California Politics: Who wants to fix recall elections?

In a way, it feels like the recall campaign against Gov. Gavin Newsom isn’t over.

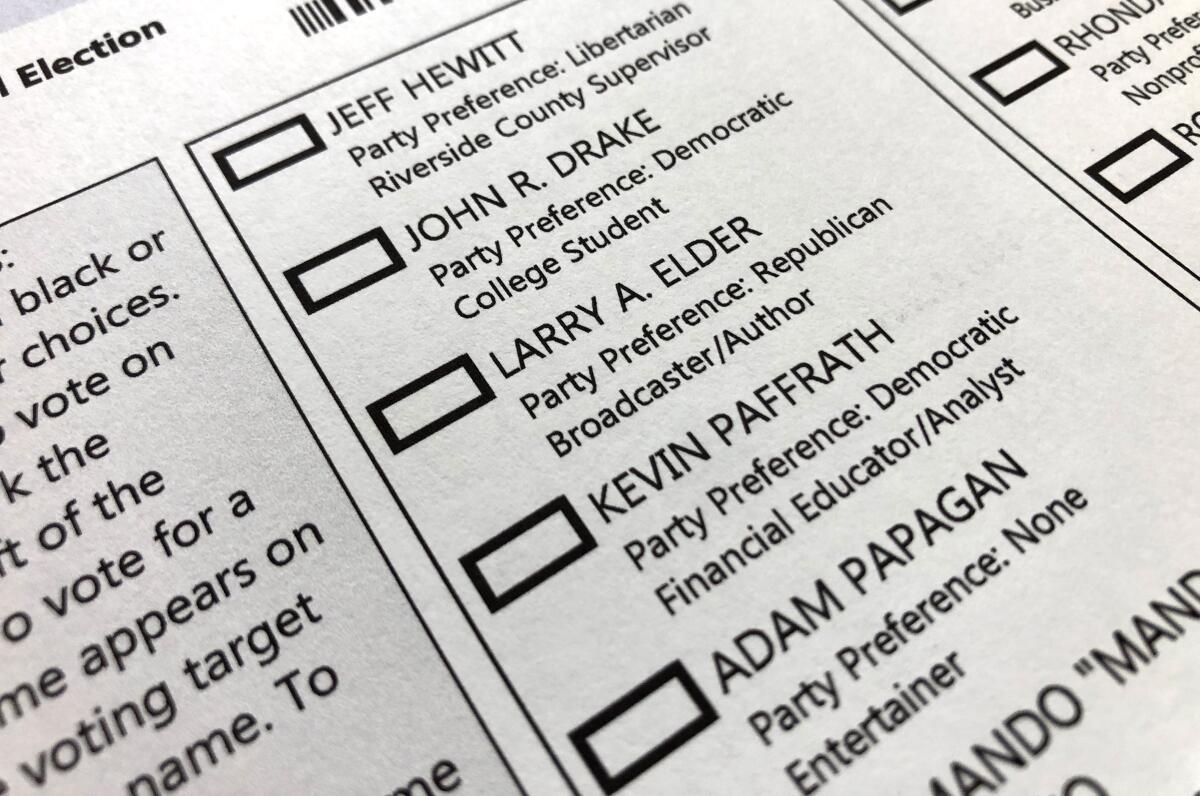

Sure, the election results have been certified and Newsom will serve out the remainder of his term while the replacement candidates settle for a spot in the history books.

But the discussion prompted by the recall — and the demands for reform, sparked by a chorus of complaints about how these special elections work — is only getting started.

Two public hearings Thursday in Sacramento made clear there are a lot of options floating around for revamping a tool of California’s direct democracy that’s only been slightly tweaked since its creation in 1911.

The events also served as a reminder that consensus in these hyper-partisan times will be tough — if not impossible — with some who already suspect that efforts to revise the rules are a political Trojan horse, designed to secretly tip the scales in a recall election.

On the other hand, election officials view the recent gubernatorial recall as a white-knuckle ride that could have ended in disaster.

1911 collides with 2021

“It really is an amazing thing that we conducted this election in September successfully in California,” Cathy Darling-Allen, the registrar of voters in Shasta County, told members of the Little Hoover Commission, the state’s government oversight and reform agency.

There’s one big difference between the recall and the initiative and referendum, the other two pillars of the state’s system of direct democracy championed by then-Gov. Hiram Johnson more than a century ago: The recall generally triggers a separate and unscheduled election. That requires counties not only to launch special preparations but to manage the ways the recall rules crash into multiple laws governing California elections that have been recently enacted.

The Newsom recall effort set in motion a 75-day timeline, but recall elections can be called in as few as 60 days after the voter-signed petitions are certified. But the state’s new law requiring ballots to be mailed to all voters lays out a requirement to begin those deliveries 29 days before an election. That leaves only a small window of time for county registrars of voters to focus on finding voting locations for those who choose to show up in person, train workers for those sites and complete tasks such as assembling voter guides and prepping to count ballots.

“The current recall statutes both in the election code and the California Constitution were developed and enacted when the model for conducting elections in California was primarily in person on election day,” Allen said. “That is no longer the case.”

Small or sweeping recall changes?

“There’s a lot of opportunity to tweak things to maybe make it a little more appropriate,” said Assemblyman Marc Berman (D-Palo Alto) during Thursday’s second recall hearing, jointly held by the Legislature’s two elections committees.

But some of the ideas discussed by lawmakers and reform advocates would go far beyond a tweak.

Members of both panels discussed raising the threshold of voter signatures needed to trigger a recall election against a statewide official, currently set at a number equal to 12% of the votes cast in the most recent gubernatorial election. Some suggested a percentage of the registered electorate while others suggested changes to ensure signatures would be collected in more counties and not just regions politically opposed to the incumbent.

They also heard testimony regarding the number of days given to gather those signatures (California offers more time than any other state) and the potential of requiring some sort of crimes or malfeasance by an elected official before allowing a special election to remove them from office.

Also discussed: whether a vacancy caused by a successful recall should be filled by an appointment, with the lieutenant governor taking office if the governor is removed. And the panels considered arguments in support of splitting the recall’s two questions — should the governor be removed and, if so, who should replace the incumbent — into separate elections.

Big changes would require amending the California Constitution, something that can be done only by voters and could happen as soon as June if the plan is crafted by the Legislature, or November if drafted by outside groups. Small changes, though, could be made by lawmakers. But in the case of legislative action, political optics could loom large.

“If there’s one thing that tends to unite our voters — not just Democrats, not just Republicans, but all voters — it’s the whiff of anything that would look like taking power away from them,” said Jessica Levinson, a Loyola Law School professor.

That was largely the complaint lodged by the organizers of the effort to recall Newsom, who were in the audience of the legislative hearing at the state Capitol.

“They want your hands out of the process,” Orrin Heatlie, the proponent of the anti-Newsom campaign, told lawmakers when it comes to the will of the voters. “This is a process of the people by the people and for the people.”

One fix? Lots of fixes?

Over the course of several elections in the mid-20th century, California voters were persuaded to make constitutional changes through omnibus proposals placed on the statewide ballot — nips and tucks to modernize the state’s governing blueprint.

Could that happen again when it comes to the recall?

Witnesses at the two hearings urged caution about any effort to craft a single, multilayered proposal to revise California’s recall rules, warning that varying degrees of support for individual provisions could doom the entire effort.

Several recall-related ballot measures would “give more opportunities for voters to deliberate and decide,” UC Riverside Professor Karthick Ramakrishnan told members of the Little Hoover Commission. “So they may decide that they like, say, two or three out of five provisions.”

During the legislative hearing, there was little if any bipartisan agreement on changing the process, with Republicans arguing that because so few efforts over the past 110 years have made it to the ballot, there hasn’t been a tidal wave of unwarranted recalls.

“I don’t think there’s anything too egregiously broken in California’s system right now,” said state Sen. Jim Nielsen (R-Red Bluff).

Democrats, who have enough legislative seats to put anything they want on the 2022 statewide ballot without GOP support, sounded a different note — no doubt mindful that the results of the Sept. 14 recall election (61.9% of voters backing Newsom) were the same as the governor’s race in 2018.

“The recall was not intended to be and must not become a backdoor for the losing side of an election to relitigate those results,” said state Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda).

One interesting suggestion was made by Ramakrishnan, who directs UC Riverside’s Center for Social Innovation: Place an expiration date on any constitutional changes made to the recall process, a time at which either the rules revert back to their current configuration or voters get a chance to come up with other ideas.

“Just like Prop. 30 [in 2012] created a temporary tax increase without foisting it upon California permanently, we may want to think about reforms where we don’t yet know what the results of these experiments are going to be, and not being stuck with it,” he told the Little Hoover Commission.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Newsom heads to Scotland

California’s approach to climate change will again hit the international stage next week, when Newsom travels to the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland.

The governor is leading a delegation of state lawmakers and environmental leaders, according to an advisory from his office, to “make the case that the state needs national and international partners to join us in committing to safeguard our future.”

One topic expected to be discussed is California’s plans for phasing out the sale of new gasoline-powered automobiles by 2035. Newsom’s aides also plan to discuss the state’s progress in relying on renewable energy sources.

My colleague Taryn Luna will be traveling with the governor; look for her coverage in The Times early next week.

Visualizing new political maps

It’s been a big week in the effort to redraw California’s congressional and legislative maps, as the state’s Citizens Redistricting Commission unveiled a detailed set of what it calls “visualizations” for 52 House districts, 40 state Senate districts and 80 Assembly districts.

Note the use of the term “visualizations” — the commissioners insist the sketches are simply designed to help facilitate their discussion of how information gathered from months of public testimony might look once it’s laid out on a map of the state’s 58 counties. The first official draft maps are scheduled to be released on Nov. 10.

While the commission isn’t using political party registration as it draws the lines, others are already reviewing the potential impacts. An analysis by the nonpartisan Target Book of the visualizations for congressional maps could result in as few as nine districts with a clear advantage for Republicans, who hold 11 of the existing seats. Even so, a number of the sketches resulted in razor-thin advantages for one party or the other, the kind of split-decision that could make the 2022 midterms particularly hard-fought.

California politics lightning round

— Weeks after a massive oil spill marred the Orange County coast, state lawmakers met Thursday to demand that those responsible “be held accountable,” with one legislator calling for an end to offshore drilling in California.

— Many California government agencies face low vaccination rates, and most state-run workplaces have failed to test unvaccinated employees.

— California has given away at least $20 billion to criminals in the form of fraudulent unemployment benefits, state officials said Monday, confirming a number smaller than originally feared but one that still accounts for more than 11% of all benefits paid since the start of the pandemic.

— The application window for a new $1,000-a-month cash assistance program in Los Angeles run by City Hall kicks off Friday, making L.A. the biggest city in the nation to launch such an initiative.

Stay in touch

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get California Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.