6,297 Chinese restaurants and hungry for more

David Chan, an L.A. attorney, will try any Chinese restaurant once and has the spreadsheet to prove it. He has become a go-to expert for critics.

The television cameras roll as Los Angeles attorney David Chan places the first forkful of cashew chicken in his mouth.

The crowd at Leong's Asian Diner in Springfield, Mo., falls silent as he chews and squints in the glare of the lights.

Springfield Cashew Chicken — a deep-fried, gravy-drenched version of the popular buffet item — is a local specialty and David Leong, the dish's 92-year-old inventor, was watching expectantly from across the table.

Chan kept chewing. The silence grew uncomfortable.

"How does it taste?" a reporter asked at last.

Chan didn't answer. The chicken was overcooked.

Finally, he spoke: "It's good," Chan mumbled diplomatically, and quickly grabbed seconds.

Archive: David Chan chats with readers

Chan, 64, has eaten at 6,297 Chinese restaurants (at press time) and he has documented the experiences on an Excel spreadsheet, a data-centric diary of a gastronomic journey that spans the United States and beyond.

A lawyer and accountant by trade, the slim, bespectacled man can debate Toronto's dim sum and rate Chinese buffets in Nashville. Name any neighborhood in Los Angeles and Chan — with a few thoughtful blinks — will produce the name of a Chinese restaurant within a few miles.

His expertise has brought him renown. Restaurant critics regularly ask him on Twitter for advice on where to eat. Food websites have sought him out to write about Chinese cuisine and its history. In Springfield, his lunch made the local news broadcasts — at 6, 9, and 10 p.m.

Scrolling to the top of his spreadsheet takes you to 1955 and a different era in Los Angeles. The only Chinese food was in Chinatown, and food was his sole connection to his culture.

#2, 1955, soy sauce over white rice at Lime House, 708 New High St. A green-painted concrete square with crisscrossing telephone wires overhead. Keep reading »

As a child, Chan hated Chinese food. The few times his parents would drag him to Chinatown restaurants like Lime House for banquets, he'd sulk over a bowl of plain rice. Home-cooked dinners were American standbys like meatloaf and spaghetti.

If Chan didn't feel Chinese, it was partly by design.

"I think my parents wanted to protect me," Chan said. "I was pretty much raised as an American."

If Chan didn't feel Chinese, it was partly by design.

Immigration quotas then allowed just 105 Chinese into the country each year, and only 8,067 Chinese lived in Los Angeles in 1950 — less than half a percent of L.A.'s population at the time, according to census records.

"Unless you lived in San Francisco, you were an oddity," said Chan, a third-generation Asian American.

His father graduated from UCLA at the top of his accounting class, but the job offers from top firms never came. They lived in a neighborhood that real estate agents had counseled them was "accepting of Chinese," and his parents never sent him to Chinese school because they were afraid his English would suffer.

But Chinese food was always there, marking birthdays, weddings and graduations. While studying accounting and tax law at UCLA, Chan frequented a restaurant in a high-rise called Ah Fong's Westwood. It was the only Chinese restaurant in the area that he could recall.

#28, 1972, fried rice at Ah Fong's Westwood at 1100 Glendon Avenue. A top floor high-rise restaurant space with ornate wooden chairs and chandeliers overhead.

At UCLA, Chan felt he was no longer an oddity. Laws passed in 1965 loosened immigration restrictions and about 9% of the students identified themselves as Oriental American, according to a 1971 university survey. There, Chan took a class called Orientals in America, which was the first Asian American studies course offered at UCLA. He began to read everything he could find on the subject.

David Chan's Top Ten Chinese restaurants

"It helped me recognize the fact that there weren't very many of us around. And we were discriminated against, and because of that the roads to achievement were not the same," Chan said.

After graduation, Chan took a job at a large accounting firm and befriended a group of co-workers from Hong Kong. He couldn't speak Cantonese with them, and he didn't know how to use chopsticks. But what he had in common with them was a love of Chinese food.

One day they went to lunch and ordered a dish of fried boneless chicken with crispy skin, lightly touched with a sweet-and-savory lemon glaze. It was like nothing Chan had ever tasted.

#215, 1984, dim sum and lemon chicken at ABC Seafood, 205 Ord St. Los Angeles, CA. A gray concrete corner lot with neon signage and faux-greek entrance columns.

Lemon chicken was the product of a new wave of Chinese immigrants who flocked to the Southland in the 1970s, lured by promises of a Chinese Beverly Hills in Monterey Park. Lush banquet halls serving Hong Kong cuisine suddenly proliferated across the San Gabriel Valley. Chinatown boomed.

Chan and his co-workers launched a lunchtime campaign to try every Chinese restaurant as it opened, amassing a trove of menus and business cards. Chan checked phone books for new restaurants. Adding to his list became a growing obsession.

"I've always been a collector. I collected stamps, and records," Chan said.

As Chinese food spread across the Southland and the nation, Chan tried to keep pace, hitting more than 300 new Chinese restaurants a year at his peak. He kept meticulous records on a spreadsheet, which today numbers 6,297 - and counting. Check out his Top Ten here.

If his friends gave a poor review to a restaurant, Chan would eat there anyway. Perhaps they ordered the wrong dish, or the cook was having a bad day. He had to see for himself.

Chan was eating at new restaurants faster than they could open up. Soon there wasn't a single one in the area he hadn't tried, but still, he was unsatisfied.

In 1985, he hit 86 restaurants in the Los Angeles area and around the country. The next year, 119. Before long he was trying more than 300 restaurants every year.

In Toronto, he hit six dim sum restaurants in six hours. When he traveled for business in Florida, he zigzagged the state to sample 20 Chinese restaurants.

Chan had always wanted to travel to all 50 states, and Chinese food gave him an excuse. In places he would have never imagined, he found Chinese people with their own version of Chinese food.

Chan had always wanted to travel to all 50 states, and Chinese food gave him an excuse.

In New England, he encountered a chow mein sandwich topped with gravy. In St. Paul, Minn., he found a burger with egg foo young for a patty. Throughout the South, he came across a sweet, stir-fry dish called Honey Chicken.

"It doesn't have to be authentic Chinese. If it's Chinese American, it's all the more interesting," Chan said.

Chan rarely discussed his list. His son, Eric Chan, was only vaguely aware of it growing up. "There are a lot of things my dad doesn't talk about," he said.

In their family, a meal often said what words couldn't, Eric Chan said. During the three years he studied law at Stanford, his father visited about 20 times. They'd dine in San Francisco dim sum houses and San Jose noodle shops.

"If you collect enough of something, you can capture its essence," Eric Chan said. "Maybe that's what he's trying to do with food."

Chan rarely eats somewhere twice, but he keeps going back to ABC Seafood, even after the restaurant's ownership changed and, he said, the lemon chicken lost its flavor. Chan says he does it out of respect for history. He's dined at practically every Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles, but few culinary experiences can match that first meal at ABC Seafood.

"For a good portion of when they were open, they were the best Chinese restaurant in the country," Chan said.

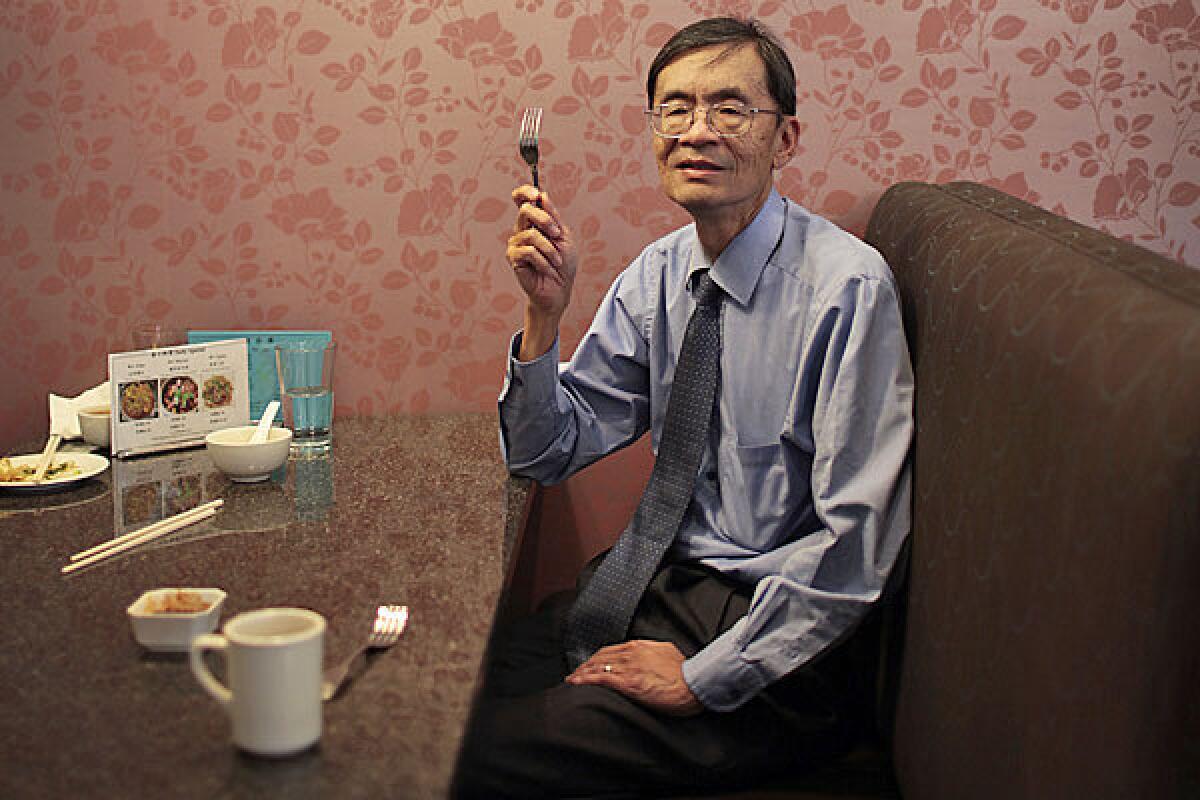

David Chan, left, dines at Shawn Cafe in Arcadia. His expertise has brought him renown. Restaurant critics regularly ask him on Twitter for advice on where to eat. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

#6,235, 2012, Shandong beef roll, stinky tofu, stir-fry rice cakes and mixed vegetables, Shawn Cafe, 1220 South Baldwin Ave in Arcadia. Flower patterned walls. Wall-mounted flatscreens showing Chinese-language news channels.

Chan slides into a booth at Shawn Cafe, one of the few Chinese restaurants in the Los Angeles area he hasn't tried. It's a modern Taiwanese eatery that opened in December. He glances over the menu with a bored look — there's little he hasn't seen before.

"Rumor Has It" by Adele plays over the restaurant's speakers as Chan's hands curl around another trusty fork.

He's tried to use chopsticks over the years, and a friend even bought him a spring-loaded pair as a gag birthday gift.

The fork feels more natural, he said, as he stabbed a section of beef roll and took yet another bite of Chinese food.

Archive: David Chan chats with readers

Follow @frankshyong on Twitter

More great reads:

Given up for adoption, but not for lost

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.