Why the coronavirus crisis is another cruel economic setback for millennials

SAN FRANCISCO — Nick Andersen packed up his life in Charleston, S.C., and headed south for a new job and a new start. On March 1, he signed a one-year lease on an apartment in Miami.

Within two weeks of taking up his position at a financial software company, he was working from home. A month later, he wasn’t working at all.

“It was a Monday night,” he says, describing a routine familiar to many of the more than 40 million Americans unemployed or furloughed during the coronavirus crisis. “I got an email for a Zoom meeting the next morning.”

The bosses who had eagerly welcomed Andersen, 32, to the company just weeks earlier were now telling him he was being placed on “indefinite furlough.” He would not be paid, but he at least kept his health insurance.

His initial unemployment claim took weeks “and weeks!” to be processed. It was rejected, a letter explained, because of his lack of employment history in the state of Florida, where he now lived.

He cashed out his savings account: around $10,000. It was money he had been excited to have built up over the last few years, achieving what felt like financial stability. Now it would have to be used to make ends meet.

“It’s just kind of like … the millennial story,” he says. “We keep working for this future that’s not really coming.”

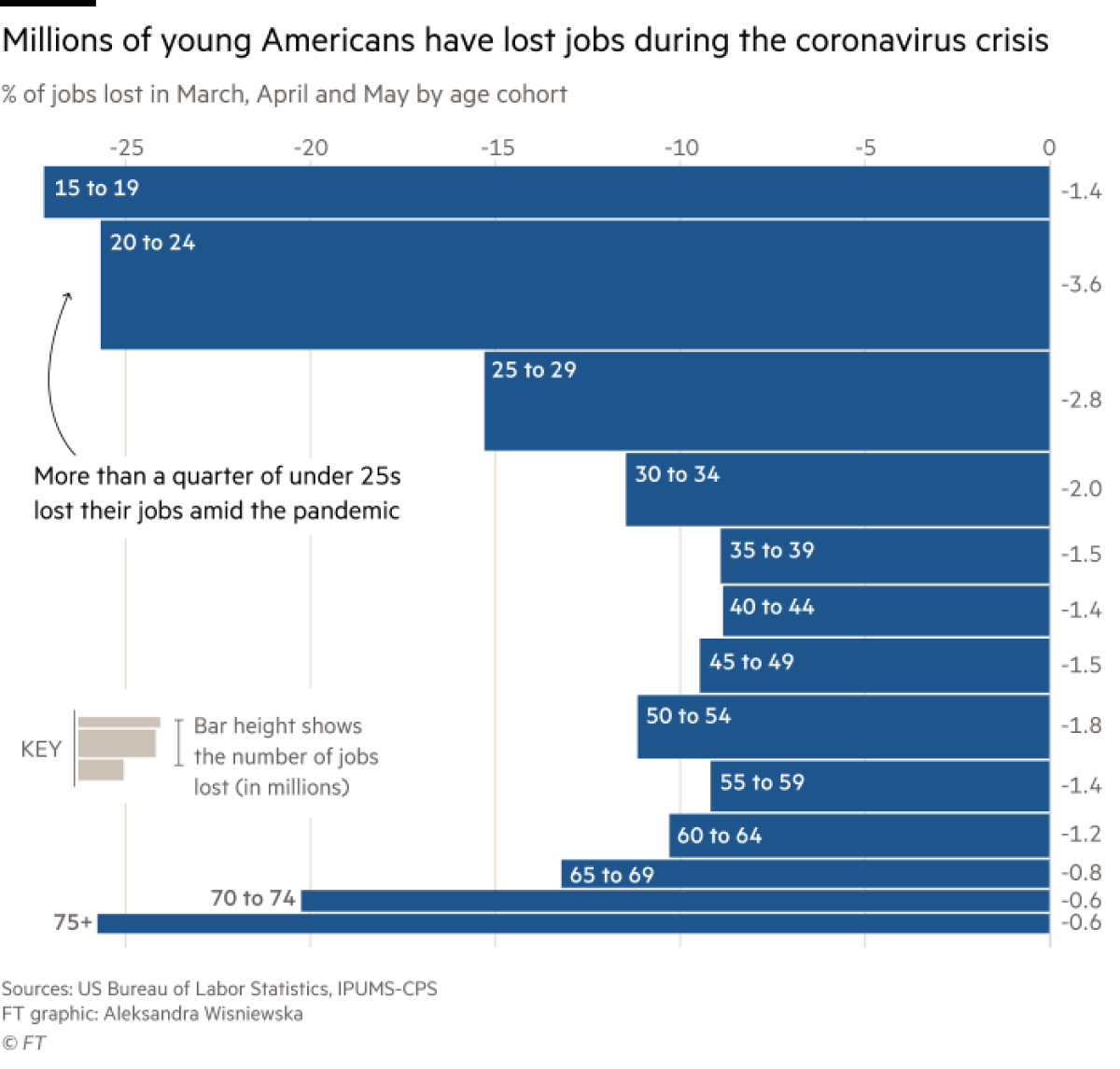

Few events have exposed such a sharp generational divide as the pandemic. Despite all the mysteries surrounding the virus, one of the few certainties is that people over 70 are much more vulnerable to the disease it causes, COVID-19. Yet, amid the economic onslaught that the coronavirus has wrought, it is those younger than 40 who have suffered the biggest economic blow.

In effect, the young feel they have had their lives upended in order to save as many of the old as possible.

As governments begin to plot a path out of the crisis, generational redistribution is likely to become one of the dominant political themes. Having now watched them suffer two economic cataclysms in just over a decade, there will be strong pressure for older generations to repay the favor and help millennials get back on their feet.

According to Ana Hernández Kent, a policy analyst at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, many millennials in the U.S. should be entering their peak earning years. Instead, the combination of the 2008 financial crisis and the coronavirus is a “double blow” that could amount to a devastating setback.

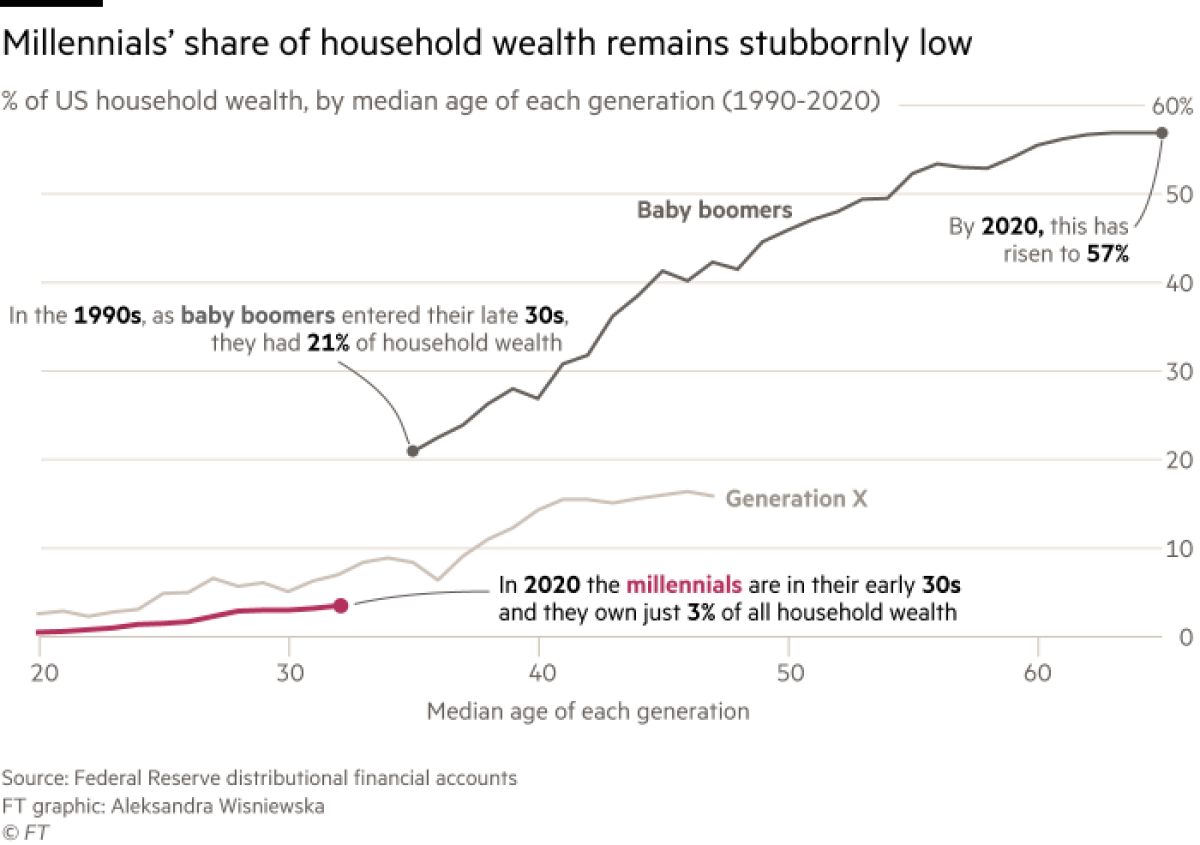

“That Great Recession has really followed them for the past decade or so,” she says. “Even as of the fourth quarter of 2019, millennials were still below, in terms of wealth, where we would expect them to be based on older generations at similar ages.”

The financial crisis shaped the views of millennials in ways that are already driving politics on both sides of the Atlantic, including the greater willingness of younger people to refer to themselves as socialists. Millennials elevated Jeremy Corbyn to the leadership of the Labor Party and Bernie Sanders to the verge of the Democratic presidential nomination. The coronavirus outbreak is likely to sharpen many of these views.

For many millennials, the social contract did not work for them, even before this latest crisis. Edward Glaeser, an economics professor at Harvard, says millennials in the U.S. look at the free healthcare for seniors under Medicare and tax breaks on mortgages and see a form of “boomer socialism” that excludes them.

“America has not done a good job of protecting or empowering its younger citizens,” he says. For the last 50 years, politics ended up protecting the privileges enjoyed by “insiders.” “It’s the young who have borne the brunt of that, even before this current crisis.”

Low-wage scars

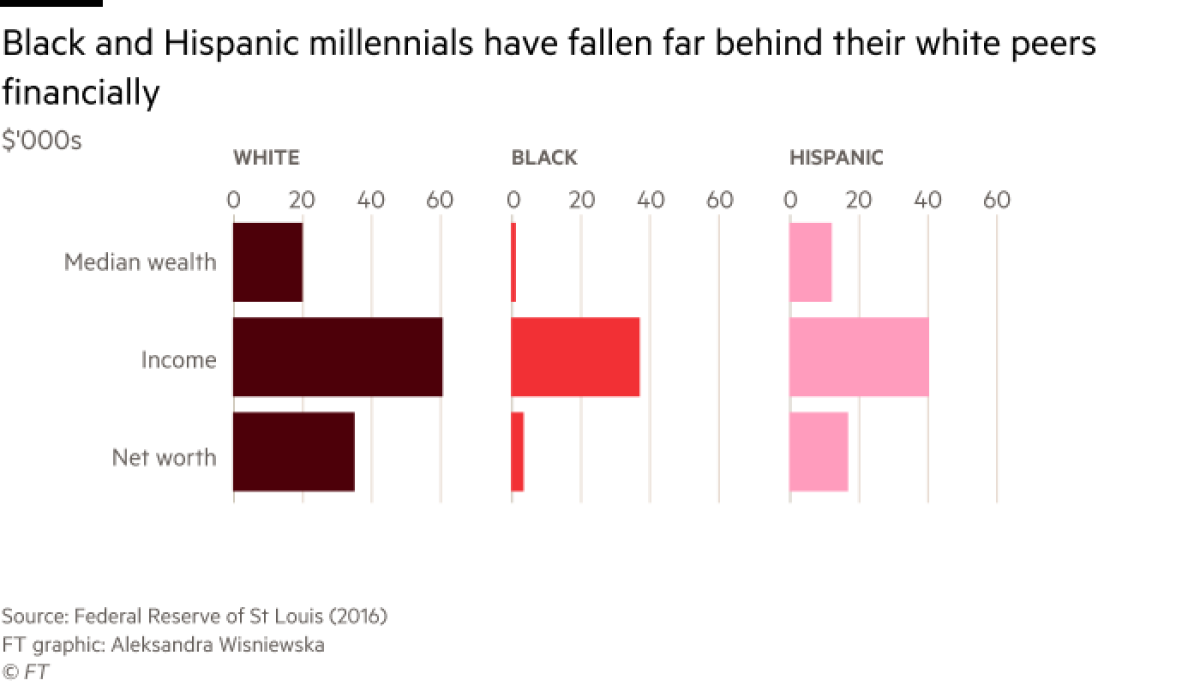

Definitions vary, but Pew Research considers anyone born between 1981 and 1996 to be a millennial, which means the oldest millennials are 39 years old today, and the youngest 24. In the U.S., this generation is the most diverse in the country’s history, the first that is not majority white, which makes sweeping generalizations about their prospects unwise.

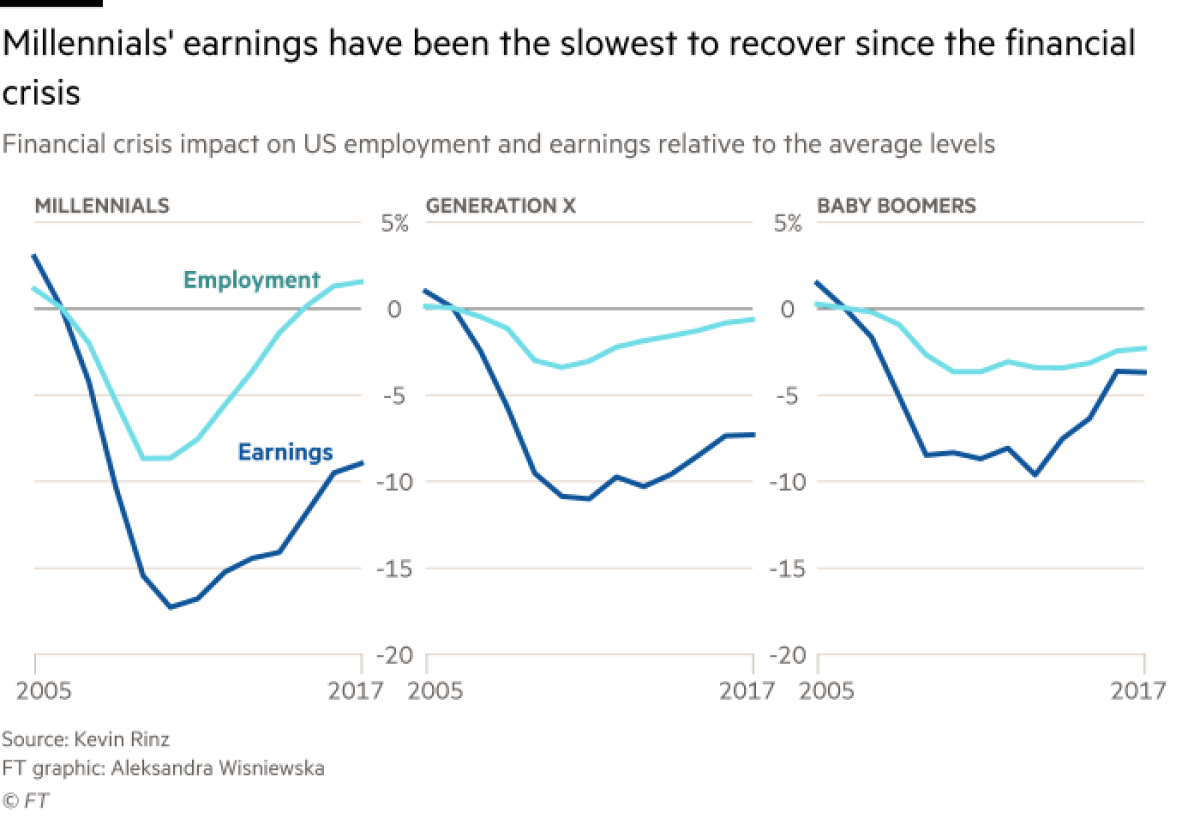

But the one thing that unites many of the older millennials in facing this new recession: They have not yet recovered from the last one.

Graduating into a recession makes it hard enough just to find a job. But it can also leave what economists calls “wage scars,” where the lower starting rate of pay stays with you throughout your career.

According to Carnegie Mellon University economist Shu Lin Wee, limited career mobility after the financial crisis meant that millennials were caught between two wholly unsavory choices: stay in jobs where they were being underpaid due to lackluster salaries set at a time of high unemployment, or change career path into areas where a lack of experience means starting out further down the ladder. Shu says the wage scars of a recession could drag on a person’s income for up to 20 years.

Kent’s analysis presents a similar conclusion. Even before the coronavirus, she calculates that the typical older millennial family’s median wealth — what they own minus what they owe — was around a third lower than where they should be compared with previous generations at the same stage of life.

Many of those trends are now likely to be exacerbated by the coronavirus crisis. Millennials of all races are more likely to be on short-term, temporary or zero-hours contracts — the sorts of jobs in restaurants, cafes or the gig economy which have been most vulnerable to being cut during lockdown. The same is true for the members of Generation Z, the cohort younger than millennials, who have already entered the workforce.

For the first time, nonwhites and Hispanics were a majority of people under age 16 in 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The St. Louis Fed estimates as many as 16% of U.S. millennials do not have the immediate means to cover an emergency expense of $400. For Black millennials in particular, that figure rises to 32%.

“Talking about millennials as a whole group oftentimes gets headlines because it’s easy to wrap your mind around,” says Kent. “But it’s the subgroups — minorities, Blacks and Hispanics, particularly women — that are really struggling.”

The pandemic has brought many of these disparities into sharp relief.

“You have this idea in your head of how it’s going to go,” says Erica, 33. “I’m going to go to college, then grad school, and then I’m going to buy a home.”

But achieving the first two of those three things has left Erica, who asked not to use her surname, with student debts of $106,000.

Erica was one of the first in her African American family to go to college. She graduated in 2008, into the recession, and is now also feeling the economic effects of the coronavirus. As well as her own debt, her parents took out additional loans to help cover her college costs, money which Erica is paying back on her own since her father lost his job at a manufacturing plant shut down as a result of COVID-19.

“Every single penny goes towards these loans,” Erica says.

She lives and works in Oakland at a nonprofit organization, partly because doing so makes her eligible for a federal student loan forgiveness program. It means she should see her debts removed after 10 years’ worth of payments, six of which are already behind her. But recent headlines about people unable to claim forgiveness on their debts due to an assortment of controversial technicalities has made her nervous.

“I don’t even allow myself to dream about that day,” she says.

She criticizes the predatory tactics used to tie down students from lower-income families, who may have had limited financial literacy, with high-interest loans on the promise it would mean more opportunity in life.

“People just handed out money,” Erica says, “and then stripped those young people of every single penny that they were able to attain from that degree.”

Successful Black millennials, she says, also face cultural pressures that are often more difficult to measure but have a continued effect on the accumulation of wealth.

“A lot of times, when you’re from a Black American family, oftentimes you become the person who is serving as the pocketbook for the family,” she says. “A lot of resources go into taking care of family members, cousins, close friends from childhood. My white peers don’t usually have that same obligation.”

According to research from the St. Louis Fed, 1 in 5 Black millennials provide regular financial support to someone outside their own immediate household, for example, compared with 8% of white millennials.

Avocado toast (and other consumption myths)

In 2017, Tim Gurner unwittingly turned himself into a viral hate figure for a generation. In a TV interview, the Australian property developer suggested it was not economic hardship that was keeping millennials off the housing ladder but a flamboyant taste in brunch.

“When I was trying to buy my first home,” said Gurner, who got his start thanks to a loan from his grandfather, “I wasn’t buying smashed avocado for $19 and four coffees at $4 each.”

In the real world, there is little evidence to support the “avocado toast fallacy” or variations on the theme. But Gurner perhaps tapped into a sentiment common among older generations — or in his case, the more privileged millennials — that a lack of economic success has been down to certain personality traits of an overly pampered group.

Gray Kimbrough, an economist from American University, argues that a series of myths has developed to explain the economic travails of millennials.

“The biggest myth that I’ve spent a lot of time attempting to debunk is that millennials are job hoppers,” he says. “It’s one that refuses to die.”

In fact, millennials actually switch jobs a lot less often than previous generations at the same stage of their careers.

Kimbrough cites several reasons for this, such as the U.S. healthcare system, where coverage for workers and their families is often tied to their current place of employment, a big disincentive to leave.

When it comes to predicting future real estate prices, the crystal ball is cloudy.

The persistence of such myths has prompted its own generational resentment. The “OK boomer” insult, which rapidly spread across the internet last year, was enthusiastically co-opted by millennials who felt let down by older generations.

“I see the whole ‘OK boomer’ thing as being about power,” says Kimbrough who, at 38, is a millennial — just.

“We hear, ‘Well, when I was your age I put myself through college and I bought a house downtown, raised you on one salary.’ But [boomers] have put in place these power structures that make it impossible for me to do that. I think that’s what ‘OK boomer’ was really about.”

Political alienation

The feeling that society is rigged against them helps explain the sharply leftward shift in views among many millennials in the U.S. In a poll conducted last year by Harris, 49.6% of Americans born after 1981 said they would prefer to live in a socialist country. A Harvard poll of Americans under 30 has seen a sharp increase in support over the past eight years for the idea that healthcare is a basic right that the government should have a role in providing: In the poll this year, 63% agreed.

It was this sort of sentiment that looked at one stage as if it would propel Sanders, the Vermont senator, to be the first self-described socialist to win the Democratic presidential primaries. Boosted by a support base of loyal millennials, Sanders offered a clear message: that the sort of assistance from the state that is offered to seniors should also be extended the young.

Sanders may not have secured the nomination, but political analysts believe that the eventual winner, Joe Biden, will need to find a way to mobilize some of that enthusiasm if he is to convince millennials to turn up at the polls in November, starting with his choice of vice-presidential candidate.

“If Joe Biden is looking to get everybody in his base fired up, what he should do is look for somebody who inspires the young,” says Perry Bacon Jr., from opinion poll and analysis site FiveThirtyEight.

The issue that polls say is most likely to give millennials something to get truly excited about is expanding student debt forgiveness.

In their lifetime, millennials have seen the cost of a college degree rise rapidly — almost 70% since the turn of the millennium. Around $1 trillion of the more than $1.5 trillion overall student debt has been added since 2005. And while reliable data broken down by age is limited, estimates suggest the average millennial student debt is more than $30,000. The Harvard poll found that 85% of young Americans favor some measure of reform to the student loan program.

“College was supposed to be the ticket to financial security,” says Jesse Barba, from Young Invincibles, a nonprofit advocacy group. “The root cause of people not being able to start their careers or start a family is this mountain of debt holding them back.”

The other big barrier to wealth creation is the cost of property — a complaint of millennials in big cities around the world as 10 years of low interest rates has helped to drive prices ever higher. From Berkeley to London, the high price of property is reviving debates about rent controls — a policy that had been considered taboo in many places for a generation.

Reid Cramer, a senior fellow at the New America think tank, suggests the path to home ownership should be made more flexible, with options such as “shared-equity housing, co-operatives and options other than private, single-family homes.” Housing providers, particularly nonprofit groups, should be aided to increase supply.

Some young people complain that the schemes that do encourage home ownership do not take into account the cost of student debt.

“The restrictions are insane,” says Erica in Oakland. “So many of the programs exclude us because we make too much money — but there’s no taking into account the debts that people are carrying.”

Glaeser says there is a palpable mood of discontent among young Americans at the status quo, motivated by both the coronavirus and racial injustice, but that the long-term effects will depend on whether demonstrators coalesce around realistic policy proposals.

“The pandemic helps engender anger,” he says. “But it doesn’t naturally lead towards clear thinking and effective, durable political change.”

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.