs are worth it as the U.S. tries to tame the pandemic that’s already killed more than 500,000 Americans.

Many have wondered how the COVID-19 vaccines developed in record-breaking time would hold up in the real world. Now, my colleague Emily Baumgaertner reports on developments that could put some of those concerns to rest.

In a study involving more than half a million people who were vaccinated in Israel, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine remained nearly as effective after a nationwide rollout as it was during clinical trials. Israelis who received the shots were 94% less likely to become ill than those who hadn’t been vaccinated.

The results were published Wednesday in the New England Journal of Medicine. Josh Michaud, a global health expert at the Kaiser Family Foundation, called the study an “important milestone.”

“Up until now we’ve had to rely on scattered small-scale reports and non-peer reviewed findings for a glimpse of how effective COVID-19 vaccines are in the real world,” said Michaud, who was not involved in the study.

The vaccine was found to be 95% effective in clinical trials. But vaccine developers didn’t test for potentially disruptive factors, like a large winter storm that delays shipments across the country.

After studying more than 1 million people, researchers found that even one dose of the vaccine made the inoculated group 57% less likely to get sick and 74% less likely to be hospitalized than their counterparts in the non-immunized group. After the second dose, those figures rose to 94% and 87%.

The vaccine worked similarly well across all age groups, and the study’s authors said they were encouraged that the emergence of coronavirus variants did not seem to have a major impact on the effectiveness of the vaccine.

Israel is far ahead of most other countries in its vaccination campaign, with more than half the population inoculated. Ghana can now join the list of countries on that path, as 600,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine arrived there Wednesday.

The West African country became the first in the world to receive vaccines through the COVAX initiative. That United Nations-backed program geared toward providing vaccines to low- and middle-income countries hoped to start vaccinations at the same time as immunizations began in rich ones. But that plan was again foiled by supply problems. COVAX aims to deliver 2 billion shots this year but has legally binding agreements for only several hundred million shots.

Thus far, 80% of the 210 million doses administered worldwide were given in just 10 countries, World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said this week.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: How long should I wait to get vaccinated if I’ve recovered from a coronavirus infection?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention doesn’t offer a specific time frame for this, but because vaccine supply is low and the coronavirus antibodies your immune system made will protect you for several months, experts recommend delaying your vaccination in the interest of letting others who don’t have protection go first.

“We believe that when someone gets COVID and recovers, they’re protected and have antibodies for at least three months,” said Shira Shafir, an epidemiologist at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health. “Since we have such limited supply right now, we kind of want to take advantage of the fact that there are people who are already protected, and we can use those doses for people who are completely susceptible or completely at risk.”

The antibodies developed in response to an infection actually lead to immunity that’s comparable to that from a COVID-19 vaccine, at least for a few months, my colleague Amina Khan reports.

Researchers at the National Cancer Institute studied hundreds of thousands of Americans who previously tested positive for a SARS-CoV-2 infection and found that the risk of developing another infection more than three months later was about 90% lower than for people who had never been infected and thus had no antibodies to protect them.

To put that figure in perspective, the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines reduced the risk of developing COVID-19 by at least 94% in clinical trials.

The study, published Wednesday in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, didn’t gauge how long the immunity benefits of a prior infection last beyond 90 days. Other research suggests the protection could last a while, perhaps at least eight months.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.