Given up for adoption, but not for lost

Spurred by a deathbed promise to her grandmother, a woman wins a 15-year battle with social workers to be reunited with her younger siblings.

Almost from the start, it was just the two of them.

When Marilyn was 4 and her brother Aubrey was 3, she packed peanut butter and they ran away from their abusive foster home. Racing across California desert roads, they imagined reaching Barbie's house and a world of play and safety. But authorities returned them to the home a few hours later.

Their foster families changed frequently after that, as well as their surroundings. As they packed and unpacked, Marilyn carried a few fleeting memories of her real family. Aubrey had none.

Sometimes when they played in a Georgia subdivision, they pretended to be explorers discovering new lands, fighting goblins, trolls and giants.

They called it the Adventures of Marilyn and Aubrey.

Thousands of miles away in Los Angeles, a young mother named Meredith Kensington loved to create stories for her daughter. Their favorite one was about two special children who were split from their family by an act of cruelty and led a royal life full of adventure, peril and triumph.

The plot changed, yet one theme was steady: The weak were rarely bullied for long.

They called it the Adventures of Marilyn and Aubrey.

But the story never had an ending.

Fairy tales are rare in Los Angeles County's foster care system. As a girl, Meredith Kensington resolved to live one.

Her mother and father struggled with drugs and alcohol. Between both parents, she has 14 half siblings and two full siblings, both years younger: Marilyn and Aubrey. Courts eventually took away her mother and father's parental rights to many of their children.

In their absence, Meredith's grandmother held the family together, even though the children were scattered across various foster homes. She cared for Marilyn and Aubrey herself.

But her grandmother died when Meredith was in the seventh grade. On her deathbed, she asked Meredith to look after Marilyn and Aubrey, and the older girl promised that she would.

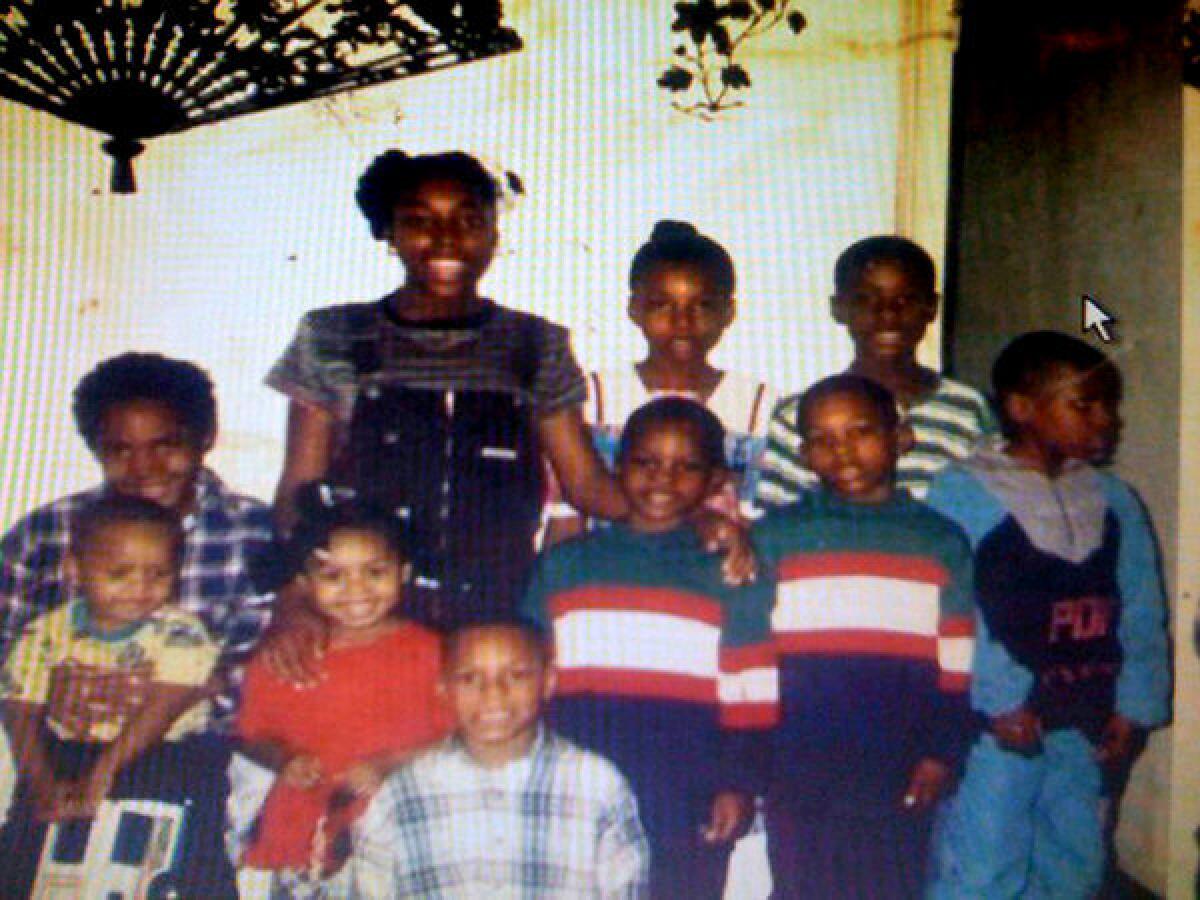

Meredith Kensington, upper left, with her younger sister Marilyn, who is wearing a red dress. Her younger brother Aubrey is wearing a yellow shirt. More photos

Instead, the two children were moved into another foster home, and the family was seemingly split forever by a wall of bureaucratic indifference. In a paperwork mix-up that apparently confused Meredith with her mother, who had the same name at the time, no one would allow them to stay in touch.

Over 15 years of persistent effort, Meredith pleaded with social workers, even stealing little snippets of her siblings' confidential files while workers were looking the other way, and filed court petitions asking to be reunited with her brother and sister.

The Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services has policies meant to keep siblings together in the same home or at least guarantee continued contact, but other priorities often intervene.

An overworked social worker may not want to work after hours to facilitate contact. A foster or adoptive parent often doesn't want the trouble that they worry contact might bring.

Bill Thomas, who leads the agency's post-adoption unit, said he couldn't explain why Meredith encountered so much trouble. But he noted that putting children in touch with siblings after adoption receives no federal or state financial support, and that Los Angeles County is unusual in making any effort at all.

"We don't do too many reunions, but it's one of the things we love to do," he said.

As time went on, the tedious failures of Meredith's pursuit became grist for a reunion fantasy that she couldn't relinquish.

In her daughter Alani's eyes, the bighearted heroine of the story was her mother, now 29, who never abandoned her effort to fulfill her grandmother's dying wish.

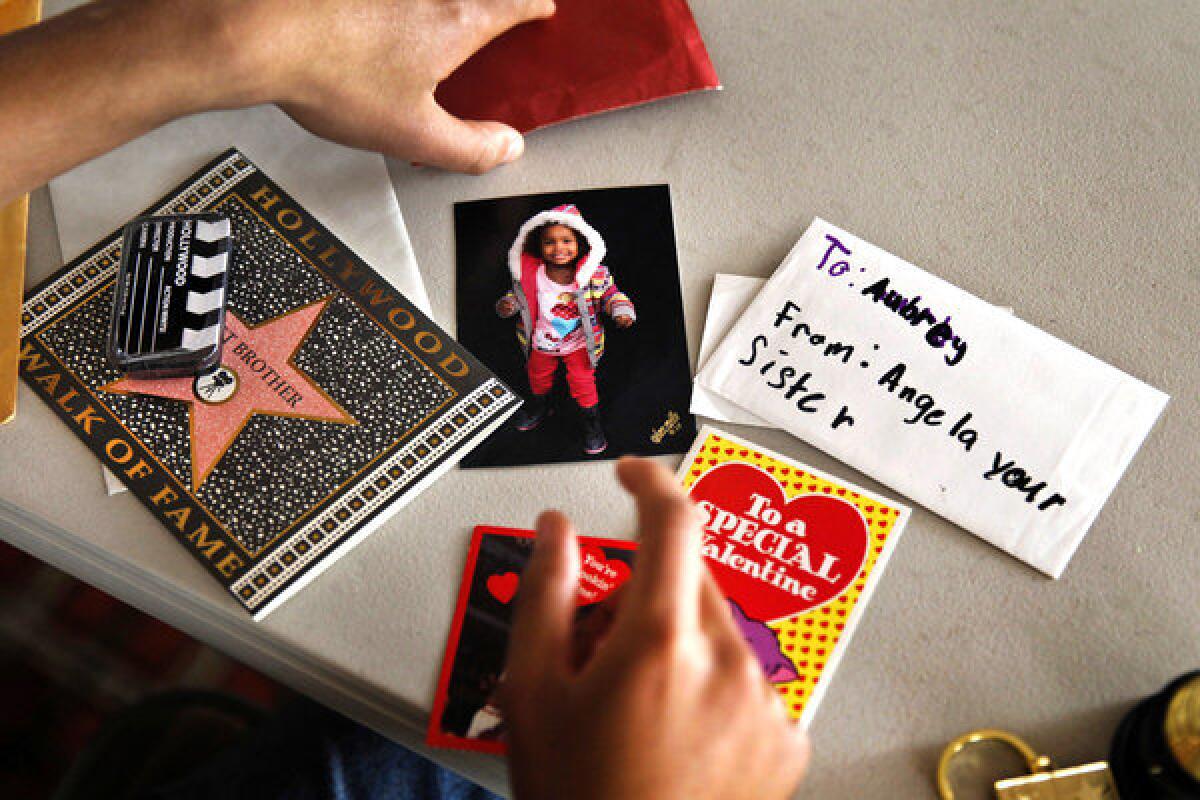

Aubrey Haynes,18, looks over old Valentine's Day cards and family photos given to him by his sister Meredith Kensington. More photos

When The Times published an article in December about her search, county officials located an address within days and asked Marilyn and Aubrey if they wanted to be placed in touch.

An ending to the story was finally possible.

Meredith was notified in January that a letter was being sent to Marilyn and Aubrey asking if they wanted contact.

As she waited for a reply, doubts intruded about her siblings' willingness to reconnect. So much time had passed. The last real contact occurred when the family was planning a 1997 Valentine's Day party. Her 3-year-old sister and 2-year-old brother failed to show up. No one knows why.

Marilyn and Aubrey had a new surname — Haynes — from their adoptive parents in South Carolina and had mostly forgotten about their family in California.

"They were separate. Just separate," said Marilyn, now 19, who struggles with the fallout of those years of feeling adrift.

Unconditional love — there's nothing like it. I want to live up to my new family's picture of me."— Marilyn Haynes

To get ready for proms, talk about love lives and stage graduation photos, it was just the two of them.

"Marilyn was my sun and I was the pesky little brother," Aubrey, 18, said.

By the time the children's services letter came telling them about Meredith, they were intrigued and open — but afraid they couldn't fulfill anyone's ... fairy tale.

"I was just worried that I couldn't live up to the idea of the long-lost brother who has been placed on a pedestal for all these years," Aubrey said.

A somewhat shy young man, Aubrey studies film in South Carolina and is drawn to more somber stories, often ending in tragedy.

"I really love Clint Eastwood's late career. Can you imagine the research that went into 'Changeling?' " — another story about a lost boy, with an unhappy ending.

Marilyn and Aubrey agreed to allow children's services to give Meredith their phone number, and they braced for the consequences.

Their adoptive mother called Aubrey and her voice betrayed her fear that they were going to abandon her for their birth family.

"Hey Aubrey," the phone crackled, "this is Levern. I mean, your mom."

"Mom, you're still my mom," Aubrey replied softly.

Days later, Aubrey was in a Chick-fil-A when his phone started rattling with calls from California. Too nervous to pick up, he let them pass to voice mail.

He went home and paced the floor and listened. "The messages," he said, "were so heartfelt and dramatic."

Then the phone buzzed again. It was his older half brother Greg. He said Aubrey was named after their grandfather, that Aubrey was the brother he always longed to have and that Aubrey's voice sounded exactly the way he always imagined. He told Aubrey about the incredible lengths Meredith had gone to find them.

What's been going on with you?

"Uh, I can't really match that," Aubrey remembers saying. "I went to high school?"

Meredith's conversations with Marilyn contained difficult news. Her relationship with her adoptive parents was strained and she no longer lived at home. She was relying on the kindness of friends and their waning patience for her overnight visits. A bright girl who dreamed of a nursing career, she felt cornered.

Meredith, more determined than ever, decided to supplement her income as an aesthetician with a second job doing security for the Academy Awards to buy plane tickets for Marilyn and Aubrey to visit. They planned it for Aubrey's spring break.

Meredith, a single mother, worked six weeks straight, often riding the bus to and from her one-bedroom apartment in Westlake to work 16-hour double shifts and split shifts as a security guard. Meredith's godparents helped care for Alani.

At the end of each pay period, the price of the flights rose faster than her bank account. She considered pawning the television. She sold some of her shoes.

Two days before the planned visit, she had the $1,393.

Meredith Kensington, center, hands out Valentine's Day cards she had saved for more than 15 years for her brother Aubrey Haynes, 18, right, and sister Marilyn, 19, far right. More photos

For Marilyn, it was a one-way ticket. She was moving in with Meredith and her daughter in their small apartment. Landing in Los Angeles, she looked out across the horizon at a place with limitless possibilities.

"This whole experience has made me want so much more for myself and my future. Unconditional love — there's nothing like it," she said. "I want to live up to my new family's picture of me and be a good sister for them and to be happy they found me."

Aubrey remained outwardly stoic and inwardly overwhelmed.

"I've never experienced such an outpouring of love," he said.

Inside, he was changing.

"Growing up, a bad day was always made so much worse because you think about how you're so terrible that someone gave you up," he said. "But now I have 16 brothers and sisters who love me. Someone can be crappy to me and it's OK because I have all those people behind me now."

Meredith held a party with almost the whole family. She gave Marilyn and Aubrey the crayon-written Valentine's cards they were supposed to get 16 years ago. People they had never seen spoke words that sounded familiar, yet unfamiliar.

"Sister." "Brother."

Column One: More great reads from the Los Angeles Times

In Ramona Gardens, simmering tensions ease

He's 63, she's 22 and the visa official is skeptical

Gunsmith has a full-bore interest and a high gauge of expertise

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.