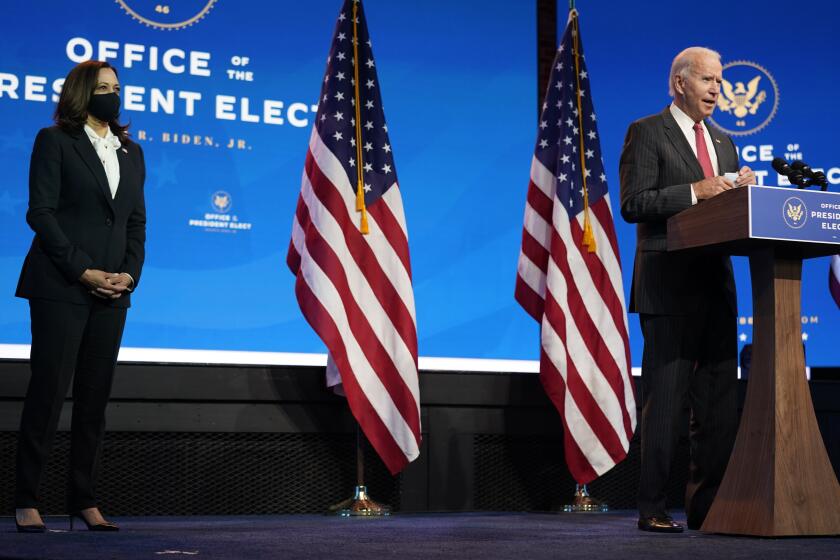

Harris was a partisan in the Senate. Now she and Biden need Republican friends

- During four years in the Senate, Vice President-elect Kamala Harris used high-profile, partisan moments to propel her political career, grilling President Trump’s Cabinet secretaries over hard-line immigration policies and Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh over abortion rights and sexual assault allegations ahead of his 2018 confirmation.

WASHINGTON — But as she and President-elect Joe Biden prepare to take office next month, their ability to bridge such rifts with Senate Republicans will determine whether they can pass much of their agenda — not least, bold policies to expand healthcare access, revitalize the economy and combat climate change — and get approval of Biden’s appointees.

While Democrats have a majority in the House, Republicans will either retain control of the Senate with as many as 52 votes or form a potent 50-member minority, depending on the results of two Jan. 5 runoff elections in Georgia. Biden and Harris will almost certainly need support from at least some Republican senators to win any votes — a tall order.

Biden speaks at almost every turn about his four decades in the Senate, and the bipartisan achievements in that time, but it is Harris’ recent, especially divisive experience that is arguably more relevant to their prospects for legislative bonhomie.

Since Biden left in 2009 to become vice president, the body where even fierce partisans often came together to make deals has devolved into a place so polarized that passing just about any significant legislation is rare. Biden overlapped with only a third of the current members.

With little chance to work on important bills and more power concentrated in the hands of Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), many senators have calculated — like Harris — that they can achieve more by playing an outside game: using their platform to please their political base rather than to forge bipartisan alliances to cut deals.

As veep, Kamala Harris will have every opportunity for clout. Biden, the oldest man to become president, has promised her a prime role. But she faces minefields too.

“Reaching across the aisle used to get you plaudits in a campaign,” said Jeff Flake, a former Republican senator from Arizona. “Now it just gets you a primary.”

Flake, who declined to seek reelection in 2018 amid the party backlash after he broke with Trump, said he had few interactions with Harris, though he served on the Judiciary Committee with her for two years and was one of the few Republicans inclined to negotiate with Democrats. The committee, which was the platform for many of Harris’ most viral moments, is among the most polarized in the Senate — not conducive to fostering bonds among senators from opposite parties, Flake said.

Though Biden ran for president on the promise that he could restore a sense of bipartisan comity, most Senate Republicans — including McConnell — refused even to acknowledge his victory for more than a month after the election. And they remained silent or even complicit as President Trump stoked false claims that he was the rightful winner, encouraging a majority of Republican voters to doubt Biden’s legitimacy.

Biden has indicated that he is eager to take a large role in negotiating with the Senate once he is sworn in, given his past relationships with its most senior members. Yet McConnell, with whom Biden overlapped for a quarter-century, spoke with the president-elect for the first time on Tuesday, when Biden called him to thank McConnell for his belated congratulatory remarks that day in the Senate.

Biden has said Harris will be a governing partner, a role he had under President Obama. Yet in Senate negotiations, Biden often took the lead; Obama, like Harris, had spent less than one term there and did not develop many relationships. Vice President Mike Pence, a former House member, has at times been Trump’s liaison to senators, but, with their party in control, the role has been less critical. Harris’ exact role in the Senate, where the vice president is the body’s titular president but mainly serves as a tie-breaker, has not been made clear and could well depend on the issue.

Harris can perhaps be most valuable to Biden in providing a fresher eye on the Senate. “It is probably important for him to have that kind of firsthand experience about the ‘new Senate’ inside the White House,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.).

Harris is generally well liked on both sides in the Senate. But she has no significant legislation to her name, and interviews with senators and aides suggest that Harris’ time in the Senate did not buy her much goodwill among Republicans.

She is not known to have any substantive relationship with McConnell, who will determine whether the administration’s initiatives even get a vote if Republicans retain at least one of the Georgia Senate seats.

How might the broad perception that Joe Biden, at 78, will choose to be a one-term president hobble his effectiveness? Should he perhaps deny it?

“She’s someone who I think had aspirations for higher office to start with and probably wasn’t spending a lot of time in the Senate,” said Sen. John Thune (R-S.D.), McConnell’s top deputy.

“She wasn’t here very long,” Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas) said dismissively. “She’s a very pleasant person. But I’d be hard-pressed to think of — has she achieved any legislation since she’s been in the Senate?”

Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), who chaired the Senate Homeland Security Committee on which Harris served, offered similar sentiments, pointing to her politically charged turns questioning administration officials as her most memorable mark.

“She was like a prosecuting attorney, and I didn’t really work with her on anything,” Johnson said.

Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski, one of the few Republicans known for working across party lines, concurred. Murkowski instead noted that she had a long-standing relationship with Biden. “When I came in, Biden had been here for already 20 years prior to me,” she said.

In her political memoir, “The Truths We Hold,” Harris laments that lawmakers behave differently when the television cameras are turned off, pointing to her service on the Senate Intelligence Committee, where much of the work is classified and done behind closed doors.

“It is invigorating, even inspiring,” she wrote. “It is a scene I wish the American people could see, if just for a moment. It is a reminder that even in Washington, some things can be bigger than politics.”

But she notably mentions few of her Senate colleagues by name in the book, which was published in 2019, just before she announced she was running for the Democratic presidential nomination. She writes only fleetingly of what she called a friendship with Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.), whom she credits with crossing the aisle during a debate to discuss race — specifically, her view that race is the nation’s “Achilles’ heel,” and his that racial healing starts with breaking bread together.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Harris’ aides point to bills she worked on with Republican senators — one with Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul to encourage states to reduce cash bail requirements for people awaiting trial, and another with Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina to make lynching a federal crime. She also helped lead an effort to propose policing changes after the killing of George Floyd in late May, but bipartisan negotiations crumbled.

Tellingly, representatives for Lankford, Paul and Scott either declined requests for comment or did not respond.

One former Harris aide said Harris came to the Senate eager to court Republicans and did not give up, but learned quickly that such relationships matter little with McConnell, who coldly looks at everything through a political lens. He refused, for example, to let the Senate vote on the cash bail bill. The lynching bill was approved by the Senate but has not become law because it has not been reconciled with a different House-passed measure.

During Harris’ Senate career, Republicans controlled the White House and the Senate. McConnell made filling judicial vacancies his priority, and little legislation passed beyond what was needed to keep the government funded. The Republicans’ most substantive policy priorities were repealing Obama’s signature Affordable Care Act — an effort that failed — and passing a tax cuts package that become law in late 2017.

Harris, alongside other Democrats, opposed both efforts.

For signs of hope, her aides point to the congratulatory fist bumps that some Republicans gave Harris when she returned to the Senate after her election last month.

Covering Kamala Harris

But for many Democrats, the lasting impression was not the fist bumps, but Republicans’ weeks-long refusal to publicly acknowledge the victory, for fear of crossing Trump and their party’s base.

That behavior has provoked worries among Democrats that neither Biden nor Harris will find a way to cut deals.

“The sad reality is that relationships don’t matter anymore,” said Adam Jentleson, who was an aide to former Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid and is the author of a forthcoming book, “Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy.”

“The more important factors are the macro forces at work on senators,” he added. “And foremost among them is polarization.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.