Pandemic drives parents to put older kids in day care; providers ‘literally had to become teachers’

When public schools closed last March, Tanya García watched attendance at her busy Hollywood day care plunge. Some days, only one toddler came. But in recent months, Angelica’s Daycare has been busier than ever — particularly among school-aged students.

“Two of them came to our day care, and the mom was like, ‘They’re so far behind right now, please help them with their ABCs,’” García said. “We literally had to become teachers.”

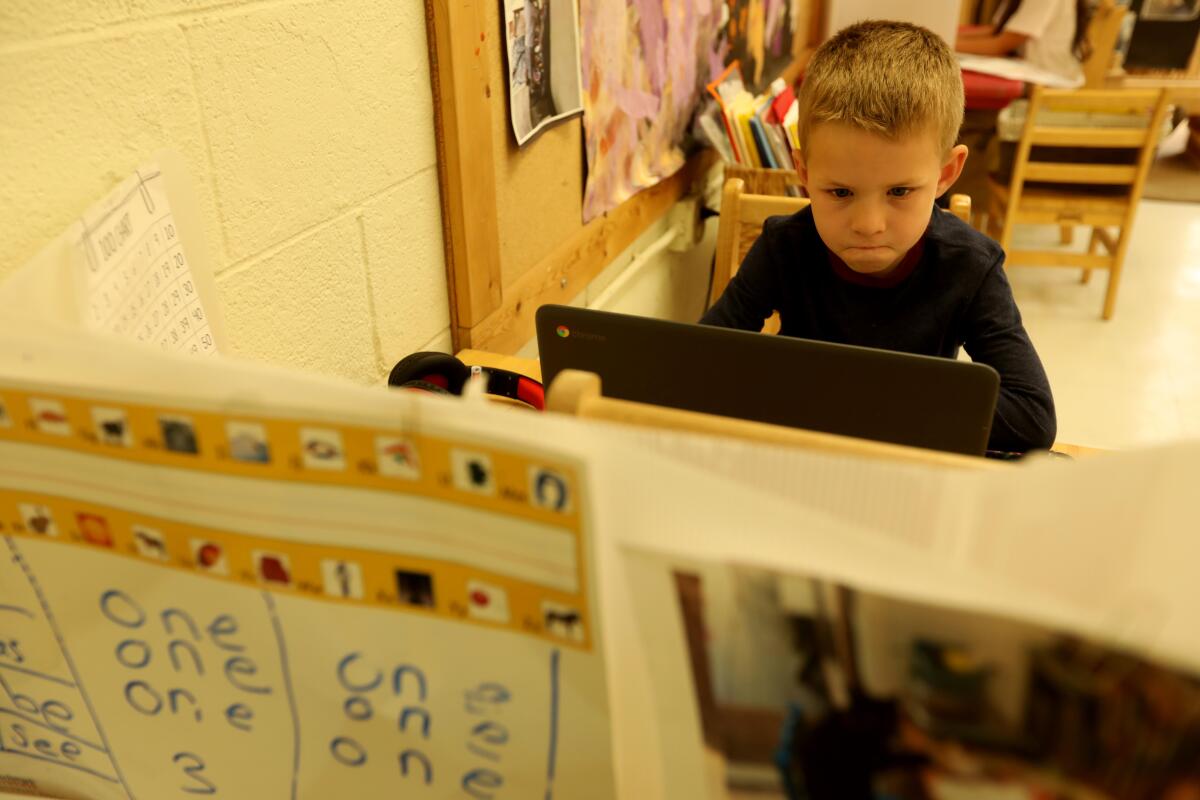

Indeed, preschool and day-care workers across the state say they have spent months managing ad hoc classrooms of older students — tutoring, troubleshooting and teaching supplementary material — while simultaneously caring for infants, toddlers and preschoolers. Officials could not say exactly how many of California’s 810,000 child-care seats were occupied by remote learners, but experts and educators say the numbers have surged.

“Child-care providers are taking on a lot of what normally happens in school, but they aren’t being supported,” said Keisha Nzewi, director of public policy at the California Child Care Resource and Referral Network. “Many people have been forced back to work outside of the home, so they have no choice — they need somewhere safe for their children to go.”

Experts say it’s yet another example of how the pandemic has taxed the already overburdened early care and education system in California. Unlike K-12 teachers, who are more than 60% white, the majority of early educators and day-care providers come from communities of color hardest hit by the pandemic. About 17% also live in poverty, about six times the poverty rate for K-12 teachers.

After months of delays and pandemic upheaval, officials have released the Master Plan for Early Learning and Care, a blueprint to remodel California’s Byzantine child-care system.

“When we look at the disparities between the early childhood system and its workforce and the K-12 system and its workforce, it’s quite stark,” said Lea Austin, executive director of UC Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. “In California, the majority of early care and education workforce are women of color, they’re in communities that are being disproportionately impacted by COVID, they are more at risk of hospitalization and death.”

According to a report released by the center on Tuesday, the average early educator in California makes less than half what kindergarten teachers do. The disparity isn’t new — elementary school teachers have long commanded higher salaries than early educators, in part because their jobs require more credentials. But many say the gap is made more glaring by the fact that day-care workers here have taken on thousands of kindergarten, elementary school and even middle school students since the start of the pandemic, while the majority of K-12 teachers work from home.

“Demand has been three times more than we’ve had at our highest peak [pre-pandemic],” said Jessica Chang, chief executive of WeeCare, the country’s largest home day-care network. “In school-age children, it’s at least a 30% increase.”

Most of these students are the children of essential workers, and tens of thousands of them receive state subsidies for their care. One referral agency, Pathways L.A., said 60% of its subsidized students were school-age children being looked after in day care. On Tuesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill that significantly increased state child-care funding, including $80 million in additional emergency vouchers for children of essential workers. Day-care workers are among those considered essential workers.

But the logistics of managing multiple remote students of different ages are very different than caring for infants or toddlers, and providers say they have had to spend more on things like high-speed internet, classroom equipment and even food for older children. Funding from the state has sometimes been slow in coming, and many say it hasn’t kept up with costs.

“The whole thing has been frustrating,” said Elisa Coburn, executive director of Un Mundo de Amigos Preschool in Long Beach, whose students all live at or below the poverty line. “The state had said, ‘You really can’t have kids who should be in kindergarten in your program,’ but in the next breath they said, ‘Don’t unenroll kids.’ For several months, we were not getting any funding for these students.”

Today, almost a third of the students at Un Mundo de Amigos are Long Beach Unified School District kindergarteners.

“You hear all these reports about poor struggling moms and dads who have their kids at home and they’re trying to work, but the bigger part of the story are the families that can’t work from home,” Coburn said. “Some of the families thought, ‘Let me let my child stay home with the older sibling or the grandmother,’ but they found their child wasn’t learning in that environment, because the older sibling doesn’t want to help, and the grandmother doesn’t speak the same language.”

Like parents, many providers believed public schools would reopen in August, or November, or after winter break. Now, many are coming to accept they will need alternative care for the rest of the school year.

“We thought it would be very temporary,” said Elke Miller, who runs Kigala Preschool in Santa Monica. “We did the first session until winter break, now the second until spring break. We’re just offering the third session until the end of the school year, because parents were hoping that schools would be opening, but obviously that’s not the case.”

Many families feel safer in preschools and day cares because the groups are smaller and many are home-based. But while young children are far less likely than teenagers or adults to spread COVID, providers still share the fears that have kept K-12 teachers out of the classroom since March.

It’s hard to predict what may happen when California’s primary schools reopen. But when it comes to the state’s youngest students, data are more robust and reassuring.

“There was a study that was released in October which showed child-care settings aren’t the source of community spread, but the women in those groups still experience COVID at higher rates,” said Nzewi, the policy expert. “Their family members have worked this whole time as well, which has led to greater risk of exposure, and then the families they care for are those same people who are working. So the whole little child-care bubble is at greater risk.”

The fear is particularly acute for those like García, who care for children in their homes.

“We have this huge weight on our shoulders,” García said. “It’s good that we have more children, but at the same time, [we worry] is tomorrow going to be the day we get it?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.