The 2020 presidential race already in full swing in Wisconsin

BLACK RIVER FALLS, Wis. — It’s more than a year before the presidential election, but across the state of Wisconsin it could be fall 2020.

Dozens of Democratic volunteers were combing neighborhoods to knock on doors in La Crosse and Whitewater on a recent cloudy fall weekend, while volunteers worked phone banks in Milwaukee. Republican county chairs were being trained in grass-roots campaigning in Green Bay and Hayward. And in Jackson County — a rural area that Donald Trump won in 2016 after decades of Democratic dominance — GOP leaders were already working to ready the troops.

“Democrats have been doing everything they can to discredit President Trump,” Doug Rogalla, GOP chairman in neighboring Monroe County, said at a party dinner. “We have to do everything we can to reelect him.”

Most voters across the country are not yet giving much thought to the 2020 presidential election. Those who are paying attention are mostly focused on the big field of Democrats running for their party’s nomination. But in Wisconsin, a state that strategists on both sides think could decide the 2020 race, the parties are arming to the teeth earlier than ever.

“The general election has already started here,” said Ben Wikler, chairman of the Wisconsin Democratic Party, who said a 17-person field staff was in place and canvassers have already knocked on 200,000 doors.

Republicans are holding campaign training sessions for local activists several times a week. The Trump campaign last summer named its Wisconsin state director, months earlier than is typical. Andrew Hitt, chairman of the Wisconsin GOP, said he hears the same refrain as he travels the state.

“It’s crazy, but almost everywhere I went I heard the same thing: We are working now like it’s the summer of 2020, not the summer of 2019.”

The hyper-mobilization here is a reminder of a central fact about the battle over Trump’s reelection: While it will be an expensive and emotional contest with monumental stakes for the country, it may end up being fought in a relatively small number of states.

Most states are so heavily skewed toward one party or the other that their presidential preference can be easily predicted and their electoral college votes taken for granted. Republicans don’t expect to contest California or New York, for example; Democrats have little chance across most of the South and the Great Plains.

Political analysts in both parties predict fewer than a dozen swing states will be seriously contested. Among the most crucial are Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, which Trump won by minuscule margins in 2016.

Of the three, Wisconsin could be the hardest for Democrats to recapture. Its electorate has the highest percentage of white, blue-collar voters— who were a key source of support for Trump — and the lowest percentage of nonwhite voters, Democrats’ strong suit.

One measure of how seriously Democrats take the battle for Wisconsin: They decided to place their 2020 nominating convention in Milwaukee and are using the event to sink deep organizing roots in a state that Hillary Clinton never visited in 2016.

Barack Obama easily carried Wisconsin twice. But his solid margins were exceptions. Most Democrats’ victories in presidential and statewide races have been exceedingly narrow. Al Gore won the state by 0.2 percentage points in 2000; John Kerry won in 2004 by just 0.4 points. In 2018, Tony Evers unseated two-term GOP Gov. Scott Walker by 1.1 points.

Trump’s victory was also by the skin of his teeth: He beat Clinton by 0.7 percentage points, thanks in part to a drop in turnout among Democrats from previous elections and strong showings by two third-party candidates.

The 2020 election is shaping up as another close one. A poll of Wisconsin voters by Marquette University Law School released Wednesday that included hypothetical matchups between Trump and top Democratic contenders found former Vice President Joe Biden leading Trump 50% to 44%. It also gave a polling edge to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, but by narrower margins. Those findings are not significantly different from what the poll found in August.

Wisconsin crystallizes challenges that both parties face nationally, on a battleground sharply split along the rural-urban divide. In 2016, both nationally and in Wisconsin, Trump won thanks to strong turnout in rural areas and smaller cities, overcoming Democrats’ steep advantage in larger cities, where turnout dropped compared with the Obama years.

Now Republicans are facing a Democratic base energized by anti-Trump sentiment and suburbs riddled with moderate Republicans who are turning into swing voters.

To improve over their performance in the 2018 midterm election, Republicans’ No. 1 imperative is motivating the Trump voters who did not show up at the polls. Their vast and sophisticated database has identified more than 188,000 of them.

“We want to get to those 188,000 and get them involved,” said Chris Carr, political director of the Trump reelection campaign. “We’re going to get hard-core Trump supporters — a lot of them are new — to become activists for the president. These are ardent supporters of the president. I promise you these voters are going to show up.”

The Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee are working with the state party to train local party leaders and activists in voter registration, canvassing and other organizing basics. Republicans have already hired 14 field staff around the state and hope to double the 61 GOP staffers that were there in 2016, a Trump campaign official said.

Jackson County, one of 23 Wisconsin counties that Trump flipped from blue to red in 2016, is an important battleground in western Wisconsin. It twice voted for Obama and then for Trump. The 27-point swing was one of the biggest in the state. It is a rural county whose largest city is Black River Falls, population about 3,500.

Bill Laurent, who chairs the county Republican Party, said Trump helped bring out a wave of new Republican voters. He portrays the Democratic Party’s drift to the left as a threat to voters’ freedom.

“We have a major political party, we have major presidential candidates, we have the media touting socialism,” Laurent said of the Democrats agenda at the recent county GOP dinner.

Democrats, meanwhile, are trying to build on their success in the 2018 midterms and avoid the pitfalls of the 2016 presidential election. Wikler said the party fell short against Trump not just because Clinton never campaigned in the state — for which she was widely criticized after the election — but also because the party’s organizing structure was largely dormant until after Clinton clinched the nomination in mid-2016.

After her defeat, then-party chair Martha Laning revived an Obama era organizing style of building a community-based team that would remain active year round, building relationships with the community on issues, not just when an election is before them.

That’s what Anita Loch has been trying to do in Whitewater, a city of about 14,000 between Madison and Milwaukee, where Democrats dominate in the city but Republicans have more strength in the outskirts.

Democrats in the area mobilized for the 2018 midterms and already are reactivating for the 2020 election. Loch’s group, Whitewater Democrats, this summer started hosting presidential debate-watching parties at a local bar to recruit members. They set up an information table at the town’s weekly farmers market. And not long after Labor Day, they started canvassing.

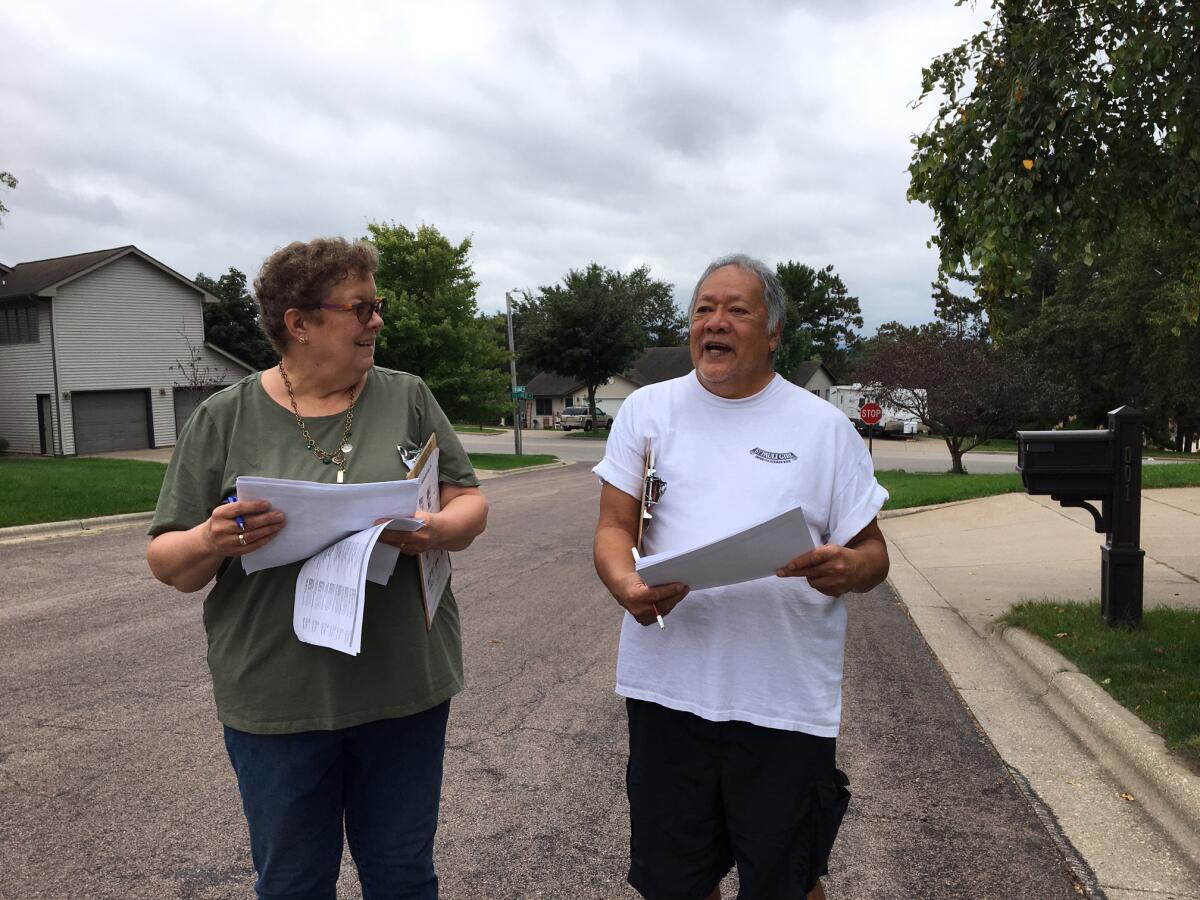

The same thing was going on in La Crosse, on the western edge of the state, as a party organizer greeted volunteers with coffee, rain ponchos and clipboards at the back of a coffee shop. Carol Klitzke, a college teacher who said she had knocked on 100 doors the weekend before, came back for more. She canvassed in the neighboring town of Onalaska with Marlo Santillan, a Philippine immigrant who said he had not been politically active since the 1970s, when he participated in protests in his home country that led to the downfall of Ferdinand Marcos, then the country’s president.

In a couple hours of door knocking, Klitzke identified two voters who had supported Trump in 2016 but seemed persuadable, including Jaclyn Dunnum.

“Trump does a great job, but should not be let out of his office,” Dunnum told Klitzke, referring to the president’s use of Twitter and other verbal attacks that she found counterproductive.

Other voters showed no sign of budging from Trump, including one woman who said opposition to abortion was her main concern.

A big question is whether Democrats in Wisconsin and across the Midwest will be able to make inroads — to at least reduce their losing margin — in the rural areas like Jackson County, possibly by winning over farmers who are getting squeezed by Trump’s farm policies.

“So far there is the tribal loyalty to Trump,” said Charlie Sykes, a conservative who for years had a popular talk radio show in Wisconsin. “We don’t know how long that lasts. He cannot afford to lose a percentage point.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.