Trump, no fan of big cities and their Democratic leaders, unleashes his derision on L.A.

WASHINGTON — One of the most arresting images of Donald Trump’s inaugural address in 2017 was a grim portrait of urban America, riddled by poverty, gangs, drugs and other blight.

“Mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities, rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation,” he said. “This American carnage stops right here and stops right now.”

For the record:

3:02 p.m. Sept. 30, 2019A previous version of this story misidentified Democratic National Committee spokesman Daniel Wessel as David Wessel.

Well over halfway through his presidency, Trump continues to portray urban America in terms of “carnage.” Baltimore, Chicago and Atlanta have each taken turns being portrayed as bastions of crime and dysfunction. His latest is Los Angeles, where he is visiting for campaign fundraisers, just a week after his administration dispatched a busload of officials to scrutinize homelessness in the city.

“We can’t let Los Angeles, San Francisco and numerous other cities destroy themselves by allowing what’s happening,” Trump said to reporters Tuesday, referring to the number of homeless people in those cities and suggesting they were disturbing more affluent residents.

“We have people living in our… best highways, our best streets, our best entrances to buildings and pay tremendous taxes, where people in those buildings pay tremendous taxes, where they went to those locations because of the prestige,” he told reporters on Air Force One as he flew to California.

“In many cases they came from other countries, and they moved to Los Angeles or they moved to San Francisco because of the prestige of the city, and all of a sudden they have tents. Hundreds and hundreds of tents and people living at the entrance to their office building. And they want to leave.”

Trump’s rhetoric sharply contrasts with the reality of most cities, where, despite the visibility of the homeless, crime rates for the last decade have hit historic lows and an influx of new residents have revitalized many neighborhoods. His repeated denigration of cities has offended many urban voters.

None of that, however, carries much direct political risk for the president in his 2020 reelection campaign: He doesn’t need urban voters. He lost the urban vote by almost 2-to-1 in 2016 and still won the election. Anti-urban hostility may help mobilize the rural voters who were the backbone of his 2016 presidential election and whom his campaign needs to turn out at high levels if he is to secure his reelection.

“Trump feeds off the raw emotions of his followers,” said Charles Bullock, a political scientist at the University of Georgia who has studied the presidency. “He paints a picture of an urban landscape that his people would not want to live in.”

The urban-rural split will be a particularly important fault line in 2020 in three of the states that are crucial to Trump’s political prospects: Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — swing states where surging turnout in rural areas helped him overcome big losses in Democratic-dominated cities in 2016.

One risk of Trump’s city-bashing could be to alienate voters in suburban counties, which are shaping up to be a key battleground for the 2020 election.

“The population that is a hazard for him in this area are people who are highly educated and conservative leaning, who think of themselves as Republican but are not so enamored of his leadership style,” said Katherine Cramer, author of a book about Wisconsin’s former GOP governor, “The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker.”

“Their livelihood depends on urban economies.”

For Trump, attacks on big cities are also a way of going after their Democratic leadership. California, whose elected officials have frequently sued his administration and opposed his policies, has been a special target. The president has fired off more than 200 messages on Twitter — his favored platform — about California since taking office.

Nationally, a July 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that 55% of rural residents approved of Trump’s job performance — far more than the 23% of city dwellers who approved, but down from the 61% of rural voters who voted for him in 2016, according to exit polls.

John Anzalone, a Democratic pollster who is working with former Vice President Joe Biden’s presidential campaign, said that Democrats have an opportunity to make gains among rural voters in 2020, even if they have little hope of winning a majority. Winning back disillusioned rural voters could help Democrats reduce the GOP margin of victory.

“There will be a huge effort by a lot of groups to make sure Democrats communicate in rural and exurban areas,” he said.

Trump’s effort to remind his supporters of what they dislike about urban areas is one way to combat that Democratic effort.

Tensions between urban and rural America — divided by social, cultural and racial factors — date back to the nation’s founding and the split between rural-dominated slave states and more-urban northern states.

But GOP domination of rural areas has grown in recent years. Trump’s rise has accelerated the division between the two, adding an explicit racial dimension, as his attacks on cities are often personified by attacks on people of color who represent them, such as Rep. Elijah Cummings of Baltimore and John Lewis of Atlanta.

In 2016, Trump won just four of the 50 most populous counties in the U.S. in 2016. Trump in 2016 drew 23.5% of the vote in Los Angeles County and a mere 9.9% in his home county of New York.

Overall, Hillary Clinton won 62.2% of the vote in the 50 most populous counties to Trump’s 32.8%. That margin was four points wider than the gap in 2012.

Down-ballot races since 2016 have indicated that the urban-rural split has continued to grow.

In the 2018 midterms, a banner year for Democrats nationally, big Republican margins in rural counties assured the election of Republican governors in Florida and Iowa in spite of increased Democratic turnout in urban areas.

And in a recent special House election in North Carolina, the Democratic candidate performed better in suburban Charlotte than he had in 2018. Every other county in the mostly rural district swung more Republican.

In the U.S. today, just one of the 10 most populous cities has a Republican mayor — San Diego’s Kevin Faulconer, who has been at odds with the president on his proposed border wall.

Trump has been especially harsh in his criticism of “sanctuary cities” — including Los Angeles — because of their willingness to offer political support or protection for people who are in the U.S. illegally.

“Democrats support deadly sanctuary cities,” he said in New Hampshire in August. “Republicans believe our cities should be sanctuaries for law-abiding Americans, not for criminal aliens.”

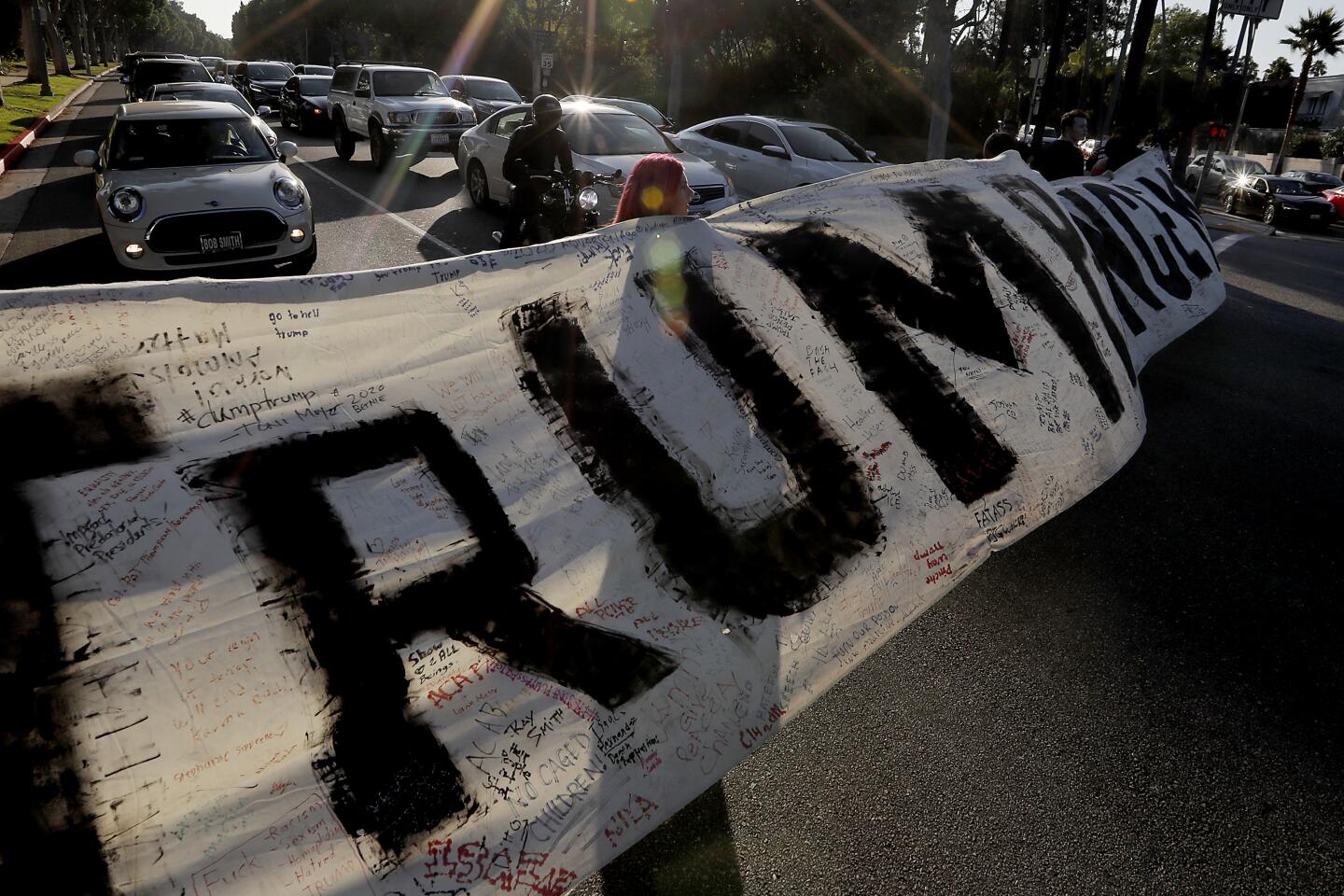

It’s no wonder that Trump almost never holds his signature campaign rallies in the middle of a big city. He tried one rally in Chicago early in the 2016 campaign. Thousands of protesters showed up a day in advance, some got into the arena, and at the last minute Trump canceled the rally due to “safety concerns.”

The ensuing brawl between Trump fans and anti-Trump protesters provided fodder for Trump, who blamed “thugs” for the violence and suggested the backlash to the incident might help him.

“The organized group of people, many of them thugs, who shut down our First Amendment rights in Chicago, have totally energized America!” Trump tweeted, just days before the crucial 2016 Florida primary.

Still, Trump does try to claim credit for help to cities with policies such as his support for a bipartisan bill to overhaul the criminal justice system and the creation of “opportunity zones,” tax breaks in Trump’s 2017 tax bill designed to encourage investment in economically distressed neighborhoods.

“I think what I’ve done for the inner cities is more than any president has done for a long time,” Trump said Monday.

His decision to embrace the criminal justice bill did give him a legislative accomplishment, but he was a bit player in the work it took to craft and advance the bill through Congress.

Critics of the tax breaks say the opportunity zones were supposed to target high-poverty neighborhoods, but that much of the benefit has gone to trendy neighborhoods and real estate investors.

“Trump has miserably failed to revitalize inner cities,” said Daniel Wessel, a spokesman for the Democratic National Committee. “He’s done nothing to fix crumbling roads and bridges, he’s done nothing to address the racial wealth gap that punishes black communities, and the corporate profits from his tax law that he said would be invested in cities have largely gone toward buybacks for wealthy shareholders.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.