Young voters turned out in force for Democrats in 2020. Will they stick around?

Kip Lund was a detached spectator of politics in early 2020, more focused on his bioengineering job in San Diego than on presidential campaign hubbub.

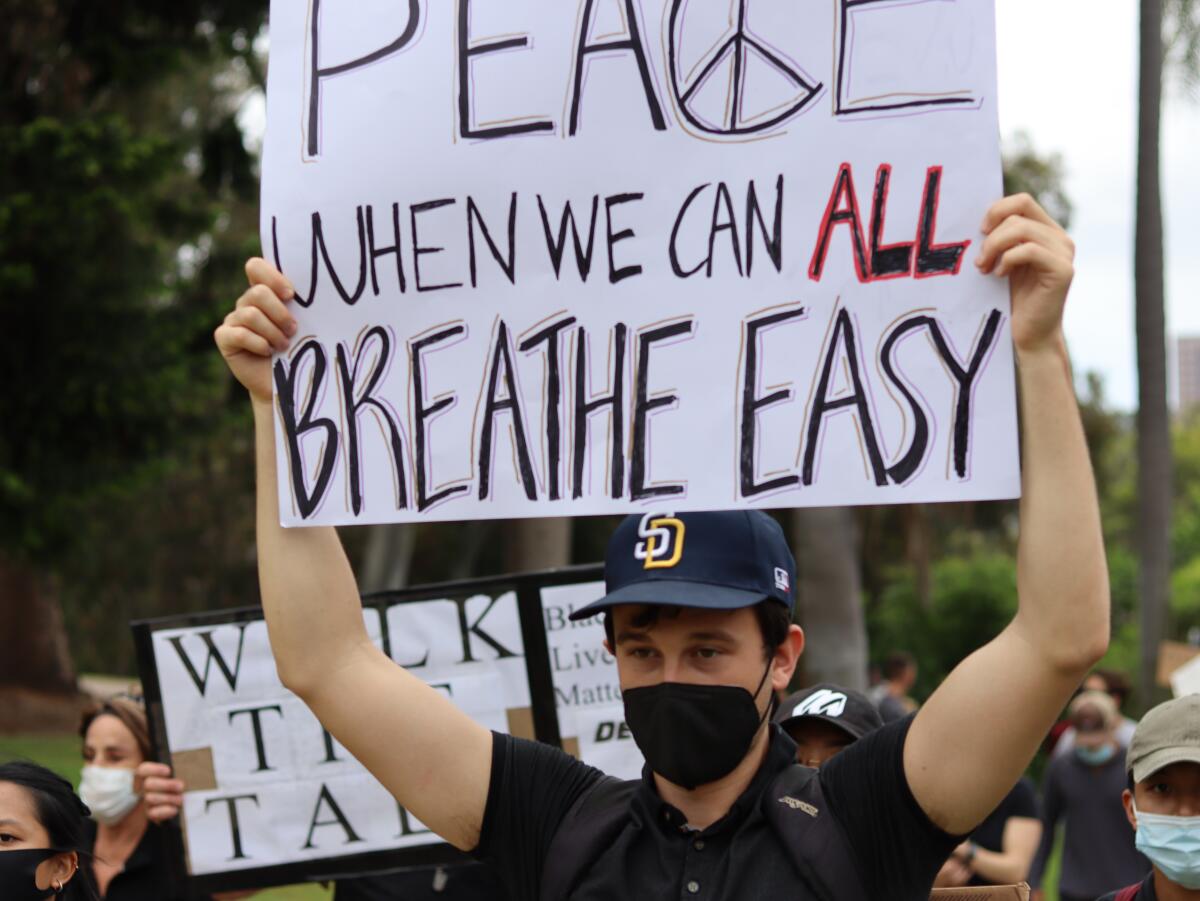

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Lund, like millions, had to work from home. With more time to reflect on civic affairs, he was swept up in the national reaction to George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police and joined his first big political demonstration. He voted for Joe Biden for president even though the Democratic nominee did not excite him. He became a volunteer with the Sunrise Movement, a youth-led climate change and social justice group.

“It was like a powder keg spark,” Lund, 27, said of his rapid journey from the sidelines to the front lines of political activism. “Being a part of those protests and feeling part of that energy and commitment in the streets in those numbers inspired me to pursue activism.”

Lund is part of a rising generation of young people who helped elect Biden in 2020 even though many were lukewarm about his candidacy, and who will be key to the Democratic Party’s ability to keep control of Congress in 2022. Many young people were spurred to vote by anger toward former President Trump, but much more is driving them.

These young Democratic voters have produced a new wave of grass-roots activism, inspired less by candidates than by their passion for issues that their generation thrust to the fore such as racial justice, gun safety and climate change.

“I’ve never seen the activism I’ve seen among young people,” said Luis Sánchez, executive director of Power California, a political group that organizes young people of color. “This growing awareness and civic engagement is engagement that goes beyond voting.”

A survey of young people by the Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics in March found 36% said they were politically active or engaged — even higher than the 24% who said they were engaged after President Obama’s 2008 election. The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University found in a 2020 poll that 31% of people ages 18 to 24 had participated in a march or demonstration, up from 5% in 2016. They didn’t just march; they voted. The 2020 surge of young voters — turning out at an even higher rate and in larger numbers than for Obama in 2008 — overwhelmingly favored Democrats.

Early voting is shattering records. Turnout may set a record. Campaigns can’t keep up with demand for yard signs. A great awakening has hit voters.

A big question for Democrats as they head into the midterm campaign is whether progressive young people will lose interest in politics in the post-Trump era, or become disillusioned with Democrats if they do not deliver on the issues they care about. Without them, it will be hard for Democrats to win their uphill fight to keep control of Congress.

Interviews with dozens of young Democratic voters, analysts and activists across the country show that multiple factors were behind the surge of youth political engagement over the last few years:

The desire to oust Trump was strong. States made it much easier to vote in the pandemic. The murder of Floyd and the deaths of others like Breonna Taylor at the hands of police drew more young people — stuck at home because of COVID-19 — out to protests. Evidence of climate change grew, and so did groups like the Sunrise Movement. A youth-led gun safety movement blossomed after the 2018 mass shooting at a Parkland, Fla., high school. The #MeToo movement galvanized women.

Some of those factors are now fading, causing Democrats to worry that turnout of young voters will drop as it usually does in a midterm election. Trump is no longer center stage. Many states are rolling back liberalized voting rules. The pandemic lockdown has begun to ease.

The Power of Youth

This is the second story of a three-part series on the effect of millennial and Generation Z voters on the Democratic Party, President Biden and the GOP.

Read the rest of the series:

Biden is the oldest president in American history. Here’s how he aims to bridge a canyon-sized generation gap

But one big factor is unchanged: The issues that brought many progressive young people into politics remain pressing and unresolved. Today’s issue-driven youth movement could prove more durable than the youth-vote boom that propelled Obama’s rise, a more candidate-focused movement for change that lost steam by the end of his presidency.

“Their activism may endure because it’s come not out of attachment to Biden but from issues that are not going away,” said Simon Rosenberg, a Democratic political strategist.

That may be especially true for young voters who were inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement. “That is one of the most important motivations for young voters,” said Jasmine Burney-Clark, founder of Equal Ground Education Fund and Action Fund, a Black-led voter mobilization group in Florida. “We have to be very honest, Biden was not the No. 1 pick for a number of younger Black voters looking for someone more progressive. “

Young voters may not have loved Biden, but their ballots were crucial to his victory. In narrowly won states such as Georgia, Arizona and Pennsylvania, Biden won young voters by margins that helped tip the balance in his favor, according to the Tufts civic learning center.

Democrats’ advantage among young voters is of relatively recent vintage. Before most millennials qualified to vote — in the 2000 presidential election and most elections back to 1972 — young voters split about evenly between the parties. That changed in 2004, when Democrat John Kerry won 54% of the youth vote. Since then, Democrats’ edge has grown.

That is partly a reflection of a demographic shift over the last 20 years. Voters younger than 40 are the most racially and ethnically diverse generations in American history: About 45% of millennials (people born between 1981 and 1996) and nearly half of Gen Zers (born after 1996) are people of color, compared with 30% of baby boomers.

This points to a big problem for Republicans, who have struggled to attract younger Black, Latino and Asian American voters as millennials and Gen Zers have come to dominate the voting-eligible population. Republicans have not given up the fight for their votes. One-third of voters younger than 30 cast ballots for Trump in 2020. College Republicans are still organizing on campus. Turning Point USA, a youth conservative group, has drawn thousands to organizing conferences that headline A-list GOP leaders. But when Trump ran for reelection in 2020, he lost under-30 voters to Biden by 24 percentage points.

Though Republicans are trying to make gains among young voters, they are not the fundamental pillar of the party’s coalition that they are for Democrats. Yet when it comes to mobilizing voters, even the Democratic Party has usually given short shrift to young people, focusing more on older voters who are more inclined to vote.

“I do not believe that Democrats have centered enough young voters in their strategy, as part of the voice of the party, or understand the political potential and transformative power of young people in this country,” said Cristina Tzintzún Ramirez, who in March became executive director of NextGen America, the largest political group focused on organizing young people. Ramirez, who spent years as a political organizer in Texas, is pushing for the group to reach further beyond college campuses to organize more people of color, older millennials and people without college degrees.

An early test of young voters’ political engagement comes this year in Virginia, which has a competitive gubernatorial election. Carissa Kochan, a University of Virginia student involved in Democrats’ campus chapter, said she is girding to fight a wave of student indifference.

“The Trump era gave us major momentum,” said Kochan, who braved sweltering heat one August day to hear from Democrats’ gubernatorial candidate, Terry McAuliffe. “I’m a little bit worried about maintaining that momentum in 2021. But I’m hoping that we saw what can happen when we start paying attention.”

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

For young voters, the pandemic has been just the latest in a series of life challenges thrown at their generation. Older millennials entered the workforce amid the Great Recession. School shootings became shockingly commonplace over the last 20 years. Young people — especially people of color — were hit hard by the pandemic and its economic effects.

Evan Holt, a 33-year-old who did not finish college but is now running for Cincinnati City Council, says many of his peers suffer from having been under tremendous pressure to go to college, resulting in mountains of debt far greater than what previous generations shouldered.

“We were straight up told that if we didn’t go to college we’d be flipping burgers,” Holt said. “My friends with degrees are poor.”

Ironically, the pandemic may have helped facilitate higher levels of political engagement among young people. The ways states tried to limit the virus’ spread by making it easier to vote were especially useful for first-time voters who are often baffled by registration and ballot processes.

That could change in 2022, because many new state voting laws are repealing the pandemic-era changes and implementing other provisions — such as stricter voter ID and residency requirements — that will make it harder for young people to register in college towns. Rock the Vote, a group focused on getting young Americans to the polls, is stepping up its education efforts on how to navigate these new requirements.

In Georgia, the group is teaming up with professional sports teams and celebrities to promote voter education in Atlanta’s high schools, sponsoring a curriculum designed to inform teenagers even before they are old enough to vote.

The pandemic shutdown also proved to be an incubator of political activism and ambition.

“Young people really took advantage of their time and used the internet as a medium for spreading activism,” said Osirus Polachart, a 23-year-old student at UC Berkeley. Those efforts did not end just because Trump left the White House.

Early this year, Polachart and other students across California formed Project Super Bloom, an organization to get more young people elected to office. The group helped elect the second-youngest member of the California Assembly, 29-year-old Isaac Bryan.

Malcolm Kenyatta, a 31-year-old Democrat running for U.S. Senate in Pennsylvania, said he believes his youth would be a big asset in an institution that now includes just one member younger than 40.

“It matters tremendously that we have a government that looks like the people they want to serve,” Kenyatta said. “We have more octogenarians than we do millennials in the Senate.”

Run for Something, a group that recruits and supports young progressive candidates for state and local office, sees no sign of waning interest in the post-Trump era. To the contrary, the 15,000 people who have already come to the group with interest in running for office this year exceed the group’s recruitment numbers in past years, and that figure is on pace to beat 2020.

Among the newly activated: Chi Ossé, a 23-year-old who lost his restaurant job during the pandemic, said he had not considered running for office until he got involved in Black Lives Matter protests after Floyd’s murder. He decided to run for New York City Council, faced a field of Democratic rivals who tried to make an issue of his youth, and won the primary — tantamount to winning the general election in his Democratic-dominated district.

“I started to find my voice,” Ossé said. “Something deep inside me said that marching and shouting is not the only strategy we should use.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.