On Biden’s to-do list: Blunt the talk that he enters the presidency as a lame duck

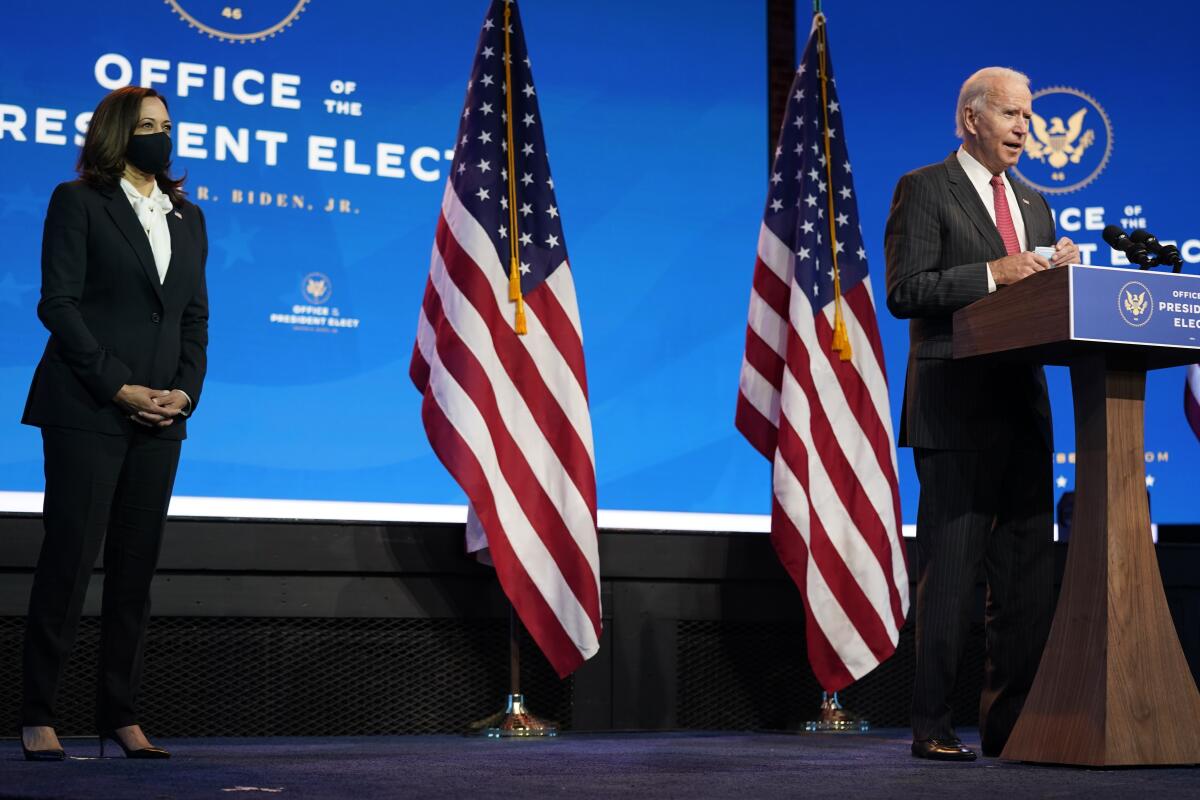

WASHINGTON — When he takes the presidential oath of office in January at the age of 78, Joe Biden will be the oldest person to hold the office. Fighting off the debilitating “lame duck” label is already on his advisors’ to-do list.

As they work to fill White House staff and Cabinet posts and strategize about the new administration’s agenda, top advisors are also trying to figure out how to lay down a marker that Biden, who has portrayed himself as a transitional, stabilizing figure — a bridge to the next generation of Democratic leaders — has not ruled out running for a second term as he approaches 82, according to a source familiar with the transition team’s conversations.

The prospect of Biden serving just a single term will remain a matter of speculation no matter what he says. But the Biden circle’s determination to tamp down the chatter reflects an awareness that such talk could hinder his effectiveness in an already challenging situation, one in which he faces dual economic and public health crises without party majorities in Congress to pass an ambitious response.

Perhaps most of all, unchecked speculation that Biden won’t run again would only encourage divisive jockeying to succeed him among Democratic presidential hopefuls waiting in the wings — from his own vice president, Kamala Harris, to prospective Cabinet secretaries, members of Congress and state leaders.

“It’s a much bigger problem for him within the Democratic Party,” said Alex Conant, a Republican operative and veteran of Florida Sen. Marco Rubio’s 2016 presidential campaign. “To the extent there’s Democrats on the day he’s sworn in angling to be the nominee four years later, that creates a difficult situation for him. Republicans are running for president in 2024 regardless.”

Biden’s confidants — incoming White House Chief of Staff Ron Klain and senior counselor Steve Ricchetti, along with Anita Dunn, who will be an outside advisor — share that view and are determining how best to preemptively defuse a potentially destabilizing situation within the Biden administration and the Democratic Party. Any perceived daylight between the new president and Harris, or between them and essential party allies such as Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, could be magnified by the media into the first skirmishes of a 2024 presidential primary battle.

A Biden transition spokesman pointed to the president-elect’s past comments during the Democratic presidential nomination race, when he said on multiple occasions that he “absolutely” was not ruling out seeking a second term.

Of course, the fact that Biden’s early window to drive his policy agenda is likely a small one is only partly a function of his age. The bigger challenges are the crises he inherits, his party’s narrow margins in both the Democratic-led House and a Senate where Republicans are likely to maintain a majority, and the likelihood that Trump will try to sabotage him constantly from the sidelines, breaking yet another norm — that former presidents fade into retirement and remain mostly mute about their successors’ actions.

Yet the perception of Biden as a lame duck would only add to his trials, encouraging factions when party unity is essential.

“He’s inheriting the worst crisis since FDR and the Great Depression, but he has a much weaker hand than Roosevelt with the Senate in the hands of the other party, the Democratic House majority reduced and Trump refusing to leave the stage,” said David Gergen, who has served as a counselor to presidents of both parties. “It’s going to be very difficult to govern and get big things done. It’s really important that in first 100 days or more that President-elect Biden undersells and overdelivers.”

In the weeks leading up to election day, Biden’s top aides conferred with Democrats on Capitol Hill about an ambitious agenda, including discussions of doing away with the Senate filibuster and a package to combat climate change. They hadn’t planned, however, for Republicans to keep control of the Senate, which will be the case unless Democrats defy the odds and sweep both runoff elections in Georgia on Jan. 5.

“They’re reeling because they thought we were going to get the Senate back,” said one senior Democratic legislative aide involved with the discussions, who requested anonymity to discuss the talks. “Everything is being redefined, from what you do to what you do first.”

The first 100 days of a presidency, historically a new executive’s best opportunity to capitalize on post-election momentum and good feelings, are likely to be especially critical for Biden under the circumstances.

Ronald Reagan, who at 69 in 1981 was the oldest president to take office to that point, allayed much of the anxiety about his age and stamina by empowering his Cabinet and his first chief of staff, James A. Baker III. Reagan’s example offers something of a template for Biden, according to John A. Farrell, a presidential historian.

“If Joe Biden goes upstairs at 6 p.m. and has dinner with his wife on a TV tray, and has a brilliant chief of staff who calls him when he’s needed and knows his limitations, there’s no inherent reason why Biden can’t have a good first term and run again. And I’m sure that he will cloak the notion of a second term because there’s no reason to give up that kind of power.”

When Reagan was shot just two months after taking office, “People didn’t know if he was going to seek a second term,” Farrell said. “And he was easily reelected.”

Mack McLarty, who served as President Clinton’s first chief of staff, said that if Biden can begin his presidency by fostering bipartisan collaboration on economic relief and oversee a successful distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, he could build a foundation for other legislative compromises down the road.

No one in Washington expects Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) to go out of his way to help Biden. Republicans are already eyeing the 2022 midterm elections as a chance to win majorities in both the Senate and House; typically the party not occupying the White House picks up seats at a president’s midterm.

Still, said Mark Mellman, a Democratic pollster, “If Republicans are seen as merely obstructors, it will hurt them politically.”

“Bipartisan cooperation doesn’t come because Democrats and Republicans have martinis and whiskey in the evening. It comes because they are competing for the same people,” said Timothy A. Naftali, a presidential historian at New York University.

“Both parties are competing now for wage earners, for Latino voters, for suburban voters. If that leads to more cooperation, Biden could wind up being a fairly popular president,” he continued. “People tend to care far more about what presidents do than how they look or how old they may be.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.