Editorial: Give voters a chance to fix California’s recall system

California is on the verge of losing a golden opportunity to finally fix its problematic recall rules.

After the state’s first gubernatorial recall election — the 2003 ouster of Gov. Gray Davis — legal scholars and lawmakers called for significant changes to the procedure to remove governors and other state officials. Noting there had been 25 lawsuits over the election and a circus-like campaign with 135 candidates seeking to replace Davis, they proposed ways to curb some of the chaos and confusion. Among them: Raise the number of signatures needed to qualify a recall for the ballot; limit when recalls can take place so officials can’t be ousted right after an election or within six months of the end of their term; assign the lieutenant governor to take over if voters kick the governor out of office.

But the energy generated in Capitol hearing rooms and at university symposiums fizzled out, public attention moved on, and California’s wacky recall rules remained in place.

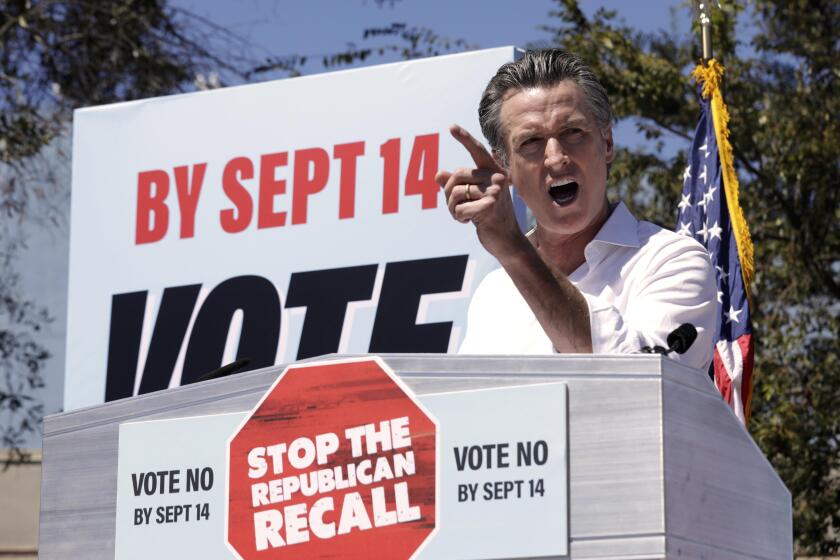

Fast-forward to 2021, when for the second time in state history California voters were asked to recall a governor. Gov. Gavin Newsom won resoundingly with 62% of the vote. But like last time, after the election was over, legal scholars and elected officials called for changing the recall procedure. Again they held legislative hearings and academic symposiums. Again they considered raising the number of signatures needed to qualify a recall for the ballot, limiting when recalls can occur and assigning the lieutenant governor to take over if a governor is ousted.

And again, the reform proposals are fizzling.

Unless state lawmakers act by the end of this month to put a constitutional amendment on the November ballot — which now appears unlikely — California will remain stuck with the same ridiculous recall rules.

California must fix the gravest flaw in our recall system: that a winner can prevail with a small sliver of the vote.

The worst feature of the state’s system is that it creates the possibility that an elected official can be thrown out of office and replaced by someone voters like even less. That’s because California’s recall procedure involves two questions — first, whether to recall the official, and second, to pick a replacement. While it takes a majority of “yes” votes to recall an official, the person winning the seat need only get more votes than any other candidate on the ballot.

Imagine that 49% of voters had voted to keep Newsom in office. He would have been recalled and replaced by whomever received the most votes — even if that person received, say, 20% of the votes, which is feasible in a field of dozens of candidates.

This system has led to bizarre and undemocratic outcomes in some recalls of state lawmakers. For instance, state Sen. Josh Newman (D-Fullerton) was recalled in 2018 because only 42% of voters chose to keep him in office. But he was replaced by Ling Ling Chang (R-Diamond Bar), who topped a six-person field with support from even fewer voters — just 34%. In raw numbers it worked out like this: 66,197 people voted to keep Newman, and 50,215 voted to elect Chang. But Chang won and Newman lost.

So much for the notion that the person with the most votes wins.

This flaw also undermines the power of the recall as a legitimate tool to help voters hold elected officials accountable. Instead, absent an Arnold Schwarzenegger-like superstar with broad appeal, it’s made the recall a potential path to victory for unpopular politicians. Many Republicans acknowledged as much during the Newsom recall campaign, saying they saw an opportunity to win the state’s top office that wouldn’t exist in a regular race in this blue state.

Lawmakers could take a step toward fixing this problem by passing Senate Constitutional Amendment 6 and placing it on the November ballot. The measure asks voters to limit recall elections of state officers and legislators to a single yes/no question and creates a new procedure for replacing officials who are recalled.

The replacement procedure would be the same as what happens when state officials resign or die: If a governor is recalled, the lieutenant governor would take over. (If the recall happened in the first half of the governor’s four-year term, the lieutenant governor would be in charge until a special election to choose a replacement is held at the same time as elections are normally scheduled.) If another statewide officer is recalled — such as the superintendent of public instruction, lieutenant governor, secretary of state, controller, treasurer or attorney general — the governor would appoint a replacement.

For state lawmakers who are recalled, the measure calls for holding a special election in which the replacement would have to win a majority of votes.

California’s gubernatorial recall process needs some adjustments to promote democratic oversight while eliminating undemocratic takeovers.

This is a smart reform that ensures winners have broad support from the electorate while retaining the recall’s important power in California’s system of direct democracy.

Unfortunately, the proposal is likely going nowhere this year. Newman — the Orange County legislator who was recalled in 2018 won his seat back in 2020 and wrote this measure to change the recall — told a Times editorial board member that he will probably wait to try to put it on the ballot in 2024 instead. He’s concerned this year’s ballot will be too cluttered with other measures, making it hard for an election-reform proposal to compete for attention.

Other proposals to change the recall are also stalling. A measure asking voters to allow the subject of a recall to appear as a candidate on the second question of the recall ballot has not been scheduled for a hearing and appears unlikely to advance. Polling by the Public Policy Institute of California shows just 42% of likely voters would approve this reform, and lawmakers are reluctant to put a proposal on the ballot that is unlikely to pass.

But the same poll also shows that 59% of likely voters want to vote on changes to the recall this year. Californians have now lived through two gubernatorial recalls in less than two decades — that’s half the gubernatorial recalls that have ever taken place in this nation — and want to weigh in on changes.

Because California’s recall system was created by voters back in 1911, any significant alterations to it must also be approved by voters. The Legislature faces a June 30 deadline to place measures on the November ballot. They should give voters the chance to fix the recall’s biggest flaw — the possibility that a winner can prevail with minority support. Otherwise, they’re taking the risk that in the next recall, a loser will win.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.